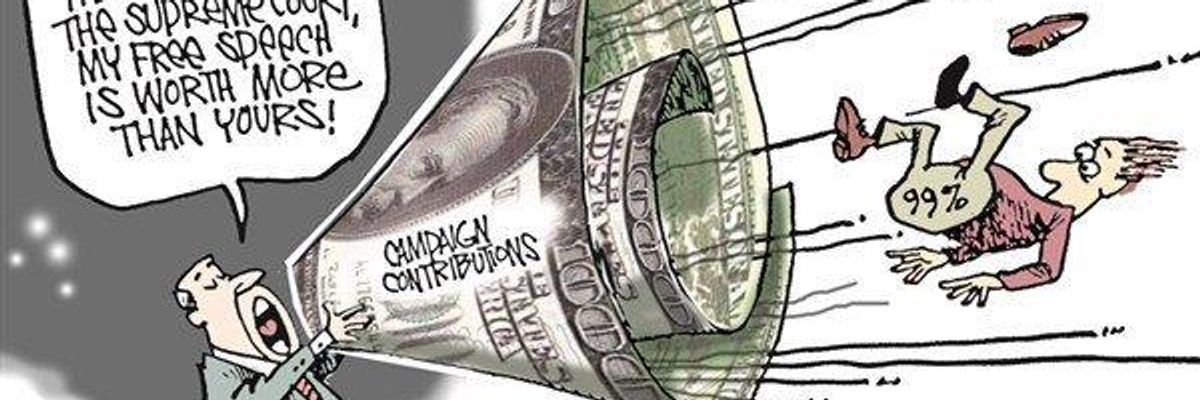

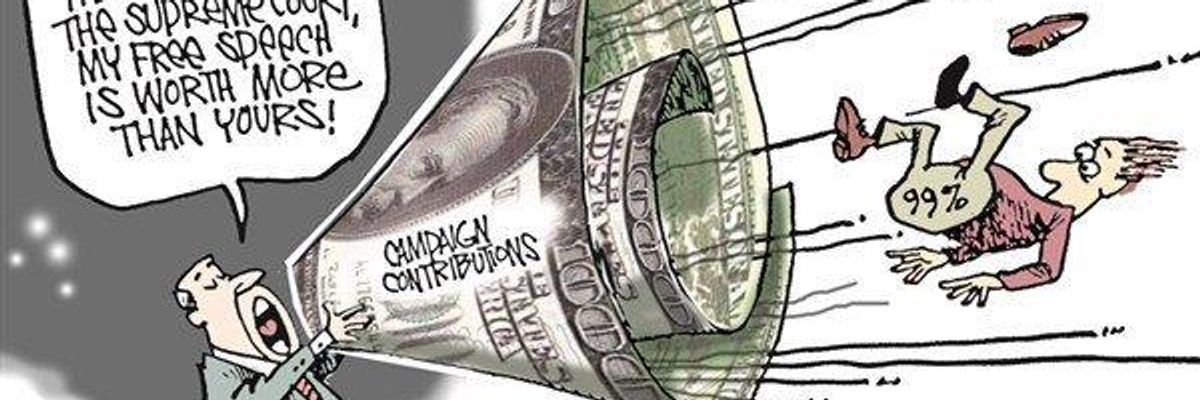

Free speech... if you can afford the megaphone! (Photo: Mike Keefe InToon.com)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Free speech... if you can afford the megaphone! (Photo: Mike Keefe InToon.com)

Americans may disagree about many things, but most of us come together in loathing the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United. We know it helped degrade our democracy as it opened the floodgates to independent, corporate campaign spending and enabled additional rulings that have led to Super PACs, along with ever-more "dark money."

Three-fourths of us want Citizens United overturned. I'm certainly one, and I'd long assumed I knew everything I needed to know about this unfortunate ruling. But I was in for a big surprise.

Buried in the 1976 Supreme Court decision that first equated political spending and speech, unleashing "big money" in politics--and cited one hundred times in Citizens United--is an argument against the Court's own findings, and one that crystalizes a key purpose of the First Amendment.

That opinion is Buckley v. Valeo.

In it, the Court makes clear, citing two earlier rulings, that the First Amendment's intent is not just to protect individuals against government control of speech. It is also to serve a vital public function: "to assure [the] unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of political and social changes desired by the people"; and "to secure 'the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources.'"

Yet, the Roberts Court has continued to betray this public function, as legal scholar Tim Kuhner makes clear in "The Market Metaphor, Radicalized." Reclaiming it begins with grasping the consequences of the Court's move to interpret free speech narrowly as an individual or group right to spend unlimited sums blasting viewpoints across the political airwaves.

One result is that little bandwidth remains for those without big bucks--thus, denying the First Amendment right, defined in Buckley, to free exchange of ideas using information from diverse and opposing sources in order to achieve the policies we citizens want. In stressing "interchange" and "diverse" sources, here the Court captures what I conceive as the essential "conversation of democracy." In it, as in all conversation, participants must not only be able to speak but also to be heard.

Sadly, however, in both Buckley and Citizens United the Court's decisions belie its own articulation of these precepts.

The Court argues in Buckley that capping individual or group political spending "necessarily reduces the quantity of expression by restricting the number of issues discussed, the depth of their exploration, and the size of the audience reached."

But, think for a moment, isn't the opposite true?

Take the "number of issues discussed."

In 2016, one-half of 1 percent of donors contributed two-thirds of funding in federal elections. With most campaign messaging financed by such a tiny minority, the "number of issues discussed" is likely to be more "restricted," not less, narrowed to matters this elite can leverage for political outcomes in its interest.

And as to the "depth" of issues' "exploration"?

In 2016, with money flooding the electoral process, campaigns spent almost $9.8 billion on advertising alone, shrinking complex issues to emotional sound bites. Shallowness, not "depth," is the result--especially in a campaign's final days when ads can become misleading or worse.

And the size of the "audience reached"?

Surely $9.8 billion can buy large audiences, but the term "audience" connotes one-way communication, not "interchange." Thus, we Americans end up with the right to speak but zero right to be heard.

I feel as if I'm invited to an auditorium for a political dialogue, but only a few of those assembled can afford pricey, electronic megaphones. Quickly I get it. Yes, I can speak, but only the handful with megaphones can be heard. Feeling useless and belittled, I head home.

Clearly, without both the right to speak and to be heard we cannot attain the "changes desired by the people," a goal of the First Amendment embedded in Buckley.

Yet, despite this huge, Court-imposed, boulder in the path of democracy, millions of citizens are uniting their voices to make themselves heard. Pursuing democracy-strengthening reforms--including victories in the 2018 midterms--they are building a political framework for robust "interchange" to realize "political and social changes desired by the people." In leading the charge on such reforms as fair voting districts and elections funded by the public and small-donors, citizens are fostering the essential conversation of democracy--one not drowned out by megaphones of great wealth.

Ironically, these engaged citizens are being faithful to our First Amendment rights as once spelled out in the Court's own logic.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Americans may disagree about many things, but most of us come together in loathing the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United. We know it helped degrade our democracy as it opened the floodgates to independent, corporate campaign spending and enabled additional rulings that have led to Super PACs, along with ever-more "dark money."

Three-fourths of us want Citizens United overturned. I'm certainly one, and I'd long assumed I knew everything I needed to know about this unfortunate ruling. But I was in for a big surprise.

Buried in the 1976 Supreme Court decision that first equated political spending and speech, unleashing "big money" in politics--and cited one hundred times in Citizens United--is an argument against the Court's own findings, and one that crystalizes a key purpose of the First Amendment.

That opinion is Buckley v. Valeo.

In it, the Court makes clear, citing two earlier rulings, that the First Amendment's intent is not just to protect individuals against government control of speech. It is also to serve a vital public function: "to assure [the] unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of political and social changes desired by the people"; and "to secure 'the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources.'"

Yet, the Roberts Court has continued to betray this public function, as legal scholar Tim Kuhner makes clear in "The Market Metaphor, Radicalized." Reclaiming it begins with grasping the consequences of the Court's move to interpret free speech narrowly as an individual or group right to spend unlimited sums blasting viewpoints across the political airwaves.

One result is that little bandwidth remains for those without big bucks--thus, denying the First Amendment right, defined in Buckley, to free exchange of ideas using information from diverse and opposing sources in order to achieve the policies we citizens want. In stressing "interchange" and "diverse" sources, here the Court captures what I conceive as the essential "conversation of democracy." In it, as in all conversation, participants must not only be able to speak but also to be heard.

Sadly, however, in both Buckley and Citizens United the Court's decisions belie its own articulation of these precepts.

The Court argues in Buckley that capping individual or group political spending "necessarily reduces the quantity of expression by restricting the number of issues discussed, the depth of their exploration, and the size of the audience reached."

But, think for a moment, isn't the opposite true?

Take the "number of issues discussed."

In 2016, one-half of 1 percent of donors contributed two-thirds of funding in federal elections. With most campaign messaging financed by such a tiny minority, the "number of issues discussed" is likely to be more "restricted," not less, narrowed to matters this elite can leverage for political outcomes in its interest.

And as to the "depth" of issues' "exploration"?

In 2016, with money flooding the electoral process, campaigns spent almost $9.8 billion on advertising alone, shrinking complex issues to emotional sound bites. Shallowness, not "depth," is the result--especially in a campaign's final days when ads can become misleading or worse.

And the size of the "audience reached"?

Surely $9.8 billion can buy large audiences, but the term "audience" connotes one-way communication, not "interchange." Thus, we Americans end up with the right to speak but zero right to be heard.

I feel as if I'm invited to an auditorium for a political dialogue, but only a few of those assembled can afford pricey, electronic megaphones. Quickly I get it. Yes, I can speak, but only the handful with megaphones can be heard. Feeling useless and belittled, I head home.

Clearly, without both the right to speak and to be heard we cannot attain the "changes desired by the people," a goal of the First Amendment embedded in Buckley.

Yet, despite this huge, Court-imposed, boulder in the path of democracy, millions of citizens are uniting their voices to make themselves heard. Pursuing democracy-strengthening reforms--including victories in the 2018 midterms--they are building a political framework for robust "interchange" to realize "political and social changes desired by the people." In leading the charge on such reforms as fair voting districts and elections funded by the public and small-donors, citizens are fostering the essential conversation of democracy--one not drowned out by megaphones of great wealth.

Ironically, these engaged citizens are being faithful to our First Amendment rights as once spelled out in the Court's own logic.

Americans may disagree about many things, but most of us come together in loathing the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United. We know it helped degrade our democracy as it opened the floodgates to independent, corporate campaign spending and enabled additional rulings that have led to Super PACs, along with ever-more "dark money."

Three-fourths of us want Citizens United overturned. I'm certainly one, and I'd long assumed I knew everything I needed to know about this unfortunate ruling. But I was in for a big surprise.

Buried in the 1976 Supreme Court decision that first equated political spending and speech, unleashing "big money" in politics--and cited one hundred times in Citizens United--is an argument against the Court's own findings, and one that crystalizes a key purpose of the First Amendment.

That opinion is Buckley v. Valeo.

In it, the Court makes clear, citing two earlier rulings, that the First Amendment's intent is not just to protect individuals against government control of speech. It is also to serve a vital public function: "to assure [the] unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of political and social changes desired by the people"; and "to secure 'the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources.'"

Yet, the Roberts Court has continued to betray this public function, as legal scholar Tim Kuhner makes clear in "The Market Metaphor, Radicalized." Reclaiming it begins with grasping the consequences of the Court's move to interpret free speech narrowly as an individual or group right to spend unlimited sums blasting viewpoints across the political airwaves.

One result is that little bandwidth remains for those without big bucks--thus, denying the First Amendment right, defined in Buckley, to free exchange of ideas using information from diverse and opposing sources in order to achieve the policies we citizens want. In stressing "interchange" and "diverse" sources, here the Court captures what I conceive as the essential "conversation of democracy." In it, as in all conversation, participants must not only be able to speak but also to be heard.

Sadly, however, in both Buckley and Citizens United the Court's decisions belie its own articulation of these precepts.

The Court argues in Buckley that capping individual or group political spending "necessarily reduces the quantity of expression by restricting the number of issues discussed, the depth of their exploration, and the size of the audience reached."

But, think for a moment, isn't the opposite true?

Take the "number of issues discussed."

In 2016, one-half of 1 percent of donors contributed two-thirds of funding in federal elections. With most campaign messaging financed by such a tiny minority, the "number of issues discussed" is likely to be more "restricted," not less, narrowed to matters this elite can leverage for political outcomes in its interest.

And as to the "depth" of issues' "exploration"?

In 2016, with money flooding the electoral process, campaigns spent almost $9.8 billion on advertising alone, shrinking complex issues to emotional sound bites. Shallowness, not "depth," is the result--especially in a campaign's final days when ads can become misleading or worse.

And the size of the "audience reached"?

Surely $9.8 billion can buy large audiences, but the term "audience" connotes one-way communication, not "interchange." Thus, we Americans end up with the right to speak but zero right to be heard.

I feel as if I'm invited to an auditorium for a political dialogue, but only a few of those assembled can afford pricey, electronic megaphones. Quickly I get it. Yes, I can speak, but only the handful with megaphones can be heard. Feeling useless and belittled, I head home.

Clearly, without both the right to speak and to be heard we cannot attain the "changes desired by the people," a goal of the First Amendment embedded in Buckley.

Yet, despite this huge, Court-imposed, boulder in the path of democracy, millions of citizens are uniting their voices to make themselves heard. Pursuing democracy-strengthening reforms--including victories in the 2018 midterms--they are building a political framework for robust "interchange" to realize "political and social changes desired by the people." In leading the charge on such reforms as fair voting districts and elections funded by the public and small-donors, citizens are fostering the essential conversation of democracy--one not drowned out by megaphones of great wealth.

Ironically, these engaged citizens are being faithful to our First Amendment rights as once spelled out in the Court's own logic.