Nationwide, the lowest-income households contribute, on average, 11 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the top 1 percent of households contribute just 7 percent of their income. (Photo: Timothy Krause/cc/flickr)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Nationwide, the lowest-income households contribute, on average, 11 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the top 1 percent of households contribute just 7 percent of their income. (Photo: Timothy Krause/cc/flickr)

The latest edition of ITEP's Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States details how most state and local tax structures contribute to income and wealth inequality by asking low- and moderate-income residents to pay a significantly higher effective tax rate than the wealthy.

Nationwide, the lowest-income households contribute, on average, 11 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the top 1 percent of households contribute just 7 percent of their income--that's a tax rate that is 50 percent higher for families working hard to make ends meet than for the wealthiest 1 percent. The tax systems of 45 states widen the income gap between their most affluent residents and lower- and middle-income families. State and local tax systems also worsen existing racial disparities.

Due to a long history of racially discriminatory economic and social policies and practices, communities of color, particularly Black and Latinx households, are overrepresented in the lowest-income quintiles of taxpayers and underrepresented in the highest. These policies include wealth stripping and exclusionary housing policies, a persistent reliance on regressive revenue streams like criminal justice fees and more. A 2019 ITEP analysis found that Black and Latinx households are overrepresented in the lowest-income quintiles; while they represent about 22 percent of overall tax returns, they account for 30 percent of the poorest quintile of taxpayers.

This means that regressive state and local tax codes are worsening both income inequalities and widening racial income and wealth gaps by requiring communities of color to contribute a larger share of their income in taxes.

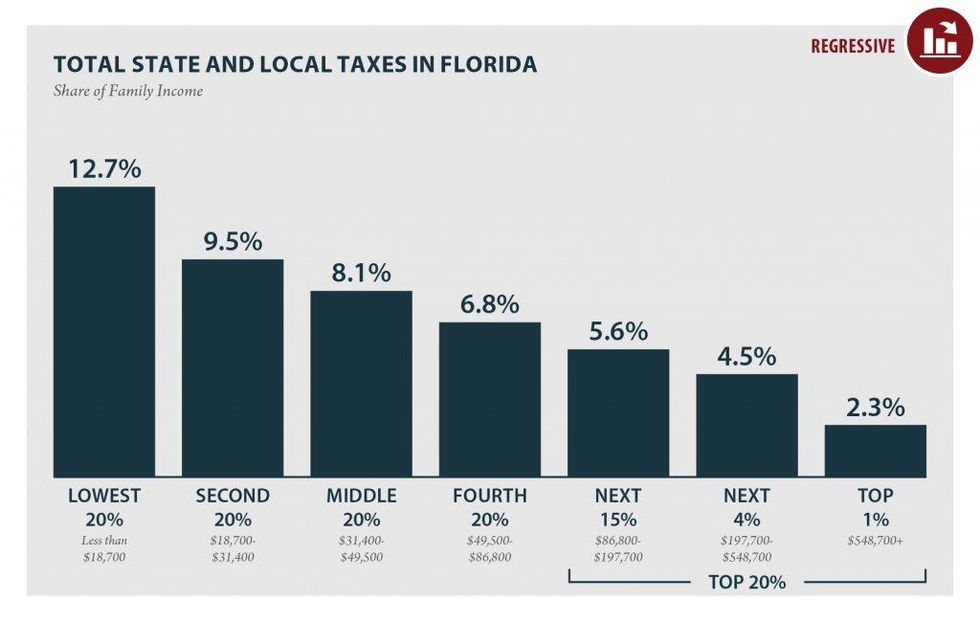

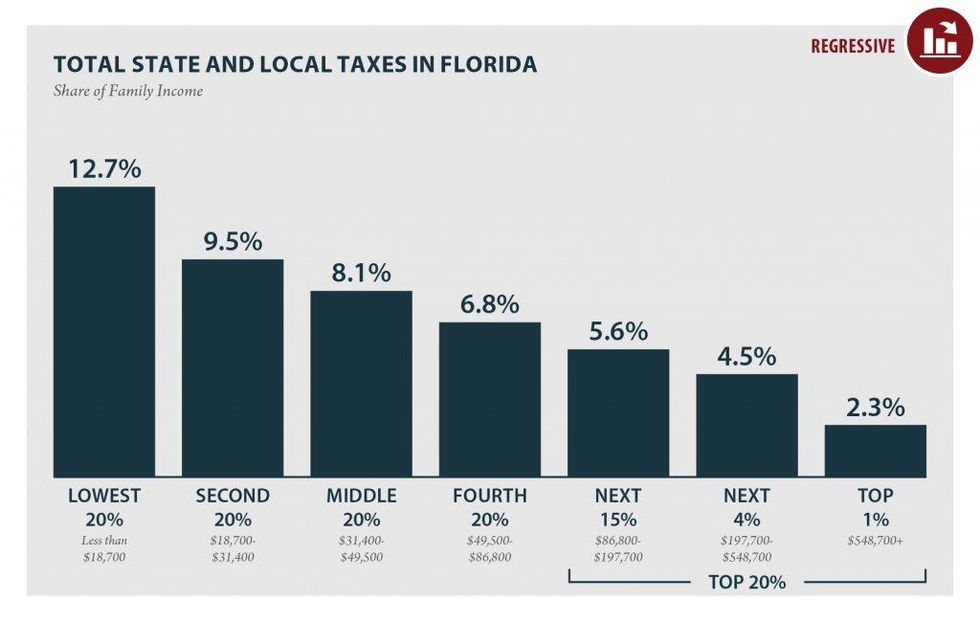

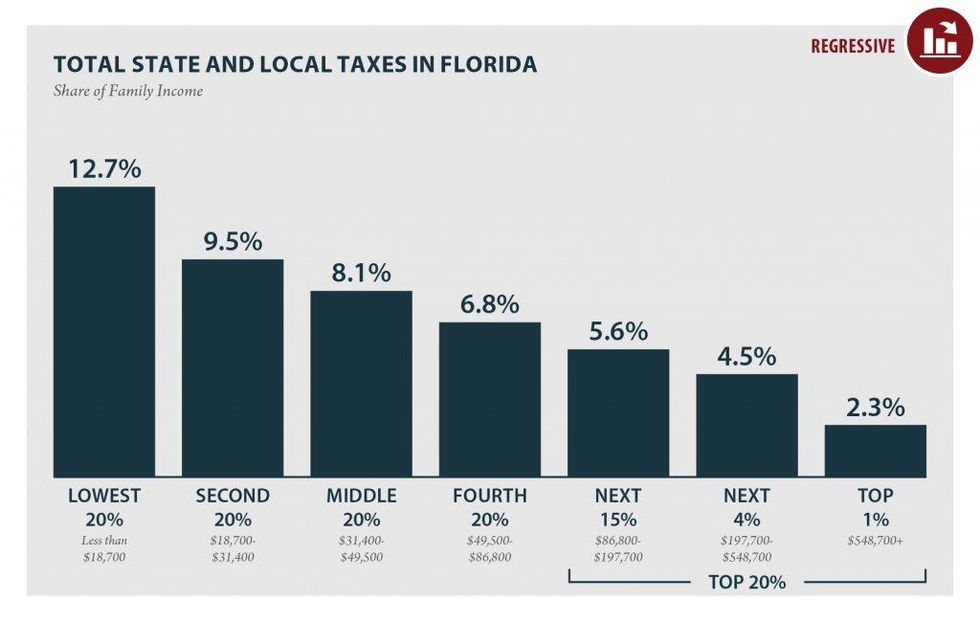

Take Florida as an example. The Sunshine State is often lauded as a "low-tax state" because of its lack of a personal income tax and low portion of taxes collected as a share of personal income. Although Florida ranks 50th nationally in taxes collected as a share of personal income, it is the ninth highest-tax state for low-income families. Florida ranks third in ITEP's Terrible 10 Most Regressive State and Local Tax Systems because of the disparity in taxes paid as a share of income by the wealthiest compared to low- and middle-income families. Floridians in the bottom quintile of taxpayers, with average incomes of just $12,500 annually, contribute nearly 13 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the wealthiest 1 percent, with average incomes of $2.3 million, contribute just 2 percent of their income in state and local taxes.

In California, while the effect of the racial income gap is still evident (white households are nine times more likely than Black households and seven times more likely than Latinx households to be among the wealthiest 1 percent of taxpayers) the state's more progressive tax code does less to worsen existing inequities. In California, the lowest-earning quintile, whose average income is about $14,300, contribute 10.5 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the wealthiest 1 percent contribute 12.4 percent of their income.

Black and Latinx households in the Golden State make up 4 and 28 percent of taxpaying households, respectively. Like Florida, Black and Latinx households in California are overrepresented in the poorest quintile--one-third of all Black and one-quarter of all Latinx taxpayers earn incomes less than $23,000. And like Florida, Black and Latinx households are underrepresented in the wealthiest top 1 percent of Californians at less than half a percent each. But unlike Florida, California's tax code slightly improves income inequality. The wealthiest 1 percent of Californians earning an average of $2.1 million annually pay a larger share of their income in taxes than those with the lowest incomes.

State tax codes can address income inequality and modestly remedy some of the economic inequities caused by a long history of social and economic policies that advantaged white communities and disadvantaged communities of color. But tax policy can only address a modicum of these broader social issues. Still, policymakers and citizens should work toward a system of taxation that does not worsen racial disparities.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

The latest edition of ITEP's Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States details how most state and local tax structures contribute to income and wealth inequality by asking low- and moderate-income residents to pay a significantly higher effective tax rate than the wealthy.

Nationwide, the lowest-income households contribute, on average, 11 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the top 1 percent of households contribute just 7 percent of their income--that's a tax rate that is 50 percent higher for families working hard to make ends meet than for the wealthiest 1 percent. The tax systems of 45 states widen the income gap between their most affluent residents and lower- and middle-income families. State and local tax systems also worsen existing racial disparities.

Due to a long history of racially discriminatory economic and social policies and practices, communities of color, particularly Black and Latinx households, are overrepresented in the lowest-income quintiles of taxpayers and underrepresented in the highest. These policies include wealth stripping and exclusionary housing policies, a persistent reliance on regressive revenue streams like criminal justice fees and more. A 2019 ITEP analysis found that Black and Latinx households are overrepresented in the lowest-income quintiles; while they represent about 22 percent of overall tax returns, they account for 30 percent of the poorest quintile of taxpayers.

This means that regressive state and local tax codes are worsening both income inequalities and widening racial income and wealth gaps by requiring communities of color to contribute a larger share of their income in taxes.

Take Florida as an example. The Sunshine State is often lauded as a "low-tax state" because of its lack of a personal income tax and low portion of taxes collected as a share of personal income. Although Florida ranks 50th nationally in taxes collected as a share of personal income, it is the ninth highest-tax state for low-income families. Florida ranks third in ITEP's Terrible 10 Most Regressive State and Local Tax Systems because of the disparity in taxes paid as a share of income by the wealthiest compared to low- and middle-income families. Floridians in the bottom quintile of taxpayers, with average incomes of just $12,500 annually, contribute nearly 13 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the wealthiest 1 percent, with average incomes of $2.3 million, contribute just 2 percent of their income in state and local taxes.

In California, while the effect of the racial income gap is still evident (white households are nine times more likely than Black households and seven times more likely than Latinx households to be among the wealthiest 1 percent of taxpayers) the state's more progressive tax code does less to worsen existing inequities. In California, the lowest-earning quintile, whose average income is about $14,300, contribute 10.5 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the wealthiest 1 percent contribute 12.4 percent of their income.

Black and Latinx households in the Golden State make up 4 and 28 percent of taxpaying households, respectively. Like Florida, Black and Latinx households in California are overrepresented in the poorest quintile--one-third of all Black and one-quarter of all Latinx taxpayers earn incomes less than $23,000. And like Florida, Black and Latinx households are underrepresented in the wealthiest top 1 percent of Californians at less than half a percent each. But unlike Florida, California's tax code slightly improves income inequality. The wealthiest 1 percent of Californians earning an average of $2.1 million annually pay a larger share of their income in taxes than those with the lowest incomes.

State tax codes can address income inequality and modestly remedy some of the economic inequities caused by a long history of social and economic policies that advantaged white communities and disadvantaged communities of color. But tax policy can only address a modicum of these broader social issues. Still, policymakers and citizens should work toward a system of taxation that does not worsen racial disparities.

The latest edition of ITEP's Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States details how most state and local tax structures contribute to income and wealth inequality by asking low- and moderate-income residents to pay a significantly higher effective tax rate than the wealthy.

Nationwide, the lowest-income households contribute, on average, 11 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the top 1 percent of households contribute just 7 percent of their income--that's a tax rate that is 50 percent higher for families working hard to make ends meet than for the wealthiest 1 percent. The tax systems of 45 states widen the income gap between their most affluent residents and lower- and middle-income families. State and local tax systems also worsen existing racial disparities.

Due to a long history of racially discriminatory economic and social policies and practices, communities of color, particularly Black and Latinx households, are overrepresented in the lowest-income quintiles of taxpayers and underrepresented in the highest. These policies include wealth stripping and exclusionary housing policies, a persistent reliance on regressive revenue streams like criminal justice fees and more. A 2019 ITEP analysis found that Black and Latinx households are overrepresented in the lowest-income quintiles; while they represent about 22 percent of overall tax returns, they account for 30 percent of the poorest quintile of taxpayers.

This means that regressive state and local tax codes are worsening both income inequalities and widening racial income and wealth gaps by requiring communities of color to contribute a larger share of their income in taxes.

Take Florida as an example. The Sunshine State is often lauded as a "low-tax state" because of its lack of a personal income tax and low portion of taxes collected as a share of personal income. Although Florida ranks 50th nationally in taxes collected as a share of personal income, it is the ninth highest-tax state for low-income families. Florida ranks third in ITEP's Terrible 10 Most Regressive State and Local Tax Systems because of the disparity in taxes paid as a share of income by the wealthiest compared to low- and middle-income families. Floridians in the bottom quintile of taxpayers, with average incomes of just $12,500 annually, contribute nearly 13 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the wealthiest 1 percent, with average incomes of $2.3 million, contribute just 2 percent of their income in state and local taxes.

In California, while the effect of the racial income gap is still evident (white households are nine times more likely than Black households and seven times more likely than Latinx households to be among the wealthiest 1 percent of taxpayers) the state's more progressive tax code does less to worsen existing inequities. In California, the lowest-earning quintile, whose average income is about $14,300, contribute 10.5 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the wealthiest 1 percent contribute 12.4 percent of their income.

Black and Latinx households in the Golden State make up 4 and 28 percent of taxpaying households, respectively. Like Florida, Black and Latinx households in California are overrepresented in the poorest quintile--one-third of all Black and one-quarter of all Latinx taxpayers earn incomes less than $23,000. And like Florida, Black and Latinx households are underrepresented in the wealthiest top 1 percent of Californians at less than half a percent each. But unlike Florida, California's tax code slightly improves income inequality. The wealthiest 1 percent of Californians earning an average of $2.1 million annually pay a larger share of their income in taxes than those with the lowest incomes.

State tax codes can address income inequality and modestly remedy some of the economic inequities caused by a long history of social and economic policies that advantaged white communities and disadvantaged communities of color. But tax policy can only address a modicum of these broader social issues. Still, policymakers and citizens should work toward a system of taxation that does not worsen racial disparities.