SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

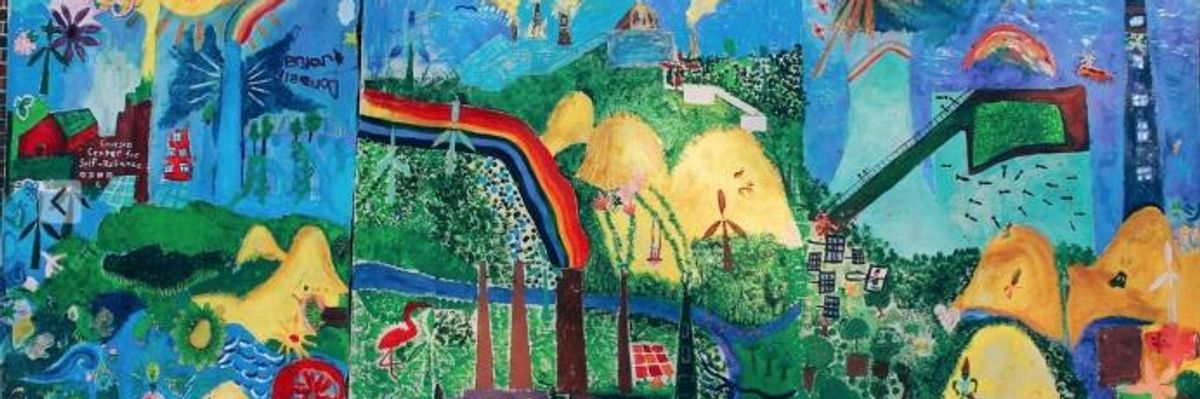

A mural from the "Ecopolis" project in Gary, Indiana. (Photo: Jeff Biggers)

We have a big job ahead of us. The perils of climate change will require that we craft new policies, fund robust scientific research and dramatically rethink most of the infrastructure we rely on -- everything from energy to food to transportation. Supporters of a Green New Deal have insisted that we need a World War II-scale mobilization to put the brakes on a fossil-fueled economy. All of this may conjure the work of engineers, urban planners, designers, scientists and policymakers.

But that's not all.

We'll also need more storytellers, says Jeff Biggers.

Biggers, a journalist, playwright and historian, has written hundreds of articles and eight books, including Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition and Reckoning at Eagle Creek: The Secret Legacy of Coal in the Heartland. He's spent decades deeply entrenched in movements for environmental protection and justice, but says he still felt we were falling short on inspiring the change needed to meet the scale of the problem.

So in 2014 he started the Climate Narrative Project, which works with high schools, universities and communities across the country to fuse science and art into new narratives about climate change and solutions that cut across disciplines and media.

We spoke with Biggers about his work helping to train climate storytellers and how it's changing communities.

What led you to start the Climate Narrative Project?

I feel like we have a climate communication crisis as much as a climate crisis. We're not just up against a formidable lobby of oil, gas and coal, but somehow we need to rise above the noise, the distractions and the globalization of indifference to injustice in daily life. While the majority of Americans recognize the growing problem of climate change, surveys have found that most people rarely discuss it or know how to engage in real action.

I'd seen this for years -- decades -- as a long-time organizer and environmental justice chronicler in coal country. We had often failed at communicating the right story to galvanize enough support to change destructive policies or hold outlaw coal companies and their bankrolled politicos accountable.

What do you hope the project will achieve?

Returning to my roots as a storyteller, I felt we needed to bring together science, humanities and the arts to come up with new climate narratives that could galvanize action and envision ways for regenerative solutions: in effect, to train a new generation of climate storytellers as community organizers.

Based in Iowa, I've worked with campuses, community groups and planners in towns and cities across the country, from Appalachia to the steel mills of Gary, Indiana, to rural Arizona to cities in Silicon Valley. I train with artists in all forms of storytelling -- dance, theatre, film, spoken word and creative writing, visual arts and radio -- in order to rethink our ways in regards to energy, food, waste, urban design and transportation, and our connection to our local history and nature. Then we envision a roadmap through stories in how we can transition toward creating carbon neutral regenerative cities and campuses -- ways in which we don't simply "do less harm," but actively repair the environmental destruction and replenish our natural resources.

What has been one of your favorite stories that have been told through the project?

In one of my Climate Narrative Project cadres an art student in Iowa stunned her audience by displaying a beautiful painting she had done of the prairies, spoke about her interviews at Standing Rock and then poured black oil all over it to demonstrate the impact of pipeline bursts.

What kind of effects have you seen on audiences or in the communities where these projects have been created?

On a community level, I was blown away by the "Ecopolis" stories composed by a group of urban farmers, rappers, educators, jazz musicians and artists in Gary, Indiana, who brought together an unusually diverse coalition -- mainstream environmental groups, churches, teachers and students, business people, city administrators -- with their vision of the famous steel city as a carbon neutral regenerative city, walking us through a decade of transitions to green-enterprise zones and circular economies, soil mitigation and local food, rewilding and reconnecting to the extraordinary and biodiverse Indiana dunes.

After the multimedia theatre event at a solar-powered church, the local groups sat down for a lunch hosted by urban farmers and began the process of making this vision a reality.

On a campus level, I've been amazed by the Climate Stories Collaborative at Appalachian State University, which followed up our Climate Narrative Project training as an initiative to bring together 23 different academic units and departments to engage students and faculty with story-driven climate actions.

As climate impacts increase and this issue hits home for more and more people, do you think art and culture will play a bigger role in how we understand the problem and craft the solutions we want to see?

If we're serious about engaging communities for climate action and environmental justice, storytelling and all the arts must play a key role in our initiatives. I tell every organization, community and interfaith group, school and university, and especially town and city councils: Don't waste your resources on bureaucrats, task forces and commissioning studies that no one reads -- invest in the arts, storytellers, writers, playwrights and farmers.

Every organization, campus and city should have a Climate Storyteller-in-Residence, a Climate Artist-in-Residence, a Farmer-in-Residence, etc. If we are to meet the urgency of climate action, we must be training brigades of climate storytellers to astonish, inspire and organize our communities.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

We have a big job ahead of us. The perils of climate change will require that we craft new policies, fund robust scientific research and dramatically rethink most of the infrastructure we rely on -- everything from energy to food to transportation. Supporters of a Green New Deal have insisted that we need a World War II-scale mobilization to put the brakes on a fossil-fueled economy. All of this may conjure the work of engineers, urban planners, designers, scientists and policymakers.

But that's not all.

We'll also need more storytellers, says Jeff Biggers.

Biggers, a journalist, playwright and historian, has written hundreds of articles and eight books, including Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition and Reckoning at Eagle Creek: The Secret Legacy of Coal in the Heartland. He's spent decades deeply entrenched in movements for environmental protection and justice, but says he still felt we were falling short on inspiring the change needed to meet the scale of the problem.

So in 2014 he started the Climate Narrative Project, which works with high schools, universities and communities across the country to fuse science and art into new narratives about climate change and solutions that cut across disciplines and media.

We spoke with Biggers about his work helping to train climate storytellers and how it's changing communities.

What led you to start the Climate Narrative Project?

I feel like we have a climate communication crisis as much as a climate crisis. We're not just up against a formidable lobby of oil, gas and coal, but somehow we need to rise above the noise, the distractions and the globalization of indifference to injustice in daily life. While the majority of Americans recognize the growing problem of climate change, surveys have found that most people rarely discuss it or know how to engage in real action.

I'd seen this for years -- decades -- as a long-time organizer and environmental justice chronicler in coal country. We had often failed at communicating the right story to galvanize enough support to change destructive policies or hold outlaw coal companies and their bankrolled politicos accountable.

What do you hope the project will achieve?

Returning to my roots as a storyteller, I felt we needed to bring together science, humanities and the arts to come up with new climate narratives that could galvanize action and envision ways for regenerative solutions: in effect, to train a new generation of climate storytellers as community organizers.

Based in Iowa, I've worked with campuses, community groups and planners in towns and cities across the country, from Appalachia to the steel mills of Gary, Indiana, to rural Arizona to cities in Silicon Valley. I train with artists in all forms of storytelling -- dance, theatre, film, spoken word and creative writing, visual arts and radio -- in order to rethink our ways in regards to energy, food, waste, urban design and transportation, and our connection to our local history and nature. Then we envision a roadmap through stories in how we can transition toward creating carbon neutral regenerative cities and campuses -- ways in which we don't simply "do less harm," but actively repair the environmental destruction and replenish our natural resources.

What has been one of your favorite stories that have been told through the project?

In one of my Climate Narrative Project cadres an art student in Iowa stunned her audience by displaying a beautiful painting she had done of the prairies, spoke about her interviews at Standing Rock and then poured black oil all over it to demonstrate the impact of pipeline bursts.

What kind of effects have you seen on audiences or in the communities where these projects have been created?

On a community level, I was blown away by the "Ecopolis" stories composed by a group of urban farmers, rappers, educators, jazz musicians and artists in Gary, Indiana, who brought together an unusually diverse coalition -- mainstream environmental groups, churches, teachers and students, business people, city administrators -- with their vision of the famous steel city as a carbon neutral regenerative city, walking us through a decade of transitions to green-enterprise zones and circular economies, soil mitigation and local food, rewilding and reconnecting to the extraordinary and biodiverse Indiana dunes.

After the multimedia theatre event at a solar-powered church, the local groups sat down for a lunch hosted by urban farmers and began the process of making this vision a reality.

On a campus level, I've been amazed by the Climate Stories Collaborative at Appalachian State University, which followed up our Climate Narrative Project training as an initiative to bring together 23 different academic units and departments to engage students and faculty with story-driven climate actions.

As climate impacts increase and this issue hits home for more and more people, do you think art and culture will play a bigger role in how we understand the problem and craft the solutions we want to see?

If we're serious about engaging communities for climate action and environmental justice, storytelling and all the arts must play a key role in our initiatives. I tell every organization, community and interfaith group, school and university, and especially town and city councils: Don't waste your resources on bureaucrats, task forces and commissioning studies that no one reads -- invest in the arts, storytellers, writers, playwrights and farmers.

Every organization, campus and city should have a Climate Storyteller-in-Residence, a Climate Artist-in-Residence, a Farmer-in-Residence, etc. If we are to meet the urgency of climate action, we must be training brigades of climate storytellers to astonish, inspire and organize our communities.

We have a big job ahead of us. The perils of climate change will require that we craft new policies, fund robust scientific research and dramatically rethink most of the infrastructure we rely on -- everything from energy to food to transportation. Supporters of a Green New Deal have insisted that we need a World War II-scale mobilization to put the brakes on a fossil-fueled economy. All of this may conjure the work of engineers, urban planners, designers, scientists and policymakers.

But that's not all.

We'll also need more storytellers, says Jeff Biggers.

Biggers, a journalist, playwright and historian, has written hundreds of articles and eight books, including Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition and Reckoning at Eagle Creek: The Secret Legacy of Coal in the Heartland. He's spent decades deeply entrenched in movements for environmental protection and justice, but says he still felt we were falling short on inspiring the change needed to meet the scale of the problem.

So in 2014 he started the Climate Narrative Project, which works with high schools, universities and communities across the country to fuse science and art into new narratives about climate change and solutions that cut across disciplines and media.

We spoke with Biggers about his work helping to train climate storytellers and how it's changing communities.

What led you to start the Climate Narrative Project?

I feel like we have a climate communication crisis as much as a climate crisis. We're not just up against a formidable lobby of oil, gas and coal, but somehow we need to rise above the noise, the distractions and the globalization of indifference to injustice in daily life. While the majority of Americans recognize the growing problem of climate change, surveys have found that most people rarely discuss it or know how to engage in real action.

I'd seen this for years -- decades -- as a long-time organizer and environmental justice chronicler in coal country. We had often failed at communicating the right story to galvanize enough support to change destructive policies or hold outlaw coal companies and their bankrolled politicos accountable.

What do you hope the project will achieve?

Returning to my roots as a storyteller, I felt we needed to bring together science, humanities and the arts to come up with new climate narratives that could galvanize action and envision ways for regenerative solutions: in effect, to train a new generation of climate storytellers as community organizers.

Based in Iowa, I've worked with campuses, community groups and planners in towns and cities across the country, from Appalachia to the steel mills of Gary, Indiana, to rural Arizona to cities in Silicon Valley. I train with artists in all forms of storytelling -- dance, theatre, film, spoken word and creative writing, visual arts and radio -- in order to rethink our ways in regards to energy, food, waste, urban design and transportation, and our connection to our local history and nature. Then we envision a roadmap through stories in how we can transition toward creating carbon neutral regenerative cities and campuses -- ways in which we don't simply "do less harm," but actively repair the environmental destruction and replenish our natural resources.

What has been one of your favorite stories that have been told through the project?

In one of my Climate Narrative Project cadres an art student in Iowa stunned her audience by displaying a beautiful painting she had done of the prairies, spoke about her interviews at Standing Rock and then poured black oil all over it to demonstrate the impact of pipeline bursts.

What kind of effects have you seen on audiences or in the communities where these projects have been created?

On a community level, I was blown away by the "Ecopolis" stories composed by a group of urban farmers, rappers, educators, jazz musicians and artists in Gary, Indiana, who brought together an unusually diverse coalition -- mainstream environmental groups, churches, teachers and students, business people, city administrators -- with their vision of the famous steel city as a carbon neutral regenerative city, walking us through a decade of transitions to green-enterprise zones and circular economies, soil mitigation and local food, rewilding and reconnecting to the extraordinary and biodiverse Indiana dunes.

After the multimedia theatre event at a solar-powered church, the local groups sat down for a lunch hosted by urban farmers and began the process of making this vision a reality.

On a campus level, I've been amazed by the Climate Stories Collaborative at Appalachian State University, which followed up our Climate Narrative Project training as an initiative to bring together 23 different academic units and departments to engage students and faculty with story-driven climate actions.

As climate impacts increase and this issue hits home for more and more people, do you think art and culture will play a bigger role in how we understand the problem and craft the solutions we want to see?

If we're serious about engaging communities for climate action and environmental justice, storytelling and all the arts must play a key role in our initiatives. I tell every organization, community and interfaith group, school and university, and especially town and city councils: Don't waste your resources on bureaucrats, task forces and commissioning studies that no one reads -- invest in the arts, storytellers, writers, playwrights and farmers.

Every organization, campus and city should have a Climate Storyteller-in-Residence, a Climate Artist-in-Residence, a Farmer-in-Residence, etc. If we are to meet the urgency of climate action, we must be training brigades of climate storytellers to astonish, inspire and organize our communities.