SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

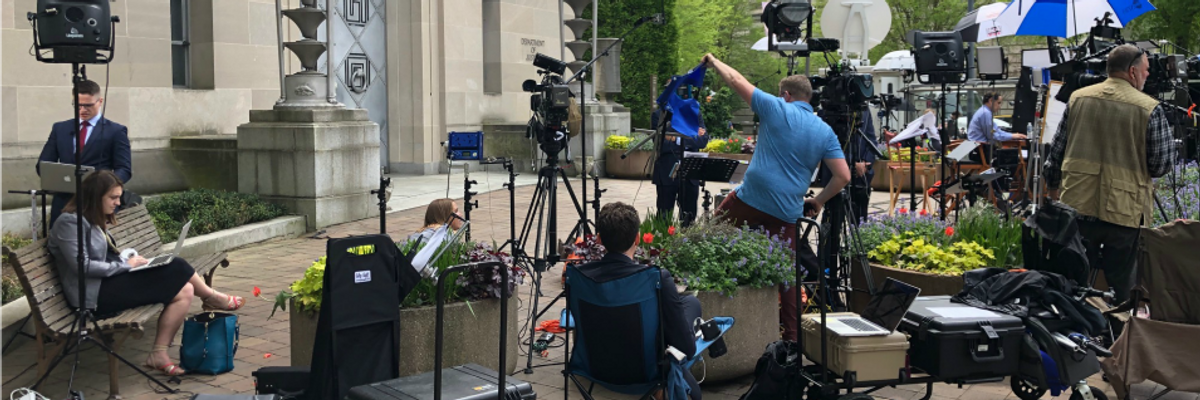

Journalists and media team members gathered outside the Department of Justice building in Washington, DC on April 18, 2019 in the wake of the release of Special Counsel Robert Mueller's redacted report. (Photo: Common Dreams/CC-BY-ND 3.0)

Even in its redacted form, and even without the counterintelligence investigation material that was part of its task, the Mueller Report has largely vindicated the last three years of media coverage of Donald Trump's and his presidential campaign's connections to Russia.

The report doesn't contain much material that was not previously reported, at least fragmentarily, in the mainstream press. But it compiles it in one place, adds technical information otherwise unknowable (like the type of malware used to compress and transmit the DNC files - the press obviously can't call the National Security Agency for details on that), and it corroborates previous reporting by examining witnesses (the media plainly cannot compel testimony under oath).

This is not to say the press did not make mistakes along the way (some of them serious), and I certainly do not mean to whitewash the deep and chronic problems of the media. The consolidation of news reporting into a relative handful of corporate-controlled entities is a real concern, as are the evisceration of newsrooms and the disappearance of overseas bureaus. Perhaps even more problematic is the lack of a stable, moneymaking business model for serious, for-profit news organizations.

They also have fallen into the cringe-worthy habit of running the publicity stunts of entertainers and attention-seekers under the rubric of legitimate news. Breathless reportage of the musings of bogus celebrities as if they were the observations of Nobel laureates is particularly cloying. It was this juvenile tendency that impelled the media to give so much free airtime during the campaign to Trump's evil-clown act.

The media's mistakes in its coverage of Trump and Russiagate mostly have been errors of omission rather than factually inaccurate reporting. The sheer scale of Trump's malice and the consistent bad faith of his Republican defenders are so unprecedented and baffling that journalists understandably were afraid of drawing the proper conclusions from the evidence before them.

As I have written before, decades of being told that they are bicoastal elitists, viciously biased against Republicans and out of touch with "real" Americans, has conditioned some in the press to subconsciously accept the accusation.

This has led to embarrassingly cliched reportage in the Trump era, such as the media's periodic anthropological tours of the Heartland, replete with salt-of-the-earth stereotypes who supposedly gave Trump their vote as a roll of the dice to improve their economic plight. But while "economic anxiety" may have been partly true as an inducement, more empirical research has concluded that there were far darker motives in play than just steady, good-paying employment.

Likewise, their obsession with "balance" at all costs has occasionally led the media to bend over backwards to accommodate views which have no place in the news room, such as CNN's hiring of Corey Lewandowski.

Just now, CNN has opened its online opinion column to Scott Jennings, a campaign hack for Mitch McConnell, to claim that the Mueller Report "proves" Russian election disruption was all Barack Obama's fault. Left unmentioned was the fact that Jennings's boss, the Senate majority leader, reacted angrily when Obama administration intelligence officials sought bipartisan congressional action against the Russian interference. McConnell tried to blackmail them by threatening to turn the issue into a partisan mud-slinging match. CNN's editors were either woefully ignorant of the backstory, or didn't care.

Bound up with the press' reluctance to accept the truth before them was their tardiness during the 2016 campaign to recognize Trump for the threat he was, rather than merely being a harmless jackass who would surely lose.

In October 2016, after having become the recipient of literature from a pro-Trump propaganda campaign run by an extreme-right group in Germany that had hallmarks of Russian control, my curiosity was piqued. I phoned the New York Times to ask whether they were investigating such foreign-based disinformation that might be connected with the presidential campaign. David Sanger, their chief Washington correspondent and resident foreign policy guru, was arrogantly dismissive, insisting that "we" know everything worth knowing about any putative Russian disruption operations. He ultimately fobbed me off to the Times' Berlin bureau, which called me back after a couple of days and demonstrated its cluelessness about and lack of interest in a propaganda campaign being run out of the same city in which the bureau was located.

The denouement to my unproductive encounter with the pompous Mr. Sanger and his associates was probably the media's greatest mistake in reporting Russiagate, because it was the most consequential. Barely a week later, the Times led with a story reporting that the FBI had all but absolved the Trump campaign of collusion with Russia, including the gratuitous opinion that the Russian hacking was not even directed at electing Trump. In reality, the FBI drew no such conclusions, but coming just eight days before the election, it was life-saving wind in the Republican candidate's sails.

With Trump's election the media finally began to take Trump seriously, and its reporting improved in proportion. Michael Flynn's shenanigans during the transition, and the administration's bizarre behavior the very day of the inauguration (when it claimed in the face of clear visual evidence that the crowds on the Mall exceeded those of Obama's swearing-in of 2009) may have been the jolt to compel the press to do its job.

The scales of justice may swing this way and that, but one trusts they will ultimately balance, not from some naive faith in humanity, but rather from the suspicion that the truth will out, however tortuous the path: because those who know cannot keep silent over the long term. A free and independent press, which generations before us have struggled for, is essential to securing that truth.

The mainstream media, like the weather, is something everybody has something to complain about. But it is an indispensible adjunct to any government that adheres to the rule of law. For as James Madison said, "A popular government without popular information or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce, or a tragedy, or perhaps both."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Even in its redacted form, and even without the counterintelligence investigation material that was part of its task, the Mueller Report has largely vindicated the last three years of media coverage of Donald Trump's and his presidential campaign's connections to Russia.

The report doesn't contain much material that was not previously reported, at least fragmentarily, in the mainstream press. But it compiles it in one place, adds technical information otherwise unknowable (like the type of malware used to compress and transmit the DNC files - the press obviously can't call the National Security Agency for details on that), and it corroborates previous reporting by examining witnesses (the media plainly cannot compel testimony under oath).

This is not to say the press did not make mistakes along the way (some of them serious), and I certainly do not mean to whitewash the deep and chronic problems of the media. The consolidation of news reporting into a relative handful of corporate-controlled entities is a real concern, as are the evisceration of newsrooms and the disappearance of overseas bureaus. Perhaps even more problematic is the lack of a stable, moneymaking business model for serious, for-profit news organizations.

They also have fallen into the cringe-worthy habit of running the publicity stunts of entertainers and attention-seekers under the rubric of legitimate news. Breathless reportage of the musings of bogus celebrities as if they were the observations of Nobel laureates is particularly cloying. It was this juvenile tendency that impelled the media to give so much free airtime during the campaign to Trump's evil-clown act.

The media's mistakes in its coverage of Trump and Russiagate mostly have been errors of omission rather than factually inaccurate reporting. The sheer scale of Trump's malice and the consistent bad faith of his Republican defenders are so unprecedented and baffling that journalists understandably were afraid of drawing the proper conclusions from the evidence before them.

As I have written before, decades of being told that they are bicoastal elitists, viciously biased against Republicans and out of touch with "real" Americans, has conditioned some in the press to subconsciously accept the accusation.

This has led to embarrassingly cliched reportage in the Trump era, such as the media's periodic anthropological tours of the Heartland, replete with salt-of-the-earth stereotypes who supposedly gave Trump their vote as a roll of the dice to improve their economic plight. But while "economic anxiety" may have been partly true as an inducement, more empirical research has concluded that there were far darker motives in play than just steady, good-paying employment.

Likewise, their obsession with "balance" at all costs has occasionally led the media to bend over backwards to accommodate views which have no place in the news room, such as CNN's hiring of Corey Lewandowski.

Just now, CNN has opened its online opinion column to Scott Jennings, a campaign hack for Mitch McConnell, to claim that the Mueller Report "proves" Russian election disruption was all Barack Obama's fault. Left unmentioned was the fact that Jennings's boss, the Senate majority leader, reacted angrily when Obama administration intelligence officials sought bipartisan congressional action against the Russian interference. McConnell tried to blackmail them by threatening to turn the issue into a partisan mud-slinging match. CNN's editors were either woefully ignorant of the backstory, or didn't care.

Bound up with the press' reluctance to accept the truth before them was their tardiness during the 2016 campaign to recognize Trump for the threat he was, rather than merely being a harmless jackass who would surely lose.

In October 2016, after having become the recipient of literature from a pro-Trump propaganda campaign run by an extreme-right group in Germany that had hallmarks of Russian control, my curiosity was piqued. I phoned the New York Times to ask whether they were investigating such foreign-based disinformation that might be connected with the presidential campaign. David Sanger, their chief Washington correspondent and resident foreign policy guru, was arrogantly dismissive, insisting that "we" know everything worth knowing about any putative Russian disruption operations. He ultimately fobbed me off to the Times' Berlin bureau, which called me back after a couple of days and demonstrated its cluelessness about and lack of interest in a propaganda campaign being run out of the same city in which the bureau was located.

The denouement to my unproductive encounter with the pompous Mr. Sanger and his associates was probably the media's greatest mistake in reporting Russiagate, because it was the most consequential. Barely a week later, the Times led with a story reporting that the FBI had all but absolved the Trump campaign of collusion with Russia, including the gratuitous opinion that the Russian hacking was not even directed at electing Trump. In reality, the FBI drew no such conclusions, but coming just eight days before the election, it was life-saving wind in the Republican candidate's sails.

With Trump's election the media finally began to take Trump seriously, and its reporting improved in proportion. Michael Flynn's shenanigans during the transition, and the administration's bizarre behavior the very day of the inauguration (when it claimed in the face of clear visual evidence that the crowds on the Mall exceeded those of Obama's swearing-in of 2009) may have been the jolt to compel the press to do its job.

The scales of justice may swing this way and that, but one trusts they will ultimately balance, not from some naive faith in humanity, but rather from the suspicion that the truth will out, however tortuous the path: because those who know cannot keep silent over the long term. A free and independent press, which generations before us have struggled for, is essential to securing that truth.

The mainstream media, like the weather, is something everybody has something to complain about. But it is an indispensible adjunct to any government that adheres to the rule of law. For as James Madison said, "A popular government without popular information or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce, or a tragedy, or perhaps both."

Even in its redacted form, and even without the counterintelligence investigation material that was part of its task, the Mueller Report has largely vindicated the last three years of media coverage of Donald Trump's and his presidential campaign's connections to Russia.

The report doesn't contain much material that was not previously reported, at least fragmentarily, in the mainstream press. But it compiles it in one place, adds technical information otherwise unknowable (like the type of malware used to compress and transmit the DNC files - the press obviously can't call the National Security Agency for details on that), and it corroborates previous reporting by examining witnesses (the media plainly cannot compel testimony under oath).

This is not to say the press did not make mistakes along the way (some of them serious), and I certainly do not mean to whitewash the deep and chronic problems of the media. The consolidation of news reporting into a relative handful of corporate-controlled entities is a real concern, as are the evisceration of newsrooms and the disappearance of overseas bureaus. Perhaps even more problematic is the lack of a stable, moneymaking business model for serious, for-profit news organizations.

They also have fallen into the cringe-worthy habit of running the publicity stunts of entertainers and attention-seekers under the rubric of legitimate news. Breathless reportage of the musings of bogus celebrities as if they were the observations of Nobel laureates is particularly cloying. It was this juvenile tendency that impelled the media to give so much free airtime during the campaign to Trump's evil-clown act.

The media's mistakes in its coverage of Trump and Russiagate mostly have been errors of omission rather than factually inaccurate reporting. The sheer scale of Trump's malice and the consistent bad faith of his Republican defenders are so unprecedented and baffling that journalists understandably were afraid of drawing the proper conclusions from the evidence before them.

As I have written before, decades of being told that they are bicoastal elitists, viciously biased against Republicans and out of touch with "real" Americans, has conditioned some in the press to subconsciously accept the accusation.

This has led to embarrassingly cliched reportage in the Trump era, such as the media's periodic anthropological tours of the Heartland, replete with salt-of-the-earth stereotypes who supposedly gave Trump their vote as a roll of the dice to improve their economic plight. But while "economic anxiety" may have been partly true as an inducement, more empirical research has concluded that there were far darker motives in play than just steady, good-paying employment.

Likewise, their obsession with "balance" at all costs has occasionally led the media to bend over backwards to accommodate views which have no place in the news room, such as CNN's hiring of Corey Lewandowski.

Just now, CNN has opened its online opinion column to Scott Jennings, a campaign hack for Mitch McConnell, to claim that the Mueller Report "proves" Russian election disruption was all Barack Obama's fault. Left unmentioned was the fact that Jennings's boss, the Senate majority leader, reacted angrily when Obama administration intelligence officials sought bipartisan congressional action against the Russian interference. McConnell tried to blackmail them by threatening to turn the issue into a partisan mud-slinging match. CNN's editors were either woefully ignorant of the backstory, or didn't care.

Bound up with the press' reluctance to accept the truth before them was their tardiness during the 2016 campaign to recognize Trump for the threat he was, rather than merely being a harmless jackass who would surely lose.

In October 2016, after having become the recipient of literature from a pro-Trump propaganda campaign run by an extreme-right group in Germany that had hallmarks of Russian control, my curiosity was piqued. I phoned the New York Times to ask whether they were investigating such foreign-based disinformation that might be connected with the presidential campaign. David Sanger, their chief Washington correspondent and resident foreign policy guru, was arrogantly dismissive, insisting that "we" know everything worth knowing about any putative Russian disruption operations. He ultimately fobbed me off to the Times' Berlin bureau, which called me back after a couple of days and demonstrated its cluelessness about and lack of interest in a propaganda campaign being run out of the same city in which the bureau was located.

The denouement to my unproductive encounter with the pompous Mr. Sanger and his associates was probably the media's greatest mistake in reporting Russiagate, because it was the most consequential. Barely a week later, the Times led with a story reporting that the FBI had all but absolved the Trump campaign of collusion with Russia, including the gratuitous opinion that the Russian hacking was not even directed at electing Trump. In reality, the FBI drew no such conclusions, but coming just eight days before the election, it was life-saving wind in the Republican candidate's sails.

With Trump's election the media finally began to take Trump seriously, and its reporting improved in proportion. Michael Flynn's shenanigans during the transition, and the administration's bizarre behavior the very day of the inauguration (when it claimed in the face of clear visual evidence that the crowds on the Mall exceeded those of Obama's swearing-in of 2009) may have been the jolt to compel the press to do its job.

The scales of justice may swing this way and that, but one trusts they will ultimately balance, not from some naive faith in humanity, but rather from the suspicion that the truth will out, however tortuous the path: because those who know cannot keep silent over the long term. A free and independent press, which generations before us have struggled for, is essential to securing that truth.

The mainstream media, like the weather, is something everybody has something to complain about. But it is an indispensible adjunct to any government that adheres to the rule of law. For as James Madison said, "A popular government without popular information or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce, or a tragedy, or perhaps both."