SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

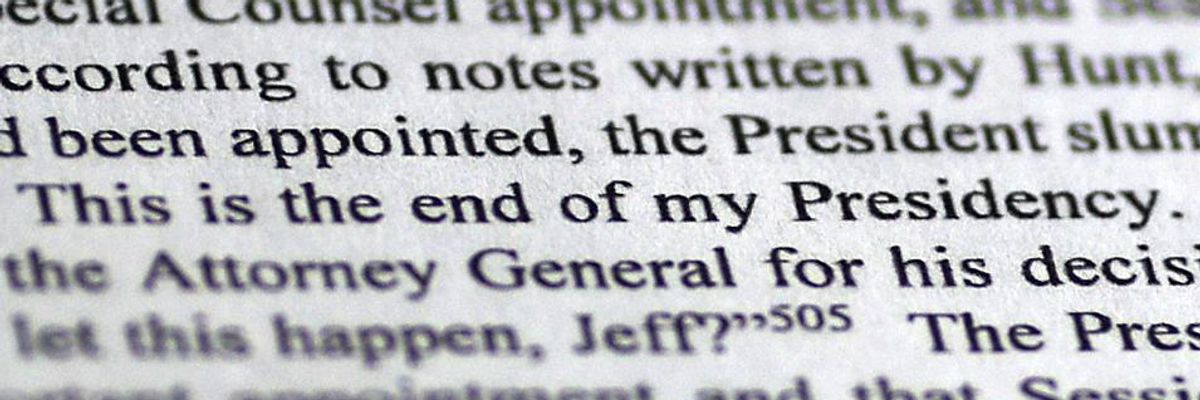

A page from the recently released Mueller Report is shown April 18, 2019 in Washington, DC. According to a person interviewed by Mueller's team, in response to news from then Attorney General Jeff Sessions that Robert Mueller had been appointed as a Special Counsel to investigate allegations of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, U.S. President Donald Trump said 'Oh my God. This is terrible. This is the end of my presidency.' (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

Special Counsel Robert Mueller's long-awaited report, released to the public in a redacted version on April 18, lays out in meticulous detail both a blatantly illegal effort by Russia to throw the 2016 presidential election to Donald Trump and repeated efforts by President Trump to end, limit, or impede Mueller's investigation of Russian interference. Trump's efforts included firing or attempting to fire those overseeing the investigation, directing subordinates to lie on his behalf, cajoling witnesses not to cooperate, and doctoring a public statement about a Trump Tower meeting between his son and closest advisers and a Russian lawyer offering compromising information on Hillary Clinton.

Attorney General William Barr, who has shown himself to be exactly the kind of presidential protector Trump wanted Jeff Sessions to be, did his best to whitewash the report. Almost four weeks before it was released to the public, Barr wrote a four-page letter to Congress purporting to summarize its findings. But as The New York Times's Charlie Savage has shown, in the letter Barr took Mueller's words out of context and omitted all mention of the damning evidence that courses through the report.* Just before releasing the report to the public, Barr also held a press conference in which he again distorted its conclusions, stating that it found no collusion with the Russians and no obstruction of justice by the president. Both statements are profoundly misleading.

"If this was a witch hunt, it found a lot of witches."

The Mueller report (pdf) did not address "collusion," a term that has no legal definition, but the narrower question of criminal conspiracy. It found no evidence that Trump campaign officials conspired with the Russians' disinformation campaigns or hacking of computers belonging to the Democratic National Committee and the Clinton campaign. But it describes extensive contacts between the Trump campaign and the Russians, many of which Trump campaign officials lied about. And it finds substantial evidence both "that the Russian government perceived it would benefit from a Trump presidency and worked to secure that outcome, and that the Campaign expected it would benefit electorally from information stolen and released through Russian efforts." Russian intelligence agency hackers targeted Hillary Clinton's home office within five hours of Trump's public request in July 2016 that the Russians find her deleted e-mails. And WikiLeaks, which was in close touch with Trump advisers, began releasing its trove of e-mails stolen by the Russians from Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta one hour after the Access Hollywood tape in which Trump bragged about assaulting women was made public in October 2016.

Trump has repeatedly dismissed the investigation as a "witch hunt." But Mueller found "sweeping and systematic" intrusions by Russia in the presidential campaign, all aimed at supporting Trump's election. He and his team indicted twenty-five Russians and secured the convictions or guilty pleas of several Trump campaign officials for lying in connection with the investigation, including campaign chairman Paul Manafort, top deputy Rick Gates, campaign advisers Michael Flynn and George Papadopoulos, and Trump's personal lawyer Michael Cohen. Trump's longtime friend Roger Stone faces multiple criminal charges arising out of his attempts to conceal his contacts with WikiLeaks. If this was a witch hunt, it found a lot of witches.

The report establishes beyond doubt that a foreign rival engaged in a systematic effort to subvert our democracy. Tellingly, the Russians referred to their actions as "information warfare." One would think that any American president, regardless of ideology, would support a full-scale investigation to understand the extent of such interference and to help ward off future threats to our national sovereignty and security. Instead, Mueller's report shows that Trump's concern was not for American democracy, but for saving his own skin.

In both his initial letter to Congress and his press conference, Barr emphasized that Mueller did not charge Trump with the crime of obstruction of justice. What Barr did not say, however, was that Mueller declined to do so not because the evidence did not support the charge, but because he concluded that it would be inappropriate to level such a charge against a sitting president. The Department of Justice, Mueller noted, has taken the position that even a sitting president who has engaged in blatantly criminal activity cannot be indicted, because a jury of twelve citizens should not have the power to remove an elected president from office by a guilty verdict. Presidential crimes should be assessed by Congress in impeachment proceedings or by the public at the ballot box.

As special counsel, appointed by and reporting to the Justice Department, Mueller considered himself bound by its legal interpretation. He further reasoned that since he could not indict President Trump no matter how strong the evidence against him, it would be unfair to conclude in his report that Trump had committed a crime, because without a trial, Trump would not have an opportunity to clear his name. Thus Mueller's reticence stemmed from a concern for fairness, not from any doubt about the evidence. He noted that had he concluded that the president had not obstructed justice, he would have said so. Instead, he wrote that the report "does not exonerate" Trump.

"Presidential crimes should be assessed by Congress in impeachment proceedings or by the public at the ballot box."

That is classic Muellerian understatement. The report dispassionately lays out the facts, which are an indictment in all but name. Many of the incidents described had been reported previously, but often based on unnamed sources and reflexively derided by Trump and his supporters as "fake news." Mueller conducted a herculean two-year investigation, issuing more than 2,800 subpoenas, executing nearly 500 search warrants and 280 orders for electronic communications intercepts and records, and interviewing about 500 witnesses, 80 before a grand jury. The report rests its determinations of credibility on multiple named sources and thoroughly explains its reasoning. Its objective "just the facts" approach only underscores its veracity.

The results are devastating for Trump. The report portrays a consistent pattern of deception and repeated efforts to impede the Mueller investigation. The obstruction began with Trump's firing of FBI Director James Comey after he declined to end an investigation of National Security Adviser Michael Flynn. Mueller describes how Trump enlisted others, including Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, to conceal the motive for firing Comey by asserting that it was because of his handling of the Clinton e-mail investigation. (It's a mystery, given Rosenstein's involvement in this initial incident of obstruction, why he didn't have to recuse himself from overseeing the investigation, as Sessions did.)

Mueller also reveals that Trump directed White House Counsel Don McGahn to fire the special counsel on accusations of conflict of interest that Trump knew were groundless, and after this was reported by The New York Times, Trump instructed McGahn to lie about it. Trump lambasted Attorney General Sessions for recusing himself from overseeing the investigation, even though ethics rules required that Sessions do so because of his involvement in the campaign being investigated, and Trump repeatedly pressured Sessions to "unrecuse" himself. He met privately with his former campaign manager Corey Lewandowski and asked him to deliver a message to Sessions directing him to limit the special counsel investigation to future threats, thereby insulating the 2016 conduct by the Russians and the Trump campaign from inquiry. He personally interceded to delete from a statement about his son's meeting with a Russian lawyer any reference to the lawyer's offer to provide compromising information on Hillary Clinton. He encouraged important witnesses, including Cohen and Manafort, not to cooperate with the investigation. On multiple occasions, his staff simply refused to carry out his requests. As Mueller puts it, "The President's efforts to influence the investigation were mostly unsuccessful, but that is largely because the persons who surrounded the President declined to carry out orders or accede to his requests."

Some of Trump's defenders, including Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz and Trump's personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani, have argued that the president has the constitutional authority to terminate any federal prosecution and thus cannot be guilty of "obstructing justice." Mueller convincingly refutes that argument. He notes that obstruction of justice requires a "corrupt" intent, distinguishing between a decision that an investigation does not serve the nation's purposes, on the one hand, and efforts to conceal wrongdoing by oneself or one's family or associates, on the other. The latter, Mueller argues, is no more within the president's constitutional authority than would be a decision to curtail an investigation for a bribe. No reasonable reader can come away from the report with anything but the conclusion that the president repeatedly sought to obstruct an investigation into one of the most significant breaches of our sovereignty in generations, in order to avoid disclosure of embarrassing and illegal conduct by himself and his associates.

"[The report's] objective 'just the facts' approach only underscores its veracity... The results are devastating for Trump."

Trump triumphantly tweeted on the day of the report's release, "NO COLLUSION. NO OBSTRUCTION!" That he could consider such a damming and exhaustively sourced account of his own duplicitous and shameful acts an "exoneration" suggests three possibilities: (1) he had good reason to fear much worse; (2) he is still lying to the American public; or (3) he has such low expectations of what ethical leadership requires that he genuinely sees nothing wrong in what he did. Any of these explanations is deeply troubling for the nation.

What should be done now? The fact that a sitting president cannot be indicted does not mean that he cannot be called to account by other means. And some form of accountability is essential. What Trump has already done is profoundly damaging to the institution of the presidency and our system of justice, but we will make it worse if we collectively fail to demand a reckoning.

There are at least four ways to make clear that the president's conduct was unacceptable. The first is the most extreme and least likely: removal from office via impeachment. The determination that a sitting president cannot be indicted is partly based on the notion that the Constitution provides a different forum for addressing presidential criminality: impeachment by the House and trial by the Senate. Democratic presidential candidates Elizabeth Warren, Julian Castro, and Kamala Harris have already called on the House to pursue this course. There is no question that the Mueller report describes offenses that legally qualify as "high crimes and misdemeanors," which the Constitution identifies as grounds for impeachment. The articles of impeachment against Bill Clinton included obstruction of justice, as did those being drafted against Richard Nixon before he resigned. But impeachment is ultimately a political act, and at the moment there is zero likelihood that two-thirds of the Senate would vote to remove President Trump from office. The fact that Republican senators are virtually certain to reject impeachment despite Trump's egregious conduct underscores how hyperpartisanship has corroded our most fundamental principles. But the process of impeachment would likely make the nation's partisan divide even worse, and an acquittal by the Senate would send a message that a president can commit serious crimes with impunity as long as his party controls the Senate.

"No reasonable reader can come away from the report with anything but the conclusion that the president repeatedly sought to obstruct an investigation into one of the most significant breaches of our sovereignty in generations, in order to avoid disclosure of embarrassing and illegal conduct by himself and his associates."

Second, a president can be indicted after he leaves office for crimes he committed while president. It is therefore possible that a subsequent administration could pursue criminal charges against Trump, assuming the statute of limitations--five years in this case--has not run out. But it seems highly unlikely that a president who defeated Trump would expend his or her political capital on such a prosecution. President George W. Bush authorized torture, and President Obama did not seriously consider prosecuting him for doing so.

A third, more realistic form of accountability is for the House to continue its investigation of the Russian interference and Trump's conduct. At a minimum, that investigation will inform what Congress might do to ensure electoral integrity in the future. And while Mueller's investigation was thorough, it left one glaring hole. Despite claiming that he would be happy to answer Mueller's questions, Trump ultimately declined to answer a single question about his potential obstruction of justice. Mueller concluded that seeking to compel the president's testimony would have delayed the report. Congress can and should follow up by calling on major figures in the investigation, including Mueller, McGahn, Lewandowski, Donald Trump Jr., and President Trump himself to testify about his multiple efforts to impede the Mueller investigation.

The last and most important forum for judging Trump is the ballot box. He will almost certainly run for reelection in 2020, and voters will be able to decide whether he deserves a second term. Elections are determined by many factors, of course, so the 2020 vote will be a referendum on more than Trump's obstruction of justice. But it may be the best chance we have to call him to account for the actions the Mueller report has documented.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Special Counsel Robert Mueller's long-awaited report, released to the public in a redacted version on April 18, lays out in meticulous detail both a blatantly illegal effort by Russia to throw the 2016 presidential election to Donald Trump and repeated efforts by President Trump to end, limit, or impede Mueller's investigation of Russian interference. Trump's efforts included firing or attempting to fire those overseeing the investigation, directing subordinates to lie on his behalf, cajoling witnesses not to cooperate, and doctoring a public statement about a Trump Tower meeting between his son and closest advisers and a Russian lawyer offering compromising information on Hillary Clinton.

Attorney General William Barr, who has shown himself to be exactly the kind of presidential protector Trump wanted Jeff Sessions to be, did his best to whitewash the report. Almost four weeks before it was released to the public, Barr wrote a four-page letter to Congress purporting to summarize its findings. But as The New York Times's Charlie Savage has shown, in the letter Barr took Mueller's words out of context and omitted all mention of the damning evidence that courses through the report.* Just before releasing the report to the public, Barr also held a press conference in which he again distorted its conclusions, stating that it found no collusion with the Russians and no obstruction of justice by the president. Both statements are profoundly misleading.

"If this was a witch hunt, it found a lot of witches."

The Mueller report (pdf) did not address "collusion," a term that has no legal definition, but the narrower question of criminal conspiracy. It found no evidence that Trump campaign officials conspired with the Russians' disinformation campaigns or hacking of computers belonging to the Democratic National Committee and the Clinton campaign. But it describes extensive contacts between the Trump campaign and the Russians, many of which Trump campaign officials lied about. And it finds substantial evidence both "that the Russian government perceived it would benefit from a Trump presidency and worked to secure that outcome, and that the Campaign expected it would benefit electorally from information stolen and released through Russian efforts." Russian intelligence agency hackers targeted Hillary Clinton's home office within five hours of Trump's public request in July 2016 that the Russians find her deleted e-mails. And WikiLeaks, which was in close touch with Trump advisers, began releasing its trove of e-mails stolen by the Russians from Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta one hour after the Access Hollywood tape in which Trump bragged about assaulting women was made public in October 2016.

Trump has repeatedly dismissed the investigation as a "witch hunt." But Mueller found "sweeping and systematic" intrusions by Russia in the presidential campaign, all aimed at supporting Trump's election. He and his team indicted twenty-five Russians and secured the convictions or guilty pleas of several Trump campaign officials for lying in connection with the investigation, including campaign chairman Paul Manafort, top deputy Rick Gates, campaign advisers Michael Flynn and George Papadopoulos, and Trump's personal lawyer Michael Cohen. Trump's longtime friend Roger Stone faces multiple criminal charges arising out of his attempts to conceal his contacts with WikiLeaks. If this was a witch hunt, it found a lot of witches.

The report establishes beyond doubt that a foreign rival engaged in a systematic effort to subvert our democracy. Tellingly, the Russians referred to their actions as "information warfare." One would think that any American president, regardless of ideology, would support a full-scale investigation to understand the extent of such interference and to help ward off future threats to our national sovereignty and security. Instead, Mueller's report shows that Trump's concern was not for American democracy, but for saving his own skin.

In both his initial letter to Congress and his press conference, Barr emphasized that Mueller did not charge Trump with the crime of obstruction of justice. What Barr did not say, however, was that Mueller declined to do so not because the evidence did not support the charge, but because he concluded that it would be inappropriate to level such a charge against a sitting president. The Department of Justice, Mueller noted, has taken the position that even a sitting president who has engaged in blatantly criminal activity cannot be indicted, because a jury of twelve citizens should not have the power to remove an elected president from office by a guilty verdict. Presidential crimes should be assessed by Congress in impeachment proceedings or by the public at the ballot box.

As special counsel, appointed by and reporting to the Justice Department, Mueller considered himself bound by its legal interpretation. He further reasoned that since he could not indict President Trump no matter how strong the evidence against him, it would be unfair to conclude in his report that Trump had committed a crime, because without a trial, Trump would not have an opportunity to clear his name. Thus Mueller's reticence stemmed from a concern for fairness, not from any doubt about the evidence. He noted that had he concluded that the president had not obstructed justice, he would have said so. Instead, he wrote that the report "does not exonerate" Trump.

"Presidential crimes should be assessed by Congress in impeachment proceedings or by the public at the ballot box."

That is classic Muellerian understatement. The report dispassionately lays out the facts, which are an indictment in all but name. Many of the incidents described had been reported previously, but often based on unnamed sources and reflexively derided by Trump and his supporters as "fake news." Mueller conducted a herculean two-year investigation, issuing more than 2,800 subpoenas, executing nearly 500 search warrants and 280 orders for electronic communications intercepts and records, and interviewing about 500 witnesses, 80 before a grand jury. The report rests its determinations of credibility on multiple named sources and thoroughly explains its reasoning. Its objective "just the facts" approach only underscores its veracity.

The results are devastating for Trump. The report portrays a consistent pattern of deception and repeated efforts to impede the Mueller investigation. The obstruction began with Trump's firing of FBI Director James Comey after he declined to end an investigation of National Security Adviser Michael Flynn. Mueller describes how Trump enlisted others, including Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, to conceal the motive for firing Comey by asserting that it was because of his handling of the Clinton e-mail investigation. (It's a mystery, given Rosenstein's involvement in this initial incident of obstruction, why he didn't have to recuse himself from overseeing the investigation, as Sessions did.)

Mueller also reveals that Trump directed White House Counsel Don McGahn to fire the special counsel on accusations of conflict of interest that Trump knew were groundless, and after this was reported by The New York Times, Trump instructed McGahn to lie about it. Trump lambasted Attorney General Sessions for recusing himself from overseeing the investigation, even though ethics rules required that Sessions do so because of his involvement in the campaign being investigated, and Trump repeatedly pressured Sessions to "unrecuse" himself. He met privately with his former campaign manager Corey Lewandowski and asked him to deliver a message to Sessions directing him to limit the special counsel investigation to future threats, thereby insulating the 2016 conduct by the Russians and the Trump campaign from inquiry. He personally interceded to delete from a statement about his son's meeting with a Russian lawyer any reference to the lawyer's offer to provide compromising information on Hillary Clinton. He encouraged important witnesses, including Cohen and Manafort, not to cooperate with the investigation. On multiple occasions, his staff simply refused to carry out his requests. As Mueller puts it, "The President's efforts to influence the investigation were mostly unsuccessful, but that is largely because the persons who surrounded the President declined to carry out orders or accede to his requests."

Some of Trump's defenders, including Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz and Trump's personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani, have argued that the president has the constitutional authority to terminate any federal prosecution and thus cannot be guilty of "obstructing justice." Mueller convincingly refutes that argument. He notes that obstruction of justice requires a "corrupt" intent, distinguishing between a decision that an investigation does not serve the nation's purposes, on the one hand, and efforts to conceal wrongdoing by oneself or one's family or associates, on the other. The latter, Mueller argues, is no more within the president's constitutional authority than would be a decision to curtail an investigation for a bribe. No reasonable reader can come away from the report with anything but the conclusion that the president repeatedly sought to obstruct an investigation into one of the most significant breaches of our sovereignty in generations, in order to avoid disclosure of embarrassing and illegal conduct by himself and his associates.

"[The report's] objective 'just the facts' approach only underscores its veracity... The results are devastating for Trump."

Trump triumphantly tweeted on the day of the report's release, "NO COLLUSION. NO OBSTRUCTION!" That he could consider such a damming and exhaustively sourced account of his own duplicitous and shameful acts an "exoneration" suggests three possibilities: (1) he had good reason to fear much worse; (2) he is still lying to the American public; or (3) he has such low expectations of what ethical leadership requires that he genuinely sees nothing wrong in what he did. Any of these explanations is deeply troubling for the nation.

What should be done now? The fact that a sitting president cannot be indicted does not mean that he cannot be called to account by other means. And some form of accountability is essential. What Trump has already done is profoundly damaging to the institution of the presidency and our system of justice, but we will make it worse if we collectively fail to demand a reckoning.

There are at least four ways to make clear that the president's conduct was unacceptable. The first is the most extreme and least likely: removal from office via impeachment. The determination that a sitting president cannot be indicted is partly based on the notion that the Constitution provides a different forum for addressing presidential criminality: impeachment by the House and trial by the Senate. Democratic presidential candidates Elizabeth Warren, Julian Castro, and Kamala Harris have already called on the House to pursue this course. There is no question that the Mueller report describes offenses that legally qualify as "high crimes and misdemeanors," which the Constitution identifies as grounds for impeachment. The articles of impeachment against Bill Clinton included obstruction of justice, as did those being drafted against Richard Nixon before he resigned. But impeachment is ultimately a political act, and at the moment there is zero likelihood that two-thirds of the Senate would vote to remove President Trump from office. The fact that Republican senators are virtually certain to reject impeachment despite Trump's egregious conduct underscores how hyperpartisanship has corroded our most fundamental principles. But the process of impeachment would likely make the nation's partisan divide even worse, and an acquittal by the Senate would send a message that a president can commit serious crimes with impunity as long as his party controls the Senate.

"No reasonable reader can come away from the report with anything but the conclusion that the president repeatedly sought to obstruct an investigation into one of the most significant breaches of our sovereignty in generations, in order to avoid disclosure of embarrassing and illegal conduct by himself and his associates."

Second, a president can be indicted after he leaves office for crimes he committed while president. It is therefore possible that a subsequent administration could pursue criminal charges against Trump, assuming the statute of limitations--five years in this case--has not run out. But it seems highly unlikely that a president who defeated Trump would expend his or her political capital on such a prosecution. President George W. Bush authorized torture, and President Obama did not seriously consider prosecuting him for doing so.

A third, more realistic form of accountability is for the House to continue its investigation of the Russian interference and Trump's conduct. At a minimum, that investigation will inform what Congress might do to ensure electoral integrity in the future. And while Mueller's investigation was thorough, it left one glaring hole. Despite claiming that he would be happy to answer Mueller's questions, Trump ultimately declined to answer a single question about his potential obstruction of justice. Mueller concluded that seeking to compel the president's testimony would have delayed the report. Congress can and should follow up by calling on major figures in the investigation, including Mueller, McGahn, Lewandowski, Donald Trump Jr., and President Trump himself to testify about his multiple efforts to impede the Mueller investigation.

The last and most important forum for judging Trump is the ballot box. He will almost certainly run for reelection in 2020, and voters will be able to decide whether he deserves a second term. Elections are determined by many factors, of course, so the 2020 vote will be a referendum on more than Trump's obstruction of justice. But it may be the best chance we have to call him to account for the actions the Mueller report has documented.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller's long-awaited report, released to the public in a redacted version on April 18, lays out in meticulous detail both a blatantly illegal effort by Russia to throw the 2016 presidential election to Donald Trump and repeated efforts by President Trump to end, limit, or impede Mueller's investigation of Russian interference. Trump's efforts included firing or attempting to fire those overseeing the investigation, directing subordinates to lie on his behalf, cajoling witnesses not to cooperate, and doctoring a public statement about a Trump Tower meeting between his son and closest advisers and a Russian lawyer offering compromising information on Hillary Clinton.

Attorney General William Barr, who has shown himself to be exactly the kind of presidential protector Trump wanted Jeff Sessions to be, did his best to whitewash the report. Almost four weeks before it was released to the public, Barr wrote a four-page letter to Congress purporting to summarize its findings. But as The New York Times's Charlie Savage has shown, in the letter Barr took Mueller's words out of context and omitted all mention of the damning evidence that courses through the report.* Just before releasing the report to the public, Barr also held a press conference in which he again distorted its conclusions, stating that it found no collusion with the Russians and no obstruction of justice by the president. Both statements are profoundly misleading.

"If this was a witch hunt, it found a lot of witches."

The Mueller report (pdf) did not address "collusion," a term that has no legal definition, but the narrower question of criminal conspiracy. It found no evidence that Trump campaign officials conspired with the Russians' disinformation campaigns or hacking of computers belonging to the Democratic National Committee and the Clinton campaign. But it describes extensive contacts between the Trump campaign and the Russians, many of which Trump campaign officials lied about. And it finds substantial evidence both "that the Russian government perceived it would benefit from a Trump presidency and worked to secure that outcome, and that the Campaign expected it would benefit electorally from information stolen and released through Russian efforts." Russian intelligence agency hackers targeted Hillary Clinton's home office within five hours of Trump's public request in July 2016 that the Russians find her deleted e-mails. And WikiLeaks, which was in close touch with Trump advisers, began releasing its trove of e-mails stolen by the Russians from Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta one hour after the Access Hollywood tape in which Trump bragged about assaulting women was made public in October 2016.

Trump has repeatedly dismissed the investigation as a "witch hunt." But Mueller found "sweeping and systematic" intrusions by Russia in the presidential campaign, all aimed at supporting Trump's election. He and his team indicted twenty-five Russians and secured the convictions or guilty pleas of several Trump campaign officials for lying in connection with the investigation, including campaign chairman Paul Manafort, top deputy Rick Gates, campaign advisers Michael Flynn and George Papadopoulos, and Trump's personal lawyer Michael Cohen. Trump's longtime friend Roger Stone faces multiple criminal charges arising out of his attempts to conceal his contacts with WikiLeaks. If this was a witch hunt, it found a lot of witches.

The report establishes beyond doubt that a foreign rival engaged in a systematic effort to subvert our democracy. Tellingly, the Russians referred to their actions as "information warfare." One would think that any American president, regardless of ideology, would support a full-scale investigation to understand the extent of such interference and to help ward off future threats to our national sovereignty and security. Instead, Mueller's report shows that Trump's concern was not for American democracy, but for saving his own skin.

In both his initial letter to Congress and his press conference, Barr emphasized that Mueller did not charge Trump with the crime of obstruction of justice. What Barr did not say, however, was that Mueller declined to do so not because the evidence did not support the charge, but because he concluded that it would be inappropriate to level such a charge against a sitting president. The Department of Justice, Mueller noted, has taken the position that even a sitting president who has engaged in blatantly criminal activity cannot be indicted, because a jury of twelve citizens should not have the power to remove an elected president from office by a guilty verdict. Presidential crimes should be assessed by Congress in impeachment proceedings or by the public at the ballot box.

As special counsel, appointed by and reporting to the Justice Department, Mueller considered himself bound by its legal interpretation. He further reasoned that since he could not indict President Trump no matter how strong the evidence against him, it would be unfair to conclude in his report that Trump had committed a crime, because without a trial, Trump would not have an opportunity to clear his name. Thus Mueller's reticence stemmed from a concern for fairness, not from any doubt about the evidence. He noted that had he concluded that the president had not obstructed justice, he would have said so. Instead, he wrote that the report "does not exonerate" Trump.

"Presidential crimes should be assessed by Congress in impeachment proceedings or by the public at the ballot box."

That is classic Muellerian understatement. The report dispassionately lays out the facts, which are an indictment in all but name. Many of the incidents described had been reported previously, but often based on unnamed sources and reflexively derided by Trump and his supporters as "fake news." Mueller conducted a herculean two-year investigation, issuing more than 2,800 subpoenas, executing nearly 500 search warrants and 280 orders for electronic communications intercepts and records, and interviewing about 500 witnesses, 80 before a grand jury. The report rests its determinations of credibility on multiple named sources and thoroughly explains its reasoning. Its objective "just the facts" approach only underscores its veracity.

The results are devastating for Trump. The report portrays a consistent pattern of deception and repeated efforts to impede the Mueller investigation. The obstruction began with Trump's firing of FBI Director James Comey after he declined to end an investigation of National Security Adviser Michael Flynn. Mueller describes how Trump enlisted others, including Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, to conceal the motive for firing Comey by asserting that it was because of his handling of the Clinton e-mail investigation. (It's a mystery, given Rosenstein's involvement in this initial incident of obstruction, why he didn't have to recuse himself from overseeing the investigation, as Sessions did.)

Mueller also reveals that Trump directed White House Counsel Don McGahn to fire the special counsel on accusations of conflict of interest that Trump knew were groundless, and after this was reported by The New York Times, Trump instructed McGahn to lie about it. Trump lambasted Attorney General Sessions for recusing himself from overseeing the investigation, even though ethics rules required that Sessions do so because of his involvement in the campaign being investigated, and Trump repeatedly pressured Sessions to "unrecuse" himself. He met privately with his former campaign manager Corey Lewandowski and asked him to deliver a message to Sessions directing him to limit the special counsel investigation to future threats, thereby insulating the 2016 conduct by the Russians and the Trump campaign from inquiry. He personally interceded to delete from a statement about his son's meeting with a Russian lawyer any reference to the lawyer's offer to provide compromising information on Hillary Clinton. He encouraged important witnesses, including Cohen and Manafort, not to cooperate with the investigation. On multiple occasions, his staff simply refused to carry out his requests. As Mueller puts it, "The President's efforts to influence the investigation were mostly unsuccessful, but that is largely because the persons who surrounded the President declined to carry out orders or accede to his requests."

Some of Trump's defenders, including Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz and Trump's personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani, have argued that the president has the constitutional authority to terminate any federal prosecution and thus cannot be guilty of "obstructing justice." Mueller convincingly refutes that argument. He notes that obstruction of justice requires a "corrupt" intent, distinguishing between a decision that an investigation does not serve the nation's purposes, on the one hand, and efforts to conceal wrongdoing by oneself or one's family or associates, on the other. The latter, Mueller argues, is no more within the president's constitutional authority than would be a decision to curtail an investigation for a bribe. No reasonable reader can come away from the report with anything but the conclusion that the president repeatedly sought to obstruct an investigation into one of the most significant breaches of our sovereignty in generations, in order to avoid disclosure of embarrassing and illegal conduct by himself and his associates.

"[The report's] objective 'just the facts' approach only underscores its veracity... The results are devastating for Trump."

Trump triumphantly tweeted on the day of the report's release, "NO COLLUSION. NO OBSTRUCTION!" That he could consider such a damming and exhaustively sourced account of his own duplicitous and shameful acts an "exoneration" suggests three possibilities: (1) he had good reason to fear much worse; (2) he is still lying to the American public; or (3) he has such low expectations of what ethical leadership requires that he genuinely sees nothing wrong in what he did. Any of these explanations is deeply troubling for the nation.

What should be done now? The fact that a sitting president cannot be indicted does not mean that he cannot be called to account by other means. And some form of accountability is essential. What Trump has already done is profoundly damaging to the institution of the presidency and our system of justice, but we will make it worse if we collectively fail to demand a reckoning.

There are at least four ways to make clear that the president's conduct was unacceptable. The first is the most extreme and least likely: removal from office via impeachment. The determination that a sitting president cannot be indicted is partly based on the notion that the Constitution provides a different forum for addressing presidential criminality: impeachment by the House and trial by the Senate. Democratic presidential candidates Elizabeth Warren, Julian Castro, and Kamala Harris have already called on the House to pursue this course. There is no question that the Mueller report describes offenses that legally qualify as "high crimes and misdemeanors," which the Constitution identifies as grounds for impeachment. The articles of impeachment against Bill Clinton included obstruction of justice, as did those being drafted against Richard Nixon before he resigned. But impeachment is ultimately a political act, and at the moment there is zero likelihood that two-thirds of the Senate would vote to remove President Trump from office. The fact that Republican senators are virtually certain to reject impeachment despite Trump's egregious conduct underscores how hyperpartisanship has corroded our most fundamental principles. But the process of impeachment would likely make the nation's partisan divide even worse, and an acquittal by the Senate would send a message that a president can commit serious crimes with impunity as long as his party controls the Senate.

"No reasonable reader can come away from the report with anything but the conclusion that the president repeatedly sought to obstruct an investigation into one of the most significant breaches of our sovereignty in generations, in order to avoid disclosure of embarrassing and illegal conduct by himself and his associates."

Second, a president can be indicted after he leaves office for crimes he committed while president. It is therefore possible that a subsequent administration could pursue criminal charges against Trump, assuming the statute of limitations--five years in this case--has not run out. But it seems highly unlikely that a president who defeated Trump would expend his or her political capital on such a prosecution. President George W. Bush authorized torture, and President Obama did not seriously consider prosecuting him for doing so.

A third, more realistic form of accountability is for the House to continue its investigation of the Russian interference and Trump's conduct. At a minimum, that investigation will inform what Congress might do to ensure electoral integrity in the future. And while Mueller's investigation was thorough, it left one glaring hole. Despite claiming that he would be happy to answer Mueller's questions, Trump ultimately declined to answer a single question about his potential obstruction of justice. Mueller concluded that seeking to compel the president's testimony would have delayed the report. Congress can and should follow up by calling on major figures in the investigation, including Mueller, McGahn, Lewandowski, Donald Trump Jr., and President Trump himself to testify about his multiple efforts to impede the Mueller investigation.

The last and most important forum for judging Trump is the ballot box. He will almost certainly run for reelection in 2020, and voters will be able to decide whether he deserves a second term. Elections are determined by many factors, of course, so the 2020 vote will be a referendum on more than Trump's obstruction of justice. But it may be the best chance we have to call him to account for the actions the Mueller report has documented.