A Balanced Budget Amendment (BBA), writes Kogan, "is a fundamentally unsound policy idea." (Photo: Bjorn Wylezich/Dreamstime)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

A Balanced Budget Amendment (BBA), writes Kogan, "is a fundamentally unsound policy idea." (Photo: Bjorn Wylezich/Dreamstime)

Members of Congress have proposed almost a dozen constitutional amendments this year requiring a balanced budget, all of which share serious drawbacks. Rep. Ben McAdams introduced the latest balanced budget amendment (BBA), H.J. Res. 55, and it shows both that BBAs are fundamentally flawed and that attempts to fix them invariably don't succeed at doing that.

That's true mainly for five reasons:

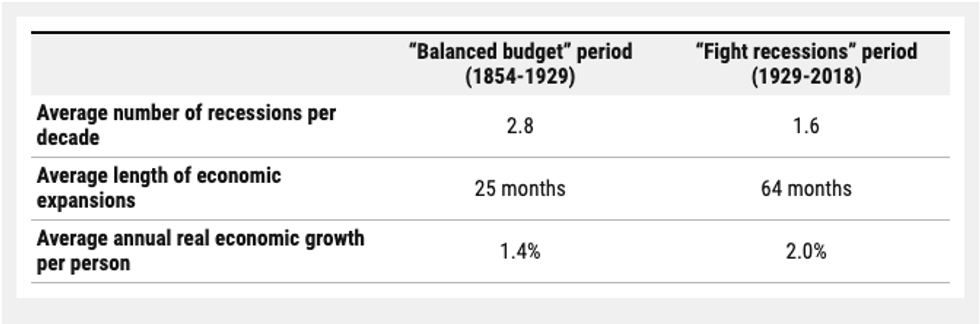

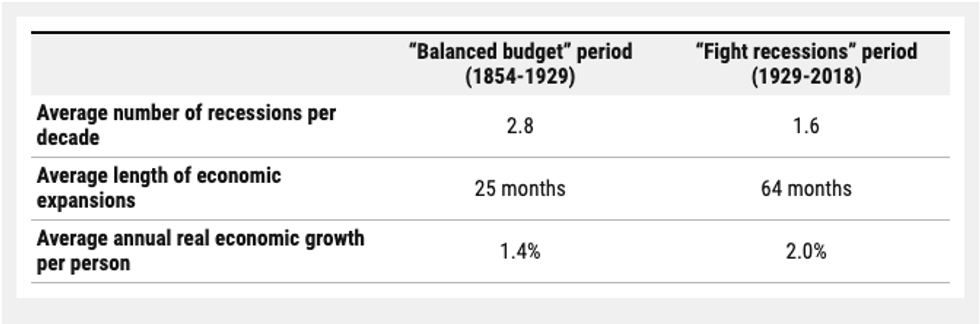

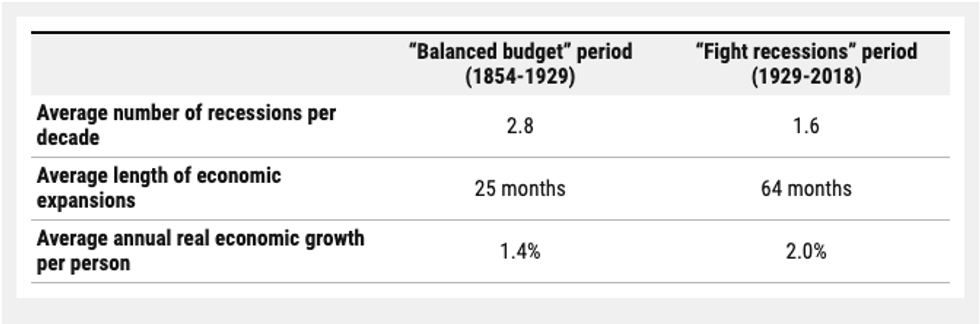

Before 1929, the budget was balanced or close to it in most years (except during major wars). From 1933 on, however, the federal government fought recessions by allowing deficits to grow when the economy was weak and then to shrink as it recovered. The latter approach worked better, with fewer recessions, longer expansions, and better growth, as the table shows:

H.J. Res. 55 acknowledges the problem but wouldn't fully solve it, and it would intensify the risk to other critical programs. It would exempt Social Security's trust fund and Medicare's Part A trust fund (which covers hospitalizations) from the balanced budget calculations. But that's only a partial solution; the FDIC, for instance, has almost $100 billion in reserves to protect checking and savings accounts against bank failures; H.J. Res. 55 would prohibit using those balances if that would throw the budget into deficit. Yet deposit insurance is needed most just when the economy is weakest and the budget is already in deficit.

Moreover, the Social Security and Medicare trust fund exclusions would put the rest of the budget in greater danger. Social Security and Medicare hospitalization are one-third of the budget. Suppose those two trust funds are in balance or surplus but the rest of the budget is not. A typical BBA, if it were in effect for next year, might then require an average cut of, say, 22 percent in all federal programs. But under H.J. Res 55, with Social Security and Medicare Part A protected, all remaining programs would face an average cut of 33 percent -- including Medicaid, SNAP (food stamps), Supplemental Security Income, unemployment insurance, assisted housing, national defense, veterans' benefits, law enforcement, education, and transportation.

A BBA is a fundamentally unsound policy idea. In its attempts to address its flaws, H.J. Res. 55 simply highlights that a BBA isn't fixable

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Members of Congress have proposed almost a dozen constitutional amendments this year requiring a balanced budget, all of which share serious drawbacks. Rep. Ben McAdams introduced the latest balanced budget amendment (BBA), H.J. Res. 55, and it shows both that BBAs are fundamentally flawed and that attempts to fix them invariably don't succeed at doing that.

That's true mainly for five reasons:

Before 1929, the budget was balanced or close to it in most years (except during major wars). From 1933 on, however, the federal government fought recessions by allowing deficits to grow when the economy was weak and then to shrink as it recovered. The latter approach worked better, with fewer recessions, longer expansions, and better growth, as the table shows:

H.J. Res. 55 acknowledges the problem but wouldn't fully solve it, and it would intensify the risk to other critical programs. It would exempt Social Security's trust fund and Medicare's Part A trust fund (which covers hospitalizations) from the balanced budget calculations. But that's only a partial solution; the FDIC, for instance, has almost $100 billion in reserves to protect checking and savings accounts against bank failures; H.J. Res. 55 would prohibit using those balances if that would throw the budget into deficit. Yet deposit insurance is needed most just when the economy is weakest and the budget is already in deficit.

Moreover, the Social Security and Medicare trust fund exclusions would put the rest of the budget in greater danger. Social Security and Medicare hospitalization are one-third of the budget. Suppose those two trust funds are in balance or surplus but the rest of the budget is not. A typical BBA, if it were in effect for next year, might then require an average cut of, say, 22 percent in all federal programs. But under H.J. Res 55, with Social Security and Medicare Part A protected, all remaining programs would face an average cut of 33 percent -- including Medicaid, SNAP (food stamps), Supplemental Security Income, unemployment insurance, assisted housing, national defense, veterans' benefits, law enforcement, education, and transportation.

A BBA is a fundamentally unsound policy idea. In its attempts to address its flaws, H.J. Res. 55 simply highlights that a BBA isn't fixable

Members of Congress have proposed almost a dozen constitutional amendments this year requiring a balanced budget, all of which share serious drawbacks. Rep. Ben McAdams introduced the latest balanced budget amendment (BBA), H.J. Res. 55, and it shows both that BBAs are fundamentally flawed and that attempts to fix them invariably don't succeed at doing that.

That's true mainly for five reasons:

Before 1929, the budget was balanced or close to it in most years (except during major wars). From 1933 on, however, the federal government fought recessions by allowing deficits to grow when the economy was weak and then to shrink as it recovered. The latter approach worked better, with fewer recessions, longer expansions, and better growth, as the table shows:

H.J. Res. 55 acknowledges the problem but wouldn't fully solve it, and it would intensify the risk to other critical programs. It would exempt Social Security's trust fund and Medicare's Part A trust fund (which covers hospitalizations) from the balanced budget calculations. But that's only a partial solution; the FDIC, for instance, has almost $100 billion in reserves to protect checking and savings accounts against bank failures; H.J. Res. 55 would prohibit using those balances if that would throw the budget into deficit. Yet deposit insurance is needed most just when the economy is weakest and the budget is already in deficit.

Moreover, the Social Security and Medicare trust fund exclusions would put the rest of the budget in greater danger. Social Security and Medicare hospitalization are one-third of the budget. Suppose those two trust funds are in balance or surplus but the rest of the budget is not. A typical BBA, if it were in effect for next year, might then require an average cut of, say, 22 percent in all federal programs. But under H.J. Res 55, with Social Security and Medicare Part A protected, all remaining programs would face an average cut of 33 percent -- including Medicaid, SNAP (food stamps), Supplemental Security Income, unemployment insurance, assisted housing, national defense, veterans' benefits, law enforcement, education, and transportation.

A BBA is a fundamentally unsound policy idea. In its attempts to address its flaws, H.J. Res. 55 simply highlights that a BBA isn't fixable