SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Per the ACLU, "data from Rochester and Troy reveal that nuisance ordinance enforcement happens more often in neighborhoods with higher percentages of residents of color." (Photo: Jason Lawrence/Flickr/cc)

In cities and towns across New York state--and around the country--you can be evicted just for calling for police or emergency assistance. Fortunately, that's about to change in New York. The State Legislature recently passed a bill--unanimously in the Assembly and 58 to 1 in the Senate--to protect tenants from eviction based on their calls for help.

What we learned mirrors what we know about enforcement of these ordinances across the nation: the brunt falls disproportionately on survivors of domestic violence, forcing them to endure threats and violence without police intervention or to risk losing their homes.

Cities often enact local laws called nuisance ordinances that label certain properties as "nuisances" based on the amount of 911 calls or emergency responses at that property, regardless of the reason for the call, the tenant's role in the dispute, or whether the person was requesting medical assistance.

When a property is the site of "too many" 911 responses, the city may punish the property owner with penalties such as fines, revocation of rental permits, or orders of closure. In order to avoid these consequences, landlords often evict or threaten to evict the tenants who called 911, refuse to renew their leases, or tell them to stop calling for help.

The NYCLU and ACLU surveyed New York's 80 most populous cities, towns, and villages to find out whether they had nuisance ordinances and how they were being enforced. What we learned mirrors what we know about enforcement of these ordinances across the nation: the brunt falls disproportionately on survivors of domestic violence, forcing them to endure threats and violence without police intervention or to risk losing their homes. For example, in both Fulton and Binghamton, domestic violence was the single largest category of activity that led to nuisance ordinance enforcement. These ordinances also hurt those in need of frequent medical attention, including the disabled and the elderly. And they are more commonly enforced in poor communities and communities of color.*

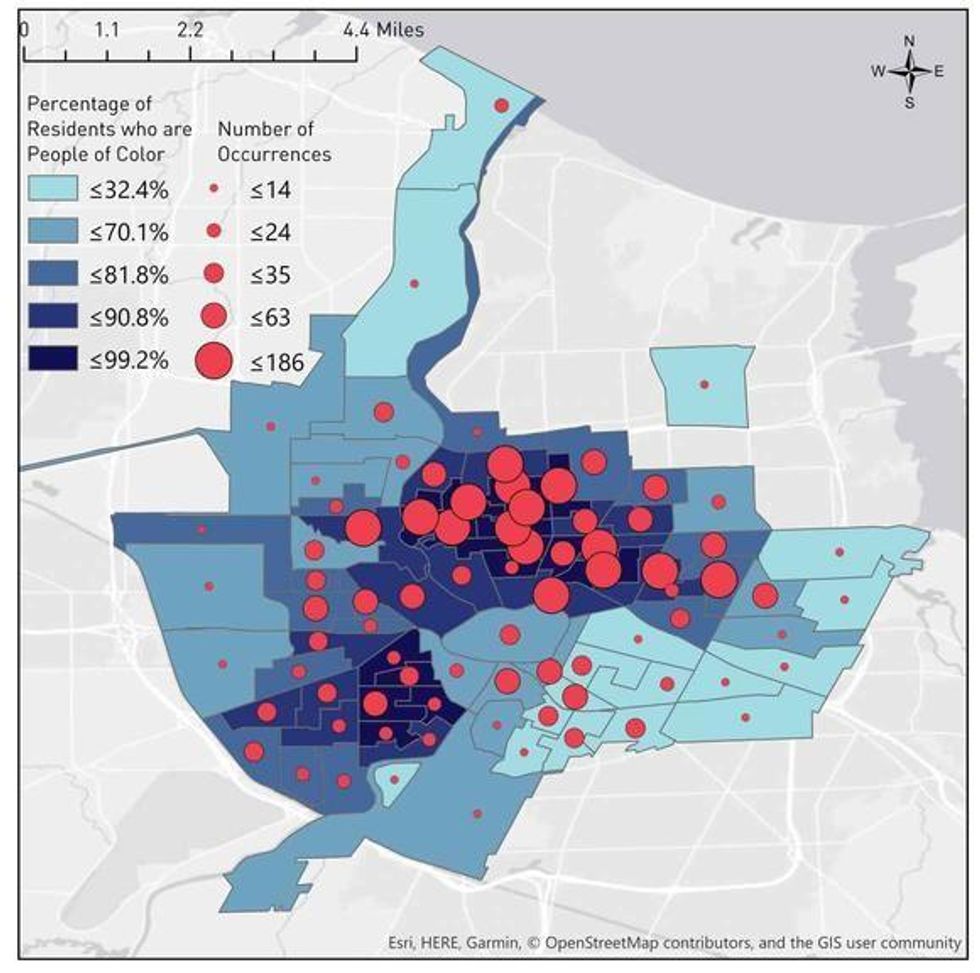

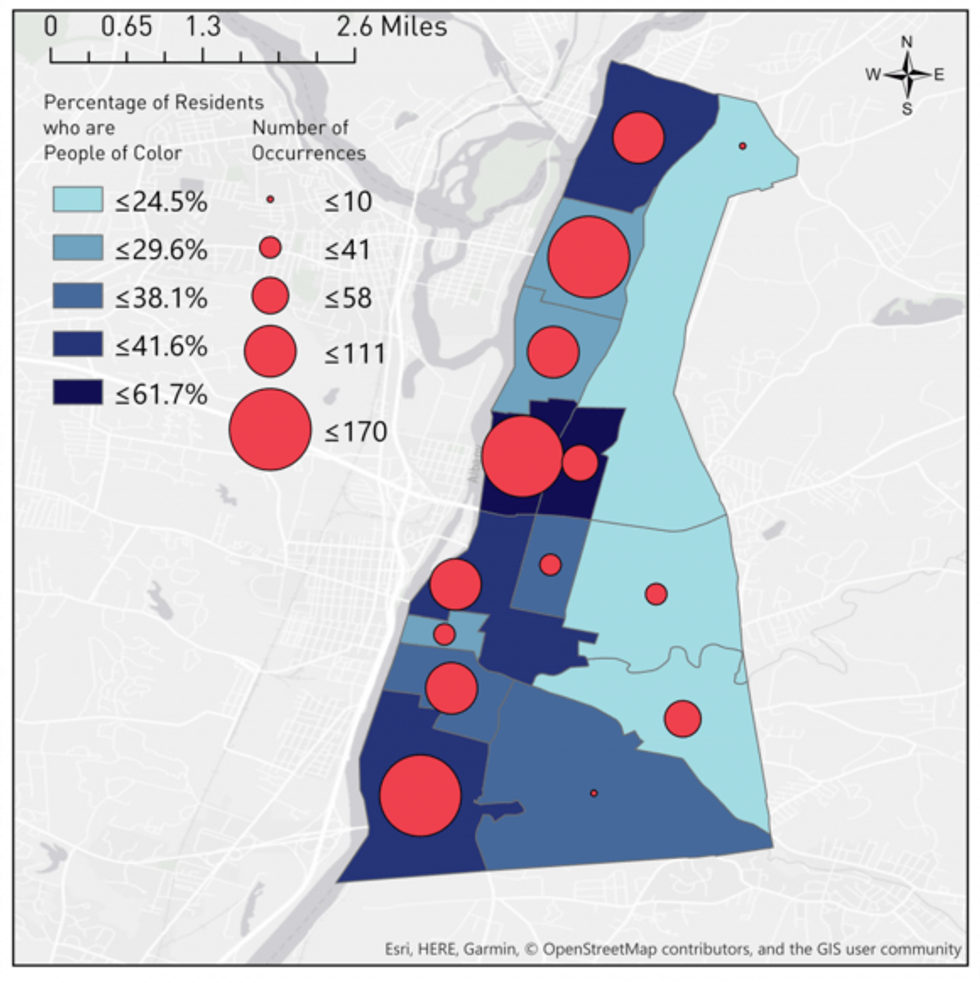

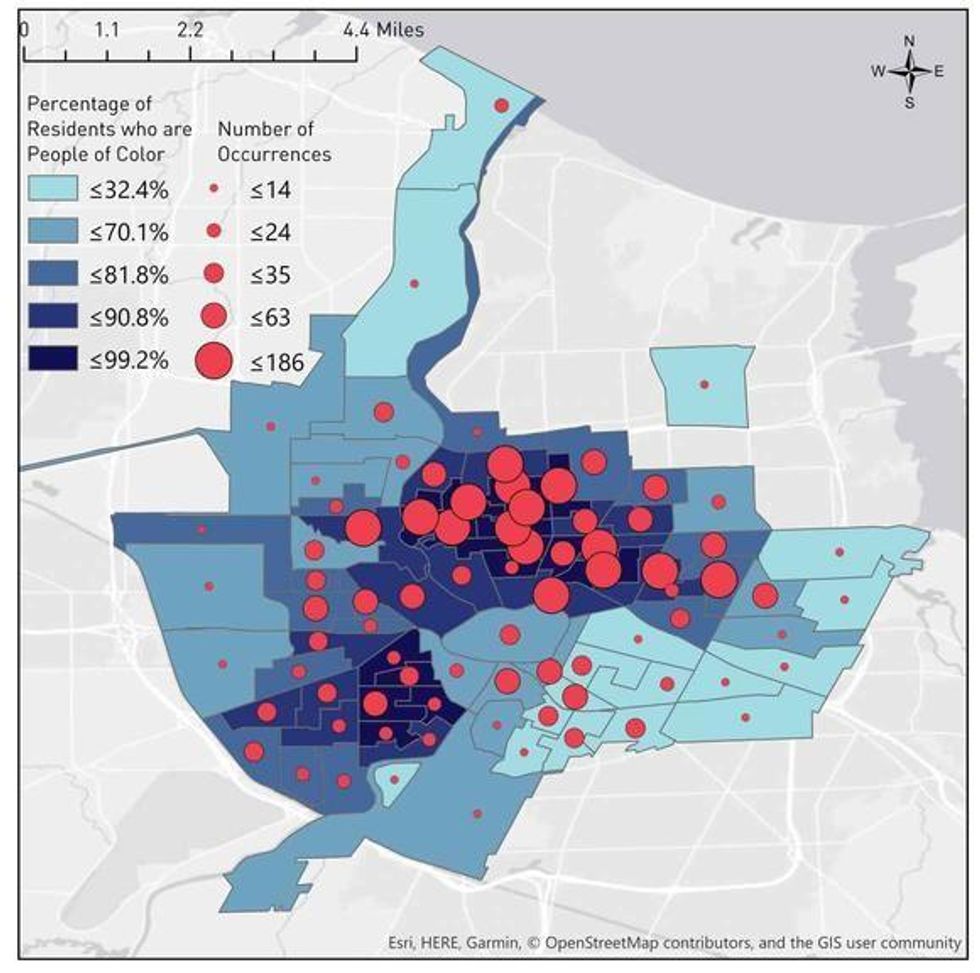

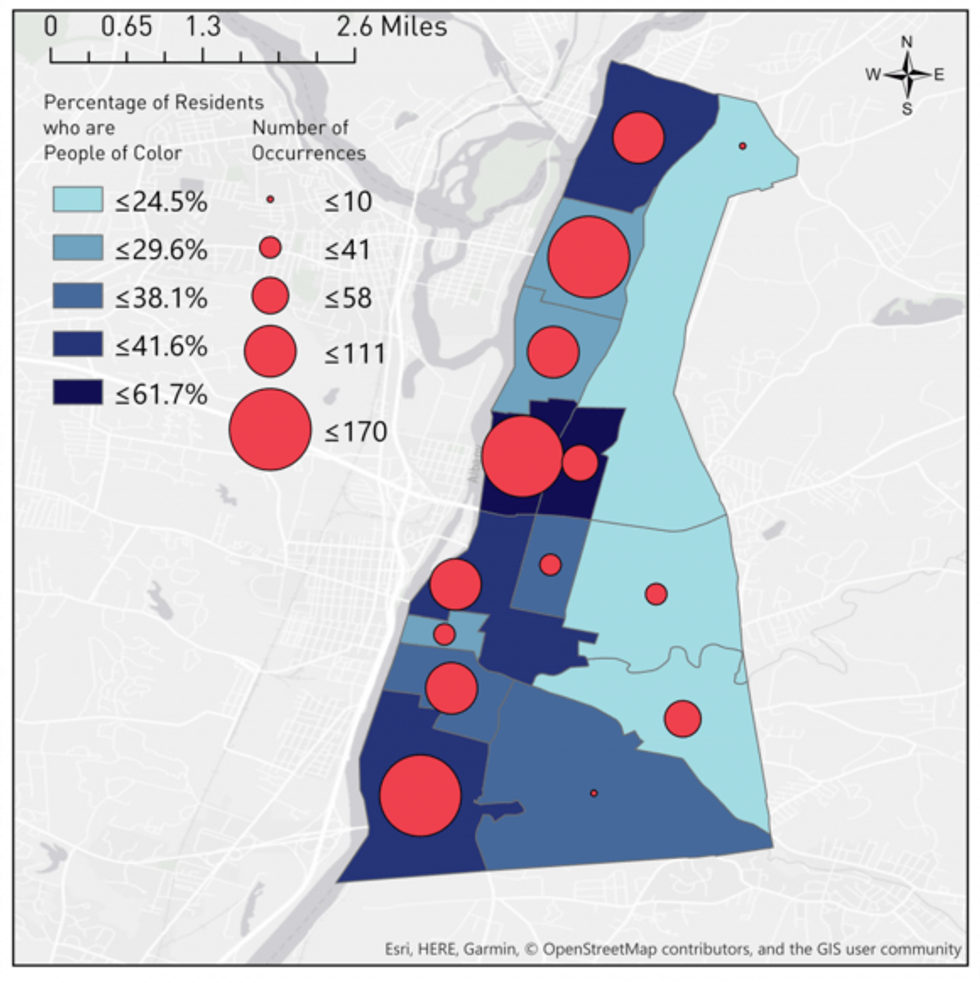

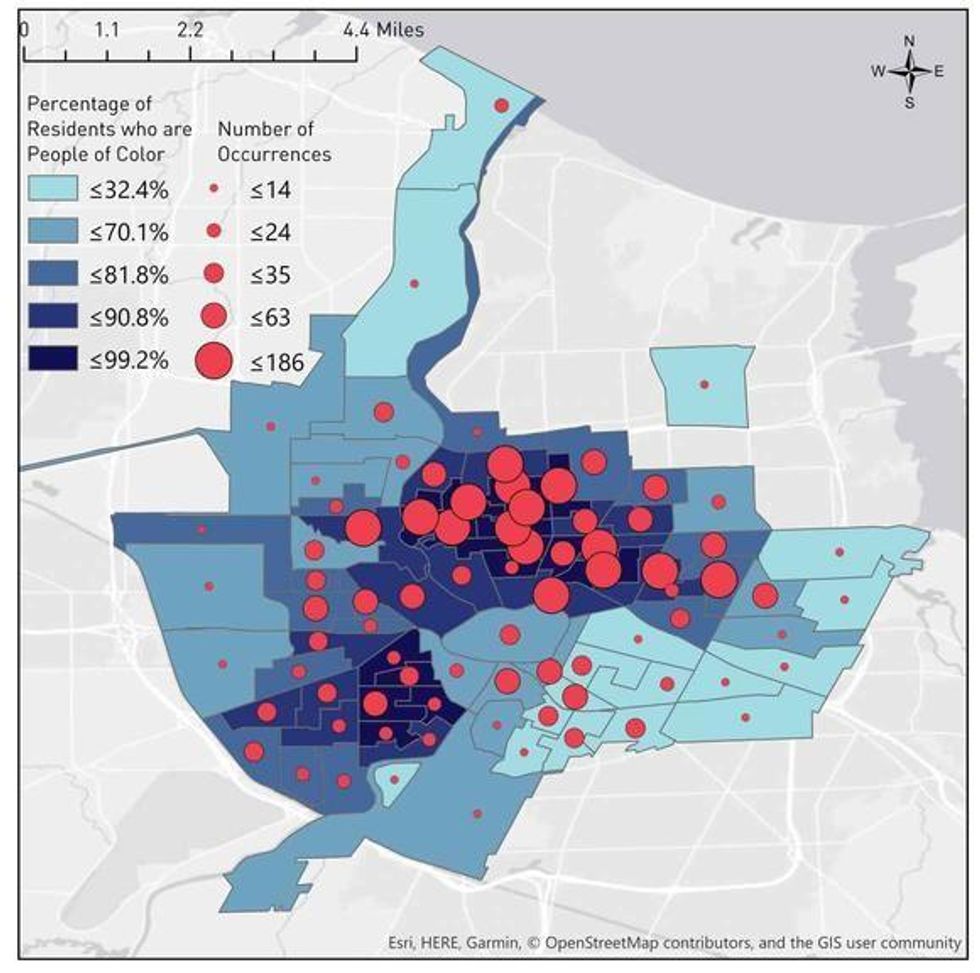

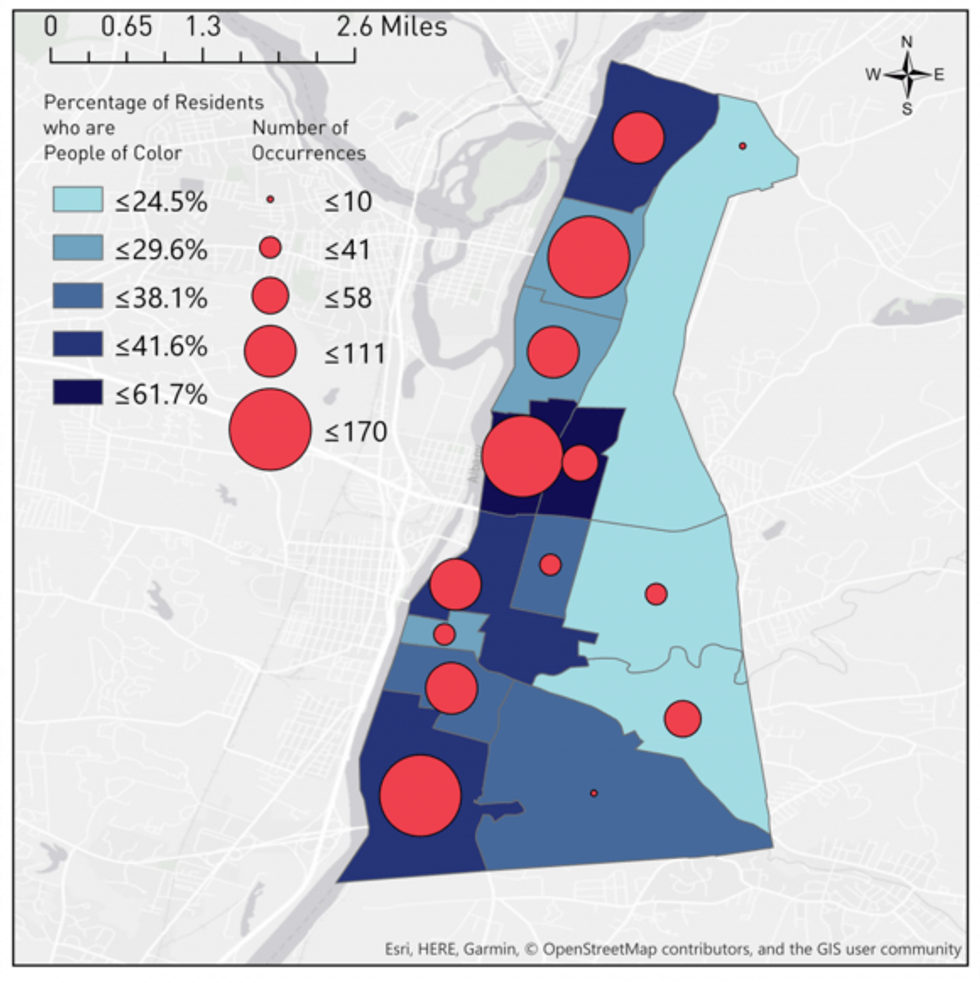

For example, data from Rochester and Troy reveal that nuisance ordinance enforcement happens more often in neighborhoods with higher percentages of residents of color. We also found that enforcement is more frequent in neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty, which makes it even harder for people who are already struggling financially to keep their homes.

Nuisance ordinances harm landlords as well by forcing them into an impossible choice. They can either let tenants who have called for help stay in their homes and risk getting fined or having their property taken away. Or they can kick their tenants out, which violates laws that prohibit evicting people for seeking government assistance.

The lopsided vote count may make it look like this legislation is a no-brainer. But we, along with the Empire State Justice Center and the New York State Coalition Against Domestic Violence, have been working to get this bill passed for a long time.

If Governor Cuomo signs the legislation into law as expected, New York will be the tenth state (plus the District of Columbia) to pass this type of bill. The ACLU wants to make these safeguards the law of the land nationwide. We are calling on the U.S. Senate to address this issue by supporting the housing protections in the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019, which passed the House in April. These protections would ensure that cities across the country cannot threaten people's housing because they called for help.

The graphics below represent actual nuisance ordinance enforcement data in the cities of Rochester (top) and Troy (bottom) from 2012-2018. Each map shows census tracts by proportion of residents of color, with lighter shading representing higher proportions of white residents and darker shading representing higher percentages of residents of color. Circles represent relative numbers of nuisance ordinance enforcement.

The figures below demonstrate the race and poverty profiles of the census tracts in Rochester where nuisance ordinances are least enforced to evict tenants and where they are most enforced to evict tenants for the period 2012-2018.

LEAST ENFORCEMENT | |

| Race | |

| White | 85.4% |

| Black | 8.7% |

| Hispanic | 2.1% |

| Other | 3.8% |

| Poverty | |

| Median Household Income | $65,819 |

| Below Poverty Line | 18.0% |

| Receiving Food Stamps | 3.1% |

| MOST ENFORCEMENT | |

| Race | |

| White | 4.5% |

| Black | 49.2% |

| Hispanic | 42.8% |

| Other | 3.5% |

| Poverty | |

| Median Household Income | $18,438 |

| Below Poverty Line | 37.6% |

| Receiving Food Stamps | 58.6% |

*A full disparate impact analysis is not possible due to the limited enforcement data we received.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

In cities and towns across New York state--and around the country--you can be evicted just for calling for police or emergency assistance. Fortunately, that's about to change in New York. The State Legislature recently passed a bill--unanimously in the Assembly and 58 to 1 in the Senate--to protect tenants from eviction based on their calls for help.

What we learned mirrors what we know about enforcement of these ordinances across the nation: the brunt falls disproportionately on survivors of domestic violence, forcing them to endure threats and violence without police intervention or to risk losing their homes.

Cities often enact local laws called nuisance ordinances that label certain properties as "nuisances" based on the amount of 911 calls or emergency responses at that property, regardless of the reason for the call, the tenant's role in the dispute, or whether the person was requesting medical assistance.

When a property is the site of "too many" 911 responses, the city may punish the property owner with penalties such as fines, revocation of rental permits, or orders of closure. In order to avoid these consequences, landlords often evict or threaten to evict the tenants who called 911, refuse to renew their leases, or tell them to stop calling for help.

The NYCLU and ACLU surveyed New York's 80 most populous cities, towns, and villages to find out whether they had nuisance ordinances and how they were being enforced. What we learned mirrors what we know about enforcement of these ordinances across the nation: the brunt falls disproportionately on survivors of domestic violence, forcing them to endure threats and violence without police intervention or to risk losing their homes. For example, in both Fulton and Binghamton, domestic violence was the single largest category of activity that led to nuisance ordinance enforcement. These ordinances also hurt those in need of frequent medical attention, including the disabled and the elderly. And they are more commonly enforced in poor communities and communities of color.*

For example, data from Rochester and Troy reveal that nuisance ordinance enforcement happens more often in neighborhoods with higher percentages of residents of color. We also found that enforcement is more frequent in neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty, which makes it even harder for people who are already struggling financially to keep their homes.

Nuisance ordinances harm landlords as well by forcing them into an impossible choice. They can either let tenants who have called for help stay in their homes and risk getting fined or having their property taken away. Or they can kick their tenants out, which violates laws that prohibit evicting people for seeking government assistance.

The lopsided vote count may make it look like this legislation is a no-brainer. But we, along with the Empire State Justice Center and the New York State Coalition Against Domestic Violence, have been working to get this bill passed for a long time.

If Governor Cuomo signs the legislation into law as expected, New York will be the tenth state (plus the District of Columbia) to pass this type of bill. The ACLU wants to make these safeguards the law of the land nationwide. We are calling on the U.S. Senate to address this issue by supporting the housing protections in the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019, which passed the House in April. These protections would ensure that cities across the country cannot threaten people's housing because they called for help.

The graphics below represent actual nuisance ordinance enforcement data in the cities of Rochester (top) and Troy (bottom) from 2012-2018. Each map shows census tracts by proportion of residents of color, with lighter shading representing higher proportions of white residents and darker shading representing higher percentages of residents of color. Circles represent relative numbers of nuisance ordinance enforcement.

The figures below demonstrate the race and poverty profiles of the census tracts in Rochester where nuisance ordinances are least enforced to evict tenants and where they are most enforced to evict tenants for the period 2012-2018.

LEAST ENFORCEMENT | |

| Race | |

| White | 85.4% |

| Black | 8.7% |

| Hispanic | 2.1% |

| Other | 3.8% |

| Poverty | |

| Median Household Income | $65,819 |

| Below Poverty Line | 18.0% |

| Receiving Food Stamps | 3.1% |

| MOST ENFORCEMENT | |

| Race | |

| White | 4.5% |

| Black | 49.2% |

| Hispanic | 42.8% |

| Other | 3.5% |

| Poverty | |

| Median Household Income | $18,438 |

| Below Poverty Line | 37.6% |

| Receiving Food Stamps | 58.6% |

*A full disparate impact analysis is not possible due to the limited enforcement data we received.

In cities and towns across New York state--and around the country--you can be evicted just for calling for police or emergency assistance. Fortunately, that's about to change in New York. The State Legislature recently passed a bill--unanimously in the Assembly and 58 to 1 in the Senate--to protect tenants from eviction based on their calls for help.

What we learned mirrors what we know about enforcement of these ordinances across the nation: the brunt falls disproportionately on survivors of domestic violence, forcing them to endure threats and violence without police intervention or to risk losing their homes.

Cities often enact local laws called nuisance ordinances that label certain properties as "nuisances" based on the amount of 911 calls or emergency responses at that property, regardless of the reason for the call, the tenant's role in the dispute, or whether the person was requesting medical assistance.

When a property is the site of "too many" 911 responses, the city may punish the property owner with penalties such as fines, revocation of rental permits, or orders of closure. In order to avoid these consequences, landlords often evict or threaten to evict the tenants who called 911, refuse to renew their leases, or tell them to stop calling for help.

The NYCLU and ACLU surveyed New York's 80 most populous cities, towns, and villages to find out whether they had nuisance ordinances and how they were being enforced. What we learned mirrors what we know about enforcement of these ordinances across the nation: the brunt falls disproportionately on survivors of domestic violence, forcing them to endure threats and violence without police intervention or to risk losing their homes. For example, in both Fulton and Binghamton, domestic violence was the single largest category of activity that led to nuisance ordinance enforcement. These ordinances also hurt those in need of frequent medical attention, including the disabled and the elderly. And they are more commonly enforced in poor communities and communities of color.*

For example, data from Rochester and Troy reveal that nuisance ordinance enforcement happens more often in neighborhoods with higher percentages of residents of color. We also found that enforcement is more frequent in neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty, which makes it even harder for people who are already struggling financially to keep their homes.

Nuisance ordinances harm landlords as well by forcing them into an impossible choice. They can either let tenants who have called for help stay in their homes and risk getting fined or having their property taken away. Or they can kick their tenants out, which violates laws that prohibit evicting people for seeking government assistance.

The lopsided vote count may make it look like this legislation is a no-brainer. But we, along with the Empire State Justice Center and the New York State Coalition Against Domestic Violence, have been working to get this bill passed for a long time.

If Governor Cuomo signs the legislation into law as expected, New York will be the tenth state (plus the District of Columbia) to pass this type of bill. The ACLU wants to make these safeguards the law of the land nationwide. We are calling on the U.S. Senate to address this issue by supporting the housing protections in the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019, which passed the House in April. These protections would ensure that cities across the country cannot threaten people's housing because they called for help.

The graphics below represent actual nuisance ordinance enforcement data in the cities of Rochester (top) and Troy (bottom) from 2012-2018. Each map shows census tracts by proportion of residents of color, with lighter shading representing higher proportions of white residents and darker shading representing higher percentages of residents of color. Circles represent relative numbers of nuisance ordinance enforcement.

The figures below demonstrate the race and poverty profiles of the census tracts in Rochester where nuisance ordinances are least enforced to evict tenants and where they are most enforced to evict tenants for the period 2012-2018.

LEAST ENFORCEMENT | |

| Race | |

| White | 85.4% |

| Black | 8.7% |

| Hispanic | 2.1% |

| Other | 3.8% |

| Poverty | |

| Median Household Income | $65,819 |

| Below Poverty Line | 18.0% |

| Receiving Food Stamps | 3.1% |

| MOST ENFORCEMENT | |

| Race | |

| White | 4.5% |

| Black | 49.2% |

| Hispanic | 42.8% |

| Other | 3.5% |

| Poverty | |

| Median Household Income | $18,438 |

| Below Poverty Line | 37.6% |

| Receiving Food Stamps | 58.6% |

*A full disparate impact analysis is not possible due to the limited enforcement data we received.