I emailed Stephanie Nebehay of Reuters on May 22 about her article, "Venezuela Turns to Russia, Cuba, China in Health Crisis" (5/22/19). Her article depicted the impact of US sanctions as an allegation that Venezuelan government officials are alone in making. The article stated:

The opposition blames [medical shortages] on economic incompetence and corruption by the leftist movement in power for two decades, but [President Nicolas] Maduro says US economic sanctions are the cause.

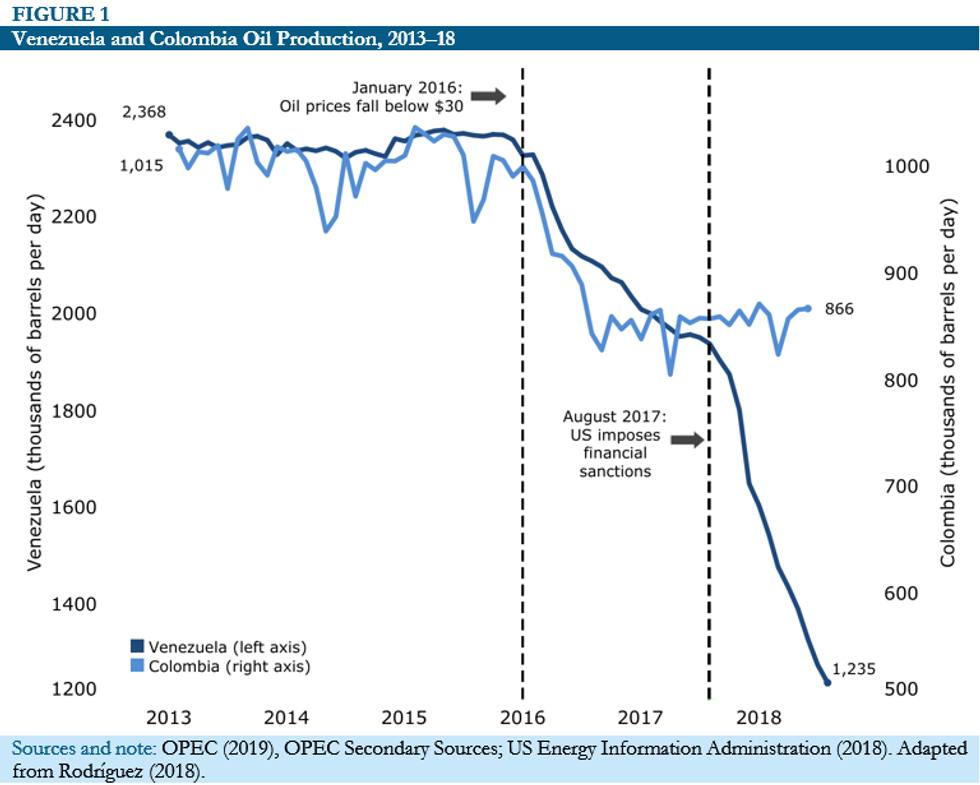

I asked why the piece made no mention of a study (CEPR, 4/25/19) released a month earlier by economists Mark Weisbrot and Jeffrey Sachs, which directly linked US sanctions to 40,000 deaths in Venezuela since August of 2017.

Her reply to me on May 23 was quite telling:

I was not aware of that study, but am now and will bear in mind.

It would indeed have been impossible for a Reuters reporter to be aware of the study if they depended only on Reuters articles to keep informed. The news agency hadn't mentioned the study since it was released, never mind written an article about it.

I asked a contact I have at Reuters about this, and he was also surprised that Reuters hadn't even mentioned the study. He suggested I query some of Reuters' Venezuela-based reporters, which I did a few days later.

In my email to them, I passed along a list of news articles since August 2017, when Trump first dramatically intensified economic sanctions, that described worsening economic conditions. I also noted that though the Sachs/Weisbrot study was ignored by Reuters, it had been intensely debated in public by Venezuelan opposition economists (i.e., the kind of people Reuters and other Western media actually pay attention to on Venezuela).

The Brookings Institution published a few rebuttals to the study (here and here), which I also pointed out to Reuters. The objections Brookings made were essentially already addressed by Weisbrot and Sachs in response to other critics.

On June 9, Reuters finally mentioned the study, at the end of an article by Nebehay, who is based in Geneva:

One study in April, co-authored by US economists Jeffrey Sachs and Mark Weisbrot, blamed sanctions for causing more deaths and disproportionately hitting the most vulnerable.

"We find that the sanctions have inflicted, and increasingly inflict, very serious harm to human life and health, including an estimated more than 40,000 deaths from 2017-2018," they said, arguing they were illegal under international law.

Nevertheless, since the day Nebehay replied to me, Reuters has continued to portray the severe impact of US sanctions as an allegation that only Maduro and other Venezuelan officials have made. It was even done by Reuters in an article published June 10, the day after the wire service finally mentioned the study:

The government of President Nicolas Maduro says Venezuela's economic problems are caused by US sanctions that have crippled the OPEC member's export earnings and blocked it from borrowing from abroad.

Other instances of Reuters representing the idea that US sanctions work as they are intended to do--in other words, that they hurt the Venezuelan economy--as an allegation made by Maduro or his government:

- "He [President Maduro] says the country's economic problems are the result of an 'economic war' led by his political adversaries with the help of Washington." (5/23/19)

- "Maduro, who maintains control over state institutions, calls Guaido a puppet of Washington and blames US sanctions for a hyperinflationary economic meltdown and humanitarian crisis." (5/26/19; repeated almost verbatim, 5/28/19)

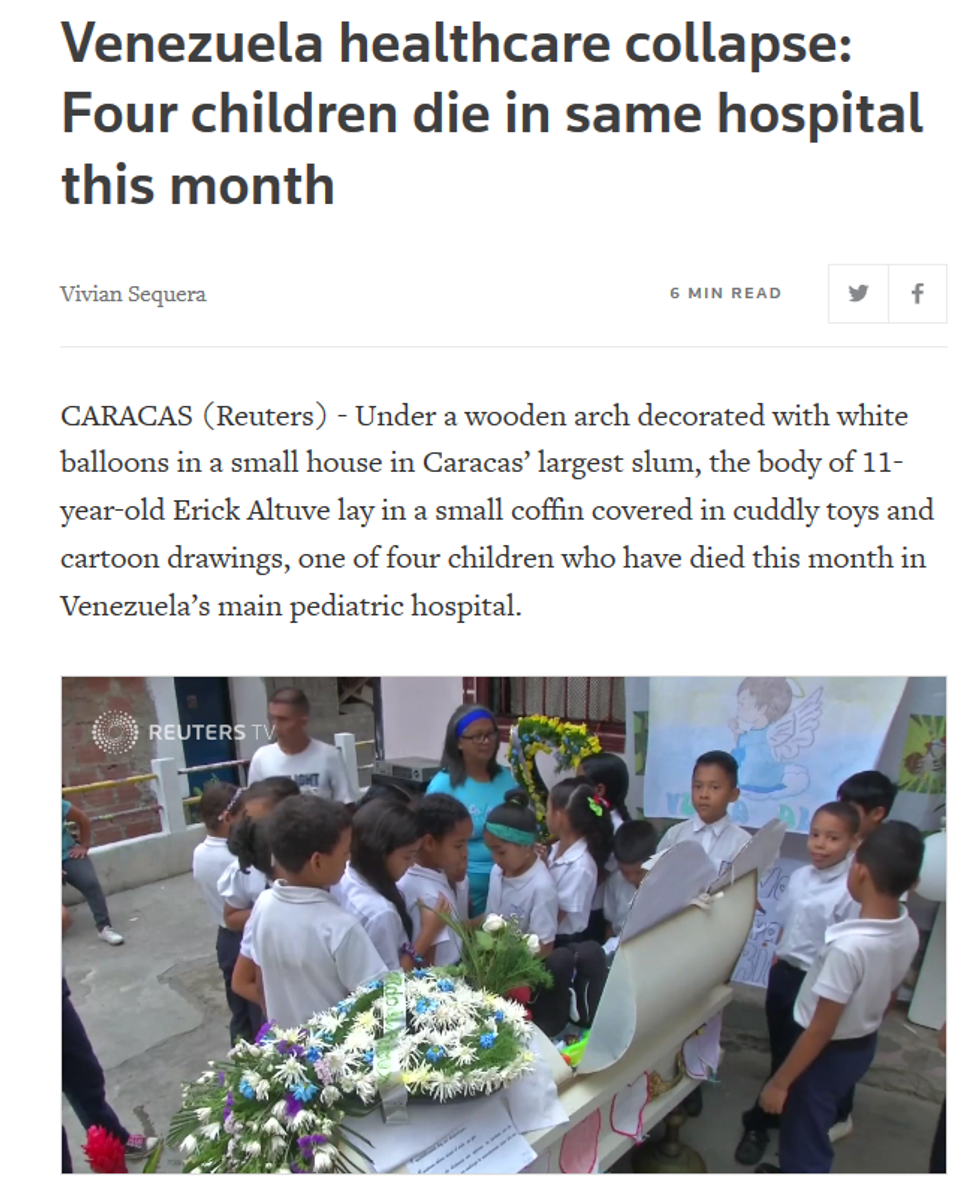

- "Maduro's government, however, says US-imposed sanctions were responsible for the children's deaths, by freezing funds allocated to buy medicine and send the children to Italy for treatment under the 2010 agreement." (6/1/19)

- "Maduro blames the situation on an 'economic war' waged by his political adversaries as well as US sanctions that have hobbled the oil industry and prevented his government from borrowing abroad." (6/7/19)

- "Maduro says Venezuela is victim of an 'economic war' led by the opposition with the help of Washington, which has levied several rounds of sanctions against his government." (6/7/19)

Two recent articles by Reuters, however, stated the obvious about the most recent US sanctions that were implemented in 2019:

- "Venezuela is in the midst of a years-long economic and humanitarian crisis that has deepened since the United States imposed sanctions on the country's oil industry in January as part of an effort to oust Socialist President Nicolas Maduro in favor of opposition leader Juan Guaido." (6/7/19)

- "Venezuela's oil exports dropped 17 percent in May because of the sanctions." (6/6/19)

But the study Reuters belatedly mentioned shows that US sanctions have been devastating to Venezuela's economy, and seriously aggravating the humanitarian crisis, since August 2017.

Apologists for Trump always rush to say that Venezuela's depression began years before Trump's sanctions--as if that made it acceptable to deliberately worsen a humanitarian crisis. To tweak an analogy Caitlin Johnstone used, think of a defense attorney saying, "Your Honor, I will show that the victim was already in intensive care when my client began to assault him."

Moreover, as Steve Ellner recently discussed, US support for an insurrectionist opposition in Venezuela goes back over a decade before the crisis, and was a factor in causing it. Economic sanctions Obama introduced in 2015 were also harmful--Weisbrot (The Hill, 11/6/16) in 2016 called them "ugly and belligerent enough to keep many investors from investing in Venezuela and to raise the country's cost of borrowing"--even before Trump's dramatic escalation of economic warfare that they paved the way for.

Putting aside a study by prominent US economists, the "Maduro says" formulation is also inexcusable because US Sen. Marco Rubio, who has been widely reported as a major influence on Trump's Venezuela policy, gleefully tweeted on May 16 that Maduro "can't access funds to rebuild electric grid."

Rubio didn't pretend he was referring to an imaginary electric grid used exclusively by Maduro. Reuters (5/30/19) has itself referred to Rubio as the "leading voice in the crafting of President Donald Trump's Venezuela policy," in a lengthy piece about US sanctions that said absolutely nothing about their impact on the general population, implying throughout that sanctions only impacted Maduro and other officials. ("Being blacklisted also crimps the lifestyle of Venezuelan officials' families," Reuters reported.)

My fellow FAIR contributor, Alan MacLeod, interviewed many Venezuela-based journalists for his book Bad News From Venezuela. He wrote last year (FAIR.org, 5/24/18):

Media copy and paste from news organizations like Reuters and Associated Press, which themselves employ many cheaper local journalists.

In Venezuela, these journalists are not neutral actors, but come from the highly partisan local media, affiliated with the opposition, leading to a situation where Western newsrooms see themselves as an ideological spearhead against Maduro, "the resistance" to the government.

Even worse than being the "resistance" to Maduro is that Reuters has often made itself the "assistance" to politicians like Rubio, who are vicious enough to celebrate the economic strangulation of millions of people.

Reuters may carry on as if it had never reported the study by Weisbrot and Sachs. Western media outlets are perfectly willing to ignore their own reporting when it suits powerful interests (Extra! Update, 10/02). It is therefore up to all of us to not be passive consumers of news, and continually bear in mind that the news we are getting about official enemies may be less than half the story.