SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

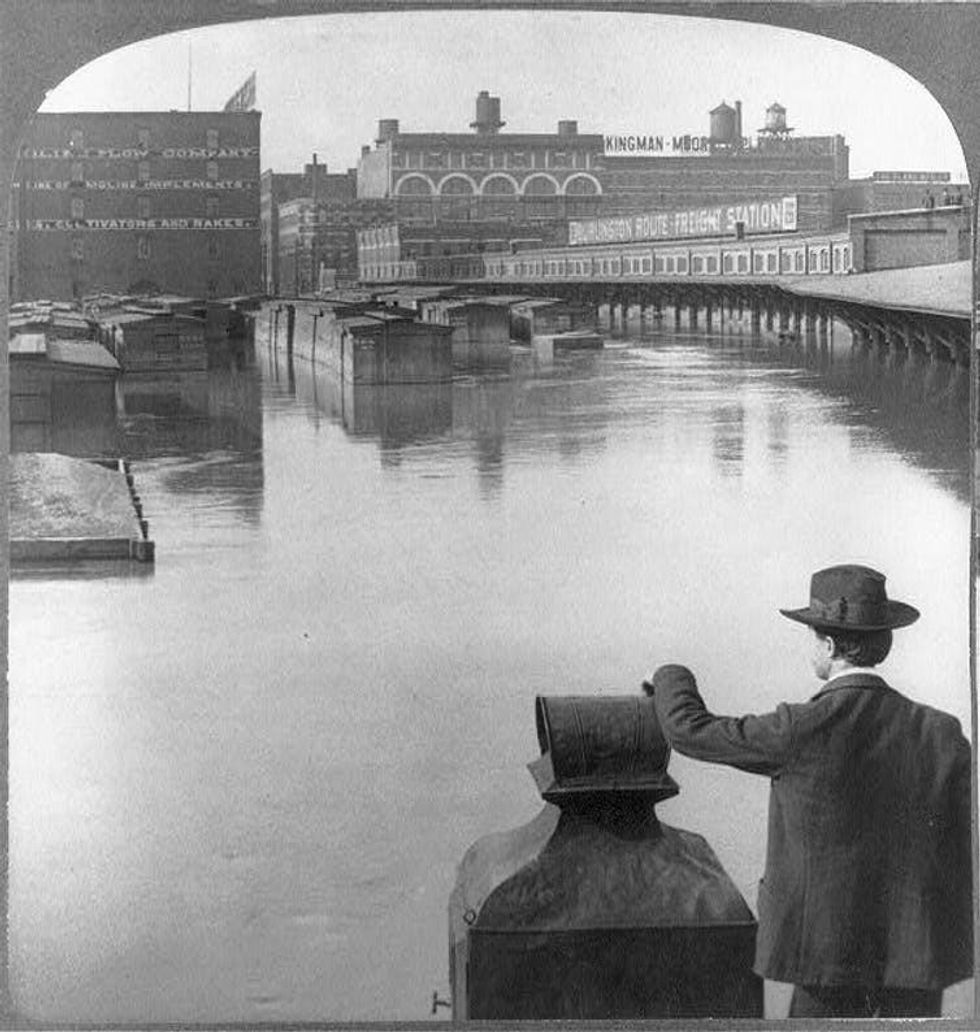

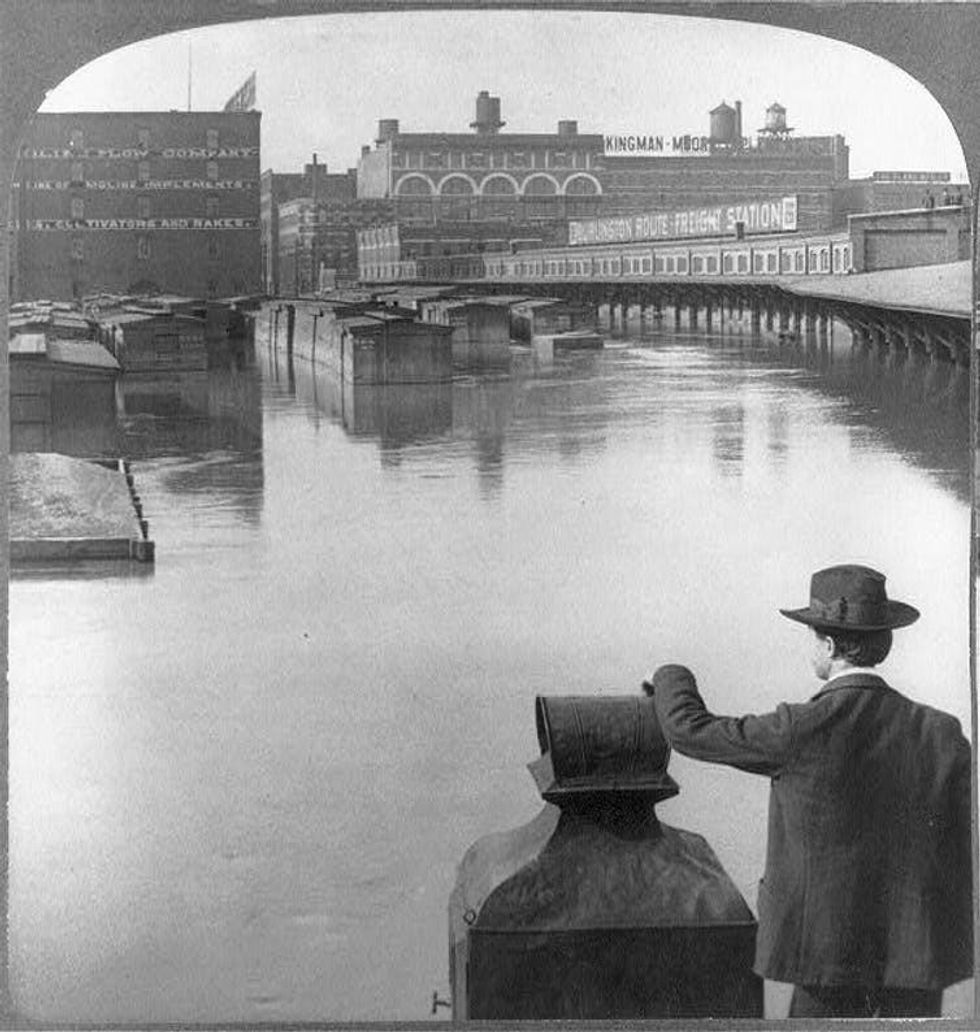

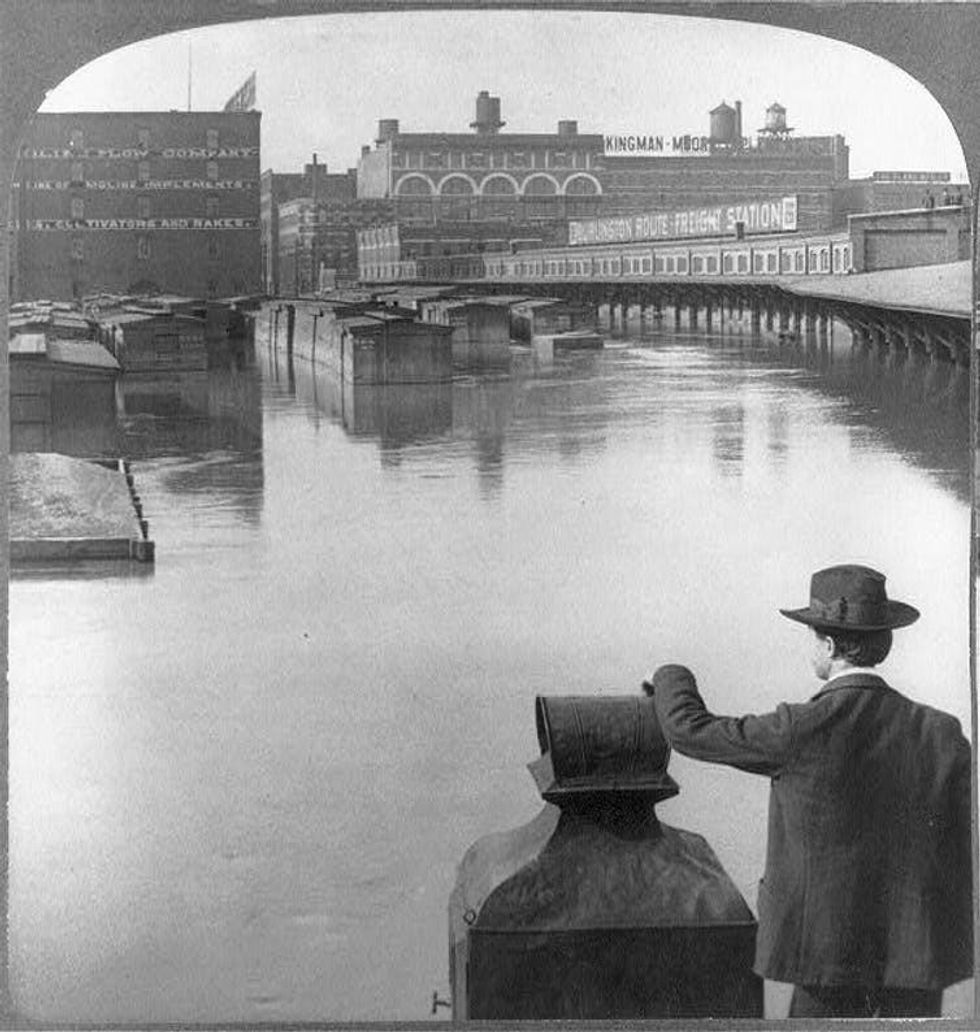

Grape-Bollin-Schwartz Levee overtops in numerous areas June 27, 2011. The road that crosses the railroad and goes to the levee is overtopping and eroding. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers photo by Susan Abbott via flickr/cc)

New Orleans averted disaster this month when tropical storm Barry delivered less rain in the Crescent City than forecasters originally feared. But Barry's slog through Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee and Missouri is just the latest event in a year that has tested levees across the central U.S.

Many U.S. cities rely on levees for protection from floods. There are more than 100,000 miles of levees nationwide, in all 50 states and one of every five counties. Most of them seriously need repair: Levees received a D on the American Society of Civil Engineers' 2018 national infrastructure report card.

Levees shield farms and towns from flooding, but they also create risk. When rivers rise, they can't naturally spread out in the floodplain as they did in the pre-flood control era. Instead, they flow harder and faster and send more water downstream.

And climate models show that flood risks are increasing. During this year's unusually wet winter and spring, dozens of levees on the Missouri, Mississippi and Arkansas rivers were overtopped or breached by floodwaters. Across the central U.S., rivers are becoming increasingly hard to control.

In my book, "A River in the City of Fountains," I describe the complexities of flood control in Kansas City, which sits at the junction of the Missouri and Kansas rivers.

The Missouri, the larger of these two, is America's longest river, rising in Montana's Rocky Mountains and flowing east and south for 2,341 miles until it joins the Mississippi River north of St. Louis. Historically it was wide and shallow, full of sand bars and snags that created challenges for steamboats.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Kansas City business leaders began lobbying for federal navigation subsidies to counter the influence of the railroads. Until the river could be narrowed and deepened, navigation was unreliable. And without levees, industry in the floodplain was at risk.

In 1944 they got their wish when Congress passed the Flood Control Act, which authorized construction of dozens of dams nationwide. One section of the bill, the Missouri Basin Plan, sought to convert the entire Missouri into what historian Donald Worster calls an "ornate hydraulic regime," with five upstream dams for hydroelectric power, irrigation and recreation, as well as levees and a navigable barge channel from Sioux City to St. Louis.

Over the next decade engineers built levees and straightened and dredged the river channel. Upstream dams curbed the Missouri's spring rise. In August 1955, Life Magazine reported that "U.S. engineers have finally clinched their victory over the rampaging Missouri River. Flood control ... is already bringing prosperity to the valley it drains."

Today Kansas City and many other U.S. river towns are fortified behind levees and floodwalls, but faith in the idea of engineered flood control is starting to erode.

Disastrous Midwest flooding in the summer of 1993, which killed 50 people and caused US$15 billion in damages, showed the limitations of this strategy. Floodwaters rose to unprecedented levels, eventually breaching or overtopping more than 1,000 levees.

After the waters ebbed, federal and state officials paid to move some homes and communities off floodplains to higher ground. However, this trend quickly reversed. By 2008, Missouri had authorized more than $2 billion of new development in zones that were flooded in 1993.

For their part, many scientists and engineers have found that levees can exacerbate floods by pushing river waters to new heights. One 2018 study estimated that about 75% of increases in the magnitude of 100-year floods on the lower Mississippi River over the past 500 years could be attributed to river engineering.

What about commercial benefits from channeling rivers? Kansas City is still an economic hub, but railroads and highways have been more important than barges. The Missouri carries only a fraction of the tonnage shipped on other navigable rivers, such as the Mississippi, even though its channel has been expensively built and maintained for over 100 years.

Levees also constrain cities' relationships with rivers, walling off any connections for purposes other than commerce. Author William Least Heat-Moon captured this paradox when he traveled across the U.S. by boat in the late 1990s and observed that "Kansas City, born of the Missouri, has turned away from its great genetrix more than almost any other river city in America."

More recently, however, Kansas City has begun to remember its interest and love for the Missouri. Riverside development and public spaces are fostering new physical and cultural interfaces with the river.

In my view, this year's floods should lead to more of this kind of rethinking. River towns can start by restricting floodplain development so that people and property will not be in harm's way. This will create space for rivers to spill over in flood season, reducing risks downstream. Proposals to raise and improve levees should be required to take climate change and related flooding risks into account.

Davenport, Iowa has embraced this approach. With a population of over 102,000, it is the largest U.S. river city without levees or a permanent floodwall. Instead Davenport has emphasized adapting to flooding by increasing public green spaces in the flood zone and elevating buildings that flank the Mississippi River.

Kansas City and other towns could advance this discussion by moving beyond strictly commercial visions of their waterways and considering this question: What does a healthy river of the future look like?

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

New Orleans averted disaster this month when tropical storm Barry delivered less rain in the Crescent City than forecasters originally feared. But Barry's slog through Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee and Missouri is just the latest event in a year that has tested levees across the central U.S.

Many U.S. cities rely on levees for protection from floods. There are more than 100,000 miles of levees nationwide, in all 50 states and one of every five counties. Most of them seriously need repair: Levees received a D on the American Society of Civil Engineers' 2018 national infrastructure report card.

Levees shield farms and towns from flooding, but they also create risk. When rivers rise, they can't naturally spread out in the floodplain as they did in the pre-flood control era. Instead, they flow harder and faster and send more water downstream.

And climate models show that flood risks are increasing. During this year's unusually wet winter and spring, dozens of levees on the Missouri, Mississippi and Arkansas rivers were overtopped or breached by floodwaters. Across the central U.S., rivers are becoming increasingly hard to control.

In my book, "A River in the City of Fountains," I describe the complexities of flood control in Kansas City, which sits at the junction of the Missouri and Kansas rivers.

The Missouri, the larger of these two, is America's longest river, rising in Montana's Rocky Mountains and flowing east and south for 2,341 miles until it joins the Mississippi River north of St. Louis. Historically it was wide and shallow, full of sand bars and snags that created challenges for steamboats.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Kansas City business leaders began lobbying for federal navigation subsidies to counter the influence of the railroads. Until the river could be narrowed and deepened, navigation was unreliable. And without levees, industry in the floodplain was at risk.

In 1944 they got their wish when Congress passed the Flood Control Act, which authorized construction of dozens of dams nationwide. One section of the bill, the Missouri Basin Plan, sought to convert the entire Missouri into what historian Donald Worster calls an "ornate hydraulic regime," with five upstream dams for hydroelectric power, irrigation and recreation, as well as levees and a navigable barge channel from Sioux City to St. Louis.

Over the next decade engineers built levees and straightened and dredged the river channel. Upstream dams curbed the Missouri's spring rise. In August 1955, Life Magazine reported that "U.S. engineers have finally clinched their victory over the rampaging Missouri River. Flood control ... is already bringing prosperity to the valley it drains."

Today Kansas City and many other U.S. river towns are fortified behind levees and floodwalls, but faith in the idea of engineered flood control is starting to erode.

Disastrous Midwest flooding in the summer of 1993, which killed 50 people and caused US$15 billion in damages, showed the limitations of this strategy. Floodwaters rose to unprecedented levels, eventually breaching or overtopping more than 1,000 levees.

After the waters ebbed, federal and state officials paid to move some homes and communities off floodplains to higher ground. However, this trend quickly reversed. By 2008, Missouri had authorized more than $2 billion of new development in zones that were flooded in 1993.

For their part, many scientists and engineers have found that levees can exacerbate floods by pushing river waters to new heights. One 2018 study estimated that about 75% of increases in the magnitude of 100-year floods on the lower Mississippi River over the past 500 years could be attributed to river engineering.

What about commercial benefits from channeling rivers? Kansas City is still an economic hub, but railroads and highways have been more important than barges. The Missouri carries only a fraction of the tonnage shipped on other navigable rivers, such as the Mississippi, even though its channel has been expensively built and maintained for over 100 years.

Levees also constrain cities' relationships with rivers, walling off any connections for purposes other than commerce. Author William Least Heat-Moon captured this paradox when he traveled across the U.S. by boat in the late 1990s and observed that "Kansas City, born of the Missouri, has turned away from its great genetrix more than almost any other river city in America."

More recently, however, Kansas City has begun to remember its interest and love for the Missouri. Riverside development and public spaces are fostering new physical and cultural interfaces with the river.

In my view, this year's floods should lead to more of this kind of rethinking. River towns can start by restricting floodplain development so that people and property will not be in harm's way. This will create space for rivers to spill over in flood season, reducing risks downstream. Proposals to raise and improve levees should be required to take climate change and related flooding risks into account.

Davenport, Iowa has embraced this approach. With a population of over 102,000, it is the largest U.S. river city without levees or a permanent floodwall. Instead Davenport has emphasized adapting to flooding by increasing public green spaces in the flood zone and elevating buildings that flank the Mississippi River.

Kansas City and other towns could advance this discussion by moving beyond strictly commercial visions of their waterways and considering this question: What does a healthy river of the future look like?

New Orleans averted disaster this month when tropical storm Barry delivered less rain in the Crescent City than forecasters originally feared. But Barry's slog through Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee and Missouri is just the latest event in a year that has tested levees across the central U.S.

Many U.S. cities rely on levees for protection from floods. There are more than 100,000 miles of levees nationwide, in all 50 states and one of every five counties. Most of them seriously need repair: Levees received a D on the American Society of Civil Engineers' 2018 national infrastructure report card.

Levees shield farms and towns from flooding, but they also create risk. When rivers rise, they can't naturally spread out in the floodplain as they did in the pre-flood control era. Instead, they flow harder and faster and send more water downstream.

And climate models show that flood risks are increasing. During this year's unusually wet winter and spring, dozens of levees on the Missouri, Mississippi and Arkansas rivers were overtopped or breached by floodwaters. Across the central U.S., rivers are becoming increasingly hard to control.

In my book, "A River in the City of Fountains," I describe the complexities of flood control in Kansas City, which sits at the junction of the Missouri and Kansas rivers.

The Missouri, the larger of these two, is America's longest river, rising in Montana's Rocky Mountains and flowing east and south for 2,341 miles until it joins the Mississippi River north of St. Louis. Historically it was wide and shallow, full of sand bars and snags that created challenges for steamboats.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Kansas City business leaders began lobbying for federal navigation subsidies to counter the influence of the railroads. Until the river could be narrowed and deepened, navigation was unreliable. And without levees, industry in the floodplain was at risk.

In 1944 they got their wish when Congress passed the Flood Control Act, which authorized construction of dozens of dams nationwide. One section of the bill, the Missouri Basin Plan, sought to convert the entire Missouri into what historian Donald Worster calls an "ornate hydraulic regime," with five upstream dams for hydroelectric power, irrigation and recreation, as well as levees and a navigable barge channel from Sioux City to St. Louis.

Over the next decade engineers built levees and straightened and dredged the river channel. Upstream dams curbed the Missouri's spring rise. In August 1955, Life Magazine reported that "U.S. engineers have finally clinched their victory over the rampaging Missouri River. Flood control ... is already bringing prosperity to the valley it drains."

Today Kansas City and many other U.S. river towns are fortified behind levees and floodwalls, but faith in the idea of engineered flood control is starting to erode.

Disastrous Midwest flooding in the summer of 1993, which killed 50 people and caused US$15 billion in damages, showed the limitations of this strategy. Floodwaters rose to unprecedented levels, eventually breaching or overtopping more than 1,000 levees.

After the waters ebbed, federal and state officials paid to move some homes and communities off floodplains to higher ground. However, this trend quickly reversed. By 2008, Missouri had authorized more than $2 billion of new development in zones that were flooded in 1993.

For their part, many scientists and engineers have found that levees can exacerbate floods by pushing river waters to new heights. One 2018 study estimated that about 75% of increases in the magnitude of 100-year floods on the lower Mississippi River over the past 500 years could be attributed to river engineering.

What about commercial benefits from channeling rivers? Kansas City is still an economic hub, but railroads and highways have been more important than barges. The Missouri carries only a fraction of the tonnage shipped on other navigable rivers, such as the Mississippi, even though its channel has been expensively built and maintained for over 100 years.

Levees also constrain cities' relationships with rivers, walling off any connections for purposes other than commerce. Author William Least Heat-Moon captured this paradox when he traveled across the U.S. by boat in the late 1990s and observed that "Kansas City, born of the Missouri, has turned away from its great genetrix more than almost any other river city in America."

More recently, however, Kansas City has begun to remember its interest and love for the Missouri. Riverside development and public spaces are fostering new physical and cultural interfaces with the river.

In my view, this year's floods should lead to more of this kind of rethinking. River towns can start by restricting floodplain development so that people and property will not be in harm's way. This will create space for rivers to spill over in flood season, reducing risks downstream. Proposals to raise and improve levees should be required to take climate change and related flooding risks into account.

Davenport, Iowa has embraced this approach. With a population of over 102,000, it is the largest U.S. river city without levees or a permanent floodwall. Instead Davenport has emphasized adapting to flooding by increasing public green spaces in the flood zone and elevating buildings that flank the Mississippi River.

Kansas City and other towns could advance this discussion by moving beyond strictly commercial visions of their waterways and considering this question: What does a healthy river of the future look like?