SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"The situation we now find ourselves in of spiraling global economic injustice and environmental collapse," the author writes, "didn't just happen." (Photo: teigan/flickr/cc)

The British Labour Party's International Social Forum at SOAS last weekend explored many of the same issues as ourEconomy's new 'Decolonising the economy' series. It brought together an impressive line-up of speakers - including Jayati Ghosh, Gyekye Tanoh, Ann Pettifor and Yanis Varoufakis - with a wide-ranging group of delegates around panels on the climate crisis, global finance, migration and trade. The question on the table was one that couldn't be more timely, given the intersecting crises of global inequality and ecological collapse: 'What would a new internationalism look like?'

The forum marked the launch of a 12-month programme to answer that question and develop an agenda to transform our economic structures to serve people and planet. Here I will attempt to bring together several strands of thought that were pursued and sketch and first outline of what that agenda might look like. I hope the participants will forgive any bungling of their arguments or the tangents that they inspired me to follow. One last disclaimer - the ideas presented here are not Labour policy and may never be - they are only examples the kinds of thinking taking place at the forum.

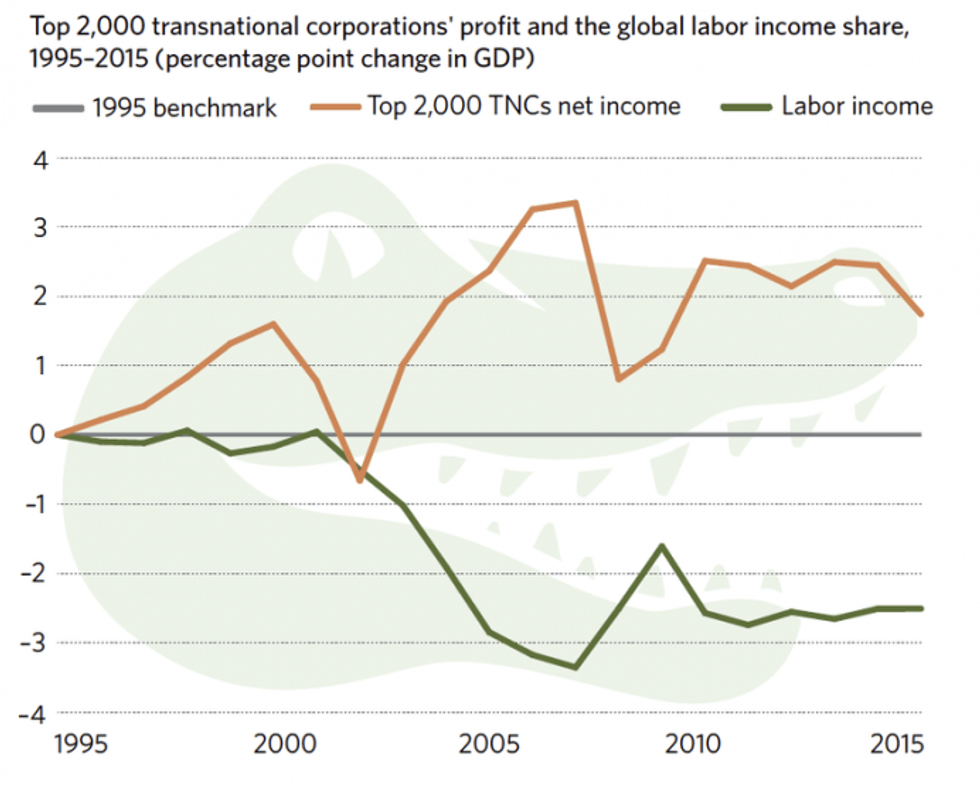

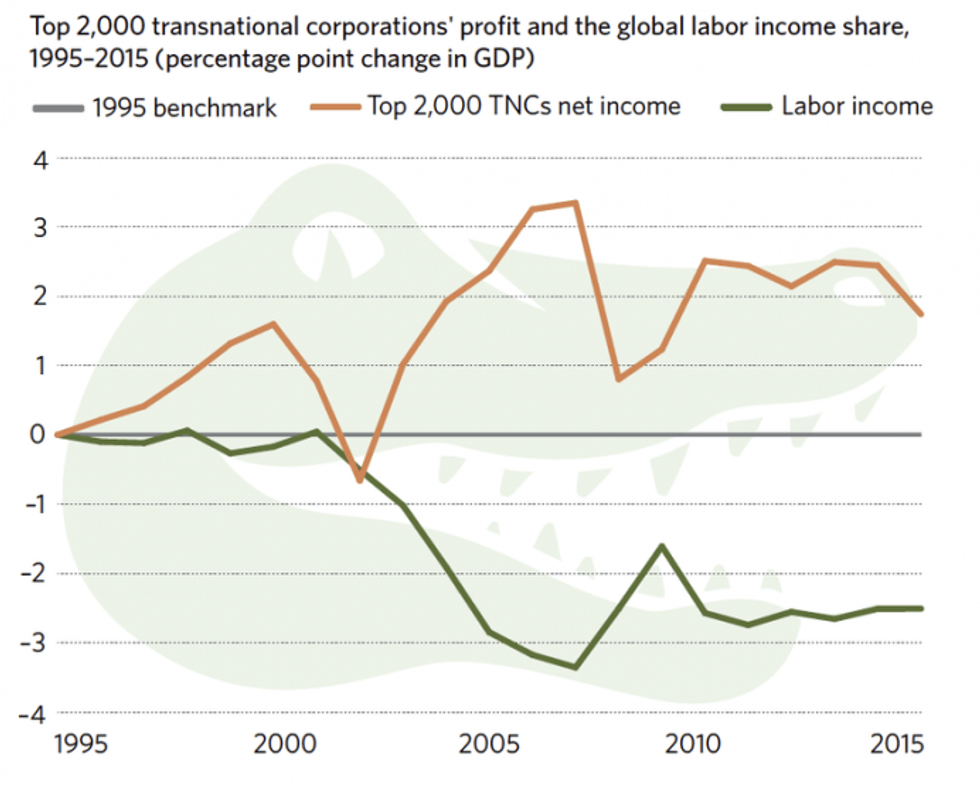

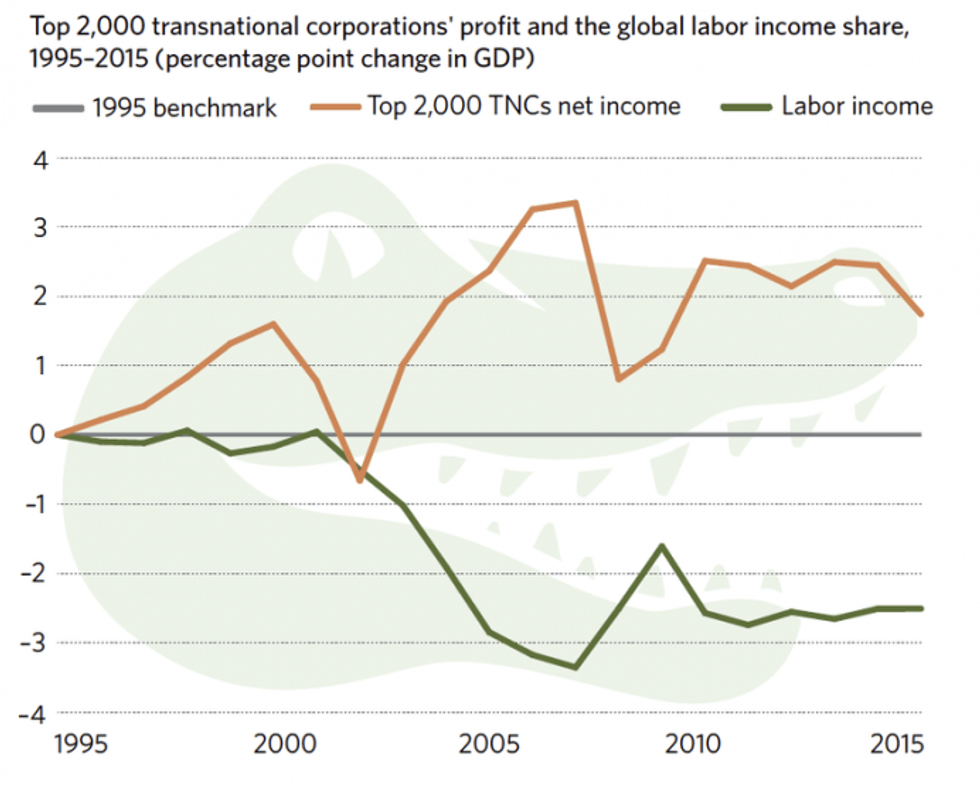

The situation we now find ourselves in of spiraling global economic injustice and environmental collapse didn't just happen. It was a result of a class struggle that led from the late 1970s to a restructuring of the global economy and society more widely in the interests of multinational corporations and against the interests of planet earth and almost everyone who lives on it. Transnational institutions like the WTO, World Bank and IMF were created or redesigned to push through an agenda of privatisation, deregulation, financialisation and 'hyperglobalisation'. This has led to wealth - much of it created through resource extraction and the super-exploitation of workers in the global south - being distributed in an increasingly unequal way - as shown by the 'crocodile graph' below, presented by UNCTAD's Richard Kozul-Wright.

Let's start with the 'how' before getting to the 'what'. Tackling climate change and pursing global economic justice are hard for one country to do alone. Just as transnational bodies were created or reformed to roll out the neoliberal agenda and the 'Washington Consensus', progressive governments pushed by social movements need to forge alliances and create new transnational institutions to implement a new agenda. Unlike the current institutions, they should be democratic, with votes being equally distributed among members.

In the meantime, countries like the UK and the US do have disproportionate power in the global arena due to their imperial pasts and presents, and if progressive forces manage to get into power in those countries they can caucus with countries of the global south and use their votes in the existing transnational institutions in a solidary manner.

What kind of agenda should these new institutions be pushing? It would need to take a joined-up approach on several fronts.

Key among these new institutions would be transnational unions engaged in transnational collective bargaining. These would take a new form, to include precarious and causal workers, those who cannot work and those who are unemployed, as well as those in secure employment. National unions should also be reformed and expanded to represent such constituencies, and to embed internationalism and anti-racism at their core. What would these new and reformed unions be demanding? A global living wage and global labour rights, so that workers and citizens from the global north are not benefiting from the super-exploitation of workers from the global south.

The neoliberal agenda was about privatisation and commodification - transferring the ownership and control of resources to corporations. The new internationalist agenda would conversely be about deprivatisation, decommodification and democratisation - transferring essential resources like land, water and energy to public sectors to be used not for profit but to benefit communities in a way that is compatible with the health of the natural environment. This would redistribute pilfered resources back to the global south and free up capacity to invest in the green transition.

A word of caution: just because something is publicly owned doesn't automatically mean it will work in the public interest. The control of these resources should therefore be democratic and abide by the principle of subsidiarity - decisions should be made by the smallest political unit capable of carrying them out. Many decisions about resource use could be made at the community level, while others could be made at a national or global level - for example when it comes to massive public investment in green infrastructure (Varoufakis suggests 5% of global GDP).

Currently, the rules of trade and investment - enforced by the WTO and in free-trade agreements - are rigged in favor of corporations based in the global north. New rules would allow the kinds of changes of ownership described above, and get rid of investor protections that allow corporations to prevent governments from implementing measures on behalf of their citizens. They would allow lower-income countries to protect their infant industries while dismantling the rich-country protectionism of intellectual property regimes that mean people can't afford access to medicine. Social clauses or human rights obligations could be built into trade agreements.

Meanwhile, the dollar could be replaced as the international reserve currency with an international reserve currency, or countries could use their own currencies for bi-lateral trade - helping to re-balance global economic power.

Most people don't need reminding of the dangers posed by a humongous and bezerk financial sector. Proposals included the breaking up of too-big-to-fail banks, regulation of the shadow baking sector, and equity ratios of 15-18%. Kavaljit Singh argued that lower-income countries be able to use capital controls to protect their economies from speculative capital flows - something that should be the responsibility of both source and recipient countries.

Yanis Varoufakis and his colleagues propose reviving Keynes' idea of an international clearing union that would help keep the global economy stable by taxing both deficits and surpluses - with the money raised being channeled into a global green new deal.

As with other resources, ownership is also an issue. Public finance needs to be available to make a green transition a reality, as private finance has proven unfit for the task. As with other publicly owned resources, though, public banks need to be democratised in order to work in the public interest.

Some have claimed that the huge multinationals are on a 'tax strike', so little tax do they pay. International co-operation is needed to make sure corporations pay their fair share. Minimum corporate tax rates and global wealth taxes were among the options discussed. Another important idea floated was a unitary tax on multinationals. Currently, corporations use all kinds of accounting tricks to move money between subsidiaries so they can avoid paying tax. Developing countries lose $3 billion per day through such creative accounting. With a unitary tax, a global minimum effective corporate-tax rate of between 20 and 25 per cent would be levied. The proceeds would be allocated among governments according to factors such as the company's sales, employment and number of digital users in each country--rather than on where multinationals decide to locate their operations and intellectual property.

Humans may have been on the move for most of our history, but much modern migration is the result of an economic system that creates dispossession and displacement. This same economic system - one which is structured through racism - then constitutes those who experience that dispossession as migrants, without rights and subject to the deepest forms of exploitation. A new internationalist vision needs to rest on a reframing of the problem - the problem we have is not migrants but borders.

As Rafeef Ziadah pointed out, we already have open borders - open to capital and open to those who can afford to buy citizenship. Why, then, not call for open borders for all? The question then becomes how to create the conditions by which open borders become possible - so that people don't have to leave their homes in the first place if they don't want to. That means decolonising the global economy - partly by pursuing the changes in ownership, labour, trade, finance and tax regimes outlined above, and by developing appropriate foreign and development policy. Meanwhile, there are things that individual countries can do - in the UK, this means dismantling the hostile environment, and teaching the realities of empire in schools.

You may at this point be thinking that it's all well and good to have a global transformation wish-list, but how an earth are we going to get there given where we now are? Don't forget that neoliberal globalisation was also at one point a utopian fringe project. But the neoliberal movement gathered intellectuals, established transnational organisations and mobilised politicians and publics to map out a vision and roll it out across the globe. Perhaps it's time we learned from them.

The Labour Party's International Social Forum kickstarted a much needed debate about the global economy and global justice. Now the task is to ensure that these words translate into a bold policy agenda, and a movement to match.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

The British Labour Party's International Social Forum at SOAS last weekend explored many of the same issues as ourEconomy's new 'Decolonising the economy' series. It brought together an impressive line-up of speakers - including Jayati Ghosh, Gyekye Tanoh, Ann Pettifor and Yanis Varoufakis - with a wide-ranging group of delegates around panels on the climate crisis, global finance, migration and trade. The question on the table was one that couldn't be more timely, given the intersecting crises of global inequality and ecological collapse: 'What would a new internationalism look like?'

The forum marked the launch of a 12-month programme to answer that question and develop an agenda to transform our economic structures to serve people and planet. Here I will attempt to bring together several strands of thought that were pursued and sketch and first outline of what that agenda might look like. I hope the participants will forgive any bungling of their arguments or the tangents that they inspired me to follow. One last disclaimer - the ideas presented here are not Labour policy and may never be - they are only examples the kinds of thinking taking place at the forum.

The situation we now find ourselves in of spiraling global economic injustice and environmental collapse didn't just happen. It was a result of a class struggle that led from the late 1970s to a restructuring of the global economy and society more widely in the interests of multinational corporations and against the interests of planet earth and almost everyone who lives on it. Transnational institutions like the WTO, World Bank and IMF were created or redesigned to push through an agenda of privatisation, deregulation, financialisation and 'hyperglobalisation'. This has led to wealth - much of it created through resource extraction and the super-exploitation of workers in the global south - being distributed in an increasingly unequal way - as shown by the 'crocodile graph' below, presented by UNCTAD's Richard Kozul-Wright.

Let's start with the 'how' before getting to the 'what'. Tackling climate change and pursing global economic justice are hard for one country to do alone. Just as transnational bodies were created or reformed to roll out the neoliberal agenda and the 'Washington Consensus', progressive governments pushed by social movements need to forge alliances and create new transnational institutions to implement a new agenda. Unlike the current institutions, they should be democratic, with votes being equally distributed among members.

In the meantime, countries like the UK and the US do have disproportionate power in the global arena due to their imperial pasts and presents, and if progressive forces manage to get into power in those countries they can caucus with countries of the global south and use their votes in the existing transnational institutions in a solidary manner.

What kind of agenda should these new institutions be pushing? It would need to take a joined-up approach on several fronts.

Key among these new institutions would be transnational unions engaged in transnational collective bargaining. These would take a new form, to include precarious and causal workers, those who cannot work and those who are unemployed, as well as those in secure employment. National unions should also be reformed and expanded to represent such constituencies, and to embed internationalism and anti-racism at their core. What would these new and reformed unions be demanding? A global living wage and global labour rights, so that workers and citizens from the global north are not benefiting from the super-exploitation of workers from the global south.

The neoliberal agenda was about privatisation and commodification - transferring the ownership and control of resources to corporations. The new internationalist agenda would conversely be about deprivatisation, decommodification and democratisation - transferring essential resources like land, water and energy to public sectors to be used not for profit but to benefit communities in a way that is compatible with the health of the natural environment. This would redistribute pilfered resources back to the global south and free up capacity to invest in the green transition.

A word of caution: just because something is publicly owned doesn't automatically mean it will work in the public interest. The control of these resources should therefore be democratic and abide by the principle of subsidiarity - decisions should be made by the smallest political unit capable of carrying them out. Many decisions about resource use could be made at the community level, while others could be made at a national or global level - for example when it comes to massive public investment in green infrastructure (Varoufakis suggests 5% of global GDP).

Currently, the rules of trade and investment - enforced by the WTO and in free-trade agreements - are rigged in favor of corporations based in the global north. New rules would allow the kinds of changes of ownership described above, and get rid of investor protections that allow corporations to prevent governments from implementing measures on behalf of their citizens. They would allow lower-income countries to protect their infant industries while dismantling the rich-country protectionism of intellectual property regimes that mean people can't afford access to medicine. Social clauses or human rights obligations could be built into trade agreements.

Meanwhile, the dollar could be replaced as the international reserve currency with an international reserve currency, or countries could use their own currencies for bi-lateral trade - helping to re-balance global economic power.

Most people don't need reminding of the dangers posed by a humongous and bezerk financial sector. Proposals included the breaking up of too-big-to-fail banks, regulation of the shadow baking sector, and equity ratios of 15-18%. Kavaljit Singh argued that lower-income countries be able to use capital controls to protect their economies from speculative capital flows - something that should be the responsibility of both source and recipient countries.

Yanis Varoufakis and his colleagues propose reviving Keynes' idea of an international clearing union that would help keep the global economy stable by taxing both deficits and surpluses - with the money raised being channeled into a global green new deal.

As with other resources, ownership is also an issue. Public finance needs to be available to make a green transition a reality, as private finance has proven unfit for the task. As with other publicly owned resources, though, public banks need to be democratised in order to work in the public interest.

Some have claimed that the huge multinationals are on a 'tax strike', so little tax do they pay. International co-operation is needed to make sure corporations pay their fair share. Minimum corporate tax rates and global wealth taxes were among the options discussed. Another important idea floated was a unitary tax on multinationals. Currently, corporations use all kinds of accounting tricks to move money between subsidiaries so they can avoid paying tax. Developing countries lose $3 billion per day through such creative accounting. With a unitary tax, a global minimum effective corporate-tax rate of between 20 and 25 per cent would be levied. The proceeds would be allocated among governments according to factors such as the company's sales, employment and number of digital users in each country--rather than on where multinationals decide to locate their operations and intellectual property.

Humans may have been on the move for most of our history, but much modern migration is the result of an economic system that creates dispossession and displacement. This same economic system - one which is structured through racism - then constitutes those who experience that dispossession as migrants, without rights and subject to the deepest forms of exploitation. A new internationalist vision needs to rest on a reframing of the problem - the problem we have is not migrants but borders.

As Rafeef Ziadah pointed out, we already have open borders - open to capital and open to those who can afford to buy citizenship. Why, then, not call for open borders for all? The question then becomes how to create the conditions by which open borders become possible - so that people don't have to leave their homes in the first place if they don't want to. That means decolonising the global economy - partly by pursuing the changes in ownership, labour, trade, finance and tax regimes outlined above, and by developing appropriate foreign and development policy. Meanwhile, there are things that individual countries can do - in the UK, this means dismantling the hostile environment, and teaching the realities of empire in schools.

You may at this point be thinking that it's all well and good to have a global transformation wish-list, but how an earth are we going to get there given where we now are? Don't forget that neoliberal globalisation was also at one point a utopian fringe project. But the neoliberal movement gathered intellectuals, established transnational organisations and mobilised politicians and publics to map out a vision and roll it out across the globe. Perhaps it's time we learned from them.

The Labour Party's International Social Forum kickstarted a much needed debate about the global economy and global justice. Now the task is to ensure that these words translate into a bold policy agenda, and a movement to match.

The British Labour Party's International Social Forum at SOAS last weekend explored many of the same issues as ourEconomy's new 'Decolonising the economy' series. It brought together an impressive line-up of speakers - including Jayati Ghosh, Gyekye Tanoh, Ann Pettifor and Yanis Varoufakis - with a wide-ranging group of delegates around panels on the climate crisis, global finance, migration and trade. The question on the table was one that couldn't be more timely, given the intersecting crises of global inequality and ecological collapse: 'What would a new internationalism look like?'

The forum marked the launch of a 12-month programme to answer that question and develop an agenda to transform our economic structures to serve people and planet. Here I will attempt to bring together several strands of thought that were pursued and sketch and first outline of what that agenda might look like. I hope the participants will forgive any bungling of their arguments or the tangents that they inspired me to follow. One last disclaimer - the ideas presented here are not Labour policy and may never be - they are only examples the kinds of thinking taking place at the forum.

The situation we now find ourselves in of spiraling global economic injustice and environmental collapse didn't just happen. It was a result of a class struggle that led from the late 1970s to a restructuring of the global economy and society more widely in the interests of multinational corporations and against the interests of planet earth and almost everyone who lives on it. Transnational institutions like the WTO, World Bank and IMF were created or redesigned to push through an agenda of privatisation, deregulation, financialisation and 'hyperglobalisation'. This has led to wealth - much of it created through resource extraction and the super-exploitation of workers in the global south - being distributed in an increasingly unequal way - as shown by the 'crocodile graph' below, presented by UNCTAD's Richard Kozul-Wright.

Let's start with the 'how' before getting to the 'what'. Tackling climate change and pursing global economic justice are hard for one country to do alone. Just as transnational bodies were created or reformed to roll out the neoliberal agenda and the 'Washington Consensus', progressive governments pushed by social movements need to forge alliances and create new transnational institutions to implement a new agenda. Unlike the current institutions, they should be democratic, with votes being equally distributed among members.

In the meantime, countries like the UK and the US do have disproportionate power in the global arena due to their imperial pasts and presents, and if progressive forces manage to get into power in those countries they can caucus with countries of the global south and use their votes in the existing transnational institutions in a solidary manner.

What kind of agenda should these new institutions be pushing? It would need to take a joined-up approach on several fronts.

Key among these new institutions would be transnational unions engaged in transnational collective bargaining. These would take a new form, to include precarious and causal workers, those who cannot work and those who are unemployed, as well as those in secure employment. National unions should also be reformed and expanded to represent such constituencies, and to embed internationalism and anti-racism at their core. What would these new and reformed unions be demanding? A global living wage and global labour rights, so that workers and citizens from the global north are not benefiting from the super-exploitation of workers from the global south.

The neoliberal agenda was about privatisation and commodification - transferring the ownership and control of resources to corporations. The new internationalist agenda would conversely be about deprivatisation, decommodification and democratisation - transferring essential resources like land, water and energy to public sectors to be used not for profit but to benefit communities in a way that is compatible with the health of the natural environment. This would redistribute pilfered resources back to the global south and free up capacity to invest in the green transition.

A word of caution: just because something is publicly owned doesn't automatically mean it will work in the public interest. The control of these resources should therefore be democratic and abide by the principle of subsidiarity - decisions should be made by the smallest political unit capable of carrying them out. Many decisions about resource use could be made at the community level, while others could be made at a national or global level - for example when it comes to massive public investment in green infrastructure (Varoufakis suggests 5% of global GDP).

Currently, the rules of trade and investment - enforced by the WTO and in free-trade agreements - are rigged in favor of corporations based in the global north. New rules would allow the kinds of changes of ownership described above, and get rid of investor protections that allow corporations to prevent governments from implementing measures on behalf of their citizens. They would allow lower-income countries to protect their infant industries while dismantling the rich-country protectionism of intellectual property regimes that mean people can't afford access to medicine. Social clauses or human rights obligations could be built into trade agreements.

Meanwhile, the dollar could be replaced as the international reserve currency with an international reserve currency, or countries could use their own currencies for bi-lateral trade - helping to re-balance global economic power.

Most people don't need reminding of the dangers posed by a humongous and bezerk financial sector. Proposals included the breaking up of too-big-to-fail banks, regulation of the shadow baking sector, and equity ratios of 15-18%. Kavaljit Singh argued that lower-income countries be able to use capital controls to protect their economies from speculative capital flows - something that should be the responsibility of both source and recipient countries.

Yanis Varoufakis and his colleagues propose reviving Keynes' idea of an international clearing union that would help keep the global economy stable by taxing both deficits and surpluses - with the money raised being channeled into a global green new deal.

As with other resources, ownership is also an issue. Public finance needs to be available to make a green transition a reality, as private finance has proven unfit for the task. As with other publicly owned resources, though, public banks need to be democratised in order to work in the public interest.

Some have claimed that the huge multinationals are on a 'tax strike', so little tax do they pay. International co-operation is needed to make sure corporations pay their fair share. Minimum corporate tax rates and global wealth taxes were among the options discussed. Another important idea floated was a unitary tax on multinationals. Currently, corporations use all kinds of accounting tricks to move money between subsidiaries so they can avoid paying tax. Developing countries lose $3 billion per day through such creative accounting. With a unitary tax, a global minimum effective corporate-tax rate of between 20 and 25 per cent would be levied. The proceeds would be allocated among governments according to factors such as the company's sales, employment and number of digital users in each country--rather than on where multinationals decide to locate their operations and intellectual property.

Humans may have been on the move for most of our history, but much modern migration is the result of an economic system that creates dispossession and displacement. This same economic system - one which is structured through racism - then constitutes those who experience that dispossession as migrants, without rights and subject to the deepest forms of exploitation. A new internationalist vision needs to rest on a reframing of the problem - the problem we have is not migrants but borders.

As Rafeef Ziadah pointed out, we already have open borders - open to capital and open to those who can afford to buy citizenship. Why, then, not call for open borders for all? The question then becomes how to create the conditions by which open borders become possible - so that people don't have to leave their homes in the first place if they don't want to. That means decolonising the global economy - partly by pursuing the changes in ownership, labour, trade, finance and tax regimes outlined above, and by developing appropriate foreign and development policy. Meanwhile, there are things that individual countries can do - in the UK, this means dismantling the hostile environment, and teaching the realities of empire in schools.

You may at this point be thinking that it's all well and good to have a global transformation wish-list, but how an earth are we going to get there given where we now are? Don't forget that neoliberal globalisation was also at one point a utopian fringe project. But the neoliberal movement gathered intellectuals, established transnational organisations and mobilised politicians and publics to map out a vision and roll it out across the globe. Perhaps it's time we learned from them.

The Labour Party's International Social Forum kickstarted a much needed debate about the global economy and global justice. Now the task is to ensure that these words translate into a bold policy agenda, and a movement to match.