Protesters outside JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon's New York City home. (Photo: Make the Road New York)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Protesters outside JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon's New York City home. (Photo: Make the Road New York)

In June 2018, Kelly Leibold was among the many residents of Pine Island, Minnesota, caught by surprise when its city council passed a resolution supporting a for-profit prison company, Management & Training Corporation, that wanted to locate a detention facility for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

She responded by helping local residents organize a "No ICE in PI" campaign.

"I don't believe that a detention facility is morally correct," Leibold explains. "People all have immigrant lines in their family. I don't think a detention facility in Pine Island will say good things about our community."

She and about three dozen other activists organized via social media. They formed a Facebook group to coordinate strategy and compiled a fact sheet making the case that this was a bad investment in Pine Island's future. In August 2018, the city council unanimously rescinded its welcoming resolution.

Leibold, twenty-three, who in addition to her activism on this issue is director of the local chamber of commerce, went on to get elected to the city council last November.

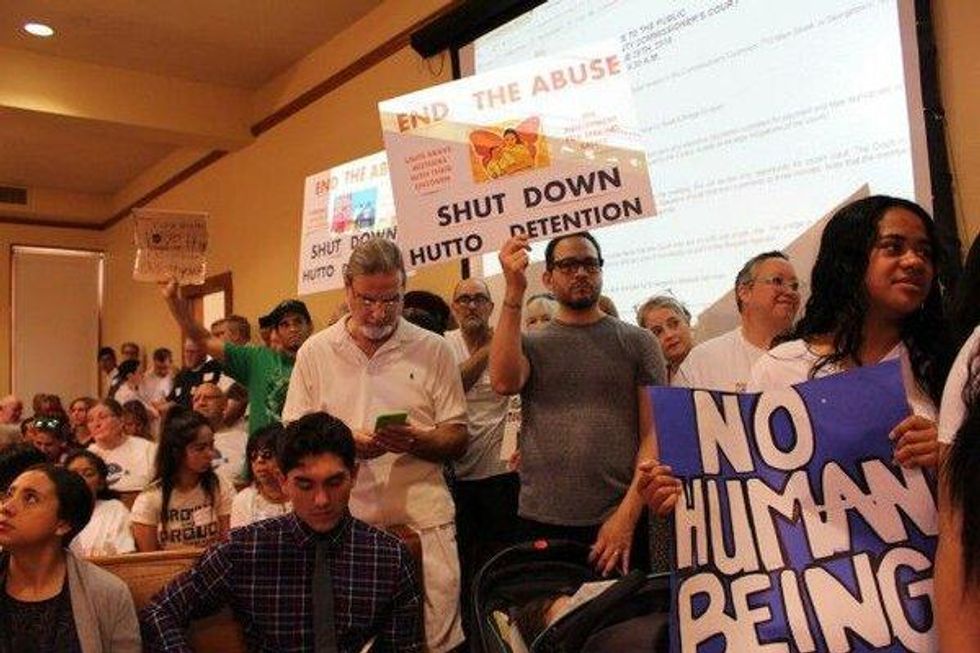

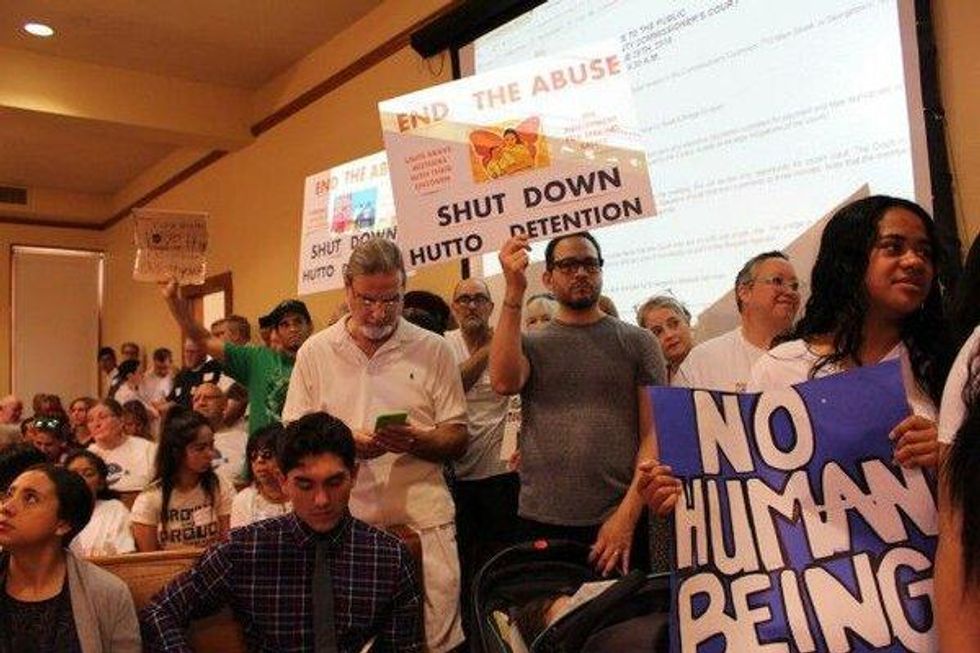

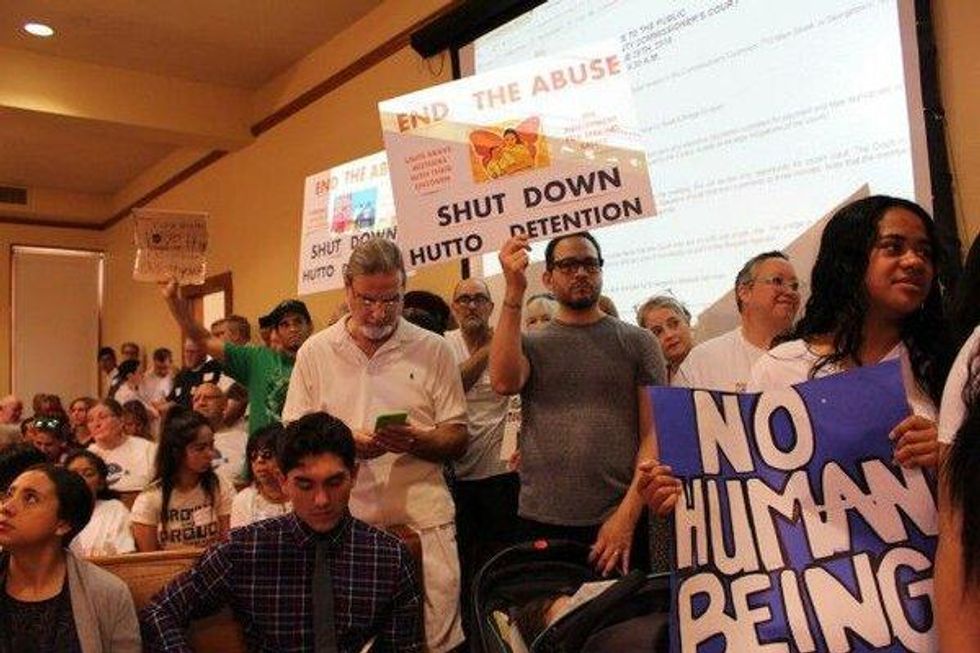

In Taylor, Texas, former ICE detainee Jeymi Moncada is working with Grassroots Leadership, a national nonprofit group, demanding the shutdown of the T. Don Hutto Residential Center, where she was held for thirteen months.

"You can describe the conditions as a house of terror," Moncada says.

A survivor of domestic violence, with scars to prove it, forty-two-year-old Moncada fled Honduras in 2004. She was able to start a new life in Texas but ended up in the Hutto facility in 2010 after being detained by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. That happened after she risked returning to Honduras to bring her children here, according to court papers. They would have joined Moncada's daughter, Jeimi, who was born in Texas. But immigration officers in Mexico stopped Moncada and made her return to Honduras with her other children, who had been cared for by her sister.

Unsafe in Honduras, Moncada returned to the United States only to be apprehended by Border Patrol agents and sent to the Hutto facility. She was confined for more than a year until an immigration judge gave a favorable ruling in her asylum case, withholding deportation because she faced a "clear probability" of persecution if forced to return to Honduras.

But Moncada's detention left her with bitter memories--including seeing Jeimi, then four years old, traumatized by visits to Hutto. "She would scream and cry and say she wanted to be with me," Moncado recalls. "Eventually, they would stop bringing her to visit me because it was too difficult for her."

CoreCivic, the nation's second-largest private prison operator worth $2.4 billion, runs Hutto for ICE. But while the government in Williamson County, where this facility is located, last year voted to terminate its agreement with Hutto, ICE struck a deal directly with CoreCivic to keep the center open.

The Hutto facility is just one of more than 200 detention centers throughout the United States. Most of the larger ones are run by for-profit companies. The ICE detention population has risen from a daily average of 6,785 in 1994 to about 54,000 in June.

And these numbers will continue to grow, as Trump treats immigrants as political fodder. By kicking off his reelection campaign with a promise of mass arrests and deportations, followed by a threat of raids on homes and workplaces of undocumented immigrants in targeted cities, Trump has made clear his disregard for human rights.

The ICE detention figures don't count the unaccompanied children being detained in more than 100 Department of Health and Human Services shelters, most under state supervision. HHS has expanded this capacity from 6,500 beds in October 2017 to 14,300 this past April and has since obtained funding that would allow for an increase up to 23,600 beds. Youths are kept in these shelters until they are placed with sponsors, usually immediate or extended family, while they await their asylum hearings.

Disregard for providing "safe and sanitary" facilities reached a low point in June when the Trump Administration argued before a federal court panel that detained children do not have to be given such basic items as soap and toothpaste, and that sleeping on a concrete floor is not a violation of these standards.

The administration's answer to overcrowded detention facilities is to build even more detention centers, relying on for-profit prison companies--a boom industry under Trump--for construction and management.

Not a thought has been given to why people fleeing persecution and seeking a better life should be put under lock and key. "Taking away someone's freedom is a very extreme act," says Alina Das, co-director of the Immigrant Rights Clinic at New York University School of Law. Immigration detention, she adds, has become a form of "preventative incarceration--a very frightening concept."

When Jonathan fled El Salvador seeking asylum in the United States, he didn't think about having to spend an indefinite period of time in immigration detention. Safe haven was needed, he says, because he was repeatedly threatened by the gang MS-13.

But as soon as he was apprehended by a Border Patrol agent near El Paso, Texas, shortly before Trump's Inauguration, Jonathan got a glimpse of what was in store. He says the agent warned, "We are getting a new President who is going to deport you."

For sixteen months, Jonathan (who asked that his last name not be used) was locked up in a series of detention facilities. Baffled by being treated like a threat rather than as someone fleeing persecution, he tells of his frustration and trauma.

"The uncertainty of not knowing: Am I going to be moved again? Am I going to be deported? Are they going to release me? What's going to happen to me?" says Jonathan, who was finally freed on a $10,000 bond in May 2018 and now lives with relatives in the New York City area as he awaits resolution of his asylum case.

Jonathan's detention started with two dreadful days in one of the Border Patrol's crowded holding units, known collectively by immigrants as La Hielera, "the Icebox," because of the cold and brutal conditions. He had to sleep sitting upright on a metal seat without even a blanket.

He was transferred to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement El Paso Processing Center, then spent a stint at the Cibola County Correctional Center in Milan, New Mexico, before being transferred back to the El Paso Processing Center. Here, Jonathan says, he worked an eight-hour kitchen shift, beginning at 4:30 in the morning, for $1 a day. He saw other detainees put into solitary confinement--"the Hole"--for making their bed the wrong way or not eating fast enough.

Immigration detention is "something you never went to relive--ever."

Immigration detention, says Jonathan, is "something you never went to relive--ever."

At the national level, immigrant rights activists launched the Corporate Backers of Hate campaign in 2017. Holding protests and gathering petitions, the campaign has demanded that the likes of JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo stop bankrolling for-profit prison companies such as the GEO Group and CoreCivic.

"Let's shame the corporate leaders standing by Trump by exposing the way they benefit from Trump," says Ana Maria Archila, who, as co-executive director of the Center for Popular Democracy, is one of the campaign's organizers.

Less than a month after activists held a Valentine's Day "Chase Break Up with Prisons" protest outside the home of JPMorgan Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon in New York City, the investment bank and financial services company announced, "We will no longer bank the private prison industry."

Meanwhile, Wells Fargo said two years ago it had decided to "exit" its banking relationship with private prison companies. When then-CEO Timothy Sloan was pressed on this issue by U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Democrat of New York, at a March hearing, he acknowledged that the company was ending its relationships with CoreCivic and the GEO Group but that the termination process had not been completed. A Wells Fargo spokesperson told The Progressive that this is still expected to happen.

In June, Bank of America said it would stop lending to companies that run private prisons and detention centers. This announcement came after Bank of America officials visited the Homestead facility for unaccompanied immigrant children in Florida.

And SunTrust Banks recently said it won't provide financing to companies that manage private prisons and immigrant-holding facilities.

Pressure to divest is also coming from the American Federation of Teachers, which has within the last year issued a two-part report detailing public pension links to immigrant detention and urging divestment. The union created a "watch list" of asset managers who hold significant shares in the prison industry. As one activist, quoted in the first part of the report, expressed, "This industry has turned human suffering into a billion-dollar business."

Detention and deportation have often been used for racist and political reasons, but not until the 1980s did a network of detention centers emerge.

This is due in part to changes in federal law, beginning with a 1988 statute requiring mandatory detention for those in immigration proceedings convicted of aggravated felonies. The list of offenses covered by mandatory immigration detention was greatly expanded by a 1996 federal law.

The for-profit prison companies were more than willing to step in and provide additional detention space.

"We really outsourced our immigration to private firms," says Lauren-Brooke Eisen, author of the 2017 book Inside Private Prisons: An American Dilemma in the Age of Mass Incarceration. She estimates about 65 percent of immigrant detainees are currently in for-profit prisons; other estimates run as high as nearly 75 percent.

Over the past year, at least seven children have died in U.S. immigration custody or after being detained by immigration agencies at the border. But that only begins to tell how deplorable conditions have become in a system that, according to Detention Watch Network, has seen 189 people die in detention from 2003 to this past April.

In May, unannounced visits by the Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General to five Border Patrol detention sites in the El Paso, Texas, area found that "overcrowding and prolonged detention represent an immediate risk" to detainees' health and safety.

Of particular concern was the El Paso Del Norte Processing Center, where a cell with a maximum capacity of twelve had seventy-six detainees. Detainees were observed standing on toilets in cells, to gain breathing space, because of crowded conditions.

The death of Mariee, a toddler from Guatemala, shows how detrimental detention can be. This nineteen-month-old was in good health when she and her mother, Yazmin Juarez, who is seeking asylum, were sent to the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley on March 5, 2018. By the time Mariee was released twenty days later, she was in failing health, according to a lawsuit filed on behalf of her mother this past March in U.S. District Court in Tucson, Arizona.

"This was not merely an error in medical judgment. It was active neglect of a very sick child," says the lawsuit, which spells out the details of the case.

The defendant in the case is the Arizona city of Eloy, which, despite being 900 miles from Dilley, was allowed to take responsibility for the Dilley facility by modifying its contract with CoreCivic, then called Corrections Corporation of America. Under this arrangement, the lawsuit says, Eloy was to be paid $438,000 a year for overseeing Dilley.

Upon their arrival at Dilley, Mariee and her mother were put in a crowded room with other sick children, and Mariee became ill with upper respiratory symptoms. The lawsuit alleges that Mariee was inadequately and improperly treated, and that her condition continued to deteriorate. She was acutely ill on March 23, when the nurse who examined her said that Mariee would be referred to a medical provider. That never happened because the mother and her ailing daughter were released March 25 and put on a plane to New Jersey.

ICE's record says Mariee was "medically cleared" by a licensed vocational nurse but no medical personnel examined her, according to the lawsuit. The following day, Mariee was admitted to an emergency room in New Jersey with acute respiratory distress. Over the next six weeks, Mariee was transferred to two different hospitals and received specialized care for respiratory failure, but she died May 10 while on advanced life support.

Although the city has denied any culpability for Mariee's death, it has subsequently severed its ties to the Dilley facility. Mariee's mother has also filed an administrative claim for wrongful death against the United States, seeking $60 million.

The deplorable conditions of detention are also evident in hunger strikes at U.S. facilities--at least six in the first few months of this year alone.

In a class-action federal lawsuit filed last year on behalf of three detainees at the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia, the Southern Poverty Law Center is challenging the way CoreCivic has run its "voluntary" work program.

"CoreCivic's economic windfall, and profitability of its immigration detention enterprise, arise from its corporate scheme, plan, and pattern of systemically withholding basic necessities from detained immigrants," says the lawsuit.

One of the plaintiffs, Wilhen Hill Barrientos of Guatemala, alleges that he was required to work seven days a week and was put in the medical segregation unit for two months after he filed a complaint that he was forced to work even though he was sick.

Detainees can be paid as little as $1 a day, according to ICE's detention standards. The lawsuit alleges detainees are sometimes forced to pay for scarce basic necessities, such as toilet paper.

By the center's count, eight other lawsuits have also been filed challenging work conditions at detention centers.

While the sheer number of immigration apprehensions prevents ICE from locking up everyone, U.S. Attorney General William Barr is clearly trying to lock up as many as possible. He has directed the denial of bond for undocumented immigrants who did not enter the United States through a port of entry, even if they have shown a "credible fear" of persecution. On July 2, a federal district judge blocked implementation of Barr's order. And the use of parole to let detainees out of facilities has dropped dramatically.

Liz Martinez, director of advocacy and strategic communications at Freedom for Immigrants, a California-based nonprofit, describes immigration detention as a system of "disappearing people," forcing them to linger in limbo until their day of deportation comes.

Take the case of Rachel, an asylum seeker currently awaiting a decision by the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is reviewing her case. She fled her homeland, the Central African country of Cameroon, in 2016 because she feared being killed for refusing a forced marriage. She says a relative in Cameroon was recently killed because of his support of her.

Rachel, who doesn't want her last name used, turned herself in at the Mexico-U.S. border in January 2017, asking for asylum. She has since been in immigration detention, even though she could have been released to a sister and relatives in Ohio. She has spent most of this time in the El Paso Processing Center. Her plea for asylum was rejected by an immigration judge and dismissed by the Board of Immigration Appeals. A reversal by the Fifth Circuit could be her last hope.

"I live in fear--in depression and confusion," says Rachel in a telephone interview from the detention center. "I don't know what is going to happen, today or tomorrow. They come and get people up at night and deport them." She says that once in February and on two occasions since she filed her notice of appeal to the Fifth Circuit in March, a detention center officer has unsuccessfully tried to get her to sign papers authorizing her deportation.

"I told him I can't go back because my life is in danger," Rachel says. "He told me he doesn't care. He is doing his job. I should sign."

Proposals for immigration detention have sparked grassroots opposition strong enough to prompt for-profit prison companies to withdraw detention proposals and persistent enough to get local governments to rethink their welcome. This resistance began before Donald Trump took office but has intensified under him.

Here are some examples of successful resistance efforts:

Community opposition recently helped defeat Immigration Centers of America's proposed 500-bed detention facility in New Richmond, Wisconsin, about forty miles from St. Paul. "We don't want to participate in abusing people who are here because they were abused in their home country," says Dan Hansen, who was part of the resistance.

Hundreds of postings against the center appeared on Facebook pages, Hansen says. The city's Facebook page was also targeted. Fliers, shared online and handed out in person, provided information for contacting public officials.

"These were people who got together and pushed back and pushed back hard," says Emilio De Torre, who, as director of community engagement for the ACLU of Wisconsin, helped mobilize the resistance.

In April, city officials issued a lengthy report concluding that the proposed facility did not fit New Richmond's city plan, and Immigration Centers withdrew its proposal.

In June, legislation was enacted prohibiting state and local government from entering into agreements with for-profit companies for immigrant detention centers. The measure was prompted by the Village Board of Dwight voting in March to annex eighty-eight acres, clearing the way for an Immigration Centers of America detention facility.

The proposal came after activists successfully organized against possible detention centers over the past eight years at three other Illinois sites--Crete, Joliet, and Hopkins Park--as well as four sites in northwest Indiana: Hobart, Gary, Elkhart County, and the Roselawn community of Newton County.

Whether such efforts succeed in keeping immigration detention centers out remains to be seen. Typically, a detention center involves the local government working with ICE and a for-profit prison company. But over the past fourteen months, local governments in places such as Adelanto, California, and Williamson County, Texas, have cut their ties to detention centers. However, this paves the way for ICE to then work directly with the for-profit prison companies to keep the detention centers open.

Illinois might not be able to stop such an arrangement, but its new law does prevent localities from getting reimbursed for providing infrastructure and other services for a detention facility.

Last fall, a proposal by Immigration Centers of America to convert a former state prison in Ionia into an ICE detention facility was picking up speed under then-Republican Governor Rick Snyder, whose former chief-of-staff, Dennis Muchmore, was reportedly lobbying for the company.

"I don't think you should be making money off of people suffering," says Oscar Castaneda, who, as an organizer for Action of Greater Lansing, helped mobilize the opposition.

With Democrat Gretchen Whitmer's election as Michigan governor in November, the dynamic changed. She reportedly demanded that Immigration Centers of America agree, as a precondition, not to take separated family members--a commitment the company could not make.

Governor Whitmer, who had control over the project because it would be built on state land, blocked the deal in February, with her spokesperson saying that "building more detention facilities won't solve our immigration crisis."

But the governor does not have sway over the GEO Group, which recently struck a deal with ICE to "reactivate" the 1,800-bed North Lake Correctional Facility in Baldwin, Michigan, for housing noncitizens sentenced for immigration offenses and other federal crimes.

In 2017, the Evanston City Council and Uinta County Commissioners passed resolutions in support of Management & Training Corporation locating a detention center in this part of Wyoming. That led to the creation of #WyoSayNo, a coalition of eight state-based activist groups that has held public meetings and contacted public officials to oppose a detention center.

"We just remind Wyoming people of our values," says Antonio Serrano, an organizer with the ACLU of Wyoming. "We don't like people--especially big companies like this--coming in and telling us what we should or should not be doing."

Serrano also reminds residents that the state should not repeat its blatant disregard for human rights during World War II, when it housed a Japanese American internment camp. And, Serrano says, "We don't want to be part of this big deportation machine that this administration is pushing. Being out here in Wyoming, we are better than that."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

In June 2018, Kelly Leibold was among the many residents of Pine Island, Minnesota, caught by surprise when its city council passed a resolution supporting a for-profit prison company, Management & Training Corporation, that wanted to locate a detention facility for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

She responded by helping local residents organize a "No ICE in PI" campaign.

"I don't believe that a detention facility is morally correct," Leibold explains. "People all have immigrant lines in their family. I don't think a detention facility in Pine Island will say good things about our community."

She and about three dozen other activists organized via social media. They formed a Facebook group to coordinate strategy and compiled a fact sheet making the case that this was a bad investment in Pine Island's future. In August 2018, the city council unanimously rescinded its welcoming resolution.

Leibold, twenty-three, who in addition to her activism on this issue is director of the local chamber of commerce, went on to get elected to the city council last November.

In Taylor, Texas, former ICE detainee Jeymi Moncada is working with Grassroots Leadership, a national nonprofit group, demanding the shutdown of the T. Don Hutto Residential Center, where she was held for thirteen months.

"You can describe the conditions as a house of terror," Moncada says.

A survivor of domestic violence, with scars to prove it, forty-two-year-old Moncada fled Honduras in 2004. She was able to start a new life in Texas but ended up in the Hutto facility in 2010 after being detained by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. That happened after she risked returning to Honduras to bring her children here, according to court papers. They would have joined Moncada's daughter, Jeimi, who was born in Texas. But immigration officers in Mexico stopped Moncada and made her return to Honduras with her other children, who had been cared for by her sister.

Unsafe in Honduras, Moncada returned to the United States only to be apprehended by Border Patrol agents and sent to the Hutto facility. She was confined for more than a year until an immigration judge gave a favorable ruling in her asylum case, withholding deportation because she faced a "clear probability" of persecution if forced to return to Honduras.

But Moncada's detention left her with bitter memories--including seeing Jeimi, then four years old, traumatized by visits to Hutto. "She would scream and cry and say she wanted to be with me," Moncado recalls. "Eventually, they would stop bringing her to visit me because it was too difficult for her."

CoreCivic, the nation's second-largest private prison operator worth $2.4 billion, runs Hutto for ICE. But while the government in Williamson County, where this facility is located, last year voted to terminate its agreement with Hutto, ICE struck a deal directly with CoreCivic to keep the center open.

The Hutto facility is just one of more than 200 detention centers throughout the United States. Most of the larger ones are run by for-profit companies. The ICE detention population has risen from a daily average of 6,785 in 1994 to about 54,000 in June.

And these numbers will continue to grow, as Trump treats immigrants as political fodder. By kicking off his reelection campaign with a promise of mass arrests and deportations, followed by a threat of raids on homes and workplaces of undocumented immigrants in targeted cities, Trump has made clear his disregard for human rights.

The ICE detention figures don't count the unaccompanied children being detained in more than 100 Department of Health and Human Services shelters, most under state supervision. HHS has expanded this capacity from 6,500 beds in October 2017 to 14,300 this past April and has since obtained funding that would allow for an increase up to 23,600 beds. Youths are kept in these shelters until they are placed with sponsors, usually immediate or extended family, while they await their asylum hearings.

Disregard for providing "safe and sanitary" facilities reached a low point in June when the Trump Administration argued before a federal court panel that detained children do not have to be given such basic items as soap and toothpaste, and that sleeping on a concrete floor is not a violation of these standards.

The administration's answer to overcrowded detention facilities is to build even more detention centers, relying on for-profit prison companies--a boom industry under Trump--for construction and management.

Not a thought has been given to why people fleeing persecution and seeking a better life should be put under lock and key. "Taking away someone's freedom is a very extreme act," says Alina Das, co-director of the Immigrant Rights Clinic at New York University School of Law. Immigration detention, she adds, has become a form of "preventative incarceration--a very frightening concept."

When Jonathan fled El Salvador seeking asylum in the United States, he didn't think about having to spend an indefinite period of time in immigration detention. Safe haven was needed, he says, because he was repeatedly threatened by the gang MS-13.

But as soon as he was apprehended by a Border Patrol agent near El Paso, Texas, shortly before Trump's Inauguration, Jonathan got a glimpse of what was in store. He says the agent warned, "We are getting a new President who is going to deport you."

For sixteen months, Jonathan (who asked that his last name not be used) was locked up in a series of detention facilities. Baffled by being treated like a threat rather than as someone fleeing persecution, he tells of his frustration and trauma.

"The uncertainty of not knowing: Am I going to be moved again? Am I going to be deported? Are they going to release me? What's going to happen to me?" says Jonathan, who was finally freed on a $10,000 bond in May 2018 and now lives with relatives in the New York City area as he awaits resolution of his asylum case.

Jonathan's detention started with two dreadful days in one of the Border Patrol's crowded holding units, known collectively by immigrants as La Hielera, "the Icebox," because of the cold and brutal conditions. He had to sleep sitting upright on a metal seat without even a blanket.

He was transferred to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement El Paso Processing Center, then spent a stint at the Cibola County Correctional Center in Milan, New Mexico, before being transferred back to the El Paso Processing Center. Here, Jonathan says, he worked an eight-hour kitchen shift, beginning at 4:30 in the morning, for $1 a day. He saw other detainees put into solitary confinement--"the Hole"--for making their bed the wrong way or not eating fast enough.

Immigration detention is "something you never went to relive--ever."

Immigration detention, says Jonathan, is "something you never went to relive--ever."

At the national level, immigrant rights activists launched the Corporate Backers of Hate campaign in 2017. Holding protests and gathering petitions, the campaign has demanded that the likes of JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo stop bankrolling for-profit prison companies such as the GEO Group and CoreCivic.

"Let's shame the corporate leaders standing by Trump by exposing the way they benefit from Trump," says Ana Maria Archila, who, as co-executive director of the Center for Popular Democracy, is one of the campaign's organizers.

Less than a month after activists held a Valentine's Day "Chase Break Up with Prisons" protest outside the home of JPMorgan Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon in New York City, the investment bank and financial services company announced, "We will no longer bank the private prison industry."

Meanwhile, Wells Fargo said two years ago it had decided to "exit" its banking relationship with private prison companies. When then-CEO Timothy Sloan was pressed on this issue by U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Democrat of New York, at a March hearing, he acknowledged that the company was ending its relationships with CoreCivic and the GEO Group but that the termination process had not been completed. A Wells Fargo spokesperson told The Progressive that this is still expected to happen.

In June, Bank of America said it would stop lending to companies that run private prisons and detention centers. This announcement came after Bank of America officials visited the Homestead facility for unaccompanied immigrant children in Florida.

And SunTrust Banks recently said it won't provide financing to companies that manage private prisons and immigrant-holding facilities.

Pressure to divest is also coming from the American Federation of Teachers, which has within the last year issued a two-part report detailing public pension links to immigrant detention and urging divestment. The union created a "watch list" of asset managers who hold significant shares in the prison industry. As one activist, quoted in the first part of the report, expressed, "This industry has turned human suffering into a billion-dollar business."

Detention and deportation have often been used for racist and political reasons, but not until the 1980s did a network of detention centers emerge.

This is due in part to changes in federal law, beginning with a 1988 statute requiring mandatory detention for those in immigration proceedings convicted of aggravated felonies. The list of offenses covered by mandatory immigration detention was greatly expanded by a 1996 federal law.

The for-profit prison companies were more than willing to step in and provide additional detention space.

"We really outsourced our immigration to private firms," says Lauren-Brooke Eisen, author of the 2017 book Inside Private Prisons: An American Dilemma in the Age of Mass Incarceration. She estimates about 65 percent of immigrant detainees are currently in for-profit prisons; other estimates run as high as nearly 75 percent.

Over the past year, at least seven children have died in U.S. immigration custody or after being detained by immigration agencies at the border. But that only begins to tell how deplorable conditions have become in a system that, according to Detention Watch Network, has seen 189 people die in detention from 2003 to this past April.

In May, unannounced visits by the Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General to five Border Patrol detention sites in the El Paso, Texas, area found that "overcrowding and prolonged detention represent an immediate risk" to detainees' health and safety.

Of particular concern was the El Paso Del Norte Processing Center, where a cell with a maximum capacity of twelve had seventy-six detainees. Detainees were observed standing on toilets in cells, to gain breathing space, because of crowded conditions.

The death of Mariee, a toddler from Guatemala, shows how detrimental detention can be. This nineteen-month-old was in good health when she and her mother, Yazmin Juarez, who is seeking asylum, were sent to the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley on March 5, 2018. By the time Mariee was released twenty days later, she was in failing health, according to a lawsuit filed on behalf of her mother this past March in U.S. District Court in Tucson, Arizona.

"This was not merely an error in medical judgment. It was active neglect of a very sick child," says the lawsuit, which spells out the details of the case.

The defendant in the case is the Arizona city of Eloy, which, despite being 900 miles from Dilley, was allowed to take responsibility for the Dilley facility by modifying its contract with CoreCivic, then called Corrections Corporation of America. Under this arrangement, the lawsuit says, Eloy was to be paid $438,000 a year for overseeing Dilley.

Upon their arrival at Dilley, Mariee and her mother were put in a crowded room with other sick children, and Mariee became ill with upper respiratory symptoms. The lawsuit alleges that Mariee was inadequately and improperly treated, and that her condition continued to deteriorate. She was acutely ill on March 23, when the nurse who examined her said that Mariee would be referred to a medical provider. That never happened because the mother and her ailing daughter were released March 25 and put on a plane to New Jersey.

ICE's record says Mariee was "medically cleared" by a licensed vocational nurse but no medical personnel examined her, according to the lawsuit. The following day, Mariee was admitted to an emergency room in New Jersey with acute respiratory distress. Over the next six weeks, Mariee was transferred to two different hospitals and received specialized care for respiratory failure, but she died May 10 while on advanced life support.

Although the city has denied any culpability for Mariee's death, it has subsequently severed its ties to the Dilley facility. Mariee's mother has also filed an administrative claim for wrongful death against the United States, seeking $60 million.

The deplorable conditions of detention are also evident in hunger strikes at U.S. facilities--at least six in the first few months of this year alone.

In a class-action federal lawsuit filed last year on behalf of three detainees at the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia, the Southern Poverty Law Center is challenging the way CoreCivic has run its "voluntary" work program.

"CoreCivic's economic windfall, and profitability of its immigration detention enterprise, arise from its corporate scheme, plan, and pattern of systemically withholding basic necessities from detained immigrants," says the lawsuit.

One of the plaintiffs, Wilhen Hill Barrientos of Guatemala, alleges that he was required to work seven days a week and was put in the medical segregation unit for two months after he filed a complaint that he was forced to work even though he was sick.

Detainees can be paid as little as $1 a day, according to ICE's detention standards. The lawsuit alleges detainees are sometimes forced to pay for scarce basic necessities, such as toilet paper.

By the center's count, eight other lawsuits have also been filed challenging work conditions at detention centers.

While the sheer number of immigration apprehensions prevents ICE from locking up everyone, U.S. Attorney General William Barr is clearly trying to lock up as many as possible. He has directed the denial of bond for undocumented immigrants who did not enter the United States through a port of entry, even if they have shown a "credible fear" of persecution. On July 2, a federal district judge blocked implementation of Barr's order. And the use of parole to let detainees out of facilities has dropped dramatically.

Liz Martinez, director of advocacy and strategic communications at Freedom for Immigrants, a California-based nonprofit, describes immigration detention as a system of "disappearing people," forcing them to linger in limbo until their day of deportation comes.

Take the case of Rachel, an asylum seeker currently awaiting a decision by the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is reviewing her case. She fled her homeland, the Central African country of Cameroon, in 2016 because she feared being killed for refusing a forced marriage. She says a relative in Cameroon was recently killed because of his support of her.

Rachel, who doesn't want her last name used, turned herself in at the Mexico-U.S. border in January 2017, asking for asylum. She has since been in immigration detention, even though she could have been released to a sister and relatives in Ohio. She has spent most of this time in the El Paso Processing Center. Her plea for asylum was rejected by an immigration judge and dismissed by the Board of Immigration Appeals. A reversal by the Fifth Circuit could be her last hope.

"I live in fear--in depression and confusion," says Rachel in a telephone interview from the detention center. "I don't know what is going to happen, today or tomorrow. They come and get people up at night and deport them." She says that once in February and on two occasions since she filed her notice of appeal to the Fifth Circuit in March, a detention center officer has unsuccessfully tried to get her to sign papers authorizing her deportation.

"I told him I can't go back because my life is in danger," Rachel says. "He told me he doesn't care. He is doing his job. I should sign."

Proposals for immigration detention have sparked grassroots opposition strong enough to prompt for-profit prison companies to withdraw detention proposals and persistent enough to get local governments to rethink their welcome. This resistance began before Donald Trump took office but has intensified under him.

Here are some examples of successful resistance efforts:

Community opposition recently helped defeat Immigration Centers of America's proposed 500-bed detention facility in New Richmond, Wisconsin, about forty miles from St. Paul. "We don't want to participate in abusing people who are here because they were abused in their home country," says Dan Hansen, who was part of the resistance.

Hundreds of postings against the center appeared on Facebook pages, Hansen says. The city's Facebook page was also targeted. Fliers, shared online and handed out in person, provided information for contacting public officials.

"These were people who got together and pushed back and pushed back hard," says Emilio De Torre, who, as director of community engagement for the ACLU of Wisconsin, helped mobilize the resistance.

In April, city officials issued a lengthy report concluding that the proposed facility did not fit New Richmond's city plan, and Immigration Centers withdrew its proposal.

In June, legislation was enacted prohibiting state and local government from entering into agreements with for-profit companies for immigrant detention centers. The measure was prompted by the Village Board of Dwight voting in March to annex eighty-eight acres, clearing the way for an Immigration Centers of America detention facility.

The proposal came after activists successfully organized against possible detention centers over the past eight years at three other Illinois sites--Crete, Joliet, and Hopkins Park--as well as four sites in northwest Indiana: Hobart, Gary, Elkhart County, and the Roselawn community of Newton County.

Whether such efforts succeed in keeping immigration detention centers out remains to be seen. Typically, a detention center involves the local government working with ICE and a for-profit prison company. But over the past fourteen months, local governments in places such as Adelanto, California, and Williamson County, Texas, have cut their ties to detention centers. However, this paves the way for ICE to then work directly with the for-profit prison companies to keep the detention centers open.

Illinois might not be able to stop such an arrangement, but its new law does prevent localities from getting reimbursed for providing infrastructure and other services for a detention facility.

Last fall, a proposal by Immigration Centers of America to convert a former state prison in Ionia into an ICE detention facility was picking up speed under then-Republican Governor Rick Snyder, whose former chief-of-staff, Dennis Muchmore, was reportedly lobbying for the company.

"I don't think you should be making money off of people suffering," says Oscar Castaneda, who, as an organizer for Action of Greater Lansing, helped mobilize the opposition.

With Democrat Gretchen Whitmer's election as Michigan governor in November, the dynamic changed. She reportedly demanded that Immigration Centers of America agree, as a precondition, not to take separated family members--a commitment the company could not make.

Governor Whitmer, who had control over the project because it would be built on state land, blocked the deal in February, with her spokesperson saying that "building more detention facilities won't solve our immigration crisis."

But the governor does not have sway over the GEO Group, which recently struck a deal with ICE to "reactivate" the 1,800-bed North Lake Correctional Facility in Baldwin, Michigan, for housing noncitizens sentenced for immigration offenses and other federal crimes.

In 2017, the Evanston City Council and Uinta County Commissioners passed resolutions in support of Management & Training Corporation locating a detention center in this part of Wyoming. That led to the creation of #WyoSayNo, a coalition of eight state-based activist groups that has held public meetings and contacted public officials to oppose a detention center.

"We just remind Wyoming people of our values," says Antonio Serrano, an organizer with the ACLU of Wyoming. "We don't like people--especially big companies like this--coming in and telling us what we should or should not be doing."

Serrano also reminds residents that the state should not repeat its blatant disregard for human rights during World War II, when it housed a Japanese American internment camp. And, Serrano says, "We don't want to be part of this big deportation machine that this administration is pushing. Being out here in Wyoming, we are better than that."

In June 2018, Kelly Leibold was among the many residents of Pine Island, Minnesota, caught by surprise when its city council passed a resolution supporting a for-profit prison company, Management & Training Corporation, that wanted to locate a detention facility for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

She responded by helping local residents organize a "No ICE in PI" campaign.

"I don't believe that a detention facility is morally correct," Leibold explains. "People all have immigrant lines in their family. I don't think a detention facility in Pine Island will say good things about our community."

She and about three dozen other activists organized via social media. They formed a Facebook group to coordinate strategy and compiled a fact sheet making the case that this was a bad investment in Pine Island's future. In August 2018, the city council unanimously rescinded its welcoming resolution.

Leibold, twenty-three, who in addition to her activism on this issue is director of the local chamber of commerce, went on to get elected to the city council last November.

In Taylor, Texas, former ICE detainee Jeymi Moncada is working with Grassroots Leadership, a national nonprofit group, demanding the shutdown of the T. Don Hutto Residential Center, where she was held for thirteen months.

"You can describe the conditions as a house of terror," Moncada says.

A survivor of domestic violence, with scars to prove it, forty-two-year-old Moncada fled Honduras in 2004. She was able to start a new life in Texas but ended up in the Hutto facility in 2010 after being detained by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. That happened after she risked returning to Honduras to bring her children here, according to court papers. They would have joined Moncada's daughter, Jeimi, who was born in Texas. But immigration officers in Mexico stopped Moncada and made her return to Honduras with her other children, who had been cared for by her sister.

Unsafe in Honduras, Moncada returned to the United States only to be apprehended by Border Patrol agents and sent to the Hutto facility. She was confined for more than a year until an immigration judge gave a favorable ruling in her asylum case, withholding deportation because she faced a "clear probability" of persecution if forced to return to Honduras.

But Moncada's detention left her with bitter memories--including seeing Jeimi, then four years old, traumatized by visits to Hutto. "She would scream and cry and say she wanted to be with me," Moncado recalls. "Eventually, they would stop bringing her to visit me because it was too difficult for her."

CoreCivic, the nation's second-largest private prison operator worth $2.4 billion, runs Hutto for ICE. But while the government in Williamson County, where this facility is located, last year voted to terminate its agreement with Hutto, ICE struck a deal directly with CoreCivic to keep the center open.

The Hutto facility is just one of more than 200 detention centers throughout the United States. Most of the larger ones are run by for-profit companies. The ICE detention population has risen from a daily average of 6,785 in 1994 to about 54,000 in June.

And these numbers will continue to grow, as Trump treats immigrants as political fodder. By kicking off his reelection campaign with a promise of mass arrests and deportations, followed by a threat of raids on homes and workplaces of undocumented immigrants in targeted cities, Trump has made clear his disregard for human rights.

The ICE detention figures don't count the unaccompanied children being detained in more than 100 Department of Health and Human Services shelters, most under state supervision. HHS has expanded this capacity from 6,500 beds in October 2017 to 14,300 this past April and has since obtained funding that would allow for an increase up to 23,600 beds. Youths are kept in these shelters until they are placed with sponsors, usually immediate or extended family, while they await their asylum hearings.

Disregard for providing "safe and sanitary" facilities reached a low point in June when the Trump Administration argued before a federal court panel that detained children do not have to be given such basic items as soap and toothpaste, and that sleeping on a concrete floor is not a violation of these standards.

The administration's answer to overcrowded detention facilities is to build even more detention centers, relying on for-profit prison companies--a boom industry under Trump--for construction and management.

Not a thought has been given to why people fleeing persecution and seeking a better life should be put under lock and key. "Taking away someone's freedom is a very extreme act," says Alina Das, co-director of the Immigrant Rights Clinic at New York University School of Law. Immigration detention, she adds, has become a form of "preventative incarceration--a very frightening concept."

When Jonathan fled El Salvador seeking asylum in the United States, he didn't think about having to spend an indefinite period of time in immigration detention. Safe haven was needed, he says, because he was repeatedly threatened by the gang MS-13.

But as soon as he was apprehended by a Border Patrol agent near El Paso, Texas, shortly before Trump's Inauguration, Jonathan got a glimpse of what was in store. He says the agent warned, "We are getting a new President who is going to deport you."

For sixteen months, Jonathan (who asked that his last name not be used) was locked up in a series of detention facilities. Baffled by being treated like a threat rather than as someone fleeing persecution, he tells of his frustration and trauma.

"The uncertainty of not knowing: Am I going to be moved again? Am I going to be deported? Are they going to release me? What's going to happen to me?" says Jonathan, who was finally freed on a $10,000 bond in May 2018 and now lives with relatives in the New York City area as he awaits resolution of his asylum case.

Jonathan's detention started with two dreadful days in one of the Border Patrol's crowded holding units, known collectively by immigrants as La Hielera, "the Icebox," because of the cold and brutal conditions. He had to sleep sitting upright on a metal seat without even a blanket.

He was transferred to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement El Paso Processing Center, then spent a stint at the Cibola County Correctional Center in Milan, New Mexico, before being transferred back to the El Paso Processing Center. Here, Jonathan says, he worked an eight-hour kitchen shift, beginning at 4:30 in the morning, for $1 a day. He saw other detainees put into solitary confinement--"the Hole"--for making their bed the wrong way or not eating fast enough.

Immigration detention is "something you never went to relive--ever."

Immigration detention, says Jonathan, is "something you never went to relive--ever."

At the national level, immigrant rights activists launched the Corporate Backers of Hate campaign in 2017. Holding protests and gathering petitions, the campaign has demanded that the likes of JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo stop bankrolling for-profit prison companies such as the GEO Group and CoreCivic.

"Let's shame the corporate leaders standing by Trump by exposing the way they benefit from Trump," says Ana Maria Archila, who, as co-executive director of the Center for Popular Democracy, is one of the campaign's organizers.

Less than a month after activists held a Valentine's Day "Chase Break Up with Prisons" protest outside the home of JPMorgan Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon in New York City, the investment bank and financial services company announced, "We will no longer bank the private prison industry."

Meanwhile, Wells Fargo said two years ago it had decided to "exit" its banking relationship with private prison companies. When then-CEO Timothy Sloan was pressed on this issue by U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Democrat of New York, at a March hearing, he acknowledged that the company was ending its relationships with CoreCivic and the GEO Group but that the termination process had not been completed. A Wells Fargo spokesperson told The Progressive that this is still expected to happen.

In June, Bank of America said it would stop lending to companies that run private prisons and detention centers. This announcement came after Bank of America officials visited the Homestead facility for unaccompanied immigrant children in Florida.

And SunTrust Banks recently said it won't provide financing to companies that manage private prisons and immigrant-holding facilities.

Pressure to divest is also coming from the American Federation of Teachers, which has within the last year issued a two-part report detailing public pension links to immigrant detention and urging divestment. The union created a "watch list" of asset managers who hold significant shares in the prison industry. As one activist, quoted in the first part of the report, expressed, "This industry has turned human suffering into a billion-dollar business."

Detention and deportation have often been used for racist and political reasons, but not until the 1980s did a network of detention centers emerge.

This is due in part to changes in federal law, beginning with a 1988 statute requiring mandatory detention for those in immigration proceedings convicted of aggravated felonies. The list of offenses covered by mandatory immigration detention was greatly expanded by a 1996 federal law.

The for-profit prison companies were more than willing to step in and provide additional detention space.

"We really outsourced our immigration to private firms," says Lauren-Brooke Eisen, author of the 2017 book Inside Private Prisons: An American Dilemma in the Age of Mass Incarceration. She estimates about 65 percent of immigrant detainees are currently in for-profit prisons; other estimates run as high as nearly 75 percent.

Over the past year, at least seven children have died in U.S. immigration custody or after being detained by immigration agencies at the border. But that only begins to tell how deplorable conditions have become in a system that, according to Detention Watch Network, has seen 189 people die in detention from 2003 to this past April.

In May, unannounced visits by the Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General to five Border Patrol detention sites in the El Paso, Texas, area found that "overcrowding and prolonged detention represent an immediate risk" to detainees' health and safety.

Of particular concern was the El Paso Del Norte Processing Center, where a cell with a maximum capacity of twelve had seventy-six detainees. Detainees were observed standing on toilets in cells, to gain breathing space, because of crowded conditions.

The death of Mariee, a toddler from Guatemala, shows how detrimental detention can be. This nineteen-month-old was in good health when she and her mother, Yazmin Juarez, who is seeking asylum, were sent to the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley on March 5, 2018. By the time Mariee was released twenty days later, she was in failing health, according to a lawsuit filed on behalf of her mother this past March in U.S. District Court in Tucson, Arizona.

"This was not merely an error in medical judgment. It was active neglect of a very sick child," says the lawsuit, which spells out the details of the case.

The defendant in the case is the Arizona city of Eloy, which, despite being 900 miles from Dilley, was allowed to take responsibility for the Dilley facility by modifying its contract with CoreCivic, then called Corrections Corporation of America. Under this arrangement, the lawsuit says, Eloy was to be paid $438,000 a year for overseeing Dilley.

Upon their arrival at Dilley, Mariee and her mother were put in a crowded room with other sick children, and Mariee became ill with upper respiratory symptoms. The lawsuit alleges that Mariee was inadequately and improperly treated, and that her condition continued to deteriorate. She was acutely ill on March 23, when the nurse who examined her said that Mariee would be referred to a medical provider. That never happened because the mother and her ailing daughter were released March 25 and put on a plane to New Jersey.

ICE's record says Mariee was "medically cleared" by a licensed vocational nurse but no medical personnel examined her, according to the lawsuit. The following day, Mariee was admitted to an emergency room in New Jersey with acute respiratory distress. Over the next six weeks, Mariee was transferred to two different hospitals and received specialized care for respiratory failure, but she died May 10 while on advanced life support.

Although the city has denied any culpability for Mariee's death, it has subsequently severed its ties to the Dilley facility. Mariee's mother has also filed an administrative claim for wrongful death against the United States, seeking $60 million.

The deplorable conditions of detention are also evident in hunger strikes at U.S. facilities--at least six in the first few months of this year alone.

In a class-action federal lawsuit filed last year on behalf of three detainees at the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia, the Southern Poverty Law Center is challenging the way CoreCivic has run its "voluntary" work program.

"CoreCivic's economic windfall, and profitability of its immigration detention enterprise, arise from its corporate scheme, plan, and pattern of systemically withholding basic necessities from detained immigrants," says the lawsuit.

One of the plaintiffs, Wilhen Hill Barrientos of Guatemala, alleges that he was required to work seven days a week and was put in the medical segregation unit for two months after he filed a complaint that he was forced to work even though he was sick.

Detainees can be paid as little as $1 a day, according to ICE's detention standards. The lawsuit alleges detainees are sometimes forced to pay for scarce basic necessities, such as toilet paper.

By the center's count, eight other lawsuits have also been filed challenging work conditions at detention centers.

While the sheer number of immigration apprehensions prevents ICE from locking up everyone, U.S. Attorney General William Barr is clearly trying to lock up as many as possible. He has directed the denial of bond for undocumented immigrants who did not enter the United States through a port of entry, even if they have shown a "credible fear" of persecution. On July 2, a federal district judge blocked implementation of Barr's order. And the use of parole to let detainees out of facilities has dropped dramatically.

Liz Martinez, director of advocacy and strategic communications at Freedom for Immigrants, a California-based nonprofit, describes immigration detention as a system of "disappearing people," forcing them to linger in limbo until their day of deportation comes.

Take the case of Rachel, an asylum seeker currently awaiting a decision by the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is reviewing her case. She fled her homeland, the Central African country of Cameroon, in 2016 because she feared being killed for refusing a forced marriage. She says a relative in Cameroon was recently killed because of his support of her.

Rachel, who doesn't want her last name used, turned herself in at the Mexico-U.S. border in January 2017, asking for asylum. She has since been in immigration detention, even though she could have been released to a sister and relatives in Ohio. She has spent most of this time in the El Paso Processing Center. Her plea for asylum was rejected by an immigration judge and dismissed by the Board of Immigration Appeals. A reversal by the Fifth Circuit could be her last hope.

"I live in fear--in depression and confusion," says Rachel in a telephone interview from the detention center. "I don't know what is going to happen, today or tomorrow. They come and get people up at night and deport them." She says that once in February and on two occasions since she filed her notice of appeal to the Fifth Circuit in March, a detention center officer has unsuccessfully tried to get her to sign papers authorizing her deportation.

"I told him I can't go back because my life is in danger," Rachel says. "He told me he doesn't care. He is doing his job. I should sign."

Proposals for immigration detention have sparked grassroots opposition strong enough to prompt for-profit prison companies to withdraw detention proposals and persistent enough to get local governments to rethink their welcome. This resistance began before Donald Trump took office but has intensified under him.

Here are some examples of successful resistance efforts:

Community opposition recently helped defeat Immigration Centers of America's proposed 500-bed detention facility in New Richmond, Wisconsin, about forty miles from St. Paul. "We don't want to participate in abusing people who are here because they were abused in their home country," says Dan Hansen, who was part of the resistance.

Hundreds of postings against the center appeared on Facebook pages, Hansen says. The city's Facebook page was also targeted. Fliers, shared online and handed out in person, provided information for contacting public officials.

"These were people who got together and pushed back and pushed back hard," says Emilio De Torre, who, as director of community engagement for the ACLU of Wisconsin, helped mobilize the resistance.

In April, city officials issued a lengthy report concluding that the proposed facility did not fit New Richmond's city plan, and Immigration Centers withdrew its proposal.

In June, legislation was enacted prohibiting state and local government from entering into agreements with for-profit companies for immigrant detention centers. The measure was prompted by the Village Board of Dwight voting in March to annex eighty-eight acres, clearing the way for an Immigration Centers of America detention facility.

The proposal came after activists successfully organized against possible detention centers over the past eight years at three other Illinois sites--Crete, Joliet, and Hopkins Park--as well as four sites in northwest Indiana: Hobart, Gary, Elkhart County, and the Roselawn community of Newton County.

Whether such efforts succeed in keeping immigration detention centers out remains to be seen. Typically, a detention center involves the local government working with ICE and a for-profit prison company. But over the past fourteen months, local governments in places such as Adelanto, California, and Williamson County, Texas, have cut their ties to detention centers. However, this paves the way for ICE to then work directly with the for-profit prison companies to keep the detention centers open.

Illinois might not be able to stop such an arrangement, but its new law does prevent localities from getting reimbursed for providing infrastructure and other services for a detention facility.

Last fall, a proposal by Immigration Centers of America to convert a former state prison in Ionia into an ICE detention facility was picking up speed under then-Republican Governor Rick Snyder, whose former chief-of-staff, Dennis Muchmore, was reportedly lobbying for the company.

"I don't think you should be making money off of people suffering," says Oscar Castaneda, who, as an organizer for Action of Greater Lansing, helped mobilize the opposition.

With Democrat Gretchen Whitmer's election as Michigan governor in November, the dynamic changed. She reportedly demanded that Immigration Centers of America agree, as a precondition, not to take separated family members--a commitment the company could not make.

Governor Whitmer, who had control over the project because it would be built on state land, blocked the deal in February, with her spokesperson saying that "building more detention facilities won't solve our immigration crisis."

But the governor does not have sway over the GEO Group, which recently struck a deal with ICE to "reactivate" the 1,800-bed North Lake Correctional Facility in Baldwin, Michigan, for housing noncitizens sentenced for immigration offenses and other federal crimes.

In 2017, the Evanston City Council and Uinta County Commissioners passed resolutions in support of Management & Training Corporation locating a detention center in this part of Wyoming. That led to the creation of #WyoSayNo, a coalition of eight state-based activist groups that has held public meetings and contacted public officials to oppose a detention center.

"We just remind Wyoming people of our values," says Antonio Serrano, an organizer with the ACLU of Wyoming. "We don't like people--especially big companies like this--coming in and telling us what we should or should not be doing."

Serrano also reminds residents that the state should not repeat its blatant disregard for human rights during World War II, when it housed a Japanese American internment camp. And, Serrano says, "We don't want to be part of this big deportation machine that this administration is pushing. Being out here in Wyoming, we are better than that."