Top campaign staffers for Bernie Sanders held a press call Monday, and the message was positive. The senator, they said, is doing well and won the last debate. And polls show, they added, that the country cares about his favored issues, particularly health care.

But that's not always, his staff noted pointedly to listening reporters, reflected in the coverage.

"It seems like there's a direct correlation," said senior advisor Jeff Weaver, who was on the call alongside campaign co-chair and Ohio state senator Nina Turner and pollster Ben Tulchin. "The better [Sanders] does, the less coverage he receives. The worse he does, the more."

Sanders still can't walk in a straight line without attracting negative press. A New York Times story this week about Bernie's trip to the Iowa state fair dinged him for having "power-walked by the Ferris Wheel" and "gobbled a corn dog" during a journey in which he "spoke to almost no one." This, reporter Sydney Ember concluded, underscored the peril of a campaign based on ideas rather than "establishing human connections."

The Times wrote the same story four years ago, when Bernie's crime was walking down 6th Avenue, "swinging hands with his wife, Jane," and "talking as little as possible to people." Observing that Bernie signed the cast of a 9 year-old girl without schmoozing her undecided-voter father, reporter Patrick Healy concluded he was "surprisingly impersonal." Headline: "Bernie Sanders does not kiss babies. That a problem?"

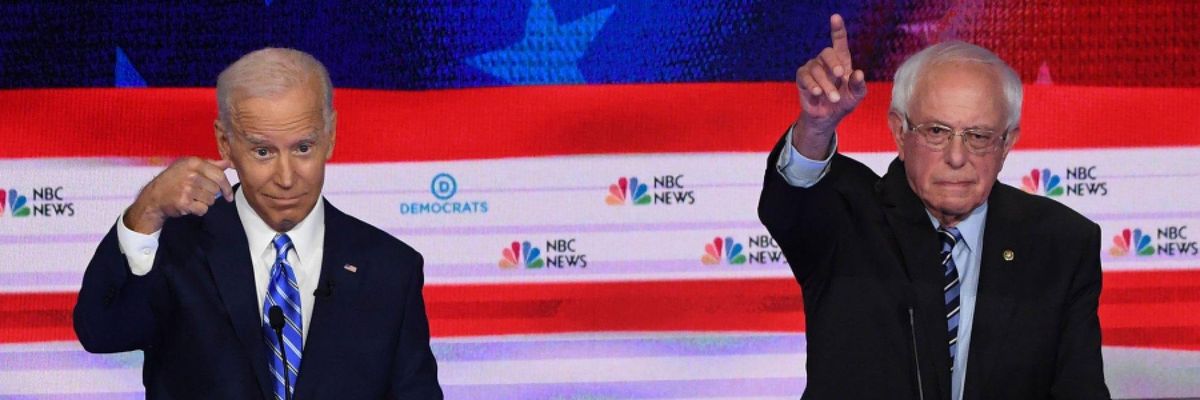

While Sanders can't eat a corn dog without taking a hit, frontrunner Joe Biden is testing the limits of editorial slack. Biden struggles constantly with bizarre or flat-out inappropriate statements, an issue that goes beyond the speech impediment he had as a child. This year he's putting together a George W. Bushian mashupof goofs,with "We choose truth over facts!" and the more troubling "poor kids are just as talented as white kids!" the latest. Tweeting about Biden's lack of a "full deck" seems among Donald Trump's favorite things to do of late, an ominous sign for a potential general election.

Biden's gaffes have earned press, some negative (he's "raising questions" about "electability," says The Hill), but some defiant (the idea that gaffes are important in the Trump age is "particularly offensive," says aWashington Post columnist). The question of whether Biden's verbal fumbles deserve censure, laughter, or a break has become the prevailing controversy around the front-runner.

Meanwhile the larger issue of what Biden's politics are, and whether they're an improvement over the platform that lost to Trump four years ago, recedes. Even Sanders has seemed unsure if he should or shouldn't throw his trademark vituperation at his old Senate colleague.

A Hill/HarrisX poll from last week had Bernie as the second choice of 27% of Biden voters, with Kamala Harris second at 15%, Beto O'Rourke third, Pete Buttigieg fourth, and Elizabeth Warren fifth at 8%. An April Morning Consult survey likewise had Sanders as the second choice of 31% of Biden voters, again followed by Harris (13%), with Warren third at 10%.

The second choice of most Sanders voters, meanwhile,is Biden, not Warren.

Basically, Biden is taking working-class votes away from Sanders, and Sanders has seemed slow to grasp this.

The strength of Bernie Sanders as a politician has always been his believability as a bringer of change. His unsparing attitude on the stump has always been a part of this formula. Whether or not you feel Bernie has the right policy prescription, there's no doubt what sideof things he's on. His distaste for insurance companies, tech plutocrats like Jeff Bezos, fast food chains, Disney, bankers, the "mainstream media," corporate cash-gobbling pols in both parties, and other vermin is too visceral and obvious to miss.

In 2016, Bernie's disagreements with Hillary Clinton were profound. He stressed he was a different kind of person than Clinton, not just someone who clashed on policy.

"The first difference is I don't take money from big banks," he said. Another oft-quoted line: "I am proud to say Henry Kissinger is not my friend," a reference to Hillary Clinton saying she was "flattered" by Kissinger's praise.

2020 is different. Sanders has long referred to Biden has his friend. In 2016, Biden was one of few conventional Democrats to make an effort to say nice things about Sanders, even in contrast with Clinton.

This exchange with CNN's Gloria Borger in January of 2016 was an example:

BIDEN: Bernie is speaking to a yearning that is deep and real, and he has credibility on it. And that is the absolutely enormous concentration of wealth in a small group of people with the middle class being left out...

CNN: But Hillary is talking about that as well?

BIDEN: Well, it is relatively new for Hillary to talk about that...

Sanders, raised by Jewish immigrants in Brooklyn, grew up in much meaner circumstances than Biden, but their backgrounds aren't dissimilar. Biden is the son of a down-on-his-luck car dealership manager from Scranton, and has a reputation as an old-school church-and-factory man, who enjoys hanging out in diners and bowling alleys.

While reporters who cover Biden have long understood the "Scranton Joe" image to be as much caricature as reality, voters don't see it that way.

The Malcolm Gladwell/Blink response many Democrats, particularly older ones, have to Biden is that he's an affable, try-hard representative of the little guy. Biden sells himself as a "union man" who eschews the Martha's Vineyard-and-Davos image of neoliberal Democrats.

Intellectually, the Sanders campaign has pushed back. In April, after Biden displaced him from the poll lead, Bernie went on TV to talk about his policy differences with Biden.

He seemed put out that Biden kicked off his campaign with an endorsement from the International Association of Fire Fighters. Sanders, who's described his campaign as a Trade Unionist revolution, pointed to Biden's support of trademark union betrayals like NAFTA, Most Favored Nation trading status for China, and the Trans Pacific Partnership.

But Bernie hastened to remind everyone he and Biden were friends, and he would run an "issue-oriented campaign, not based on personal attacks." He has since tried repeatedly to draw civil distinctions between himself and Biden, including a July clash over health care.

In a typical example of how Biden's political style works, he trashed Bernie's Medicare for All plan in a rambling, inscrutable speech that asked audience members who'd lost loved ones to terminal illnesses to raise their hands. Then he said:

Every second counts. It's not about a year, it's about the day, the week, the month, the next six months. It's about hope. And if you have these hiatuses, it may, it may -- this may go as smooth -- as my grandpappy said -- smooth as silk. But the truth of the matter is, it's likely to be a bumpy ride...

Underneath all the homespun "grandpappy" verbiage, Biden seemed to be suggesting the Sanders plan would create coverage "hiatuses" for people who might literally die any second. Underneath the oddball messaging, it was a classic corporate scare-tactic talking point.

The Sanders camp pushed back, but Bernie still didn't name Biden when he countered soon after in a speech at George Washington University blasting "half-truths, misinformation and in some cases outright lies that are being spread about Medicare for All."

Sanders has a million volunteers, 2.5 million contributors, and a campaign-leading $27.3 million in cash on hand. His campaign is correct this week to point out that rumors of his demise are absurd. Still, he's not wildly outperforming expectations the way he did in 2016.

Some of his issues are due to coverage, like the insistence that Sanders and Warren are fighting over the same finite patch of votes, when polls increasingly show Sanders and Warren are succeeding with different groups.

Warren has made inroads among traditional Democrats and older female voters who eluded Sanders last time, suggesting that there's more support for progressive policy ideas out there than commonly believed. While Warren has votes to win among the supporters of Kamala Harris and Pete Buttigieg (whose supporters view Warren as a second choice), Bernie's immediate challenge is Biden, in particular his grip on low-income voters.

Biden's appeal is that he's a vote for a return to a kind of status quo, which should be a pitch in Bernie's wheelhouse. Sanders' campaign is based on the notion that a return even to pre-Trump norms is unsustainable - for the underinsured, for the climate, for union and non-union workers, for customers of banks, for holders of student debt, and so on.

Hillary Clinton, with her defiant "that's what they offered" response to questions about bank-funded speaking fees, made finding outrage on this front easy for Sanders. The conundrum of "Scranton Joe" is no less real, but it's been politically more difficult, and Sanders is running out of time to solve it.