SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

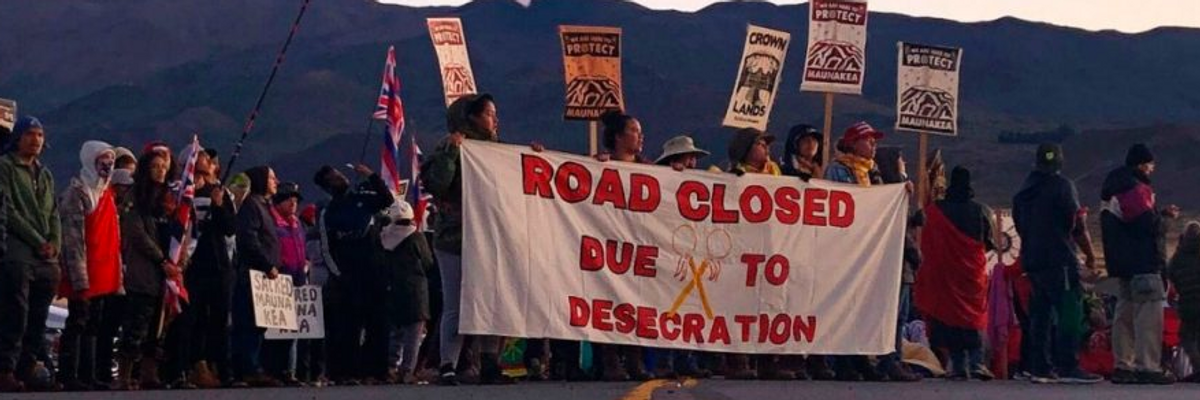

At the heart of the Mauna Kea action is thus a challenge not only to a telescope, but to capital and the pursuit of unmitigated industrial growth at any cost. (Photo: Screenshot/Washington Post)

Thousands of Native Hawaiians and their supporters have been congregating since July 15 at the base of Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano and mountain on the island of Hawaii. Known in Hawaiian as the kia'i, the protectors--a term the group prefers to "protesters"--seek to deter construction of the $1.4 billion Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), the largest telescope in the Northern Hemisphere. Business owners and state officials promise the telescope will provide jobs, educational opportunities and high-resolution astronomical imagery.

The protectors' mobilization stems from a number of concerns about the vulnerability of the mountain to the effects of a new, 18-story telescope, as well as a fight for Indigenous self-determination in the face of colonialist control. Mauna Kea is an environmentally sensitive conservation district; it's also sacred in Native Hawaiian traditions and religions, remaining one of the few bastions of Indigenous cultural preservation and sovereignty in the state.

The current demonstrations at Mauna Kea are the culmination of decades of state land mismanagement and broken promises over the mountain, dating back to 1968, when the state leased the mountain to the University of Hawaii. Since then, Mauna Kea has been prized by astronomers for its high altitude and lack of atmospheric pollution, leading to the construction of 21 telescopes within 13 observatories. The TMT would be the 22nd telescope; the Washington Post (7/18/19), Associated Press (7/16/19) and other outlets have erroneously tallied the telescopes at 13.

National media coverage of the protectors' struggle accelerated around 2014 and 2015, when the kia'ifirst assembled at Mauna Kea in opposition to the TMT, preventing its construction. Yet this reporting fell woefully short.

"In 2014 and 2015," corporate media outlets "were obsessed with this idea of science versus culture, as if our kupuna [elders] haven't practiced applied science," Kaniela Ing, a Mauna Kea protector and Hawaii Community Bail Fund manager, told FAIR. At that time, as Marisa Peryer recently noted for the Columbia Journalism Review (7/29/19), CNN (8/27/15) published an article headlined "Science and Religion Fight Over Hawaii's Highest Point."

Other coverage was outright condescending. In 2014, the New York Times (10/20/14) called the protectors' movement "creationism," ridiculing activists' claims that the telescope was a profit-seeking venture, omitting the TMT's status as an LLC funded largely by multibillionaire Intel founder Gordon Moore's philanthropic organization. The article dismissed the cooperation between Native Hawaiians and environmentalists as a "marriage of convenience," condemning the protectors for "waging skirmishes against science."

Peryer also cited a New York Times editorial (5/2/15) portraying the TMT as an innocent scapegoat caught in the middle of a battle dating back to the US's 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom. The piece lamented that "coexistence may never satisfy the core group of protesters who have been demanding the total erasure of technology from Mauna Kea's peak."

Many kia'i agree that media outlets have been more careful in recent months to avoid such facile binaries. Still, protectors face the challenges of specious narratives.

One of these relates to portrayals of public support of the TMT. A 2018 poll from the Honolulu Star-Advertiser indicated that 77 percent of respondents, and 72 percent of Native Hawaiian respondents, supported the construction of the TMT. The poll was referenced in various local and national media outlets, in addition to the Star-Advertiser: Hawaii News Now (7/21/19; 7/22/19), Hawaii Public Radio (7/29/19), AP (3/26/18), HuffPost (10/31/18) and the New York Times (7/10/19).

It's imperative, however, to consider whose opinion was sought. The Star-Advertiser surveyed a total of 800 registered voters, only 78 of whom were Native Hawaiian; notably, Native Hawaiians have historically been subjected to voter suppression. "There were all these internally invalid measures of how this poll could really have any weight," Uahikea Maile, a Mauna Kea protector and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, told FAIR. "I'm fearful of the misrepresentation, because it's obviously disproportionate to the reality of the situation."

Mischaracterization of the protectors took other forms. The Associated Press (7/16/19), for example, reported that protesters were "bullying" supporters of the telescope, a claim that the protest's organizational structure and tactics directly contradict. The story was republished on NBC News (7/17/19) and in the Washington Post, under the headline "Native Hawaiians' Protests Stop Researchers From Studying the Skies."

The Associated Press (8/10/19) propagated a similar narrative in an article headlined "Amid Protest, Astronomers Lose Observation Time." The story bemoaned astronomers' reported loss of some 2,000 hours of viewing time at Mauna Kea's existing telescopes in light of the protests. It also paraphrased astronomers' statements that the resistance had denied them "regular, guaranteed access to their facilities, which puts their staff and equipment at risk."

According to veteran Mauna Kea protector Kealoha Pisciotta, who was quoted in the Associated Press article, astronomers weren't blocked by the kia'i; rather, their employers ordered them to descend the mountain. Astronomers "haven't been blocked from the beginning. When they were allegedly blocked, it was really their own choice, because the observatories made their staffs stay down" amid the demonstrations, Pisciotta told FAIR. "They tried to argue that they were losing science because of us. How can you say it's because of us? You're the ones who ordered your people down. Not us."

Pisciotta also noted that media coverage has muted the cultural and religious significance of Mauna Kea. "For a long time, the Associated Press [7/16/19, 7/18/19], everybody," including USA Today (8/21/19), "kept using the words 'some Hawaiians'" in reference to who holds the mountain sacred. "At one point, we said, 'It's not 'some Hawaiians.' We are the majority.'"

She added that Native Hawaiians' right to ascend the mountain for "subsistence, cultural and religious purposes" is enshrined in the Hawaii State Constitution. Despite this, state government temporarily denied cultural practitioners access to the mountain in mid-July, later permitting them one vehicle to ascend the mountain per day (Big Island Video News, (8/9/19).

As the protests continue, outlets report that the kia'i and TMT supporters are at an impasse, and suggest that negotiations might allow the project to proceed on Mauna Kea (Hawaii News Now, 7/25/19; NBC News, 8/18/19; Honolulu Civil Beat, 7/31/19). "What is tragic," the aforementioned 2015 New York Times editorial cried, "is the missed opportunity for shared understanding."

While proposals to compromise might appear fair, protectors say, they dismiss the historical context in Hawaii of colonialism and the usurpation of Indigenous land that continues today. Thus, these suggestions elide the stark power asymmetry between historically disenfranchised and marginalized Native Hawaiians and the billion-dollar, state-backed TMT project.

"The point that that misses is there's not anything to negotiate. Either the Mauna is sacred or it's not. When you talk about these issues, how do you compromise that?" said Kenneth Lawson, a Mauna Kea protector and law professor at the University of Hawaii, Manoa.

"We have shared the mountain since 1968," said Pisciotta. "It's our temple, it's our church, it's our house of worship."

At the heart of the Mauna Kea action is thus a challenge not only to a telescope, but to capital and the pursuit of unmitigated industrial growth at any cost. It's no wonder, then, that when corporate-owned media are tasked with examining this movement, their limitations rear their heads.

"Is the advancement of a certain field of science worth the further disenfranchisement, the pain of a marginalized group?" asked the Bail Fund's Ing. "I think that's a valid question for the media, but [the media] scrapes the surface of what this is really about."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Thousands of Native Hawaiians and their supporters have been congregating since July 15 at the base of Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano and mountain on the island of Hawaii. Known in Hawaiian as the kia'i, the protectors--a term the group prefers to "protesters"--seek to deter construction of the $1.4 billion Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), the largest telescope in the Northern Hemisphere. Business owners and state officials promise the telescope will provide jobs, educational opportunities and high-resolution astronomical imagery.

The protectors' mobilization stems from a number of concerns about the vulnerability of the mountain to the effects of a new, 18-story telescope, as well as a fight for Indigenous self-determination in the face of colonialist control. Mauna Kea is an environmentally sensitive conservation district; it's also sacred in Native Hawaiian traditions and religions, remaining one of the few bastions of Indigenous cultural preservation and sovereignty in the state.

The current demonstrations at Mauna Kea are the culmination of decades of state land mismanagement and broken promises over the mountain, dating back to 1968, when the state leased the mountain to the University of Hawaii. Since then, Mauna Kea has been prized by astronomers for its high altitude and lack of atmospheric pollution, leading to the construction of 21 telescopes within 13 observatories. The TMT would be the 22nd telescope; the Washington Post (7/18/19), Associated Press (7/16/19) and other outlets have erroneously tallied the telescopes at 13.

National media coverage of the protectors' struggle accelerated around 2014 and 2015, when the kia'ifirst assembled at Mauna Kea in opposition to the TMT, preventing its construction. Yet this reporting fell woefully short.

"In 2014 and 2015," corporate media outlets "were obsessed with this idea of science versus culture, as if our kupuna [elders] haven't practiced applied science," Kaniela Ing, a Mauna Kea protector and Hawaii Community Bail Fund manager, told FAIR. At that time, as Marisa Peryer recently noted for the Columbia Journalism Review (7/29/19), CNN (8/27/15) published an article headlined "Science and Religion Fight Over Hawaii's Highest Point."

Other coverage was outright condescending. In 2014, the New York Times (10/20/14) called the protectors' movement "creationism," ridiculing activists' claims that the telescope was a profit-seeking venture, omitting the TMT's status as an LLC funded largely by multibillionaire Intel founder Gordon Moore's philanthropic organization. The article dismissed the cooperation between Native Hawaiians and environmentalists as a "marriage of convenience," condemning the protectors for "waging skirmishes against science."

Peryer also cited a New York Times editorial (5/2/15) portraying the TMT as an innocent scapegoat caught in the middle of a battle dating back to the US's 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom. The piece lamented that "coexistence may never satisfy the core group of protesters who have been demanding the total erasure of technology from Mauna Kea's peak."

Many kia'i agree that media outlets have been more careful in recent months to avoid such facile binaries. Still, protectors face the challenges of specious narratives.

One of these relates to portrayals of public support of the TMT. A 2018 poll from the Honolulu Star-Advertiser indicated that 77 percent of respondents, and 72 percent of Native Hawaiian respondents, supported the construction of the TMT. The poll was referenced in various local and national media outlets, in addition to the Star-Advertiser: Hawaii News Now (7/21/19; 7/22/19), Hawaii Public Radio (7/29/19), AP (3/26/18), HuffPost (10/31/18) and the New York Times (7/10/19).

It's imperative, however, to consider whose opinion was sought. The Star-Advertiser surveyed a total of 800 registered voters, only 78 of whom were Native Hawaiian; notably, Native Hawaiians have historically been subjected to voter suppression. "There were all these internally invalid measures of how this poll could really have any weight," Uahikea Maile, a Mauna Kea protector and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, told FAIR. "I'm fearful of the misrepresentation, because it's obviously disproportionate to the reality of the situation."

Mischaracterization of the protectors took other forms. The Associated Press (7/16/19), for example, reported that protesters were "bullying" supporters of the telescope, a claim that the protest's organizational structure and tactics directly contradict. The story was republished on NBC News (7/17/19) and in the Washington Post, under the headline "Native Hawaiians' Protests Stop Researchers From Studying the Skies."

The Associated Press (8/10/19) propagated a similar narrative in an article headlined "Amid Protest, Astronomers Lose Observation Time." The story bemoaned astronomers' reported loss of some 2,000 hours of viewing time at Mauna Kea's existing telescopes in light of the protests. It also paraphrased astronomers' statements that the resistance had denied them "regular, guaranteed access to their facilities, which puts their staff and equipment at risk."

According to veteran Mauna Kea protector Kealoha Pisciotta, who was quoted in the Associated Press article, astronomers weren't blocked by the kia'i; rather, their employers ordered them to descend the mountain. Astronomers "haven't been blocked from the beginning. When they were allegedly blocked, it was really their own choice, because the observatories made their staffs stay down" amid the demonstrations, Pisciotta told FAIR. "They tried to argue that they were losing science because of us. How can you say it's because of us? You're the ones who ordered your people down. Not us."

Pisciotta also noted that media coverage has muted the cultural and religious significance of Mauna Kea. "For a long time, the Associated Press [7/16/19, 7/18/19], everybody," including USA Today (8/21/19), "kept using the words 'some Hawaiians'" in reference to who holds the mountain sacred. "At one point, we said, 'It's not 'some Hawaiians.' We are the majority.'"

She added that Native Hawaiians' right to ascend the mountain for "subsistence, cultural and religious purposes" is enshrined in the Hawaii State Constitution. Despite this, state government temporarily denied cultural practitioners access to the mountain in mid-July, later permitting them one vehicle to ascend the mountain per day (Big Island Video News, (8/9/19).

As the protests continue, outlets report that the kia'i and TMT supporters are at an impasse, and suggest that negotiations might allow the project to proceed on Mauna Kea (Hawaii News Now, 7/25/19; NBC News, 8/18/19; Honolulu Civil Beat, 7/31/19). "What is tragic," the aforementioned 2015 New York Times editorial cried, "is the missed opportunity for shared understanding."

While proposals to compromise might appear fair, protectors say, they dismiss the historical context in Hawaii of colonialism and the usurpation of Indigenous land that continues today. Thus, these suggestions elide the stark power asymmetry between historically disenfranchised and marginalized Native Hawaiians and the billion-dollar, state-backed TMT project.

"The point that that misses is there's not anything to negotiate. Either the Mauna is sacred or it's not. When you talk about these issues, how do you compromise that?" said Kenneth Lawson, a Mauna Kea protector and law professor at the University of Hawaii, Manoa.

"We have shared the mountain since 1968," said Pisciotta. "It's our temple, it's our church, it's our house of worship."

At the heart of the Mauna Kea action is thus a challenge not only to a telescope, but to capital and the pursuit of unmitigated industrial growth at any cost. It's no wonder, then, that when corporate-owned media are tasked with examining this movement, their limitations rear their heads.

"Is the advancement of a certain field of science worth the further disenfranchisement, the pain of a marginalized group?" asked the Bail Fund's Ing. "I think that's a valid question for the media, but [the media] scrapes the surface of what this is really about."

Thousands of Native Hawaiians and their supporters have been congregating since July 15 at the base of Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano and mountain on the island of Hawaii. Known in Hawaiian as the kia'i, the protectors--a term the group prefers to "protesters"--seek to deter construction of the $1.4 billion Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), the largest telescope in the Northern Hemisphere. Business owners and state officials promise the telescope will provide jobs, educational opportunities and high-resolution astronomical imagery.

The protectors' mobilization stems from a number of concerns about the vulnerability of the mountain to the effects of a new, 18-story telescope, as well as a fight for Indigenous self-determination in the face of colonialist control. Mauna Kea is an environmentally sensitive conservation district; it's also sacred in Native Hawaiian traditions and religions, remaining one of the few bastions of Indigenous cultural preservation and sovereignty in the state.

The current demonstrations at Mauna Kea are the culmination of decades of state land mismanagement and broken promises over the mountain, dating back to 1968, when the state leased the mountain to the University of Hawaii. Since then, Mauna Kea has been prized by astronomers for its high altitude and lack of atmospheric pollution, leading to the construction of 21 telescopes within 13 observatories. The TMT would be the 22nd telescope; the Washington Post (7/18/19), Associated Press (7/16/19) and other outlets have erroneously tallied the telescopes at 13.

National media coverage of the protectors' struggle accelerated around 2014 and 2015, when the kia'ifirst assembled at Mauna Kea in opposition to the TMT, preventing its construction. Yet this reporting fell woefully short.

"In 2014 and 2015," corporate media outlets "were obsessed with this idea of science versus culture, as if our kupuna [elders] haven't practiced applied science," Kaniela Ing, a Mauna Kea protector and Hawaii Community Bail Fund manager, told FAIR. At that time, as Marisa Peryer recently noted for the Columbia Journalism Review (7/29/19), CNN (8/27/15) published an article headlined "Science and Religion Fight Over Hawaii's Highest Point."

Other coverage was outright condescending. In 2014, the New York Times (10/20/14) called the protectors' movement "creationism," ridiculing activists' claims that the telescope was a profit-seeking venture, omitting the TMT's status as an LLC funded largely by multibillionaire Intel founder Gordon Moore's philanthropic organization. The article dismissed the cooperation between Native Hawaiians and environmentalists as a "marriage of convenience," condemning the protectors for "waging skirmishes against science."

Peryer also cited a New York Times editorial (5/2/15) portraying the TMT as an innocent scapegoat caught in the middle of a battle dating back to the US's 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom. The piece lamented that "coexistence may never satisfy the core group of protesters who have been demanding the total erasure of technology from Mauna Kea's peak."

Many kia'i agree that media outlets have been more careful in recent months to avoid such facile binaries. Still, protectors face the challenges of specious narratives.

One of these relates to portrayals of public support of the TMT. A 2018 poll from the Honolulu Star-Advertiser indicated that 77 percent of respondents, and 72 percent of Native Hawaiian respondents, supported the construction of the TMT. The poll was referenced in various local and national media outlets, in addition to the Star-Advertiser: Hawaii News Now (7/21/19; 7/22/19), Hawaii Public Radio (7/29/19), AP (3/26/18), HuffPost (10/31/18) and the New York Times (7/10/19).

It's imperative, however, to consider whose opinion was sought. The Star-Advertiser surveyed a total of 800 registered voters, only 78 of whom were Native Hawaiian; notably, Native Hawaiians have historically been subjected to voter suppression. "There were all these internally invalid measures of how this poll could really have any weight," Uahikea Maile, a Mauna Kea protector and assistant professor at the University of Toronto, told FAIR. "I'm fearful of the misrepresentation, because it's obviously disproportionate to the reality of the situation."

Mischaracterization of the protectors took other forms. The Associated Press (7/16/19), for example, reported that protesters were "bullying" supporters of the telescope, a claim that the protest's organizational structure and tactics directly contradict. The story was republished on NBC News (7/17/19) and in the Washington Post, under the headline "Native Hawaiians' Protests Stop Researchers From Studying the Skies."

The Associated Press (8/10/19) propagated a similar narrative in an article headlined "Amid Protest, Astronomers Lose Observation Time." The story bemoaned astronomers' reported loss of some 2,000 hours of viewing time at Mauna Kea's existing telescopes in light of the protests. It also paraphrased astronomers' statements that the resistance had denied them "regular, guaranteed access to their facilities, which puts their staff and equipment at risk."

According to veteran Mauna Kea protector Kealoha Pisciotta, who was quoted in the Associated Press article, astronomers weren't blocked by the kia'i; rather, their employers ordered them to descend the mountain. Astronomers "haven't been blocked from the beginning. When they were allegedly blocked, it was really their own choice, because the observatories made their staffs stay down" amid the demonstrations, Pisciotta told FAIR. "They tried to argue that they were losing science because of us. How can you say it's because of us? You're the ones who ordered your people down. Not us."

Pisciotta also noted that media coverage has muted the cultural and religious significance of Mauna Kea. "For a long time, the Associated Press [7/16/19, 7/18/19], everybody," including USA Today (8/21/19), "kept using the words 'some Hawaiians'" in reference to who holds the mountain sacred. "At one point, we said, 'It's not 'some Hawaiians.' We are the majority.'"

She added that Native Hawaiians' right to ascend the mountain for "subsistence, cultural and religious purposes" is enshrined in the Hawaii State Constitution. Despite this, state government temporarily denied cultural practitioners access to the mountain in mid-July, later permitting them one vehicle to ascend the mountain per day (Big Island Video News, (8/9/19).

As the protests continue, outlets report that the kia'i and TMT supporters are at an impasse, and suggest that negotiations might allow the project to proceed on Mauna Kea (Hawaii News Now, 7/25/19; NBC News, 8/18/19; Honolulu Civil Beat, 7/31/19). "What is tragic," the aforementioned 2015 New York Times editorial cried, "is the missed opportunity for shared understanding."

While proposals to compromise might appear fair, protectors say, they dismiss the historical context in Hawaii of colonialism and the usurpation of Indigenous land that continues today. Thus, these suggestions elide the stark power asymmetry between historically disenfranchised and marginalized Native Hawaiians and the billion-dollar, state-backed TMT project.

"The point that that misses is there's not anything to negotiate. Either the Mauna is sacred or it's not. When you talk about these issues, how do you compromise that?" said Kenneth Lawson, a Mauna Kea protector and law professor at the University of Hawaii, Manoa.

"We have shared the mountain since 1968," said Pisciotta. "It's our temple, it's our church, it's our house of worship."

At the heart of the Mauna Kea action is thus a challenge not only to a telescope, but to capital and the pursuit of unmitigated industrial growth at any cost. It's no wonder, then, that when corporate-owned media are tasked with examining this movement, their limitations rear their heads.

"Is the advancement of a certain field of science worth the further disenfranchisement, the pain of a marginalized group?" asked the Bail Fund's Ing. "I think that's a valid question for the media, but [the media] scrapes the surface of what this is really about."