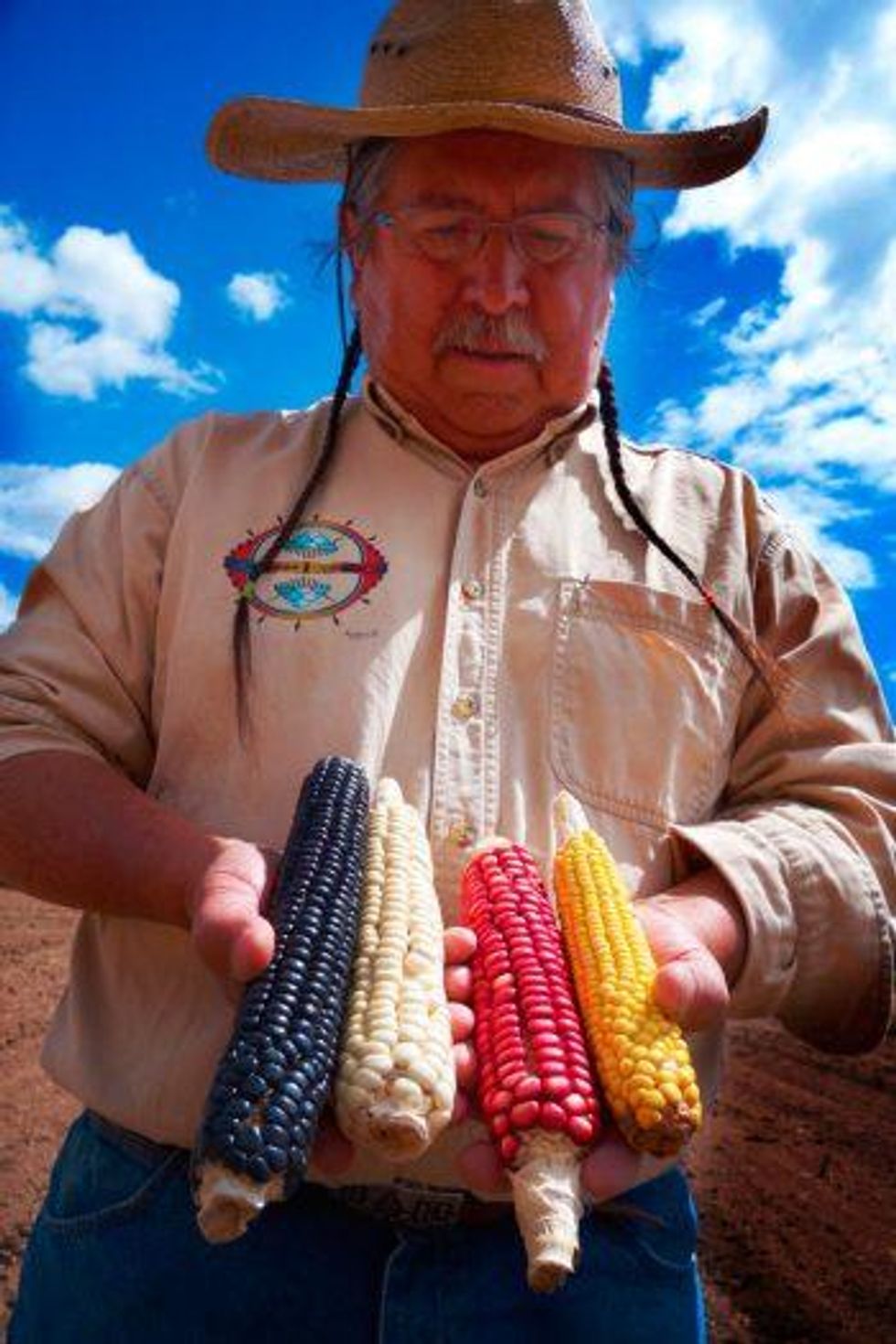

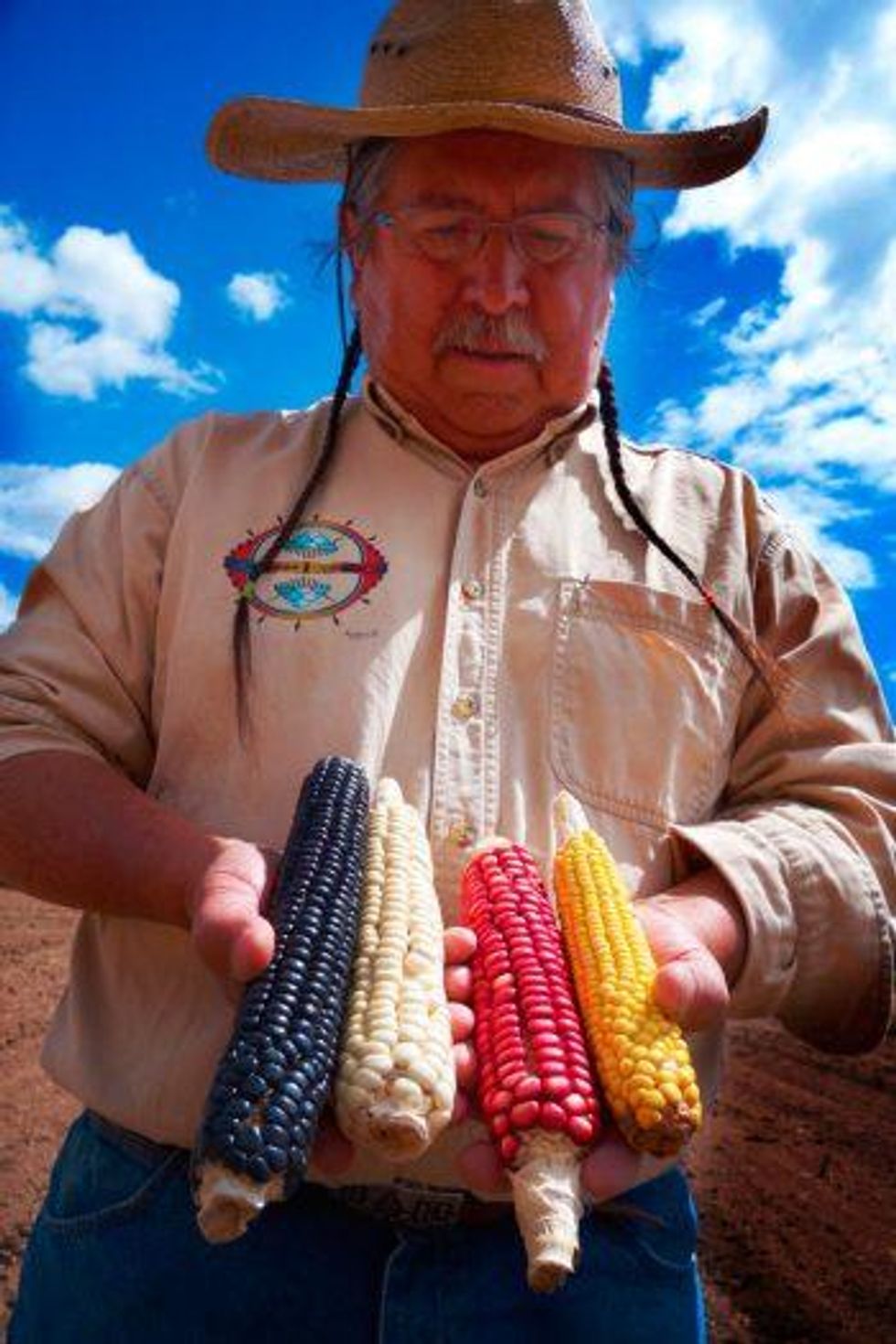

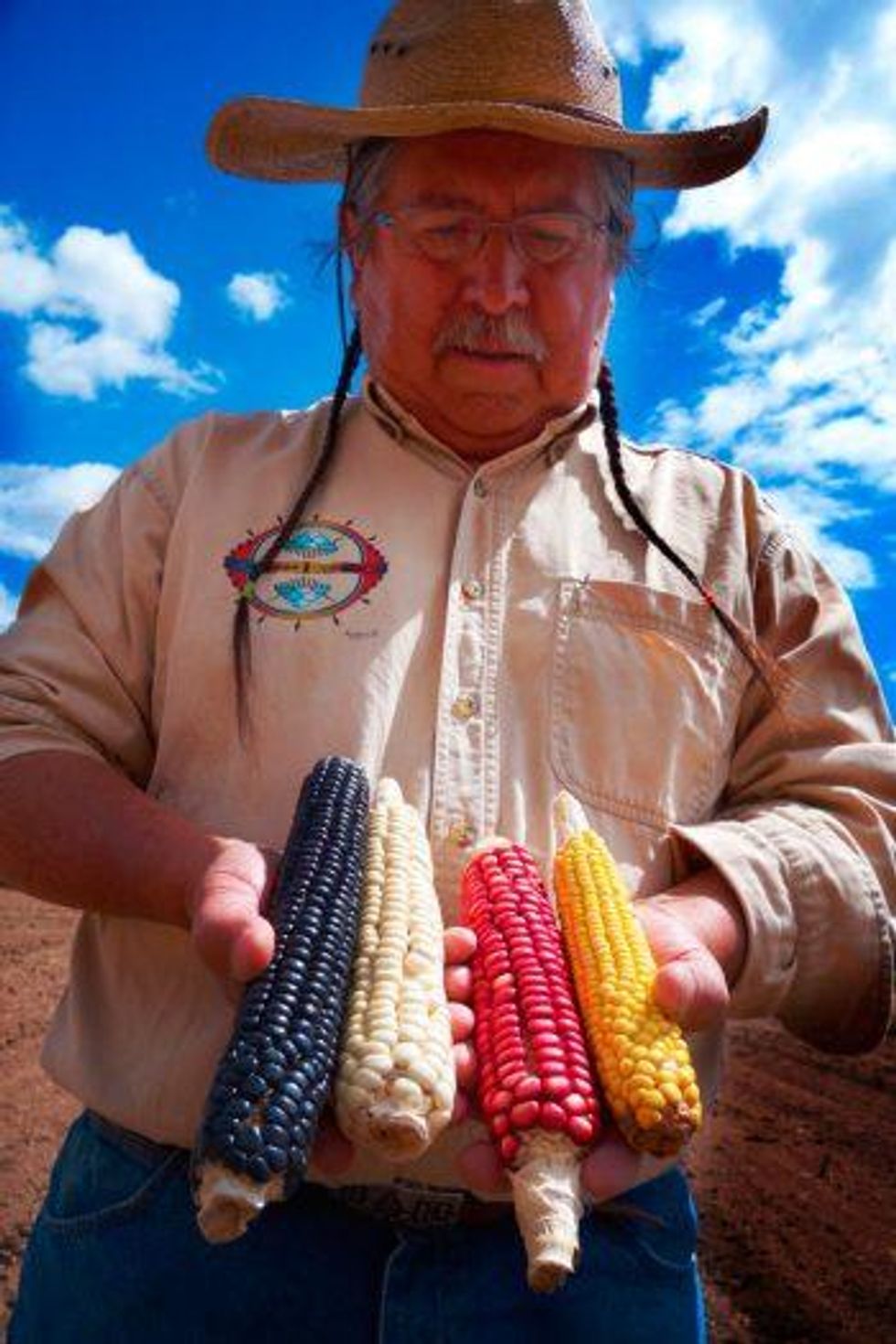

Clayton Brascoupe holds several ears of indigenous corn. (Photo: SEED: The Untold Story/Collective Eye Films via Civil Eats)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Clayton Brascoupe holds several ears of indigenous corn. (Photo: SEED: The Untold Story/Collective Eye Films via Civil Eats)

Clayton Brascoupe has farmed in the red-brown foothills of New Mexico's Sangre de Cristo Mountains for more than 45 years. A Mohawk-Anishnaabe originally from a New York reservation, Brascoupe married into the Pueblo of Tesuque tribe and has since planted at least 60 varieties of corns, beans, squashes, and other heirloom crops grown for millennia by the area's Native Americans.

For more than three decades, he has taught other indigenous farmers about sustainable agricultural practices, seed saving, healthy eating, and traditional food production. With seed diversity loss a grave concern in recent years, Brascoupe has been cataloguing the seeds stored by his own family. But earlier this spring, two of his tool sheds burned down, destroying several dozen varieties.

"I will have trouble replacing them. They may be lost for good," said Brascoupe, who runs the Traditional Native American Farmers Association.

In recent decades, Native Americans across the U.S. have rallied to bring back the traditional crops that fed their ancestors, and the seeds they need to grow them. But many traditional seeds have been lost, and many of those that are still cultivated face environmental and human threats, including poor storage facilities. Assessing seeds' history can also be challenging. And while several communities have created Native seed exchanges, seed banks, and sanctuaries, their scale is local and relatively small. Moreover, federal law, which protects tribal lands, human tissue, and cultural artifacts, is unclear when it comes to protecting Native traditional seeds--while it does shield hybrid and genetically engineered seeds.

Newly proposed legislation could help. The Native American Seeds Protection Act of 2019 would direct the Government Accountability Office to study the long-term viability of Native seeds and the programs and laws that could safeguard them. The study would assess the cultivation, harvesting, storage, and commercialization of these ancient seeds, as well as investigate the fraudulent marketing of seeds as "traditional" or "produced by Native Americans."

The six senators who introduced the bipartisan, bicameral bill all hope the effort will "support healthcare, food security, and economic development in tribal communities."

The legislation is a step forward, Brascoupe said. Native people urgently need to inventory the seeds they still have, interview elders about rare, old varieties, and create community and regional seed libraries and backup seed banks. "A seed represents potential and wealth," he said. "There are thousands of older varieties with different strengths and flavors. My priority is keeping that diversity."

To Native Americans, seed protection isn't just about maintaining diverse genetics and food sustainability, said Lea Zeise, a regional representative for the Intertribal Agriculture Council and a farmer who runs a corn growing cooperative on her reservation. "We need to know about protecting our seeds and foods... to protect the sacredness of our culture," she added .

Seeds hold spiritual symbolism, Zeise said, because Native people view them as physical relatives or ancestors.

"They're not inanimate objects for us," Zeise said. "The word for corn, o*n^ste?, is closely related to the word for breastmilk. That's how intimate a relationship it is, and how closely we're connected."

Several years ago, when Zeise visited a Haudenosaunee community, her hosts sent her to a white farmer to buy the sacred Tuscarora White Corn. That's when Zeise, a member of the Oneida Nation--also part of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy--realized Native Americans were losing control of the ancient plants that had once sustained them.

White corn had nearly disappeared from her tribe's Wisconsin reservation. Much of the land was owned or leased by non-Native farmers growing conventional, genetically modified corn. And while tribal seed keepers had maintained subsistence plots for decades, most Oneida members no longer knew how to plant, harvest, or hull the traditional crop--nor how to save its seeds.

"We had an awakening and realized that we had to act quickly," said Zeise. "There aren't many experienced Native growers left, and we felt that our foods need to be grown by us because we know how to sing for them, hold ceremony for them, and maintain that relationship. When others plant our seeds, they see them as simple inputs to their system."

But the Oneida people of Wisconsin lacked the seeds to start growing white corn--a challenge because Native seeds are not typically bought in stores or from catalogs but gifted and traded among family and community members. Eventually, Zeise traveled thousands of miles to trade wild rice for corn seeds with the Onondaga Nation in New York state, whose members also taught her how to plant and harvest the corn.

To help her community regain a relationship with the corn and safeguard its seeds for future generations, Zeise and her mother started a cooperative called Ohe*laku, which means "among the corn stalks." Over the past four years, 20 families have grown the crop on six acres.

Along with community volunteers, they harvest the ears by hand, then husk and braid them and hang them to dry in a barn. In the springtime, the seeds are shelled and ready to be cooked or ground into flour, and turned into posole (hominy soup), cornbread, or Kan^stohale bread. Some of the seeds are set aside to be planted. Zeise's cooperative now shares and gifts both the corn and its seeds to people within the Oneida tribe and others.

Cooperative members also participate in Braiding the Sacred, a series of regional gatherings that bring Native corn growers to harvest together, exchange seeds and stories, offer mutual encouragement, and talk about the threats facing sacred corn.

Braiding the Sacred also rematriates seeds to other trusted communities to help Native people re-learn to grow them. It's frowned upon in the Native community to sell or buy seeds, and one must be very careful about who they share them with, said Zeise. "You need to have a relationship with that person, to understand what his or her intentions are. You're handing off a relative, so it's not something that's done lightly."

Advocates like Zeise say indigenous seeds need protecting because they've been co-opted by businesses and corporations in the name of profit.

Some seed exchanges and catalogs sell varieties they claim are "traditional," "ceremonial," and Native American in origin. If that were the case, said Zeise, "there's no way that a tribe would allow them to be sold in a catalog."

The fact that agrochemical companies and seed breeders have altered ancient seeds' biology to produce hybrid and genetically engineered (GE) varieties is deeply offensive to Native tribes, she added.

"When we hear about someone taking seeds into a lab, pulling them apart, and manipulating their genes... this does not sit well with our community," she said.

Bioengineered and hybrid varieties also threaten to contaminate the traditional seeds still held and grown by Native people. Native farmers who plant corn too close to commercial fields may expose their crops to cross-pollination by GE and patented seeds (and could be opening themselves up to lawsuits). In Mexico, corn's place of origin, GE crops have been banned after studies found that GE corn had contaminated traditional varieties.

And in Minnesota, where members of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe still harvest wild rice on the state's lakes by hand, the University of Minnesota helped develop commercial varieties that Minnesota and California farmers grow in flooded fields. After the university's scientists announced they had mapped a portion of the wild rice genome, the tribe successfully pushed for a state law that prohibits the introduction of any genetically engineered wild rice paddy stands without a full environmental impact assessment.

Protecting traditional varieties is critical, said Brascoupe of the Traditional Native American Farmers Association, not just because of their cultural and spiritual significance. They're nutritionally superior and can help fight the epidemic of obesity in Indian Country and across the U.S., he said. They can also better withstand extreme weather events such as droughts, making them more resilient to climate change and valuable to all farmers.

"These older varieties have traits that can handle all sorts of environmental changes and challenges," said Brascoupe, whose organization participates in seed exchanges and runs trainings on the risk of contamination with GE seeds. The group has helped pass a tribal resolution in support of seed sovereignty and a state memorial recognizing the significance of Native seeds. "We need to educate people about their loss. Many have been around for millennia and once they're contaminated or lost, there is no place we can go back to get them."

Brascoupe recalled the recent case of a white farmer selling so-called traditional Hopi corn in the pueblo communities. "The corn looked similar (to Hopi corn), but we were concerned about its origins and whether it was not contaminated with GE corn," he said. "We asked him to not come to our pueblo to sell anymore."

The loss of seeds is yet another injustice in the long history of discrimination and abuse Native Americans have faced over the last two hundred years, said Joy Hought, the executive director of Native Seeds/SEARCH, a nonprofit that banks and distributes heirloom seeds traditionally grown by indigenous communities in the Southwest.

Like the cancer cells of Henrietta Lacks used for decades by researchers and biotech companies, ancient seeds have been commodified, multiplied, and turned into profit. And while the Convention on Biological Diversity, an international, legally binding treaty that's supposed to ensure that the benefits produced by biodiversity are shared equitably, the ideal is not reflected in reality. "Beyond cultural theft, there's economic theft. Corporations take seeds, turn them into hybrids or GMOs and somebody makes a billion dollars," said Hought.

Protecting Native American seeds won't be easy, though, said Hought, because most modern agriculture is heavily dependent on proprietary industrial seeds and the legal system is tilted in favor of protecting them.

Over the past century, the U.S. has lost about 93 percent of its food seed variety. The industry is controlled by just four corporations--Bayer, Corteva, ChemChina, and BASF--and the vast majority of the seeds planted across the U.S. are hybrid and GE, herbicide-tolerant and insect-resistant. In 2019, GE seed was planted on 92 percent of U.S. corn acres, 98 percent of U.S. cotton acres, and 94 percent of U.S. soybean acres. And since 1996, when patented, GE seeds were first commercialized, the corporations have aggressively defended their intellectual property rights.

In 1970, the Plant Variety Protection Act granted patent-like protection to sexually reproduced plant varieties, those propagated by seed, though it allowed farmers to save the seeds for their own use. More recently, utility patents (patents for inventions) have been granted for living organisms and plants, including newly developed seed varieties. Farmers cannot save seeds protected under such patents. The U.S. Supreme Court in 2001 reaffirmed that new plant breeds are indeed patentable. Because of these rules, most farmers have stopped saving and replanting seeds and must buy new seeds every year.

Meanwhile, large seed breeders are working within a narrower and narrower niche of diversity, trying to eke out a last drop of what makes a variety distinct. The marketed varieties will all be nearly identical, even if each is protected by a patent, said Hought.

Ancient seed varieties are just the opposite; they're paragons of biodiversity and that's what makes them so invaluable. Called landraces, the oldest crop cultivars domesticated by farmers from wild populations come from diverse genetics that adapted over time to suit a local environment and climate. Landrace seeds have never been formally improved through plant breeding, though they developed their unique characteristics through individual grower selection. Some of the landrace seeds, those that have been selectively bred for a few traits and consistently passed down through generations, are called heirloom (they tend to be less genetically diverse than landraces because they are more in-bred).

The genetic diversity and adaptability that make landrace and heirloom seeds so desirable also make their legal protection challenging. "If you want to protect seeds, you need to be able to confirm their identity. And, at this point in history, for many traditional varieties it's very difficult to say what their identities are," said Hought. "Biological differences make it more difficult to assess and assign a single identity to an heirloom seed, compared to, say, a hybrid or GMO variety."

It's difficult to ascertain traditional seeds' origins because farmers collect seeds from multiple plants and pull them together, resulting in a genetic mixture. Then over millennia, the seeds drift, are shared by thousands of people, and genetically adapt to different environments.

Seeds are also part of subjective cultural narratives such as creation stories, which may not always reflect historical realities. "Many seeds come out of the oral tradition," said Hought. "And human cultures and their narratives are not fixed in time, they evolve."

If two nearby farmers shared the same seeds hundreds of years ago, but gave different names to their varieties, who gets to claim it? "It's hard to ... definitively say that this seed came from the Hopi people or the Navajo people when thousands of years have transpired," Hought added.

But Zeise of the Oneida Nation said Native people share common knowledge about their ancient seeds and foods. Every tribe has its own seed varieties and Native farmers can identify their characteristics. "How would you know this is an acorn squash? Everyone knows."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Clayton Brascoupe has farmed in the red-brown foothills of New Mexico's Sangre de Cristo Mountains for more than 45 years. A Mohawk-Anishnaabe originally from a New York reservation, Brascoupe married into the Pueblo of Tesuque tribe and has since planted at least 60 varieties of corns, beans, squashes, and other heirloom crops grown for millennia by the area's Native Americans.

For more than three decades, he has taught other indigenous farmers about sustainable agricultural practices, seed saving, healthy eating, and traditional food production. With seed diversity loss a grave concern in recent years, Brascoupe has been cataloguing the seeds stored by his own family. But earlier this spring, two of his tool sheds burned down, destroying several dozen varieties.

"I will have trouble replacing them. They may be lost for good," said Brascoupe, who runs the Traditional Native American Farmers Association.

In recent decades, Native Americans across the U.S. have rallied to bring back the traditional crops that fed their ancestors, and the seeds they need to grow them. But many traditional seeds have been lost, and many of those that are still cultivated face environmental and human threats, including poor storage facilities. Assessing seeds' history can also be challenging. And while several communities have created Native seed exchanges, seed banks, and sanctuaries, their scale is local and relatively small. Moreover, federal law, which protects tribal lands, human tissue, and cultural artifacts, is unclear when it comes to protecting Native traditional seeds--while it does shield hybrid and genetically engineered seeds.

Newly proposed legislation could help. The Native American Seeds Protection Act of 2019 would direct the Government Accountability Office to study the long-term viability of Native seeds and the programs and laws that could safeguard them. The study would assess the cultivation, harvesting, storage, and commercialization of these ancient seeds, as well as investigate the fraudulent marketing of seeds as "traditional" or "produced by Native Americans."

The six senators who introduced the bipartisan, bicameral bill all hope the effort will "support healthcare, food security, and economic development in tribal communities."

The legislation is a step forward, Brascoupe said. Native people urgently need to inventory the seeds they still have, interview elders about rare, old varieties, and create community and regional seed libraries and backup seed banks. "A seed represents potential and wealth," he said. "There are thousands of older varieties with different strengths and flavors. My priority is keeping that diversity."

To Native Americans, seed protection isn't just about maintaining diverse genetics and food sustainability, said Lea Zeise, a regional representative for the Intertribal Agriculture Council and a farmer who runs a corn growing cooperative on her reservation. "We need to know about protecting our seeds and foods... to protect the sacredness of our culture," she added .

Seeds hold spiritual symbolism, Zeise said, because Native people view them as physical relatives or ancestors.

"They're not inanimate objects for us," Zeise said. "The word for corn, o*n^ste?, is closely related to the word for breastmilk. That's how intimate a relationship it is, and how closely we're connected."

Several years ago, when Zeise visited a Haudenosaunee community, her hosts sent her to a white farmer to buy the sacred Tuscarora White Corn. That's when Zeise, a member of the Oneida Nation--also part of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy--realized Native Americans were losing control of the ancient plants that had once sustained them.

White corn had nearly disappeared from her tribe's Wisconsin reservation. Much of the land was owned or leased by non-Native farmers growing conventional, genetically modified corn. And while tribal seed keepers had maintained subsistence plots for decades, most Oneida members no longer knew how to plant, harvest, or hull the traditional crop--nor how to save its seeds.

"We had an awakening and realized that we had to act quickly," said Zeise. "There aren't many experienced Native growers left, and we felt that our foods need to be grown by us because we know how to sing for them, hold ceremony for them, and maintain that relationship. When others plant our seeds, they see them as simple inputs to their system."

But the Oneida people of Wisconsin lacked the seeds to start growing white corn--a challenge because Native seeds are not typically bought in stores or from catalogs but gifted and traded among family and community members. Eventually, Zeise traveled thousands of miles to trade wild rice for corn seeds with the Onondaga Nation in New York state, whose members also taught her how to plant and harvest the corn.

To help her community regain a relationship with the corn and safeguard its seeds for future generations, Zeise and her mother started a cooperative called Ohe*laku, which means "among the corn stalks." Over the past four years, 20 families have grown the crop on six acres.

Along with community volunteers, they harvest the ears by hand, then husk and braid them and hang them to dry in a barn. In the springtime, the seeds are shelled and ready to be cooked or ground into flour, and turned into posole (hominy soup), cornbread, or Kan^stohale bread. Some of the seeds are set aside to be planted. Zeise's cooperative now shares and gifts both the corn and its seeds to people within the Oneida tribe and others.

Cooperative members also participate in Braiding the Sacred, a series of regional gatherings that bring Native corn growers to harvest together, exchange seeds and stories, offer mutual encouragement, and talk about the threats facing sacred corn.

Braiding the Sacred also rematriates seeds to other trusted communities to help Native people re-learn to grow them. It's frowned upon in the Native community to sell or buy seeds, and one must be very careful about who they share them with, said Zeise. "You need to have a relationship with that person, to understand what his or her intentions are. You're handing off a relative, so it's not something that's done lightly."

Advocates like Zeise say indigenous seeds need protecting because they've been co-opted by businesses and corporations in the name of profit.

Some seed exchanges and catalogs sell varieties they claim are "traditional," "ceremonial," and Native American in origin. If that were the case, said Zeise, "there's no way that a tribe would allow them to be sold in a catalog."

The fact that agrochemical companies and seed breeders have altered ancient seeds' biology to produce hybrid and genetically engineered (GE) varieties is deeply offensive to Native tribes, she added.

"When we hear about someone taking seeds into a lab, pulling them apart, and manipulating their genes... this does not sit well with our community," she said.

Bioengineered and hybrid varieties also threaten to contaminate the traditional seeds still held and grown by Native people. Native farmers who plant corn too close to commercial fields may expose their crops to cross-pollination by GE and patented seeds (and could be opening themselves up to lawsuits). In Mexico, corn's place of origin, GE crops have been banned after studies found that GE corn had contaminated traditional varieties.

And in Minnesota, where members of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe still harvest wild rice on the state's lakes by hand, the University of Minnesota helped develop commercial varieties that Minnesota and California farmers grow in flooded fields. After the university's scientists announced they had mapped a portion of the wild rice genome, the tribe successfully pushed for a state law that prohibits the introduction of any genetically engineered wild rice paddy stands without a full environmental impact assessment.

Protecting traditional varieties is critical, said Brascoupe of the Traditional Native American Farmers Association, not just because of their cultural and spiritual significance. They're nutritionally superior and can help fight the epidemic of obesity in Indian Country and across the U.S., he said. They can also better withstand extreme weather events such as droughts, making them more resilient to climate change and valuable to all farmers.

"These older varieties have traits that can handle all sorts of environmental changes and challenges," said Brascoupe, whose organization participates in seed exchanges and runs trainings on the risk of contamination with GE seeds. The group has helped pass a tribal resolution in support of seed sovereignty and a state memorial recognizing the significance of Native seeds. "We need to educate people about their loss. Many have been around for millennia and once they're contaminated or lost, there is no place we can go back to get them."

Brascoupe recalled the recent case of a white farmer selling so-called traditional Hopi corn in the pueblo communities. "The corn looked similar (to Hopi corn), but we were concerned about its origins and whether it was not contaminated with GE corn," he said. "We asked him to not come to our pueblo to sell anymore."

The loss of seeds is yet another injustice in the long history of discrimination and abuse Native Americans have faced over the last two hundred years, said Joy Hought, the executive director of Native Seeds/SEARCH, a nonprofit that banks and distributes heirloom seeds traditionally grown by indigenous communities in the Southwest.

Like the cancer cells of Henrietta Lacks used for decades by researchers and biotech companies, ancient seeds have been commodified, multiplied, and turned into profit. And while the Convention on Biological Diversity, an international, legally binding treaty that's supposed to ensure that the benefits produced by biodiversity are shared equitably, the ideal is not reflected in reality. "Beyond cultural theft, there's economic theft. Corporations take seeds, turn them into hybrids or GMOs and somebody makes a billion dollars," said Hought.

Protecting Native American seeds won't be easy, though, said Hought, because most modern agriculture is heavily dependent on proprietary industrial seeds and the legal system is tilted in favor of protecting them.

Over the past century, the U.S. has lost about 93 percent of its food seed variety. The industry is controlled by just four corporations--Bayer, Corteva, ChemChina, and BASF--and the vast majority of the seeds planted across the U.S. are hybrid and GE, herbicide-tolerant and insect-resistant. In 2019, GE seed was planted on 92 percent of U.S. corn acres, 98 percent of U.S. cotton acres, and 94 percent of U.S. soybean acres. And since 1996, when patented, GE seeds were first commercialized, the corporations have aggressively defended their intellectual property rights.

In 1970, the Plant Variety Protection Act granted patent-like protection to sexually reproduced plant varieties, those propagated by seed, though it allowed farmers to save the seeds for their own use. More recently, utility patents (patents for inventions) have been granted for living organisms and plants, including newly developed seed varieties. Farmers cannot save seeds protected under such patents. The U.S. Supreme Court in 2001 reaffirmed that new plant breeds are indeed patentable. Because of these rules, most farmers have stopped saving and replanting seeds and must buy new seeds every year.

Meanwhile, large seed breeders are working within a narrower and narrower niche of diversity, trying to eke out a last drop of what makes a variety distinct. The marketed varieties will all be nearly identical, even if each is protected by a patent, said Hought.

Ancient seed varieties are just the opposite; they're paragons of biodiversity and that's what makes them so invaluable. Called landraces, the oldest crop cultivars domesticated by farmers from wild populations come from diverse genetics that adapted over time to suit a local environment and climate. Landrace seeds have never been formally improved through plant breeding, though they developed their unique characteristics through individual grower selection. Some of the landrace seeds, those that have been selectively bred for a few traits and consistently passed down through generations, are called heirloom (they tend to be less genetically diverse than landraces because they are more in-bred).

The genetic diversity and adaptability that make landrace and heirloom seeds so desirable also make their legal protection challenging. "If you want to protect seeds, you need to be able to confirm their identity. And, at this point in history, for many traditional varieties it's very difficult to say what their identities are," said Hought. "Biological differences make it more difficult to assess and assign a single identity to an heirloom seed, compared to, say, a hybrid or GMO variety."

It's difficult to ascertain traditional seeds' origins because farmers collect seeds from multiple plants and pull them together, resulting in a genetic mixture. Then over millennia, the seeds drift, are shared by thousands of people, and genetically adapt to different environments.

Seeds are also part of subjective cultural narratives such as creation stories, which may not always reflect historical realities. "Many seeds come out of the oral tradition," said Hought. "And human cultures and their narratives are not fixed in time, they evolve."

If two nearby farmers shared the same seeds hundreds of years ago, but gave different names to their varieties, who gets to claim it? "It's hard to ... definitively say that this seed came from the Hopi people or the Navajo people when thousands of years have transpired," Hought added.

But Zeise of the Oneida Nation said Native people share common knowledge about their ancient seeds and foods. Every tribe has its own seed varieties and Native farmers can identify their characteristics. "How would you know this is an acorn squash? Everyone knows."

Clayton Brascoupe has farmed in the red-brown foothills of New Mexico's Sangre de Cristo Mountains for more than 45 years. A Mohawk-Anishnaabe originally from a New York reservation, Brascoupe married into the Pueblo of Tesuque tribe and has since planted at least 60 varieties of corns, beans, squashes, and other heirloom crops grown for millennia by the area's Native Americans.

For more than three decades, he has taught other indigenous farmers about sustainable agricultural practices, seed saving, healthy eating, and traditional food production. With seed diversity loss a grave concern in recent years, Brascoupe has been cataloguing the seeds stored by his own family. But earlier this spring, two of his tool sheds burned down, destroying several dozen varieties.

"I will have trouble replacing them. They may be lost for good," said Brascoupe, who runs the Traditional Native American Farmers Association.

In recent decades, Native Americans across the U.S. have rallied to bring back the traditional crops that fed their ancestors, and the seeds they need to grow them. But many traditional seeds have been lost, and many of those that are still cultivated face environmental and human threats, including poor storage facilities. Assessing seeds' history can also be challenging. And while several communities have created Native seed exchanges, seed banks, and sanctuaries, their scale is local and relatively small. Moreover, federal law, which protects tribal lands, human tissue, and cultural artifacts, is unclear when it comes to protecting Native traditional seeds--while it does shield hybrid and genetically engineered seeds.

Newly proposed legislation could help. The Native American Seeds Protection Act of 2019 would direct the Government Accountability Office to study the long-term viability of Native seeds and the programs and laws that could safeguard them. The study would assess the cultivation, harvesting, storage, and commercialization of these ancient seeds, as well as investigate the fraudulent marketing of seeds as "traditional" or "produced by Native Americans."

The six senators who introduced the bipartisan, bicameral bill all hope the effort will "support healthcare, food security, and economic development in tribal communities."

The legislation is a step forward, Brascoupe said. Native people urgently need to inventory the seeds they still have, interview elders about rare, old varieties, and create community and regional seed libraries and backup seed banks. "A seed represents potential and wealth," he said. "There are thousands of older varieties with different strengths and flavors. My priority is keeping that diversity."

To Native Americans, seed protection isn't just about maintaining diverse genetics and food sustainability, said Lea Zeise, a regional representative for the Intertribal Agriculture Council and a farmer who runs a corn growing cooperative on her reservation. "We need to know about protecting our seeds and foods... to protect the sacredness of our culture," she added .

Seeds hold spiritual symbolism, Zeise said, because Native people view them as physical relatives or ancestors.

"They're not inanimate objects for us," Zeise said. "The word for corn, o*n^ste?, is closely related to the word for breastmilk. That's how intimate a relationship it is, and how closely we're connected."

Several years ago, when Zeise visited a Haudenosaunee community, her hosts sent her to a white farmer to buy the sacred Tuscarora White Corn. That's when Zeise, a member of the Oneida Nation--also part of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy--realized Native Americans were losing control of the ancient plants that had once sustained them.

White corn had nearly disappeared from her tribe's Wisconsin reservation. Much of the land was owned or leased by non-Native farmers growing conventional, genetically modified corn. And while tribal seed keepers had maintained subsistence plots for decades, most Oneida members no longer knew how to plant, harvest, or hull the traditional crop--nor how to save its seeds.

"We had an awakening and realized that we had to act quickly," said Zeise. "There aren't many experienced Native growers left, and we felt that our foods need to be grown by us because we know how to sing for them, hold ceremony for them, and maintain that relationship. When others plant our seeds, they see them as simple inputs to their system."

But the Oneida people of Wisconsin lacked the seeds to start growing white corn--a challenge because Native seeds are not typically bought in stores or from catalogs but gifted and traded among family and community members. Eventually, Zeise traveled thousands of miles to trade wild rice for corn seeds with the Onondaga Nation in New York state, whose members also taught her how to plant and harvest the corn.

To help her community regain a relationship with the corn and safeguard its seeds for future generations, Zeise and her mother started a cooperative called Ohe*laku, which means "among the corn stalks." Over the past four years, 20 families have grown the crop on six acres.

Along with community volunteers, they harvest the ears by hand, then husk and braid them and hang them to dry in a barn. In the springtime, the seeds are shelled and ready to be cooked or ground into flour, and turned into posole (hominy soup), cornbread, or Kan^stohale bread. Some of the seeds are set aside to be planted. Zeise's cooperative now shares and gifts both the corn and its seeds to people within the Oneida tribe and others.

Cooperative members also participate in Braiding the Sacred, a series of regional gatherings that bring Native corn growers to harvest together, exchange seeds and stories, offer mutual encouragement, and talk about the threats facing sacred corn.

Braiding the Sacred also rematriates seeds to other trusted communities to help Native people re-learn to grow them. It's frowned upon in the Native community to sell or buy seeds, and one must be very careful about who they share them with, said Zeise. "You need to have a relationship with that person, to understand what his or her intentions are. You're handing off a relative, so it's not something that's done lightly."

Advocates like Zeise say indigenous seeds need protecting because they've been co-opted by businesses and corporations in the name of profit.

Some seed exchanges and catalogs sell varieties they claim are "traditional," "ceremonial," and Native American in origin. If that were the case, said Zeise, "there's no way that a tribe would allow them to be sold in a catalog."

The fact that agrochemical companies and seed breeders have altered ancient seeds' biology to produce hybrid and genetically engineered (GE) varieties is deeply offensive to Native tribes, she added.

"When we hear about someone taking seeds into a lab, pulling them apart, and manipulating their genes... this does not sit well with our community," she said.

Bioengineered and hybrid varieties also threaten to contaminate the traditional seeds still held and grown by Native people. Native farmers who plant corn too close to commercial fields may expose their crops to cross-pollination by GE and patented seeds (and could be opening themselves up to lawsuits). In Mexico, corn's place of origin, GE crops have been banned after studies found that GE corn had contaminated traditional varieties.

And in Minnesota, where members of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe still harvest wild rice on the state's lakes by hand, the University of Minnesota helped develop commercial varieties that Minnesota and California farmers grow in flooded fields. After the university's scientists announced they had mapped a portion of the wild rice genome, the tribe successfully pushed for a state law that prohibits the introduction of any genetically engineered wild rice paddy stands without a full environmental impact assessment.

Protecting traditional varieties is critical, said Brascoupe of the Traditional Native American Farmers Association, not just because of their cultural and spiritual significance. They're nutritionally superior and can help fight the epidemic of obesity in Indian Country and across the U.S., he said. They can also better withstand extreme weather events such as droughts, making them more resilient to climate change and valuable to all farmers.

"These older varieties have traits that can handle all sorts of environmental changes and challenges," said Brascoupe, whose organization participates in seed exchanges and runs trainings on the risk of contamination with GE seeds. The group has helped pass a tribal resolution in support of seed sovereignty and a state memorial recognizing the significance of Native seeds. "We need to educate people about their loss. Many have been around for millennia and once they're contaminated or lost, there is no place we can go back to get them."

Brascoupe recalled the recent case of a white farmer selling so-called traditional Hopi corn in the pueblo communities. "The corn looked similar (to Hopi corn), but we were concerned about its origins and whether it was not contaminated with GE corn," he said. "We asked him to not come to our pueblo to sell anymore."

The loss of seeds is yet another injustice in the long history of discrimination and abuse Native Americans have faced over the last two hundred years, said Joy Hought, the executive director of Native Seeds/SEARCH, a nonprofit that banks and distributes heirloom seeds traditionally grown by indigenous communities in the Southwest.

Like the cancer cells of Henrietta Lacks used for decades by researchers and biotech companies, ancient seeds have been commodified, multiplied, and turned into profit. And while the Convention on Biological Diversity, an international, legally binding treaty that's supposed to ensure that the benefits produced by biodiversity are shared equitably, the ideal is not reflected in reality. "Beyond cultural theft, there's economic theft. Corporations take seeds, turn them into hybrids or GMOs and somebody makes a billion dollars," said Hought.

Protecting Native American seeds won't be easy, though, said Hought, because most modern agriculture is heavily dependent on proprietary industrial seeds and the legal system is tilted in favor of protecting them.

Over the past century, the U.S. has lost about 93 percent of its food seed variety. The industry is controlled by just four corporations--Bayer, Corteva, ChemChina, and BASF--and the vast majority of the seeds planted across the U.S. are hybrid and GE, herbicide-tolerant and insect-resistant. In 2019, GE seed was planted on 92 percent of U.S. corn acres, 98 percent of U.S. cotton acres, and 94 percent of U.S. soybean acres. And since 1996, when patented, GE seeds were first commercialized, the corporations have aggressively defended their intellectual property rights.

In 1970, the Plant Variety Protection Act granted patent-like protection to sexually reproduced plant varieties, those propagated by seed, though it allowed farmers to save the seeds for their own use. More recently, utility patents (patents for inventions) have been granted for living organisms and plants, including newly developed seed varieties. Farmers cannot save seeds protected under such patents. The U.S. Supreme Court in 2001 reaffirmed that new plant breeds are indeed patentable. Because of these rules, most farmers have stopped saving and replanting seeds and must buy new seeds every year.

Meanwhile, large seed breeders are working within a narrower and narrower niche of diversity, trying to eke out a last drop of what makes a variety distinct. The marketed varieties will all be nearly identical, even if each is protected by a patent, said Hought.

Ancient seed varieties are just the opposite; they're paragons of biodiversity and that's what makes them so invaluable. Called landraces, the oldest crop cultivars domesticated by farmers from wild populations come from diverse genetics that adapted over time to suit a local environment and climate. Landrace seeds have never been formally improved through plant breeding, though they developed their unique characteristics through individual grower selection. Some of the landrace seeds, those that have been selectively bred for a few traits and consistently passed down through generations, are called heirloom (they tend to be less genetically diverse than landraces because they are more in-bred).

The genetic diversity and adaptability that make landrace and heirloom seeds so desirable also make their legal protection challenging. "If you want to protect seeds, you need to be able to confirm their identity. And, at this point in history, for many traditional varieties it's very difficult to say what their identities are," said Hought. "Biological differences make it more difficult to assess and assign a single identity to an heirloom seed, compared to, say, a hybrid or GMO variety."

It's difficult to ascertain traditional seeds' origins because farmers collect seeds from multiple plants and pull them together, resulting in a genetic mixture. Then over millennia, the seeds drift, are shared by thousands of people, and genetically adapt to different environments.

Seeds are also part of subjective cultural narratives such as creation stories, which may not always reflect historical realities. "Many seeds come out of the oral tradition," said Hought. "And human cultures and their narratives are not fixed in time, they evolve."

If two nearby farmers shared the same seeds hundreds of years ago, but gave different names to their varieties, who gets to claim it? "It's hard to ... definitively say that this seed came from the Hopi people or the Navajo people when thousands of years have transpired," Hought added.

But Zeise of the Oneida Nation said Native people share common knowledge about their ancient seeds and foods. Every tribe has its own seed varieties and Native farmers can identify their characteristics. "How would you know this is an acorn squash? Everyone knows."