Multinational corporations based in Europe have accelerated their foreign direct investment in the Southern states of the United States in the past quarter-century. Some companies honor workers' freedom of association, respect workers' organizing rights and engage in good-faith collective bargaining when workers choose trade union representation. Other firms have interfered with freedom of association, launched aggressive campaigns against employees' organizing attempts and failed to bargain in good faith when workers choose union representation.

A new AFL-CIO report I authored examines European companies' choices on workers' organizing rights with documented case studies in several American Southern states.

Well-known companies like VW, Airbus, IKEA, and large but lesser known ones like Fresenius and Skanska provide examples of companies that have followed a lower standard in their operations in the southern states where the region's legacy of racial injustice and social inequality open the door to a low-road way of doing business. The report also makes clear that companies always have a choice and could choose to respect workers human rights.

In their home countries, European companies investing in the American South generally respect workers' organizing and bargaining rights. They commit themselves to International Labor Organization core labor standards, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Guidelines, UN Guiding Principles, the UN Global Compact, and other international norms on freedom of association and collective bargaining. But they do not always live up to these global standards in their Southern U.S. operations.

Two different scenarios may explain the contradiction between word and deed. In one, top European company management may indeed be hostile to trade unions and would prefer to operate "union free," but a web of national laws and regulations, effective unions, strong EU directives, social dialogue traditions and other factors in the European labor relations context prevents them from putting their anti-union views into practice.

In the United States, these constraints are lacking or weak. U.S. labor law gives management a free hand to launch aggressive anti-union campaigns when workers try to form unions. And even when employers are found to violate the law, legal delays and weak remedies often let them get away with frustrating workers' organizing efforts.

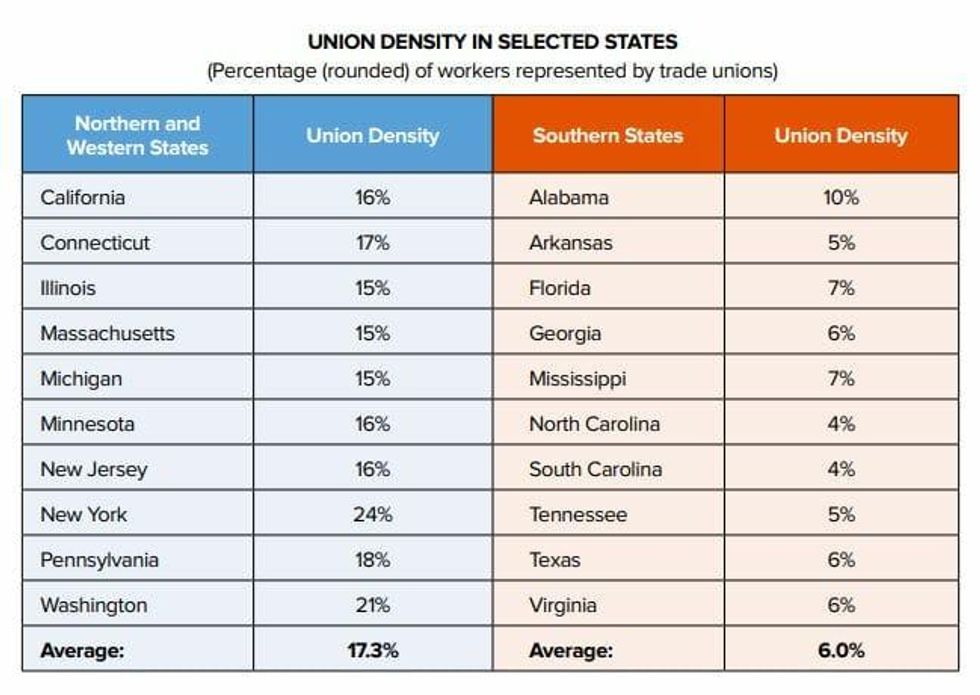

Flaws in U.S. labor law and practice are even more acute in the American South than in other regions. Some European companies appear to relish their newfound opportunities to attack trade unions in ways they cannot undertake in Europe, especially in Southern states where they have made substantial investments in recent years.

A second possible explanation for European firms' double standard is that top company leaders accept the role of trade unions and collective bargaining at home, but they wash their hands and let American managers deal with workers' organizing and the intricacies of U.S. labor law. This is a failure of due diligence for which firms should be held accountable. In either case, companies are violating international human rights and labor standards to which they have publicly committed themselves.

European companies' campaigns against workers' freedom of association in the Southern United States have wider implications and effects beyond whether employees succeed in forming trade unions. When they apply harsh anti-union strategies and tactics, European firms often argue that they simply are following advice from local business leaders and elected officials to adapt to the corporate customs and culture of the American South -- a "When in Rome, do as the Romans" ethos. But in so doing, they also are reinforcing and validating a dominant economic, social and political model that has locked the South into the bottom tier among American states under every measure of people's well-being--living standards, employment security, health, education, environmental protection, democratic participation and more.

European firms' respecting workers' freedom of association could be a driving force for far-reaching change in the American South. It could demonstrate to Southern workers that job growth, economic development and unions are not part of a zero-sum game, as they often are portrayed, but have a symbiotic relationship. Making workforce development and high-road labor policies the rule, rather than the exception, can break the historical cycle of low wages, low labor standards, low social standards and other stains on the South.

European workers and trade unions have a stake in the American South, too. Southern state government officials stress low wages, low taxes and low levels of union representation in their appeals to Europe-based multinational firms to invest in the South. This creates a temptation to relocate jobs to the U.S. South to escape European social standards.

A longer-range interest comes into play, too. As European companies become accustomed to Southern U.S.-style anti-unionism, the temptation grows to apply the same blanket strategies and tactics in Southern and Eastern Europe, or even in the heart of the European Union. Such a turn by European firms would make it even easier for U.S.-based companies in Europe to export American management-style violations of workers' organizing and collective bargaining rights.

Workers' and trade unions' interests in Europe and the United States also converge in negotiations now taking place for a trans-Atlantic trade and investment pact, sometimes called TTIP. The United States likely will pressure Europe to accept a trade arrangement promoting weak labor laws, anti-unionism, decentralized collective bargaining, low wages, low taxes, privatization, deregulation of health and environmental rules, reduced public services and other features of the U.S. model that are most prominent in the American South.

Unless they are held accountable for their conduct and rectify their behavior, European companies might tell their governments "we like the U.S. system and the way we have profited from these policies, especially in the American South." European and American workers and their allies must mobilize now to prevent American Southern-style labor practices from taking root in Europe.