Granny Hazel taught me how to feed the chickens. Hold the ear of dried corn in both hands and twist to pry the kernels from the cob, then throw it out into the yard for the waiting chickens to eat. I loved watching them peck away at the ground, eating the corn our family had grown that summer. At 5 years old, I'm sure I thought the chickens were her pets. Maybe I thought she just fed them like that because she liked to watch them peck at the ground, too, softly clucking as they did so.

It wasn't until years later that I learned she killed those chickens by twisting their necks with her bare hands to feed her family. This gentle, kind woman did what she had to do, just like countless Appalachian women before, during, and after her time.

Granny Hazel was a complex, fully realized person, as are all Appalachian people. But, because of the images propagated about the region by media and Hollywood, most only know Appalachia as one thing. Either the kind granny teaching her granddaughter to feed the chickens, or the necessary violence that is killing your own animals to eat them.

Stories about Appalachia, who tells them and who gets to claim them, matter a great deal when it comes to understanding the place and people more fully. And that understanding is critical, because without a deeper and more complete understanding of Appalachia, it will be hard for its people to build a brighter future that crosses lines of division and works toward parity between race and class.

Appalachia has been portrayed in various oversimplified and negative ways throughout modern history. Scholars such as Meredith McCarroll point out that the common stereotypical images of the region that most people know today came from the War on Poverty era of the mid-1960s. The images were voraciously mined by media makers shortly after President Lyndon Johnson stood on Tom Fletcher's porch in Martin County, Kentucky, to declare his administration would fight tirelessly to end American poverty.

These images--of an all-white populace, depressed-looking men hunched over from years working in the mines, dirty-faced and barefoot children, and women in shift dresses, holding a baby in one arm, cooking over a wood stove with the other--have defined Appalachia for at least two generations. In her new book, Unwhite: Appalachia, Race and Film (University of Georgia Press, 2018), McCarroll tells us these images are buttressed by generations of images that came before: the lazy, shiftless, oftentimes violent hillbilly man and his over-sexualized wife with their many underfed children. That these images have now shifted to be more about the out-of-work but noble coal miner, is nothing new; this trend of "rediscovering" Appalachia happens every 20-30 years, right about when the nation needs an explanation for some kind of major shift in economy or politics. But what McCarroll asks us to do is to dig a little deeper and ask why these images are the ones being taken out of the hills in the first place.

The answer, of course, has everything to do with power. McCarroll suggests we adopt the term "unwhite" to describe Appalachian people, since they are portrayed by Hollywood as neither of the dominant White culture nor of the minority cultures of people of color--they are in between, but always othered with a purpose. At the turn of the 20th century, the coal industry wanted to extract as much coal and wealth from the mountains as they possibly could. So, they worked with local politicians and national media makers to cast mountain people as either backward, ignorant, and dangerous, or as simple-minded folk in need of a strong hand. Either way, the narratives were meant to set Appalachian people squarely outside the dominant culture--a relic of the past that, if they could not help themselves out of poverty and assimilate into the dominant culture, could not be saved no matter what the country did to help. When a place and its people are cast as lesser, it makes it a whole lot easier to justify taking everything from them.

"One of the most effective means of controlling a people is controlling their image," McCarroll writes. The stories being told about Appalachians were not made or controlled by them. They had little say in what images the rest of the country saw, and how those images would shape policy, grantmaking and the local economy for generations.

What they did have control over, though, was fighting back. The powerful might have had a vested interest in keeping the people in check and the nation in the dark through the black and white images they sent out through TV and newspapers, but what they never really anticipated was that Appalachian people then and now have a vested interest in their place, their families, and their communities. And they never would have anticipated that it would be the women leading the charge.

From Paint and Cabin Creeks in West Virginia to Brookside in Harlan County, women have been on the frontlines of every labor struggle the mountains have known. Jessica Wilkerson, in To Live Here, You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice (University of Illinois Press, 2018) shows how women cared for their children and their male relatives who were disabled in the mines, or they stood on the picket lines when the men weren't allowed to. They started clinics when they were needed, like the Mud Creek Clinic, launched in 1973 by Eula Hall in Grethel, Kentucky. They organized across racial lines, like Edith and Sue Ella Easterling did at the Marrowbone Folk School; they held the line, like Betty Eldridge did when miners went on strike at the Brookside mine; they even went to work in the mines in the 1970s and '80s as a way to seek equality in the workplace.

Women, people of color, young people, and queer people have held this place together, and held it up, making sure we kept our eyes on the importance of working together to address the challenges we face, as Wilkerson points out through the story of Appalachian women activists. And yet, their names will rarely, if ever, be seen in print, on TV, or in the movies. Children will not learn about their efforts in school. It's a whole lot easier to keep Appalachia in an easily digestible box than it is to make the story more complex, and in so doing, more real.

To this day, Appalachia is a largely misunderstood place and people. National reporters have flocked to the region since 2014, the 50th Anniversary of the War on Poverty, and again in a wave of fervor after the 2016 presidential election, to seek an explanation for the nation's ills by trying to define us and tell us who we are. As McCarroll says, Appalachia has largely been cast "as a scapegoat for America's neglect, poverty, obesity, greed, and environmental destruction." For the most part, these waves of reporters have sought the easy answers--the bootstraps and hardhats narrative; the hopelessness narrative; the brain-drain narrative. And the region has suffered for their unwillingness to seek the answers to why the conditions the region faces exist at all.

No one narrative can tell the full story of an entire region and the people that live there because no one person or story can lay complete claim to a place. Appalachia, like every other region of this country, contains multitudes, and without fully grasping that and showcasing that whenever possible, not only will people outside the region never fully see us as human, but we will lose the ability to see ourselves and our complex lives within those stories. A diverse and complicated populace can never fully know who it is if every story ever told about it is missing entire plot points.

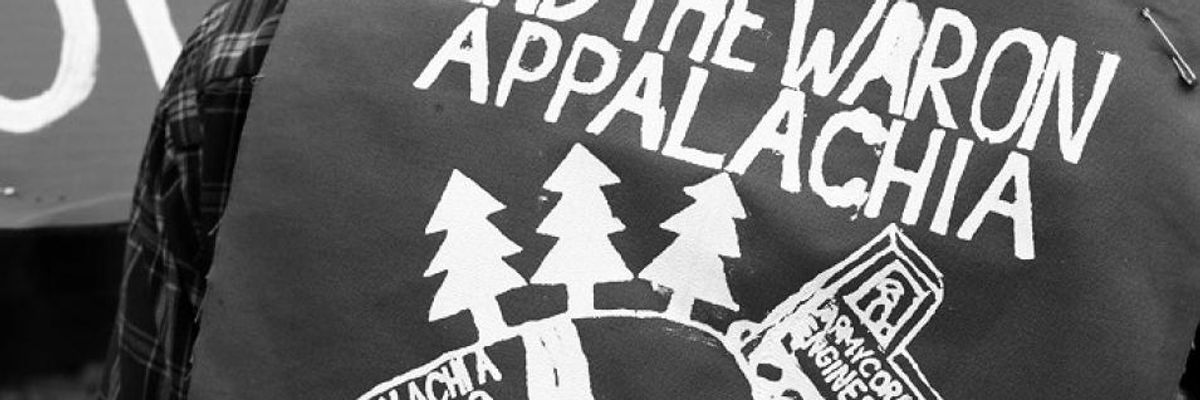

Many powerful people have worked for decades to obscure the truth about Appalachia in the hopes that they would then be able to reap as much reward for themselves as possible, completely unfettered. Throughout the history of the region, other people have always been trying to tell us who we are. In Never Justice, Never Peace: Mother Jones and the Miner Rebellion at Paint and Cabin Creeks (West Virginia University Press, 2018), Lon Kelly Savage and Ginny Savage Ayers relate how that's shaped perceptions of Mary "Mother" Jones as she witnessed and spurred on the mine wars in early 20th century West Virginia. But that theme carried forward in time to the antipoverty and welfare rights movements and union battles of the 1960s, '70s and '80s that saw women in eastern Kentucky taking lead roles, to the "War on Coal" rhetoric of today.

Now, though, as coal reserves continue to dwindle and companies like Blackjewel in Harlan County try to shutter operations without paying their workers, as governments in Kentucky and West Virginia try to strip teachers of their pay and dignity, as healthcare access for the most in need among us is once again threatened, we are remembering our history of fighting for each other, and we are standing on the line once more, just as we've always done, because this, too, is who we are.

The time has come, then, to tell a new story of this place--to reclaim the truth and the complexity of being of and from Appalachia. We must talk about the struggle and the tragedy, but we must tell the truth of those struggles and why they exist in the first place. We must tell the tales of the women who've infused an ethos of caregiving into the activism in which they felt compelled to participate, an ethos, as Wilkerson points out, that remains in the justice movements in the region today. We must fight back against the stereotypical images about Appalachia that still portray it as "the strange and peculiar place that is easy to forget," as McCarroll writes; we can't let those images define us. And, we need to know that the union organizing Mother Jones bolstered in Paint Creek was part of a larger movement for justice against oppressive systems that continues today. We must embrace the contradictions and live within them, and present to the world and to ourselves our truest form. We must understand that while we fed the chickens, we were preparing to kill them for food.

Unless we know the truth of Appalachia in our bones, we won't fully be able to build a more just and equitable future in this place because we won't even know where to start. A more complex story of self could help us take that first step, and the more truth we reveal and uncover, the more steps we'll be able to take. And just like Mother Jones, the Appalachian women activists of the mid-20th century, and the documentarians attempting to tell more honest stories of the region, we'll move forward, together, building a stronger Appalachia as we go along.