SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

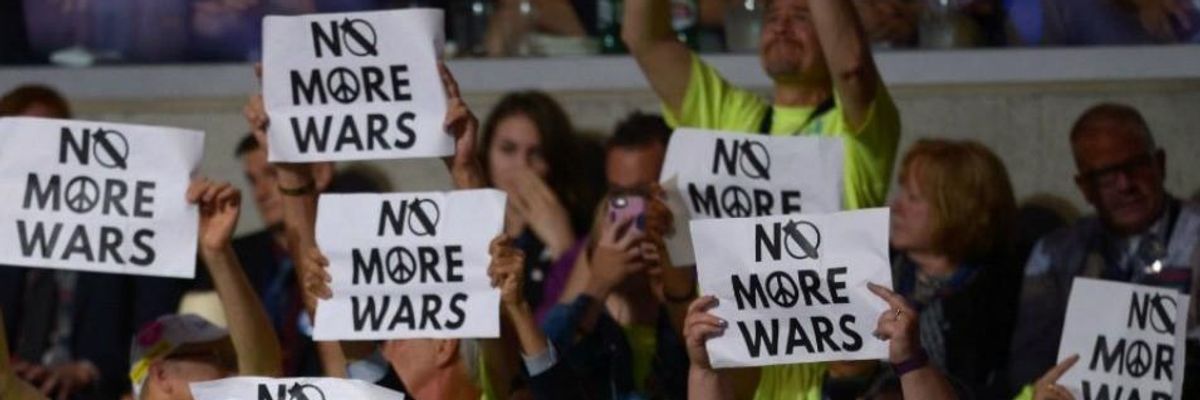

The students walked away from the unit with a deeper sense of the wars America has been and a more nuanced understanding of World War II and Vietnam. (Photo: via EuroYankee)

"I don't know...I mean I want to be one of those people...you know who do things, who create change I guess...this was inspiring...it made me want to create change...but I guess I don't know how." Three students and I were sitting in a small room gathered near a round table in the corner of the social studies office. The students had just completed a three-week instructional unit focused on two essential questions: What is a just war? How do we end war? Their teacher and I had co-created the unit both interested in whether focusing on critique of and resistance to war would bulster students' sense of agency, help them develop a more critical perspective of war and help students understand that war can be stopped by active and engaged citizens. By the end of the unit, the students weren't so sure.

"I'm always surprised by how schools in America teach. I mean there's wars all around us and the teachers here act like they don't exist and then don't directly teach the wars they do teach." The other students in the discussion agreed. "Yeah, it's like they teach that war is bad...but we already know that...we never teach in depth. I mean I know 1939 and Eisenhower and all that...I got an A but I feel like I know it skin deep. We never really talk about anything." Another student agreed providing an example of when they did go in depth. "When we studied the Atomic Bombs being dropped on Japan we had a two-day seminar examining documents but it wasn't really anything different from what was in our textbooks. I mean we all know that atomic bombs are bad, but didn't anyone speak out against them besides like Einstein? I didn't know there was like an anti-war movement for like always until this unit."

The shootings at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School and the activism that followed had already happened. A number of students at Stephens High School where I was conducting the study and co-teaching the unit had participated in a student organized walk out and a smaller number had participated in the 17 minute national walk out event where students were to read the names of 17 victims of the Stoneman Douglas shooting in silence. Like most schools, Stephens High School honored the 17 minute walk out allowing students to choose to participate, teachers if it was their free period or their entire class attended. Fearing violence, the Stephens students attended the event with a fairly heavy security presence. Students had mixed reactions. "Oh you mean the assembly?" a student responded when I asked her if she had attended. "You mean the forced social action?" another commented. Student views on both social actions (the student organized and the school organized) greatly from needed events to disorganized (the student event) to forced (the school event).

I had assumed that the activism displayed by Emma Gonzalez, David Hogg, and the other student activists who emerged from the Douglas shooting would have shown the Stephens students the way. Though the shooting and the activism played heavily in media for months afterwards and though we were intentionally teaching with activist stance, no students connected what we taught to the Stoneman activists until I raised them in class discussion. Many teachers I spoke with around the state of North Carolina shared disappointing student responses. One teacher, a participant in a larger study I have been conducting on the teaching of war taught a short unit on civil disobedience, dissent and activism in the days before the Stoneman Douglas 17 minute. Hoping to attend the rally himself (he could only go if all of his students went) was aghast when only three of his students chose to "walk out" for the official school sanction. When he asked why students didn't go he was greeted with the mundane, "It's only 17 minutes," the critical, "It's not going to do anything," to the most often given, "I don't want to miss the lecture...what's the topic...civil disobedience right?" The raised national presence of student activism against gun violence seemed to have done nothing to inspire these students I thought at the time. What I interpreted as resistance or apathy to the Stoneman-Douglas students was actually an overwhelming sense of the hugeness of the problem (of ending war) and having no idea where to begin. For even in our instructional unit focused on those who resisted war historically, the students were introduced to the people, movements, and philosophies but not what the specific steps were to actually resist, to actually cause change.

The instructional unit began by asking students "What is a just war?" We specified it, asking students to explain what they would be willing to go to war for themselves, their friends and their family. In other words, it wouldn't be someone else, it would be them doing the fighting, the struggling, the wounding and the dying. The students had nuanced answers that ran the range you might think high school students would surface. Student responses included: "if we are attacked," "if its our national interest," "if an ally is attacked...and we have a treaty with them," to "if there's like a group being murdered you know like the Holocaust," to "no wars are ever just." The students were articulate and passionate about their positions and points of view, expressing them well. They were smooth in their delivery and students able to use some historic fact as supportive example, but only some. The students used historic events as blunt instruments unable to get specific or go beyond "The Japanese attacked us!" or "The Holocaust." The students seemed to gravitate mostly to World War II for their historical example that justified war, and students who stood in opposition of war or were critical of it, struggled. World War II was as one student offered, "the good war."

The unit went on to examine how each war that America has been involved in began from the American Revolution through the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Students were shocked by the reasons in evidence. "I mean come on...they knew where the boundary was when they sent Taylor across the river" one student exclaimed. "Really Admiral Stockwell who was in a plane over the Gulf of Tonkin doesn't think an American ship was attacked?" one student asked in a hushed tone. The realizations didn't lead to change minds. "Well we're Americans look what we did with the land (taken from Mexico)" and "Vietnam was communist we didn't need to be attacked to go to war with them." We examined World War II and the Vietnam War as case studies comparing how the wars began, how they were fought and the resistance to them. Students had a very generalized sense of the anti-war movement during Vietnam, "like hippies and stuff right?" but were surprised by the resistance during World War II. They were even more surprised to learn that there was a long history of resistance to war in both the United States and other countries. Students were moved by the stories of the activists, the documents we read about their actions, Jeanette Rankin voting against war prior to both World War I and World War II, of the marches, speeches, boycotts, and other organized actions and shocked by the number of women involved, "there were so many women" one female student said in awe.

The students walked away from the unit with a deeper sense of the wars America has been and a more nuanced understanding of World War II and Vietnam. The students also understood that there was a history of anti-war activism and gained general ways that the activists engaged in them. They still, however, fell overwhelmed and lost. "It's (war) just so overwhelming...so big...I mean where do I begin" one student articulated during the interview. "I think for this (student activism) to work, more classes need to be like this one...and it can't just be for what two and a half weeks" another student shared. "In civics we learn all about the checks and balances, how a bill becomes a law, that citizens have voice...but we never learn how to organize for or like create change. We are told we have a voice but I never taught how to use it," another student shared. Another student countered that though arguing, "This was hard...it was only two and a half weeks? I mean it felt like more. That was serious stuff we studied...I don't know if I...I don't know if students can take this in more classes.

Since the events of September 11, 2001 the United States has been in a nearly constant state of war. Students need to be taught a more nuanced and complete narrative on the wars that America has been involved in. Perhaps more needed is a shift in how we teach civics, government and citizenship. In regards to both war and citizenship rather than a recitation of people, places, events, and activities that involve critical thinking, we need to help our students learn to use their voices, their writing, their research, and their activism in real spaces engaging real events. If this form of citizenship doesn't become a habit our wars will continue without a real sense of why or when or how they should be stopped.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

"I don't know...I mean I want to be one of those people...you know who do things, who create change I guess...this was inspiring...it made me want to create change...but I guess I don't know how." Three students and I were sitting in a small room gathered near a round table in the corner of the social studies office. The students had just completed a three-week instructional unit focused on two essential questions: What is a just war? How do we end war? Their teacher and I had co-created the unit both interested in whether focusing on critique of and resistance to war would bulster students' sense of agency, help them develop a more critical perspective of war and help students understand that war can be stopped by active and engaged citizens. By the end of the unit, the students weren't so sure.

"I'm always surprised by how schools in America teach. I mean there's wars all around us and the teachers here act like they don't exist and then don't directly teach the wars they do teach." The other students in the discussion agreed. "Yeah, it's like they teach that war is bad...but we already know that...we never teach in depth. I mean I know 1939 and Eisenhower and all that...I got an A but I feel like I know it skin deep. We never really talk about anything." Another student agreed providing an example of when they did go in depth. "When we studied the Atomic Bombs being dropped on Japan we had a two-day seminar examining documents but it wasn't really anything different from what was in our textbooks. I mean we all know that atomic bombs are bad, but didn't anyone speak out against them besides like Einstein? I didn't know there was like an anti-war movement for like always until this unit."

The shootings at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School and the activism that followed had already happened. A number of students at Stephens High School where I was conducting the study and co-teaching the unit had participated in a student organized walk out and a smaller number had participated in the 17 minute national walk out event where students were to read the names of 17 victims of the Stoneman Douglas shooting in silence. Like most schools, Stephens High School honored the 17 minute walk out allowing students to choose to participate, teachers if it was their free period or their entire class attended. Fearing violence, the Stephens students attended the event with a fairly heavy security presence. Students had mixed reactions. "Oh you mean the assembly?" a student responded when I asked her if she had attended. "You mean the forced social action?" another commented. Student views on both social actions (the student organized and the school organized) greatly from needed events to disorganized (the student event) to forced (the school event).

I had assumed that the activism displayed by Emma Gonzalez, David Hogg, and the other student activists who emerged from the Douglas shooting would have shown the Stephens students the way. Though the shooting and the activism played heavily in media for months afterwards and though we were intentionally teaching with activist stance, no students connected what we taught to the Stoneman activists until I raised them in class discussion. Many teachers I spoke with around the state of North Carolina shared disappointing student responses. One teacher, a participant in a larger study I have been conducting on the teaching of war taught a short unit on civil disobedience, dissent and activism in the days before the Stoneman Douglas 17 minute. Hoping to attend the rally himself (he could only go if all of his students went) was aghast when only three of his students chose to "walk out" for the official school sanction. When he asked why students didn't go he was greeted with the mundane, "It's only 17 minutes," the critical, "It's not going to do anything," to the most often given, "I don't want to miss the lecture...what's the topic...civil disobedience right?" The raised national presence of student activism against gun violence seemed to have done nothing to inspire these students I thought at the time. What I interpreted as resistance or apathy to the Stoneman-Douglas students was actually an overwhelming sense of the hugeness of the problem (of ending war) and having no idea where to begin. For even in our instructional unit focused on those who resisted war historically, the students were introduced to the people, movements, and philosophies but not what the specific steps were to actually resist, to actually cause change.

The instructional unit began by asking students "What is a just war?" We specified it, asking students to explain what they would be willing to go to war for themselves, their friends and their family. In other words, it wouldn't be someone else, it would be them doing the fighting, the struggling, the wounding and the dying. The students had nuanced answers that ran the range you might think high school students would surface. Student responses included: "if we are attacked," "if its our national interest," "if an ally is attacked...and we have a treaty with them," to "if there's like a group being murdered you know like the Holocaust," to "no wars are ever just." The students were articulate and passionate about their positions and points of view, expressing them well. They were smooth in their delivery and students able to use some historic fact as supportive example, but only some. The students used historic events as blunt instruments unable to get specific or go beyond "The Japanese attacked us!" or "The Holocaust." The students seemed to gravitate mostly to World War II for their historical example that justified war, and students who stood in opposition of war or were critical of it, struggled. World War II was as one student offered, "the good war."

The unit went on to examine how each war that America has been involved in began from the American Revolution through the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Students were shocked by the reasons in evidence. "I mean come on...they knew where the boundary was when they sent Taylor across the river" one student exclaimed. "Really Admiral Stockwell who was in a plane over the Gulf of Tonkin doesn't think an American ship was attacked?" one student asked in a hushed tone. The realizations didn't lead to change minds. "Well we're Americans look what we did with the land (taken from Mexico)" and "Vietnam was communist we didn't need to be attacked to go to war with them." We examined World War II and the Vietnam War as case studies comparing how the wars began, how they were fought and the resistance to them. Students had a very generalized sense of the anti-war movement during Vietnam, "like hippies and stuff right?" but were surprised by the resistance during World War II. They were even more surprised to learn that there was a long history of resistance to war in both the United States and other countries. Students were moved by the stories of the activists, the documents we read about their actions, Jeanette Rankin voting against war prior to both World War I and World War II, of the marches, speeches, boycotts, and other organized actions and shocked by the number of women involved, "there were so many women" one female student said in awe.

The students walked away from the unit with a deeper sense of the wars America has been and a more nuanced understanding of World War II and Vietnam. The students also understood that there was a history of anti-war activism and gained general ways that the activists engaged in them. They still, however, fell overwhelmed and lost. "It's (war) just so overwhelming...so big...I mean where do I begin" one student articulated during the interview. "I think for this (student activism) to work, more classes need to be like this one...and it can't just be for what two and a half weeks" another student shared. "In civics we learn all about the checks and balances, how a bill becomes a law, that citizens have voice...but we never learn how to organize for or like create change. We are told we have a voice but I never taught how to use it," another student shared. Another student countered that though arguing, "This was hard...it was only two and a half weeks? I mean it felt like more. That was serious stuff we studied...I don't know if I...I don't know if students can take this in more classes.

Since the events of September 11, 2001 the United States has been in a nearly constant state of war. Students need to be taught a more nuanced and complete narrative on the wars that America has been involved in. Perhaps more needed is a shift in how we teach civics, government and citizenship. In regards to both war and citizenship rather than a recitation of people, places, events, and activities that involve critical thinking, we need to help our students learn to use their voices, their writing, their research, and their activism in real spaces engaging real events. If this form of citizenship doesn't become a habit our wars will continue without a real sense of why or when or how they should be stopped.

"I don't know...I mean I want to be one of those people...you know who do things, who create change I guess...this was inspiring...it made me want to create change...but I guess I don't know how." Three students and I were sitting in a small room gathered near a round table in the corner of the social studies office. The students had just completed a three-week instructional unit focused on two essential questions: What is a just war? How do we end war? Their teacher and I had co-created the unit both interested in whether focusing on critique of and resistance to war would bulster students' sense of agency, help them develop a more critical perspective of war and help students understand that war can be stopped by active and engaged citizens. By the end of the unit, the students weren't so sure.

"I'm always surprised by how schools in America teach. I mean there's wars all around us and the teachers here act like they don't exist and then don't directly teach the wars they do teach." The other students in the discussion agreed. "Yeah, it's like they teach that war is bad...but we already know that...we never teach in depth. I mean I know 1939 and Eisenhower and all that...I got an A but I feel like I know it skin deep. We never really talk about anything." Another student agreed providing an example of when they did go in depth. "When we studied the Atomic Bombs being dropped on Japan we had a two-day seminar examining documents but it wasn't really anything different from what was in our textbooks. I mean we all know that atomic bombs are bad, but didn't anyone speak out against them besides like Einstein? I didn't know there was like an anti-war movement for like always until this unit."

The shootings at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School and the activism that followed had already happened. A number of students at Stephens High School where I was conducting the study and co-teaching the unit had participated in a student organized walk out and a smaller number had participated in the 17 minute national walk out event where students were to read the names of 17 victims of the Stoneman Douglas shooting in silence. Like most schools, Stephens High School honored the 17 minute walk out allowing students to choose to participate, teachers if it was their free period or their entire class attended. Fearing violence, the Stephens students attended the event with a fairly heavy security presence. Students had mixed reactions. "Oh you mean the assembly?" a student responded when I asked her if she had attended. "You mean the forced social action?" another commented. Student views on both social actions (the student organized and the school organized) greatly from needed events to disorganized (the student event) to forced (the school event).

I had assumed that the activism displayed by Emma Gonzalez, David Hogg, and the other student activists who emerged from the Douglas shooting would have shown the Stephens students the way. Though the shooting and the activism played heavily in media for months afterwards and though we were intentionally teaching with activist stance, no students connected what we taught to the Stoneman activists until I raised them in class discussion. Many teachers I spoke with around the state of North Carolina shared disappointing student responses. One teacher, a participant in a larger study I have been conducting on the teaching of war taught a short unit on civil disobedience, dissent and activism in the days before the Stoneman Douglas 17 minute. Hoping to attend the rally himself (he could only go if all of his students went) was aghast when only three of his students chose to "walk out" for the official school sanction. When he asked why students didn't go he was greeted with the mundane, "It's only 17 minutes," the critical, "It's not going to do anything," to the most often given, "I don't want to miss the lecture...what's the topic...civil disobedience right?" The raised national presence of student activism against gun violence seemed to have done nothing to inspire these students I thought at the time. What I interpreted as resistance or apathy to the Stoneman-Douglas students was actually an overwhelming sense of the hugeness of the problem (of ending war) and having no idea where to begin. For even in our instructional unit focused on those who resisted war historically, the students were introduced to the people, movements, and philosophies but not what the specific steps were to actually resist, to actually cause change.

The instructional unit began by asking students "What is a just war?" We specified it, asking students to explain what they would be willing to go to war for themselves, their friends and their family. In other words, it wouldn't be someone else, it would be them doing the fighting, the struggling, the wounding and the dying. The students had nuanced answers that ran the range you might think high school students would surface. Student responses included: "if we are attacked," "if its our national interest," "if an ally is attacked...and we have a treaty with them," to "if there's like a group being murdered you know like the Holocaust," to "no wars are ever just." The students were articulate and passionate about their positions and points of view, expressing them well. They were smooth in their delivery and students able to use some historic fact as supportive example, but only some. The students used historic events as blunt instruments unable to get specific or go beyond "The Japanese attacked us!" or "The Holocaust." The students seemed to gravitate mostly to World War II for their historical example that justified war, and students who stood in opposition of war or were critical of it, struggled. World War II was as one student offered, "the good war."

The unit went on to examine how each war that America has been involved in began from the American Revolution through the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Students were shocked by the reasons in evidence. "I mean come on...they knew where the boundary was when they sent Taylor across the river" one student exclaimed. "Really Admiral Stockwell who was in a plane over the Gulf of Tonkin doesn't think an American ship was attacked?" one student asked in a hushed tone. The realizations didn't lead to change minds. "Well we're Americans look what we did with the land (taken from Mexico)" and "Vietnam was communist we didn't need to be attacked to go to war with them." We examined World War II and the Vietnam War as case studies comparing how the wars began, how they were fought and the resistance to them. Students had a very generalized sense of the anti-war movement during Vietnam, "like hippies and stuff right?" but were surprised by the resistance during World War II. They were even more surprised to learn that there was a long history of resistance to war in both the United States and other countries. Students were moved by the stories of the activists, the documents we read about their actions, Jeanette Rankin voting against war prior to both World War I and World War II, of the marches, speeches, boycotts, and other organized actions and shocked by the number of women involved, "there were so many women" one female student said in awe.

The students walked away from the unit with a deeper sense of the wars America has been and a more nuanced understanding of World War II and Vietnam. The students also understood that there was a history of anti-war activism and gained general ways that the activists engaged in them. They still, however, fell overwhelmed and lost. "It's (war) just so overwhelming...so big...I mean where do I begin" one student articulated during the interview. "I think for this (student activism) to work, more classes need to be like this one...and it can't just be for what two and a half weeks" another student shared. "In civics we learn all about the checks and balances, how a bill becomes a law, that citizens have voice...but we never learn how to organize for or like create change. We are told we have a voice but I never taught how to use it," another student shared. Another student countered that though arguing, "This was hard...it was only two and a half weeks? I mean it felt like more. That was serious stuff we studied...I don't know if I...I don't know if students can take this in more classes.

Since the events of September 11, 2001 the United States has been in a nearly constant state of war. Students need to be taught a more nuanced and complete narrative on the wars that America has been involved in. Perhaps more needed is a shift in how we teach civics, government and citizenship. In regards to both war and citizenship rather than a recitation of people, places, events, and activities that involve critical thinking, we need to help our students learn to use their voices, their writing, their research, and their activism in real spaces engaging real events. If this form of citizenship doesn't become a habit our wars will continue without a real sense of why or when or how they should be stopped.