SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

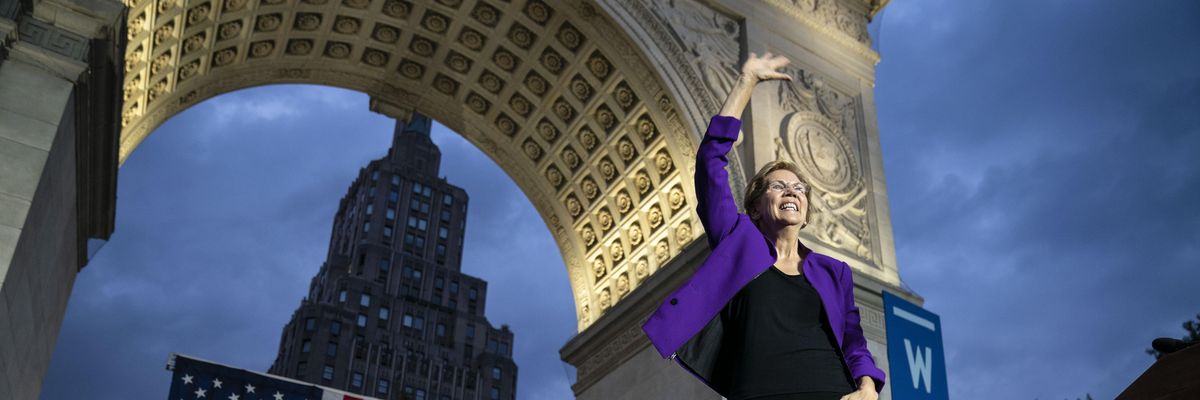

2020 Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) arrives for a rally in Washington Square Park on September 16, 2019 in New York City. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Capitalism dumps its financial dead in corporate bankruptcy court--and Elizabeth Warren knows where the bodies are buried.

Over thirty years ago, Warren made it her academic mission to understand the intricacies of how companies die, how the law decides who inherits the assets of the corpse--and how that increases inequality in the economy.

While there is a trope that Warren was a late convert to progressivism--itself a bit debunked since she voted against Reagan in 1980--if you really want to place Warren on the political spectrum, Warren's core radicalism is reflected in the critique of corporate bankruptcy she made over 30 years ago where she highlighted how government, not some objective "market", decides who wins and who loses in the way bankruptcy rules shape our broader economic system.

One divide between liberalism and radicalism is whether politicians let the market shape inequality in the economy and then use tax and spending policies to clean up the mess afterwards, the paradigmatic liberal approach. This contrasts with radicals who believe in shaping the rules of the economy up front to prevent inequality expanding in the first place.

Warren's writings and her stump speech advocacy for "big structural change" place her decidedly in the second camp, reflected in her policy proposals--from remaking the financial system to calling for putting workers on boards of directors to promoting breaking up monopolies to reshaping housing markets to arguing for redistributing wealth itself through a wealth tax.

Over thirty years ago, Warren was arguing economic redistribution should not be left to budget politics but that policymakers need to be "dealing with the distributive issues that bankruptcy policy implicates" that create unequal wealth in the first place.

Your eyes may glaze-over hearing the words "corporate bankruptcy"--and that's the point. The media tells endless stories of the winners of capitalist competition--the Apples, the Googles, the Exxons--but most firms, especially smaller firms that are never listed on the stock market, DON'T survive so the distribution of their assets in bankruptcy court matters. But that process is arcane and meant to be that way to the advantage of those who benefit from it.

"You see Warren's radical thinking most clearly in her writing on corporate bankruptcy."

Donald Trump epitomizes this reality since multiple firms he has owned have gone through bankruptcy, stiffing creditors and contractors, even as Trump himself leveraged the legal system to shield most of his own personal assets. As Trump himself said when asked about his bankruptcies, "I've taken advantage of the laws of this country."

Documenting how the wealthy like Trump take advantage of the bankruptcy laws to increase economic inequality and how to design the law to promote greater equity has been much of Warren's life work.

Much of the media focus on Elizabeth Warren's political history has justifiably been on her crusade to defend individual debtors from punitive bankruptcy legislation, but you see Warren's radical thinking most clearly in her writing on corporate bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy is actually at the center of our economy, as Warren wrote back in 1992, "The most difficult social problems get dumped into bankruptcy--mass torts, environmental disasters, the dashed expectations of retired employees." The failures of capitalism have to be managed by bankruptcy court judges, as kids in chemotherapy, union workers with empty pensions and bankers square off to divvy up the assets of a belly-up chemical company that poisoned groundwater for multiple communities.

Economists and legal writers like to pretend that the economy is made up just of markets and contracts, but that is a "fiction" according to Warren that lasts only until one party or the other no longer has the money to make good on those promises. At that point, judges in bankruptcy court apply all the "normative issues of fairness ignored in contract law" that Warren argues the business class pretends has no place in economic thinking.

Bankruptcy exists not to further markets but to correct the mistakes that led to bankruptcy happening in the first place--and brings active government concerns for distributional fairness into play. "It provides a forum for negotiating deals, and, ultimately, it allocates the value of a firm to all claimants, making difficult distributional decisions among competing parties."

The dirty secret of corporate law in the U.S. is that corporations are created under state law, not federal law, which leads to a "race to the bottom" as states compete to make their local laws more corporate friendly. Federal bankruptcy is one of the "few aspects of commercial life...addressed in the Constitution," wrote Warren and it overrides some of the worst aspects of state corporate law.

"At the heart of Warren's ideological vision is a clear demand that the market and property rights be subordinate to the human needs and democratic will of the community."

While Warren has sharp criticisms of the federal bankruptcy code, it would be even worse if parties had to "battle for assets under the state law scheme" where banks and other sophisticated creditors would largely be the only ones able to scavenge the carcass of a defunct firm. State law generally gives enhanced collection rights to certain favored creditors: "involuntary creditors, such as tort victims and environmental cleanup funds...would likely come into the claims process only after others had taken the most valuable assets."

The key thing federal bankruptcy law can do that state laws don't is ideally ensure everyone who has potential claims on the assets of the firm get a place at the table when assets of the firm are divided up. Pension holders owed money long into the future get into the same court proceeding with the banks holding immediate debt, "both present and future claims at once" as Warren highlights. With this focus, there is stronger legal emphasis on keeping a firm going as the most effective way to generate ongoing revenue for unpaid obligations. Instead of "inefficient" and "nonproductive strategic behavior" under state debt collection, bankruptcy law is a "collective-action system...to achieve significant cost savings," emphasizing where Warren sees efficiency gains from collective government action over individual market transactions.

While Warren thinks federal bankruptcy law is far superior to dog-eat-dog state asset collection systems, she highlights the way every legal rule in bankruptcy reverberates in the broader economy to shape market decisions, sometimes to the good, more often to the advantage of the wealthy, but never in some "natural" outcome as conservative economic thinkers would have it.

Warren flatly writes: "Any legal rule will cause some redistribution of wealth."

This may be obvious to many progressives, but it challenges the core capitalist legal ideology that law can stand outside the market and be a neutral arbiter of contractual relationships. Instead, Warren sees legal rules as inherently favoring one group over another at every economic point of negotiation: "A rule of ownership, a rule of liability, or a rule of priority will relatively advantage or disadvantage competing parties."

Legal rules are therefore inherently normative, or as Warren wryly observes, "It is not a difference in economic circumstances that dictates that a director of a bankrupt French company is more likely to go to jail than his American counterpart."

Conservative thinkers generally want bankruptcy to focus solely on the "preservation of value for public shareholders and bondholders" but Warren notes that, to its credit, Congress has clearly made redistributional goals to other parties part of the focus of bankruptcy proceedings:

"Virtually every substantive amendment to the Bankruptcy Code since its passage in 1978 has specifically addressed redistributional concerns. The Code is thus designed not only to enhance the value of the failing business, but also to distribute that value among interested parties in specified ways."

Before 1978, the Securities and Exchange Commission had a direct role in overseeing most bankruptcies and that role was largely removed in the law passed that year, argues Warren, precisely because the SEC was seen as too much favoring investors over other stakeholders.

Not that those with economic power regularly lose out in federal bankruptcy court; far from it as Warren repeatedly details in her work. In fact, stakeholders with explicit debt-based contracts with a firm, so-called "secured creditors", consistently get priority by bankruptcy judges, directing resources away from tort victims or others with more diffuse claims. Even where "creditors collectively might be better off with the business as a going concern," Warren writes, "secured creditors can nonetheless insist on liquidation, unless they receive their statutorily protected treatment."

She does detail a few hard-fought for legislative successes against the secured creditors, notably on behalf of workers in bankrupt firms. Statutes have been enacted to give employees owed past due wages priority in bankruptcy court and the law has favored reorganization of firms over liquidation in order to "permit employees to keep their jobs."

Still, despite those exceptions, secured creditors under what are called "full priority rules" win out in most bankruptcy fights because, as Warren argues, they helped write most of the rules. "The group that profits from priority is well-funded and active, fully represented in all the policy debates and in the decision-making bodies. Their representatives are present at every drafting committee meeting and debate on the subject."

At the other end of the spectrum are consumer debtors who "have a perpetual problem" in Warren's words: "they do not have money and they do not organize." Formal consumer groups like the National Consumer Law Center and Consumer Federation of America are "underfunded" and spread over too many issues to compete against the well-financing focus of the financial industry in crafting bankruptcy laws. Grassroots groups with higher degrees of organization like labor and civil rights groups have more of a voice in bankruptcy policy-making but "compared with issues, such as union dues check-offs and affirmative action, bankruptcy was never a top priority," so, as Warren argued, the monied interests with their singular focus and far deeper pockets dominate the process far more of the time.

Warren's diagnosis of the problem of inequality dating back thirty years in her writing is remarkably the same as what she says on the campaign trail now: the solution is not just getting better technocrats running the system but reducing the power of financial interests and increasing the voice and organizing power of average workers and consumers to control what laws get written in the first place.

Warren focuses relentlessly in her work on the role of firms not just as profit-maximizing machines for shareholders--the conservative ideal--but as institutions serving the broader economy, the perpetual focus of progressives promoting industrial planning.

Industrial planning is usually talked about on the left only after firms have shut down in a community--but Warren focuses on bankruptcy law as bringing the broader social values of industrial planning to bear before companies disappear

One key goal in bankruptcy is keeping the firm going. Partly, this enhances the value of its assets to pay off its obligations, but it also serves broader political interests of those outside contract relationships in the market. Warren wrote:

"the revival of an otherwise failing business also serves the distributional interests of many who are not technically "creditors" but who have an interest in a business's continued existence. Older employees who could not have retrained for other jobs, customers who would have to resort to less attractive, alternative suppliers of goods and services, suppliers who would have lost current customers, nearby property owners who would have suffered declining property values, and states or municipalities that would have faced shrinking tax bases benefit from the reorganization's success."

State corporate law and general contract law studiously exclude broader community stakeholders from legal proceedings over corporate decision-making, but federal bankruptcy statutes create a real role for those interests--and Warren makes clear that expanding its focus on those broader community interests when a firm fails should be the priority.

Creditors may want to dismantle the firm to quickly get paid but bankruptcy court, Warren argues, is where government is mandated to step into to protect the values the market ignores.

Repeatedly in her writing, Warren condemns pro-liquidation legal scholars for ignoring these concerns and de facto encouraging government bailouts of those left behind, rather than holding the creditors who financed the failures financially accountable. Even where a firm may not ultimately survive as with bankruptcy proceedings involving asbestos makers like Johns-Manville, Warren details how courts required firms and their creditors to exhaust "their private resources before the government would step in with relief", giving "those who depend on the failing business a chance...to adjust to the losses they will face."

Warren's view of using bankruptcy to protect broader non-market community interests reflects her deep ideological challenge to market economics. Warren argues that markets ignores "parties without legal rights" but we need a legal system to "protect these parties [and] more than the goods that are traded by private contract." Many continuing relationships have not formalized in our economy with market contracts and to "presume either that only contract-based relationships convey value or that only the value of such relationships should be relevant to the policy goals of a legal system ignores this reality."

Warren thirty year ago was a very public combatant with conservative "law and economics" writers, allying publicly with Duncan Kenney and the Critical Legal Studies opponents of the right, equivalent to raising the Red Flag in the legal brawling of the time. As she would argue citing Kennedy in one 1993 piece "the insulation from value judgments that economic analysis offers is illusory." Traditional views of the law just obscured the political choices in the law that favored one group (usually the wealthy) over others

Warren openly mocked the idea that there was any "real" market that law was supposed to try to drive the economy towards. Any attempt to discuss policy "in a perfect market is a Zenlike exercise, much like imagining one hand clasping," so attempts to imagine a "perfect market" were "worth little." As early as 1987, Warren was trashing the economic models of law and economics with their "simple answers" where "economic analysis is utterly self-referential...within a confined, abstract scheme" with no empirical basis in reality.

Conservatives, she wrote, must assume a sufficiently imperfect market for businesses to fail, but a sufficiently perfect market for their "version of a 'market based' solution' to be effective in dealing with those failures. I have difficulty envisioning that market."

Warren's was an empirical critique of how markets function, but it was also a values-based statement that recognizing just the interests of those with property rights in the market would fundamentally be unjust. She rejected market-based bankruptcy schemes as one where those without direct contracts with a firm, including "tort victims, discrimination and harassment complainants, or antitrust plaintiffs, would be left out." A market approach "is overtly distributional in a regressive sense" in redistributing wealth away from those with weak or no property rights claims in the market.

At the heart of Warren's ideological vision is a clear demand that the market and property rights be subordinate to the human needs and democratic will of the community.

Even as the corporate Right has been determined to conquer the courts in order to shape the law to further corporate interests, the liberal movement has been remarkably unfocused on the role of law in promoting economic inequality through the rules of the market.

Liberals have tended to treat battles in the courts as the place where social issues like abortion and gay marriage battles play out, while reserving their energy fighting economic inequality for tax and budget battles. Based on her corporate bankruptcy writings and current proposals, a Warren Presidency, probably even more than a Sanders Presidency, would refocus the liberal-left on how legal rules decide winners and losers in the economy before a widget is produced or a line of code is written.

All her skepticism of markets is reflected in Warren's array of economic plans in her Presidential run which systematically subordinates every market and property rights claim to regulatory supervision. Most on point is her proposed "Accountable Capitalism Act" that would take supervision of large corporations away from the states and put them under federal regulation- and require them to "consider the interests of all corporate stakeholders--including employees, customers, shareholders, and the communities in which the company operates," exactly the broader stakeholder interests usually considered only once companies have failed and gone into bankruptcy court.

Warren may call herself a "capitalist to my bones" but it is a "capitalism" in opposition to the systematic valorization of property rights and market solutions that is currently embedded in our economic and legal system.

Warren has spent decades arguing markets are the legal creation of government rules and argues for far-reaching changes in how that government should design those rules. Whatever you call it, Warren's analysis dating back thirty years and the proposals she now promotes reflects an ideology that would make her orders of magnitude more radical than any President in our history.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Capitalism dumps its financial dead in corporate bankruptcy court--and Elizabeth Warren knows where the bodies are buried.

Over thirty years ago, Warren made it her academic mission to understand the intricacies of how companies die, how the law decides who inherits the assets of the corpse--and how that increases inequality in the economy.

While there is a trope that Warren was a late convert to progressivism--itself a bit debunked since she voted against Reagan in 1980--if you really want to place Warren on the political spectrum, Warren's core radicalism is reflected in the critique of corporate bankruptcy she made over 30 years ago where she highlighted how government, not some objective "market", decides who wins and who loses in the way bankruptcy rules shape our broader economic system.

One divide between liberalism and radicalism is whether politicians let the market shape inequality in the economy and then use tax and spending policies to clean up the mess afterwards, the paradigmatic liberal approach. This contrasts with radicals who believe in shaping the rules of the economy up front to prevent inequality expanding in the first place.

Warren's writings and her stump speech advocacy for "big structural change" place her decidedly in the second camp, reflected in her policy proposals--from remaking the financial system to calling for putting workers on boards of directors to promoting breaking up monopolies to reshaping housing markets to arguing for redistributing wealth itself through a wealth tax.

Over thirty years ago, Warren was arguing economic redistribution should not be left to budget politics but that policymakers need to be "dealing with the distributive issues that bankruptcy policy implicates" that create unequal wealth in the first place.

Your eyes may glaze-over hearing the words "corporate bankruptcy"--and that's the point. The media tells endless stories of the winners of capitalist competition--the Apples, the Googles, the Exxons--but most firms, especially smaller firms that are never listed on the stock market, DON'T survive so the distribution of their assets in bankruptcy court matters. But that process is arcane and meant to be that way to the advantage of those who benefit from it.

"You see Warren's radical thinking most clearly in her writing on corporate bankruptcy."

Donald Trump epitomizes this reality since multiple firms he has owned have gone through bankruptcy, stiffing creditors and contractors, even as Trump himself leveraged the legal system to shield most of his own personal assets. As Trump himself said when asked about his bankruptcies, "I've taken advantage of the laws of this country."

Documenting how the wealthy like Trump take advantage of the bankruptcy laws to increase economic inequality and how to design the law to promote greater equity has been much of Warren's life work.

Much of the media focus on Elizabeth Warren's political history has justifiably been on her crusade to defend individual debtors from punitive bankruptcy legislation, but you see Warren's radical thinking most clearly in her writing on corporate bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy is actually at the center of our economy, as Warren wrote back in 1992, "The most difficult social problems get dumped into bankruptcy--mass torts, environmental disasters, the dashed expectations of retired employees." The failures of capitalism have to be managed by bankruptcy court judges, as kids in chemotherapy, union workers with empty pensions and bankers square off to divvy up the assets of a belly-up chemical company that poisoned groundwater for multiple communities.

Economists and legal writers like to pretend that the economy is made up just of markets and contracts, but that is a "fiction" according to Warren that lasts only until one party or the other no longer has the money to make good on those promises. At that point, judges in bankruptcy court apply all the "normative issues of fairness ignored in contract law" that Warren argues the business class pretends has no place in economic thinking.

Bankruptcy exists not to further markets but to correct the mistakes that led to bankruptcy happening in the first place--and brings active government concerns for distributional fairness into play. "It provides a forum for negotiating deals, and, ultimately, it allocates the value of a firm to all claimants, making difficult distributional decisions among competing parties."

The dirty secret of corporate law in the U.S. is that corporations are created under state law, not federal law, which leads to a "race to the bottom" as states compete to make their local laws more corporate friendly. Federal bankruptcy is one of the "few aspects of commercial life...addressed in the Constitution," wrote Warren and it overrides some of the worst aspects of state corporate law.

"At the heart of Warren's ideological vision is a clear demand that the market and property rights be subordinate to the human needs and democratic will of the community."

While Warren has sharp criticisms of the federal bankruptcy code, it would be even worse if parties had to "battle for assets under the state law scheme" where banks and other sophisticated creditors would largely be the only ones able to scavenge the carcass of a defunct firm. State law generally gives enhanced collection rights to certain favored creditors: "involuntary creditors, such as tort victims and environmental cleanup funds...would likely come into the claims process only after others had taken the most valuable assets."

The key thing federal bankruptcy law can do that state laws don't is ideally ensure everyone who has potential claims on the assets of the firm get a place at the table when assets of the firm are divided up. Pension holders owed money long into the future get into the same court proceeding with the banks holding immediate debt, "both present and future claims at once" as Warren highlights. With this focus, there is stronger legal emphasis on keeping a firm going as the most effective way to generate ongoing revenue for unpaid obligations. Instead of "inefficient" and "nonproductive strategic behavior" under state debt collection, bankruptcy law is a "collective-action system...to achieve significant cost savings," emphasizing where Warren sees efficiency gains from collective government action over individual market transactions.

While Warren thinks federal bankruptcy law is far superior to dog-eat-dog state asset collection systems, she highlights the way every legal rule in bankruptcy reverberates in the broader economy to shape market decisions, sometimes to the good, more often to the advantage of the wealthy, but never in some "natural" outcome as conservative economic thinkers would have it.

Warren flatly writes: "Any legal rule will cause some redistribution of wealth."

This may be obvious to many progressives, but it challenges the core capitalist legal ideology that law can stand outside the market and be a neutral arbiter of contractual relationships. Instead, Warren sees legal rules as inherently favoring one group over another at every economic point of negotiation: "A rule of ownership, a rule of liability, or a rule of priority will relatively advantage or disadvantage competing parties."

Legal rules are therefore inherently normative, or as Warren wryly observes, "It is not a difference in economic circumstances that dictates that a director of a bankrupt French company is more likely to go to jail than his American counterpart."

Conservative thinkers generally want bankruptcy to focus solely on the "preservation of value for public shareholders and bondholders" but Warren notes that, to its credit, Congress has clearly made redistributional goals to other parties part of the focus of bankruptcy proceedings:

"Virtually every substantive amendment to the Bankruptcy Code since its passage in 1978 has specifically addressed redistributional concerns. The Code is thus designed not only to enhance the value of the failing business, but also to distribute that value among interested parties in specified ways."

Before 1978, the Securities and Exchange Commission had a direct role in overseeing most bankruptcies and that role was largely removed in the law passed that year, argues Warren, precisely because the SEC was seen as too much favoring investors over other stakeholders.

Not that those with economic power regularly lose out in federal bankruptcy court; far from it as Warren repeatedly details in her work. In fact, stakeholders with explicit debt-based contracts with a firm, so-called "secured creditors", consistently get priority by bankruptcy judges, directing resources away from tort victims or others with more diffuse claims. Even where "creditors collectively might be better off with the business as a going concern," Warren writes, "secured creditors can nonetheless insist on liquidation, unless they receive their statutorily protected treatment."

She does detail a few hard-fought for legislative successes against the secured creditors, notably on behalf of workers in bankrupt firms. Statutes have been enacted to give employees owed past due wages priority in bankruptcy court and the law has favored reorganization of firms over liquidation in order to "permit employees to keep their jobs."

Still, despite those exceptions, secured creditors under what are called "full priority rules" win out in most bankruptcy fights because, as Warren argues, they helped write most of the rules. "The group that profits from priority is well-funded and active, fully represented in all the policy debates and in the decision-making bodies. Their representatives are present at every drafting committee meeting and debate on the subject."

At the other end of the spectrum are consumer debtors who "have a perpetual problem" in Warren's words: "they do not have money and they do not organize." Formal consumer groups like the National Consumer Law Center and Consumer Federation of America are "underfunded" and spread over too many issues to compete against the well-financing focus of the financial industry in crafting bankruptcy laws. Grassroots groups with higher degrees of organization like labor and civil rights groups have more of a voice in bankruptcy policy-making but "compared with issues, such as union dues check-offs and affirmative action, bankruptcy was never a top priority," so, as Warren argued, the monied interests with their singular focus and far deeper pockets dominate the process far more of the time.

Warren's diagnosis of the problem of inequality dating back thirty years in her writing is remarkably the same as what she says on the campaign trail now: the solution is not just getting better technocrats running the system but reducing the power of financial interests and increasing the voice and organizing power of average workers and consumers to control what laws get written in the first place.

Warren focuses relentlessly in her work on the role of firms not just as profit-maximizing machines for shareholders--the conservative ideal--but as institutions serving the broader economy, the perpetual focus of progressives promoting industrial planning.

Industrial planning is usually talked about on the left only after firms have shut down in a community--but Warren focuses on bankruptcy law as bringing the broader social values of industrial planning to bear before companies disappear

One key goal in bankruptcy is keeping the firm going. Partly, this enhances the value of its assets to pay off its obligations, but it also serves broader political interests of those outside contract relationships in the market. Warren wrote:

"the revival of an otherwise failing business also serves the distributional interests of many who are not technically "creditors" but who have an interest in a business's continued existence. Older employees who could not have retrained for other jobs, customers who would have to resort to less attractive, alternative suppliers of goods and services, suppliers who would have lost current customers, nearby property owners who would have suffered declining property values, and states or municipalities that would have faced shrinking tax bases benefit from the reorganization's success."

State corporate law and general contract law studiously exclude broader community stakeholders from legal proceedings over corporate decision-making, but federal bankruptcy statutes create a real role for those interests--and Warren makes clear that expanding its focus on those broader community interests when a firm fails should be the priority.

Creditors may want to dismantle the firm to quickly get paid but bankruptcy court, Warren argues, is where government is mandated to step into to protect the values the market ignores.

Repeatedly in her writing, Warren condemns pro-liquidation legal scholars for ignoring these concerns and de facto encouraging government bailouts of those left behind, rather than holding the creditors who financed the failures financially accountable. Even where a firm may not ultimately survive as with bankruptcy proceedings involving asbestos makers like Johns-Manville, Warren details how courts required firms and their creditors to exhaust "their private resources before the government would step in with relief", giving "those who depend on the failing business a chance...to adjust to the losses they will face."

Warren's view of using bankruptcy to protect broader non-market community interests reflects her deep ideological challenge to market economics. Warren argues that markets ignores "parties without legal rights" but we need a legal system to "protect these parties [and] more than the goods that are traded by private contract." Many continuing relationships have not formalized in our economy with market contracts and to "presume either that only contract-based relationships convey value or that only the value of such relationships should be relevant to the policy goals of a legal system ignores this reality."

Warren thirty year ago was a very public combatant with conservative "law and economics" writers, allying publicly with Duncan Kenney and the Critical Legal Studies opponents of the right, equivalent to raising the Red Flag in the legal brawling of the time. As she would argue citing Kennedy in one 1993 piece "the insulation from value judgments that economic analysis offers is illusory." Traditional views of the law just obscured the political choices in the law that favored one group (usually the wealthy) over others

Warren openly mocked the idea that there was any "real" market that law was supposed to try to drive the economy towards. Any attempt to discuss policy "in a perfect market is a Zenlike exercise, much like imagining one hand clasping," so attempts to imagine a "perfect market" were "worth little." As early as 1987, Warren was trashing the economic models of law and economics with their "simple answers" where "economic analysis is utterly self-referential...within a confined, abstract scheme" with no empirical basis in reality.

Conservatives, she wrote, must assume a sufficiently imperfect market for businesses to fail, but a sufficiently perfect market for their "version of a 'market based' solution' to be effective in dealing with those failures. I have difficulty envisioning that market."

Warren's was an empirical critique of how markets function, but it was also a values-based statement that recognizing just the interests of those with property rights in the market would fundamentally be unjust. She rejected market-based bankruptcy schemes as one where those without direct contracts with a firm, including "tort victims, discrimination and harassment complainants, or antitrust plaintiffs, would be left out." A market approach "is overtly distributional in a regressive sense" in redistributing wealth away from those with weak or no property rights claims in the market.

At the heart of Warren's ideological vision is a clear demand that the market and property rights be subordinate to the human needs and democratic will of the community.

Even as the corporate Right has been determined to conquer the courts in order to shape the law to further corporate interests, the liberal movement has been remarkably unfocused on the role of law in promoting economic inequality through the rules of the market.

Liberals have tended to treat battles in the courts as the place where social issues like abortion and gay marriage battles play out, while reserving their energy fighting economic inequality for tax and budget battles. Based on her corporate bankruptcy writings and current proposals, a Warren Presidency, probably even more than a Sanders Presidency, would refocus the liberal-left on how legal rules decide winners and losers in the economy before a widget is produced or a line of code is written.

All her skepticism of markets is reflected in Warren's array of economic plans in her Presidential run which systematically subordinates every market and property rights claim to regulatory supervision. Most on point is her proposed "Accountable Capitalism Act" that would take supervision of large corporations away from the states and put them under federal regulation- and require them to "consider the interests of all corporate stakeholders--including employees, customers, shareholders, and the communities in which the company operates," exactly the broader stakeholder interests usually considered only once companies have failed and gone into bankruptcy court.

Warren may call herself a "capitalist to my bones" but it is a "capitalism" in opposition to the systematic valorization of property rights and market solutions that is currently embedded in our economic and legal system.

Warren has spent decades arguing markets are the legal creation of government rules and argues for far-reaching changes in how that government should design those rules. Whatever you call it, Warren's analysis dating back thirty years and the proposals she now promotes reflects an ideology that would make her orders of magnitude more radical than any President in our history.

Capitalism dumps its financial dead in corporate bankruptcy court--and Elizabeth Warren knows where the bodies are buried.

Over thirty years ago, Warren made it her academic mission to understand the intricacies of how companies die, how the law decides who inherits the assets of the corpse--and how that increases inequality in the economy.

While there is a trope that Warren was a late convert to progressivism--itself a bit debunked since she voted against Reagan in 1980--if you really want to place Warren on the political spectrum, Warren's core radicalism is reflected in the critique of corporate bankruptcy she made over 30 years ago where she highlighted how government, not some objective "market", decides who wins and who loses in the way bankruptcy rules shape our broader economic system.

One divide between liberalism and radicalism is whether politicians let the market shape inequality in the economy and then use tax and spending policies to clean up the mess afterwards, the paradigmatic liberal approach. This contrasts with radicals who believe in shaping the rules of the economy up front to prevent inequality expanding in the first place.

Warren's writings and her stump speech advocacy for "big structural change" place her decidedly in the second camp, reflected in her policy proposals--from remaking the financial system to calling for putting workers on boards of directors to promoting breaking up monopolies to reshaping housing markets to arguing for redistributing wealth itself through a wealth tax.

Over thirty years ago, Warren was arguing economic redistribution should not be left to budget politics but that policymakers need to be "dealing with the distributive issues that bankruptcy policy implicates" that create unequal wealth in the first place.

Your eyes may glaze-over hearing the words "corporate bankruptcy"--and that's the point. The media tells endless stories of the winners of capitalist competition--the Apples, the Googles, the Exxons--but most firms, especially smaller firms that are never listed on the stock market, DON'T survive so the distribution of their assets in bankruptcy court matters. But that process is arcane and meant to be that way to the advantage of those who benefit from it.

"You see Warren's radical thinking most clearly in her writing on corporate bankruptcy."

Donald Trump epitomizes this reality since multiple firms he has owned have gone through bankruptcy, stiffing creditors and contractors, even as Trump himself leveraged the legal system to shield most of his own personal assets. As Trump himself said when asked about his bankruptcies, "I've taken advantage of the laws of this country."

Documenting how the wealthy like Trump take advantage of the bankruptcy laws to increase economic inequality and how to design the law to promote greater equity has been much of Warren's life work.

Much of the media focus on Elizabeth Warren's political history has justifiably been on her crusade to defend individual debtors from punitive bankruptcy legislation, but you see Warren's radical thinking most clearly in her writing on corporate bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy is actually at the center of our economy, as Warren wrote back in 1992, "The most difficult social problems get dumped into bankruptcy--mass torts, environmental disasters, the dashed expectations of retired employees." The failures of capitalism have to be managed by bankruptcy court judges, as kids in chemotherapy, union workers with empty pensions and bankers square off to divvy up the assets of a belly-up chemical company that poisoned groundwater for multiple communities.

Economists and legal writers like to pretend that the economy is made up just of markets and contracts, but that is a "fiction" according to Warren that lasts only until one party or the other no longer has the money to make good on those promises. At that point, judges in bankruptcy court apply all the "normative issues of fairness ignored in contract law" that Warren argues the business class pretends has no place in economic thinking.

Bankruptcy exists not to further markets but to correct the mistakes that led to bankruptcy happening in the first place--and brings active government concerns for distributional fairness into play. "It provides a forum for negotiating deals, and, ultimately, it allocates the value of a firm to all claimants, making difficult distributional decisions among competing parties."

The dirty secret of corporate law in the U.S. is that corporations are created under state law, not federal law, which leads to a "race to the bottom" as states compete to make their local laws more corporate friendly. Federal bankruptcy is one of the "few aspects of commercial life...addressed in the Constitution," wrote Warren and it overrides some of the worst aspects of state corporate law.

"At the heart of Warren's ideological vision is a clear demand that the market and property rights be subordinate to the human needs and democratic will of the community."

While Warren has sharp criticisms of the federal bankruptcy code, it would be even worse if parties had to "battle for assets under the state law scheme" where banks and other sophisticated creditors would largely be the only ones able to scavenge the carcass of a defunct firm. State law generally gives enhanced collection rights to certain favored creditors: "involuntary creditors, such as tort victims and environmental cleanup funds...would likely come into the claims process only after others had taken the most valuable assets."

The key thing federal bankruptcy law can do that state laws don't is ideally ensure everyone who has potential claims on the assets of the firm get a place at the table when assets of the firm are divided up. Pension holders owed money long into the future get into the same court proceeding with the banks holding immediate debt, "both present and future claims at once" as Warren highlights. With this focus, there is stronger legal emphasis on keeping a firm going as the most effective way to generate ongoing revenue for unpaid obligations. Instead of "inefficient" and "nonproductive strategic behavior" under state debt collection, bankruptcy law is a "collective-action system...to achieve significant cost savings," emphasizing where Warren sees efficiency gains from collective government action over individual market transactions.

While Warren thinks federal bankruptcy law is far superior to dog-eat-dog state asset collection systems, she highlights the way every legal rule in bankruptcy reverberates in the broader economy to shape market decisions, sometimes to the good, more often to the advantage of the wealthy, but never in some "natural" outcome as conservative economic thinkers would have it.

Warren flatly writes: "Any legal rule will cause some redistribution of wealth."

This may be obvious to many progressives, but it challenges the core capitalist legal ideology that law can stand outside the market and be a neutral arbiter of contractual relationships. Instead, Warren sees legal rules as inherently favoring one group over another at every economic point of negotiation: "A rule of ownership, a rule of liability, or a rule of priority will relatively advantage or disadvantage competing parties."

Legal rules are therefore inherently normative, or as Warren wryly observes, "It is not a difference in economic circumstances that dictates that a director of a bankrupt French company is more likely to go to jail than his American counterpart."

Conservative thinkers generally want bankruptcy to focus solely on the "preservation of value for public shareholders and bondholders" but Warren notes that, to its credit, Congress has clearly made redistributional goals to other parties part of the focus of bankruptcy proceedings:

"Virtually every substantive amendment to the Bankruptcy Code since its passage in 1978 has specifically addressed redistributional concerns. The Code is thus designed not only to enhance the value of the failing business, but also to distribute that value among interested parties in specified ways."

Before 1978, the Securities and Exchange Commission had a direct role in overseeing most bankruptcies and that role was largely removed in the law passed that year, argues Warren, precisely because the SEC was seen as too much favoring investors over other stakeholders.

Not that those with economic power regularly lose out in federal bankruptcy court; far from it as Warren repeatedly details in her work. In fact, stakeholders with explicit debt-based contracts with a firm, so-called "secured creditors", consistently get priority by bankruptcy judges, directing resources away from tort victims or others with more diffuse claims. Even where "creditors collectively might be better off with the business as a going concern," Warren writes, "secured creditors can nonetheless insist on liquidation, unless they receive their statutorily protected treatment."

She does detail a few hard-fought for legislative successes against the secured creditors, notably on behalf of workers in bankrupt firms. Statutes have been enacted to give employees owed past due wages priority in bankruptcy court and the law has favored reorganization of firms over liquidation in order to "permit employees to keep their jobs."

Still, despite those exceptions, secured creditors under what are called "full priority rules" win out in most bankruptcy fights because, as Warren argues, they helped write most of the rules. "The group that profits from priority is well-funded and active, fully represented in all the policy debates and in the decision-making bodies. Their representatives are present at every drafting committee meeting and debate on the subject."

At the other end of the spectrum are consumer debtors who "have a perpetual problem" in Warren's words: "they do not have money and they do not organize." Formal consumer groups like the National Consumer Law Center and Consumer Federation of America are "underfunded" and spread over too many issues to compete against the well-financing focus of the financial industry in crafting bankruptcy laws. Grassroots groups with higher degrees of organization like labor and civil rights groups have more of a voice in bankruptcy policy-making but "compared with issues, such as union dues check-offs and affirmative action, bankruptcy was never a top priority," so, as Warren argued, the monied interests with their singular focus and far deeper pockets dominate the process far more of the time.

Warren's diagnosis of the problem of inequality dating back thirty years in her writing is remarkably the same as what she says on the campaign trail now: the solution is not just getting better technocrats running the system but reducing the power of financial interests and increasing the voice and organizing power of average workers and consumers to control what laws get written in the first place.

Warren focuses relentlessly in her work on the role of firms not just as profit-maximizing machines for shareholders--the conservative ideal--but as institutions serving the broader economy, the perpetual focus of progressives promoting industrial planning.

Industrial planning is usually talked about on the left only after firms have shut down in a community--but Warren focuses on bankruptcy law as bringing the broader social values of industrial planning to bear before companies disappear

One key goal in bankruptcy is keeping the firm going. Partly, this enhances the value of its assets to pay off its obligations, but it also serves broader political interests of those outside contract relationships in the market. Warren wrote:

"the revival of an otherwise failing business also serves the distributional interests of many who are not technically "creditors" but who have an interest in a business's continued existence. Older employees who could not have retrained for other jobs, customers who would have to resort to less attractive, alternative suppliers of goods and services, suppliers who would have lost current customers, nearby property owners who would have suffered declining property values, and states or municipalities that would have faced shrinking tax bases benefit from the reorganization's success."

State corporate law and general contract law studiously exclude broader community stakeholders from legal proceedings over corporate decision-making, but federal bankruptcy statutes create a real role for those interests--and Warren makes clear that expanding its focus on those broader community interests when a firm fails should be the priority.

Creditors may want to dismantle the firm to quickly get paid but bankruptcy court, Warren argues, is where government is mandated to step into to protect the values the market ignores.

Repeatedly in her writing, Warren condemns pro-liquidation legal scholars for ignoring these concerns and de facto encouraging government bailouts of those left behind, rather than holding the creditors who financed the failures financially accountable. Even where a firm may not ultimately survive as with bankruptcy proceedings involving asbestos makers like Johns-Manville, Warren details how courts required firms and their creditors to exhaust "their private resources before the government would step in with relief", giving "those who depend on the failing business a chance...to adjust to the losses they will face."

Warren's view of using bankruptcy to protect broader non-market community interests reflects her deep ideological challenge to market economics. Warren argues that markets ignores "parties without legal rights" but we need a legal system to "protect these parties [and] more than the goods that are traded by private contract." Many continuing relationships have not formalized in our economy with market contracts and to "presume either that only contract-based relationships convey value or that only the value of such relationships should be relevant to the policy goals of a legal system ignores this reality."

Warren thirty year ago was a very public combatant with conservative "law and economics" writers, allying publicly with Duncan Kenney and the Critical Legal Studies opponents of the right, equivalent to raising the Red Flag in the legal brawling of the time. As she would argue citing Kennedy in one 1993 piece "the insulation from value judgments that economic analysis offers is illusory." Traditional views of the law just obscured the political choices in the law that favored one group (usually the wealthy) over others

Warren openly mocked the idea that there was any "real" market that law was supposed to try to drive the economy towards. Any attempt to discuss policy "in a perfect market is a Zenlike exercise, much like imagining one hand clasping," so attempts to imagine a "perfect market" were "worth little." As early as 1987, Warren was trashing the economic models of law and economics with their "simple answers" where "economic analysis is utterly self-referential...within a confined, abstract scheme" with no empirical basis in reality.

Conservatives, she wrote, must assume a sufficiently imperfect market for businesses to fail, but a sufficiently perfect market for their "version of a 'market based' solution' to be effective in dealing with those failures. I have difficulty envisioning that market."

Warren's was an empirical critique of how markets function, but it was also a values-based statement that recognizing just the interests of those with property rights in the market would fundamentally be unjust. She rejected market-based bankruptcy schemes as one where those without direct contracts with a firm, including "tort victims, discrimination and harassment complainants, or antitrust plaintiffs, would be left out." A market approach "is overtly distributional in a regressive sense" in redistributing wealth away from those with weak or no property rights claims in the market.

At the heart of Warren's ideological vision is a clear demand that the market and property rights be subordinate to the human needs and democratic will of the community.

Even as the corporate Right has been determined to conquer the courts in order to shape the law to further corporate interests, the liberal movement has been remarkably unfocused on the role of law in promoting economic inequality through the rules of the market.

Liberals have tended to treat battles in the courts as the place where social issues like abortion and gay marriage battles play out, while reserving their energy fighting economic inequality for tax and budget battles. Based on her corporate bankruptcy writings and current proposals, a Warren Presidency, probably even more than a Sanders Presidency, would refocus the liberal-left on how legal rules decide winners and losers in the economy before a widget is produced or a line of code is written.

All her skepticism of markets is reflected in Warren's array of economic plans in her Presidential run which systematically subordinates every market and property rights claim to regulatory supervision. Most on point is her proposed "Accountable Capitalism Act" that would take supervision of large corporations away from the states and put them under federal regulation- and require them to "consider the interests of all corporate stakeholders--including employees, customers, shareholders, and the communities in which the company operates," exactly the broader stakeholder interests usually considered only once companies have failed and gone into bankruptcy court.

Warren may call herself a "capitalist to my bones" but it is a "capitalism" in opposition to the systematic valorization of property rights and market solutions that is currently embedded in our economic and legal system.

Warren has spent decades arguing markets are the legal creation of government rules and argues for far-reaching changes in how that government should design those rules. Whatever you call it, Warren's analysis dating back thirty years and the proposals she now promotes reflects an ideology that would make her orders of magnitude more radical than any President in our history.