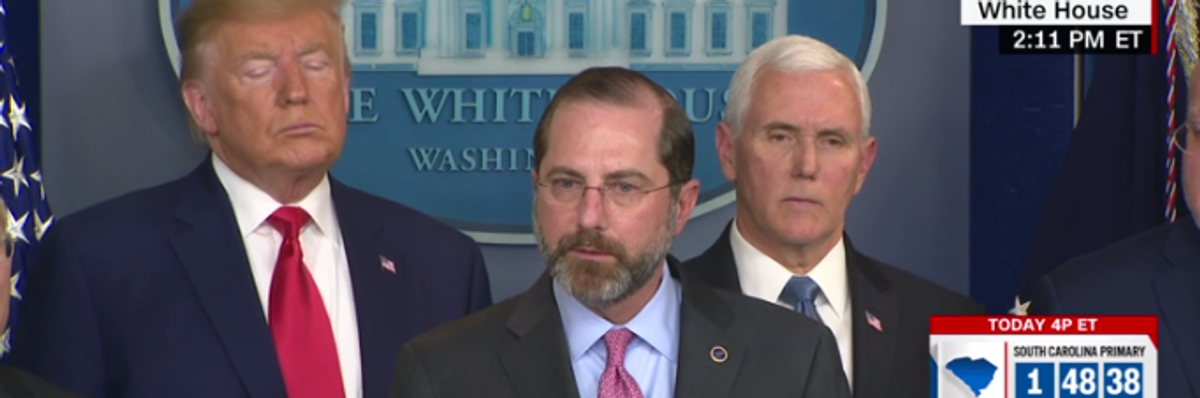

Even in the midst of the most serious epidemic of recent times, Azar's thoughts at his press conference signify he's comfortable with a system that puts corporate profits over public health. (Photo: CNN/Screenshot)

Trump's Ludicrous Handling of the Coronavirus

What Alex Azar appears to be saying is that a coronavirus vaccine, once it is developed, will be left to the private marketplace rather than to government procurement.

The recent statements by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar show the distorted mentality of America's ruling elite. Azar is a typical Trump administration appointment: a drug industry lobbyist and former drug company manager put into a position of responsibility--or perhaps better said, irresponsibility--for public health. Even in the midst of the most serious epidemic of recent times, Azar's thoughts at his press conference signify he's comfortable with a system that puts corporate profits over public health.

Here is Azar's astounding statement regarding the development of a coronavirus vaccine: "Frankly, this has such global attention right now and the private market players, major pharmaceutical players as you've heard, are engaged in this, that we think that this is not like our normal kind of bioterrorism procurement processes, where the government might be the unique purchaser, say, of a smallpox therapy. The market here, we believe, will actually sort that out in terms of demand, purchasing, stocking, etc. But we'll work on that to make sure that we're able to accelerate vaccine as well as therapeutic research and development."

What Azar appears to be saying is that a coronavirus vaccine, once it is developed, will be left to the private marketplace rather than to government procurement. Private businesses, "will actually sort out the demand, purchasing, stocking, etc." In testimony to Congress the following day, Azar was pressed by Illinois Rep. Jan Schakowsky to affirm that a vaccine "would be affordable for anyone who needs it." He replied: "We would want to ensure that we'd work to make it affordable, but we can't control that price because we need the private sector to invest." He is indicating here that the pharmaceutical industry would be setting the price of the vaccine, so the government could not ensure its affordability. This isn't unusual, but can be disastrous in the context of an epidemic.

This is the wrong approach. If we are lucky enough to get an efficacious vaccine in the near future--and, with research, development and testing that will likely take a year or more at best--the vaccine would almost surely need to be rolled out systematically by governments around the world to cover large populations and vulnerable groups in a concerted manner guided by the epidemiology and transmission patterns of the disease. That, after all, is how epidemics are stopped: through concerted public policy and action.

Azar's statement is even more pernicious given the fact that the National Institutes of Health will appropriately be funding much or most of the research. The prevailing model, indeed, in plutocratic America is that taxpayers fund the vast majority of research and development (R&D) for pharmaceuticals and then the intellectual know-how is turned over, free of charge, to private industry so that it can market these drugs under 20 years of patent protection and then make a fortune at the cost of the American people.

It's a racket in full view, one that has been going on for decades, but such are the returns to the astounding lobbying outlays (almost $594 million in 2019) of the health sector.

The right model is a public-health approach. The NIH should indeed lead and substantially fund a massive coronavirus vaccine development effort, as it plans to do. Private companies should then join in under NIH contract or under their own outlays with an advance understanding that they will be paid a royalty by the US government for intellectual property that they contribute to a successful and utilized vaccine.

Almost surely, a successful vaccine will depend heavily or exclusively on the NIH and other public or not-for-profit funding (including private foundations and global cooperation on R&D, for example with China), with some portion of the R&D perhaps coming from private industry.

Once developed, under this public health approach, the vaccine itself would be freely licensed to all manufacturers around the world that offer good manufacturing practices. The funding for the rapid uptake of the vaccine in the world population would be publicly financed in the US and abroad, along with contributions from donor institutions such as the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization.

No, Secretary Azar, it would be ludicrous to leave such operations to private industry. Mr. Secretary, we should not grant patent protection for such a new vaccine produced heavily with public money to fight a global public emergency.

Put the vaccine development in the hands of the extremely able director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Dr. Anthony Fauci, and then put the federal government in the lead of vaccine delivery, including the needed financing. Private industry can be a welcome partner but should operate under clear federal leadership and with no monopoly rights to the vaccine.

It is good to recall the inspiring case of the polio vaccine' development in the middle of the last century. President Franklin Roosevelt, who was diagnosed with polio in 1921, knew that private efforts would never suffice. Even before US public funding for vaccine development was implemented after World War II, FDR invented in 1938 the idea of a not-for-profit institution to lead the effort: the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, known as the March of Dimes.

The March of Dimes funded the basic work of the great pioneer of polio vaccines, Dr. Jonas Salk, who announced the first successful polio vaccine in 1953. The vaccine was introduced in large controlled trials in 1954 covering 1.6 million children in the US, Canada and Finland. In 1955, it went into a mass public immunization campaign. The incidence of polio in the United States fell from 13.9 cases per 100,000 population in 1954 to 0.8 cases per 100,000 in 1961.

When asked by CBS anchor Edward R. Murrow, "Who owns the patent on this vaccine?" Salk famously responded, "Well, the people I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?" That is the public spirit that ended the polio epidemic and it is the public spirit we need to recover in the US to overcome a range of dire challenges, from coronavirus to climate change.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The recent statements by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar show the distorted mentality of America's ruling elite. Azar is a typical Trump administration appointment: a drug industry lobbyist and former drug company manager put into a position of responsibility--or perhaps better said, irresponsibility--for public health. Even in the midst of the most serious epidemic of recent times, Azar's thoughts at his press conference signify he's comfortable with a system that puts corporate profits over public health.

Here is Azar's astounding statement regarding the development of a coronavirus vaccine: "Frankly, this has such global attention right now and the private market players, major pharmaceutical players as you've heard, are engaged in this, that we think that this is not like our normal kind of bioterrorism procurement processes, where the government might be the unique purchaser, say, of a smallpox therapy. The market here, we believe, will actually sort that out in terms of demand, purchasing, stocking, etc. But we'll work on that to make sure that we're able to accelerate vaccine as well as therapeutic research and development."

What Azar appears to be saying is that a coronavirus vaccine, once it is developed, will be left to the private marketplace rather than to government procurement. Private businesses, "will actually sort out the demand, purchasing, stocking, etc." In testimony to Congress the following day, Azar was pressed by Illinois Rep. Jan Schakowsky to affirm that a vaccine "would be affordable for anyone who needs it." He replied: "We would want to ensure that we'd work to make it affordable, but we can't control that price because we need the private sector to invest." He is indicating here that the pharmaceutical industry would be setting the price of the vaccine, so the government could not ensure its affordability. This isn't unusual, but can be disastrous in the context of an epidemic.

This is the wrong approach. If we are lucky enough to get an efficacious vaccine in the near future--and, with research, development and testing that will likely take a year or more at best--the vaccine would almost surely need to be rolled out systematically by governments around the world to cover large populations and vulnerable groups in a concerted manner guided by the epidemiology and transmission patterns of the disease. That, after all, is how epidemics are stopped: through concerted public policy and action.

Azar's statement is even more pernicious given the fact that the National Institutes of Health will appropriately be funding much or most of the research. The prevailing model, indeed, in plutocratic America is that taxpayers fund the vast majority of research and development (R&D) for pharmaceuticals and then the intellectual know-how is turned over, free of charge, to private industry so that it can market these drugs under 20 years of patent protection and then make a fortune at the cost of the American people.

It's a racket in full view, one that has been going on for decades, but such are the returns to the astounding lobbying outlays (almost $594 million in 2019) of the health sector.

The right model is a public-health approach. The NIH should indeed lead and substantially fund a massive coronavirus vaccine development effort, as it plans to do. Private companies should then join in under NIH contract or under their own outlays with an advance understanding that they will be paid a royalty by the US government for intellectual property that they contribute to a successful and utilized vaccine.

Almost surely, a successful vaccine will depend heavily or exclusively on the NIH and other public or not-for-profit funding (including private foundations and global cooperation on R&D, for example with China), with some portion of the R&D perhaps coming from private industry.

Once developed, under this public health approach, the vaccine itself would be freely licensed to all manufacturers around the world that offer good manufacturing practices. The funding for the rapid uptake of the vaccine in the world population would be publicly financed in the US and abroad, along with contributions from donor institutions such as the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization.

No, Secretary Azar, it would be ludicrous to leave such operations to private industry. Mr. Secretary, we should not grant patent protection for such a new vaccine produced heavily with public money to fight a global public emergency.

Put the vaccine development in the hands of the extremely able director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Dr. Anthony Fauci, and then put the federal government in the lead of vaccine delivery, including the needed financing. Private industry can be a welcome partner but should operate under clear federal leadership and with no monopoly rights to the vaccine.

It is good to recall the inspiring case of the polio vaccine' development in the middle of the last century. President Franklin Roosevelt, who was diagnosed with polio in 1921, knew that private efforts would never suffice. Even before US public funding for vaccine development was implemented after World War II, FDR invented in 1938 the idea of a not-for-profit institution to lead the effort: the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, known as the March of Dimes.

The March of Dimes funded the basic work of the great pioneer of polio vaccines, Dr. Jonas Salk, who announced the first successful polio vaccine in 1953. The vaccine was introduced in large controlled trials in 1954 covering 1.6 million children in the US, Canada and Finland. In 1955, it went into a mass public immunization campaign. The incidence of polio in the United States fell from 13.9 cases per 100,000 population in 1954 to 0.8 cases per 100,000 in 1961.

When asked by CBS anchor Edward R. Murrow, "Who owns the patent on this vaccine?" Salk famously responded, "Well, the people I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?" That is the public spirit that ended the polio epidemic and it is the public spirit we need to recover in the US to overcome a range of dire challenges, from coronavirus to climate change.

The recent statements by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar show the distorted mentality of America's ruling elite. Azar is a typical Trump administration appointment: a drug industry lobbyist and former drug company manager put into a position of responsibility--or perhaps better said, irresponsibility--for public health. Even in the midst of the most serious epidemic of recent times, Azar's thoughts at his press conference signify he's comfortable with a system that puts corporate profits over public health.

Here is Azar's astounding statement regarding the development of a coronavirus vaccine: "Frankly, this has such global attention right now and the private market players, major pharmaceutical players as you've heard, are engaged in this, that we think that this is not like our normal kind of bioterrorism procurement processes, where the government might be the unique purchaser, say, of a smallpox therapy. The market here, we believe, will actually sort that out in terms of demand, purchasing, stocking, etc. But we'll work on that to make sure that we're able to accelerate vaccine as well as therapeutic research and development."

What Azar appears to be saying is that a coronavirus vaccine, once it is developed, will be left to the private marketplace rather than to government procurement. Private businesses, "will actually sort out the demand, purchasing, stocking, etc." In testimony to Congress the following day, Azar was pressed by Illinois Rep. Jan Schakowsky to affirm that a vaccine "would be affordable for anyone who needs it." He replied: "We would want to ensure that we'd work to make it affordable, but we can't control that price because we need the private sector to invest." He is indicating here that the pharmaceutical industry would be setting the price of the vaccine, so the government could not ensure its affordability. This isn't unusual, but can be disastrous in the context of an epidemic.

This is the wrong approach. If we are lucky enough to get an efficacious vaccine in the near future--and, with research, development and testing that will likely take a year or more at best--the vaccine would almost surely need to be rolled out systematically by governments around the world to cover large populations and vulnerable groups in a concerted manner guided by the epidemiology and transmission patterns of the disease. That, after all, is how epidemics are stopped: through concerted public policy and action.

Azar's statement is even more pernicious given the fact that the National Institutes of Health will appropriately be funding much or most of the research. The prevailing model, indeed, in plutocratic America is that taxpayers fund the vast majority of research and development (R&D) for pharmaceuticals and then the intellectual know-how is turned over, free of charge, to private industry so that it can market these drugs under 20 years of patent protection and then make a fortune at the cost of the American people.

It's a racket in full view, one that has been going on for decades, but such are the returns to the astounding lobbying outlays (almost $594 million in 2019) of the health sector.

The right model is a public-health approach. The NIH should indeed lead and substantially fund a massive coronavirus vaccine development effort, as it plans to do. Private companies should then join in under NIH contract or under their own outlays with an advance understanding that they will be paid a royalty by the US government for intellectual property that they contribute to a successful and utilized vaccine.

Almost surely, a successful vaccine will depend heavily or exclusively on the NIH and other public or not-for-profit funding (including private foundations and global cooperation on R&D, for example with China), with some portion of the R&D perhaps coming from private industry.

Once developed, under this public health approach, the vaccine itself would be freely licensed to all manufacturers around the world that offer good manufacturing practices. The funding for the rapid uptake of the vaccine in the world population would be publicly financed in the US and abroad, along with contributions from donor institutions such as the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization.

No, Secretary Azar, it would be ludicrous to leave such operations to private industry. Mr. Secretary, we should not grant patent protection for such a new vaccine produced heavily with public money to fight a global public emergency.

Put the vaccine development in the hands of the extremely able director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Dr. Anthony Fauci, and then put the federal government in the lead of vaccine delivery, including the needed financing. Private industry can be a welcome partner but should operate under clear federal leadership and with no monopoly rights to the vaccine.

It is good to recall the inspiring case of the polio vaccine' development in the middle of the last century. President Franklin Roosevelt, who was diagnosed with polio in 1921, knew that private efforts would never suffice. Even before US public funding for vaccine development was implemented after World War II, FDR invented in 1938 the idea of a not-for-profit institution to lead the effort: the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, known as the March of Dimes.

The March of Dimes funded the basic work of the great pioneer of polio vaccines, Dr. Jonas Salk, who announced the first successful polio vaccine in 1953. The vaccine was introduced in large controlled trials in 1954 covering 1.6 million children in the US, Canada and Finland. In 1955, it went into a mass public immunization campaign. The incidence of polio in the United States fell from 13.9 cases per 100,000 population in 1954 to 0.8 cases per 100,000 in 1961.

When asked by CBS anchor Edward R. Murrow, "Who owns the patent on this vaccine?" Salk famously responded, "Well, the people I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?" That is the public spirit that ended the polio epidemic and it is the public spirit we need to recover in the US to overcome a range of dire challenges, from coronavirus to climate change.