Being better than the worst is not good enough in a time of climate emergency. (Photo: Mike Mozart/Flickr/cc)

The Loopholes Lurking in BP's New Climate Aims

It’s time for BP and all oil companies to stop hiding behind net-zero rhetoric and commit to immediate action on the scale of the crisis we’re in.

This post is co-authored by Emily Bugden and Kelly Trout

Last month, in response to mounting pressure from investors, BP's new CEO Bernard Looney announced his ten climate action aims for the company, with the overall goal of making BP a "net zero company by 2050 or sooner."

Fast forward to mid-March and oil markets are at their most volatile point in five years. We can't predict how the sudden collapse of oil prices, and resulting fall of BP and other industry stocks may affect the company's aims and activities. But we can expect that investors will be taking an even harder look at whether the climate strategies of BP and other oil majors credibly address the escalating global crises we face.

Our initial analysis, has uncovered a number of gaps and loopholes lurking in BP's net-zero aims. Without an immediate commitment to stop drilling into new oil and gas reserves, and a credible plan to begin phasing out extraction within this decade, BP's commitment will fall dangerously short of the measures needed to align with the Paris Agreement and credibly address the climate emergency.

Before digging deeper into the details, it's important to note: BP's commitments warrant tough scrutiny because BP has a dirty track record. Of investor-owned companies, BP ranks third in the cumulative carbon pollution associated with its business since 1965. A report released by InfluenceMap last year shows that, since the Paris Agreement was signed, BP has spent the most of all oil majors on lobbying to obstruct climate action. As of 2019, the company was on track to invest a further USD 71 billion in developing new oil and gas fields over the coming decade.

What is BP saying?

In its plan, BP pledges to reach net zero emissions across both its operations and from the oil and gas it extracts from the ground, to halve the carbon intensity of products it sells, and to increase investment in low- and no-carbon products, all by 2050. It also makes commitments to advocate for a carbon price and exit trade associations which don't align with its views on climate.

At first glance, these aims go further than some of BP's peers. For example, the recent "net zero" pledges from Equinor and Cenovus only cover the carbon pollution those companies emit from their operations in Norway and Canada respectively. They omit the largest cause of industry pollution: the ultimate burning of the oil and gas extracted from those operations. Shell has pledged to cut the "net carbon footprint" of the oil and gas it extracts and sells in half by 2050, which, as OCI has previously analysed, could still allow Shell to increase its actual total emissions.

BP is clearly feeling the mounting public pressure to take meaningful action on the climate crisis. But, as we unpack below, that does not mean BP is committing to the scale of action required. Being better than the worst is not good enough in a time of climate emergency.

What do the Paris goals require?

The latest climate science shows us that reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050 is key to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (degC), but that alone is not enough. The pace and means by which we do it, and the resulting cumulative levels of heat-trapping pollution that reach our atmosphere, will determine how far temperatures rise.

Hannah McKinnon, director of the Energy Transitions and Futures program at Oil Change International, said in response to Looney's announcement, "BP is not committing to what's needed, which is a rapid phase-out of oil and gas production in line with climate justice and climate science [...] Instead, BP continues to invest massively in looking for and expanding into new fossil fuel reserves, this keeps them on the wrong side of history."

Previous OCI analysis has shown that fossil fuel companies already have more oil, gas, and coal under production - in currently operating fields and mines - than we can afford to burn under the Paris Agreement. A key solution to containing the climate crisis is for companies like BP to stop exploring for and developing more oil and gas reserves. Once a company develops new reserves, political, economic, and legal factors create inertia behind their continued production, a problem called carbon lock-in.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also makes clear in its Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5degC that early action is critical if we're going to stay within 1.5degC without large-scale reliance on technologies to suck extra carbon dioxide out of the air. The report warns that depending on massive deployment of so-called negative emissions technologies is a "major risk." The IPCC report highlights four illustrative pathways that represent different societal choices for limiting warming to 1.5oC. In the path that does not rely on unproven carbon-dioxide removal technologies, oil would decline by 37% and gas by 25% by 2030, compared to 2010 levels.

The phase-out of oil and gas needs to start now, but BP's new aims do not include any specific commitment to lead the way in this decade.

As Charlie Kronick, Oil Advisor at Greenpeace UK, said: "BP's 'ambitions' and 'aims' all seem to apply to Looney's successors, and leave the urgent questions unanswered. How will they reach net zero? [...] When will they stop wasting billions on drilling for new oil and gas we can't burn? What is the scale and schedule for the renewables investment they barely mention? And what are they going to do this decade, when the battle to protect our climate will be won or lost."

The loopholes lurking in BP's aims

Looney has pledged more details about how BP will meet its new climate aims this September. We hope BP will then include meaningful commitments - to stop drilling for new oil and gas, and to begin a rapid phase down of extraction over the critical next decade.

However, even without the full details, we can already identify key ways in which BP is cutting corners. If BP CEO Bernard Looney really means what he said last month - "the world does have a carbon budget, it is finite, and it is running out fast, and we need a rapid transition to net-zero" - then BP's current aims to 2050 are far from sufficient.

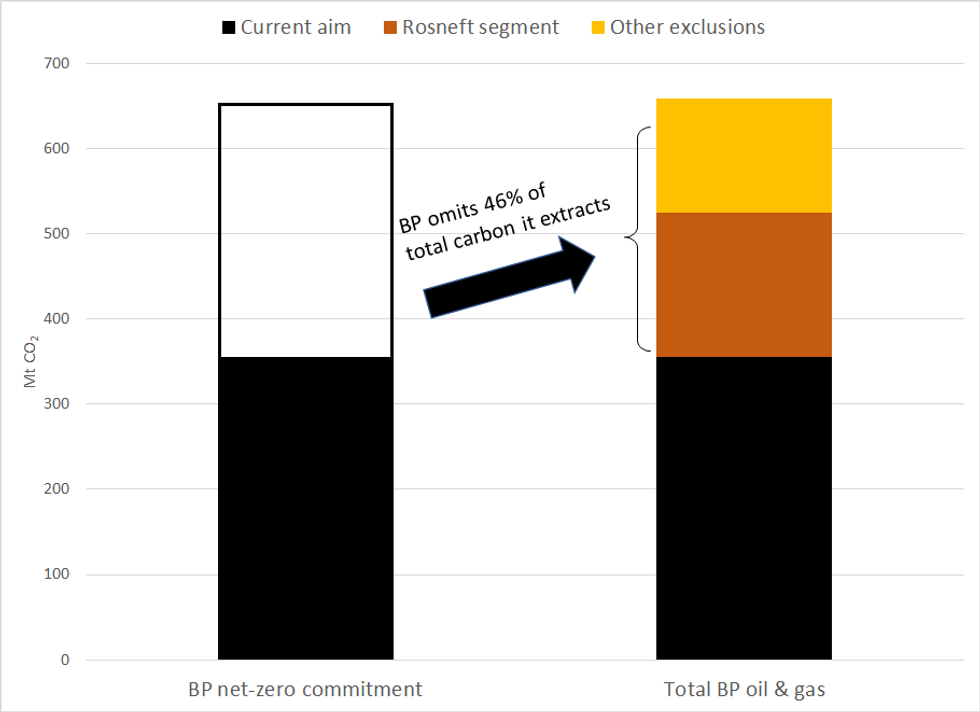

Omitting nearly half of upstream production: BP has committed to be "net zero on an absolute basis across the carbon in our upstream oil and gas production by 2050 or sooner." But when you read the fine print, BP is excluding a large portion of the carbon it extracts from that commitment.

BP's accounting of its production excludes any oil and gas that it produces but does not sell (due to royalties or from burning it in its own operations). BP also excludes the production related to its 20% stake in Russia-based oil company Rosneft. We estimate that these accounting loopholes exclude from BP's net zero aim 46% of the total carbon that the company invested in extracting in 2018 (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Total CO2 Emissions Attributable to Oil & Gas BP Extracted in 2018 vs. Emissions Covered by BP's Net-Zero Aim

Sources: BP, Rystad Energy

Note: Like BP, we account for production on an equity basis; the total includes production from assets in which BP owns a minority interest.

No commitment to reduce its sales of oil and gas: On the question of what gets burned, BP has carved out another loophole for itself: it is not pledging to go net zero on the oil and gas that it sells downstream to customers but does not produce upstream itself. As the Financial Times has reported, this cuts out "more than half the total, with its sales volumes reaching 8.6m barrels a day in 2018, while its production of oil and gas totalled 2.7m barrels of oil equivalent a day." Those figures again exclude BP's stake in Rosneft. BP has pledged to halve the "carbon intensity" of products it sells, but this does not guarantee any reduction in absolute emissions.

Ultimately, the climate does not care whether BP maintains separate financial accounting for its Rosneft segment or how it divides up its sales and production. What matters for the climate is the total amount of carbon that BP is aiding in extracting and burning - and BP's current aims omit a significant portion of it.

Gambling on risky, unproven technologies: The Washington Post has noted that BP's net-zero pledge "assumes that it would still produce oil and gas in 2050, with those emissions offset by technologies that might suck carbon dioxide from the air." These negative emissions technologies could include afforestation and reforestation and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), which is still unproven at scale.

Fossil fuel majors are often eager advocates for NETs. Why? Negative emissions allow them to create "climate" scenarios in which they can keep expanding fossil fuel extraction into the medium-term future. They simply assume that unproven technologies or mass planting of trees will suck the excess pollution back out of the atmosphere at a later date.

As OCI has previously explained, however, gambling our climate goals on assumptions about future NETs is hugely problematic. It entails delaying meaningful near-term action in favor of an escape hatch that may never materialize, or may fail. The IPCC's 1.5degC report cautions that large-scale deployment of NETs may not be socially desirable, equitable, or technically feasible, and that there is no guarantee that it will be effective.

What would a meaningful climate commitment from BP look like?

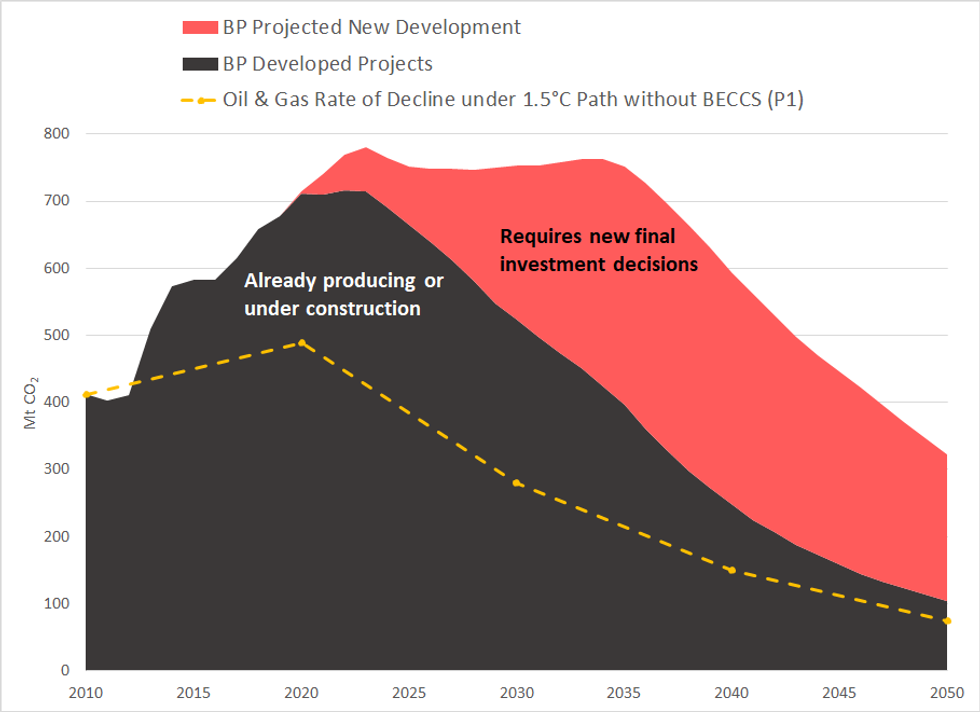

Figure 2 below gives a sense of what a serious commitment to the Paris goals would look like for BP. It shows Rystad Energy's projection of BP's production to 2050, based on the company's existing plans, against the rate of decline for oil and gas use under the most precautionary illustrative 1.5oC energy pathway included in the IPCC special report (P1, which excludes BECCS).

If BP is serious about aligning with the full ambition of the Paris Agreement, the company's investment in new exploration and expansion would need to stop today. More than that, it would need to decide which already-developed projects it will shut down early.

Figure 2: Projected CO2 Emissions from BP Oil and Gas, with and without New Development, vs. 1.5oC Rate of Oil and Gas Decline

Sources: Rystad Energy, IPCC

Note: Based on BP's projected production on an equity basis, including BP's Rosneft segment and assets in which it has minority interests. The rate of oil and gas decline is taken from the P1 illustrative pathway included in the IPCC Special Report on 1.5C. This pathway is used because it does not rely on unproven negative emissions technologies (bioenergy with carbon capture and storage).

Ultimately, we need to hear less about BP's aims for 2050 and more about what BP plans to do in this decade to begin meaningfully declining all aspects of its oil and gas operations. When BP releases the details of its net zero aims this September, we'll be grading them according to these critical questions, and more:

- Will BP close the loopholes in its existing aims, and take responsibility for all the carbon it extracts from the ground and sells?

- Will BP immediately halt its current pipeline of projects pending exploration and development?

- Will BP continue to rely on risky negative emissions technologies to justify fossil fuel expansion, or will the company wind down its production at a pace aligned with limiting warming to 1.5oC?

It's time for BP and all oil companies to stop hiding behind net-zero rhetoric and commit to immediate action on the scale of the crisis we're in.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

This post is co-authored by Emily Bugden and Kelly Trout

Last month, in response to mounting pressure from investors, BP's new CEO Bernard Looney announced his ten climate action aims for the company, with the overall goal of making BP a "net zero company by 2050 or sooner."

Fast forward to mid-March and oil markets are at their most volatile point in five years. We can't predict how the sudden collapse of oil prices, and resulting fall of BP and other industry stocks may affect the company's aims and activities. But we can expect that investors will be taking an even harder look at whether the climate strategies of BP and other oil majors credibly address the escalating global crises we face.

Our initial analysis, has uncovered a number of gaps and loopholes lurking in BP's net-zero aims. Without an immediate commitment to stop drilling into new oil and gas reserves, and a credible plan to begin phasing out extraction within this decade, BP's commitment will fall dangerously short of the measures needed to align with the Paris Agreement and credibly address the climate emergency.

Before digging deeper into the details, it's important to note: BP's commitments warrant tough scrutiny because BP has a dirty track record. Of investor-owned companies, BP ranks third in the cumulative carbon pollution associated with its business since 1965. A report released by InfluenceMap last year shows that, since the Paris Agreement was signed, BP has spent the most of all oil majors on lobbying to obstruct climate action. As of 2019, the company was on track to invest a further USD 71 billion in developing new oil and gas fields over the coming decade.

What is BP saying?

In its plan, BP pledges to reach net zero emissions across both its operations and from the oil and gas it extracts from the ground, to halve the carbon intensity of products it sells, and to increase investment in low- and no-carbon products, all by 2050. It also makes commitments to advocate for a carbon price and exit trade associations which don't align with its views on climate.

At first glance, these aims go further than some of BP's peers. For example, the recent "net zero" pledges from Equinor and Cenovus only cover the carbon pollution those companies emit from their operations in Norway and Canada respectively. They omit the largest cause of industry pollution: the ultimate burning of the oil and gas extracted from those operations. Shell has pledged to cut the "net carbon footprint" of the oil and gas it extracts and sells in half by 2050, which, as OCI has previously analysed, could still allow Shell to increase its actual total emissions.

BP is clearly feeling the mounting public pressure to take meaningful action on the climate crisis. But, as we unpack below, that does not mean BP is committing to the scale of action required. Being better than the worst is not good enough in a time of climate emergency.

What do the Paris goals require?

The latest climate science shows us that reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050 is key to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (degC), but that alone is not enough. The pace and means by which we do it, and the resulting cumulative levels of heat-trapping pollution that reach our atmosphere, will determine how far temperatures rise.

Hannah McKinnon, director of the Energy Transitions and Futures program at Oil Change International, said in response to Looney's announcement, "BP is not committing to what's needed, which is a rapid phase-out of oil and gas production in line with climate justice and climate science [...] Instead, BP continues to invest massively in looking for and expanding into new fossil fuel reserves, this keeps them on the wrong side of history."

Previous OCI analysis has shown that fossil fuel companies already have more oil, gas, and coal under production - in currently operating fields and mines - than we can afford to burn under the Paris Agreement. A key solution to containing the climate crisis is for companies like BP to stop exploring for and developing more oil and gas reserves. Once a company develops new reserves, political, economic, and legal factors create inertia behind their continued production, a problem called carbon lock-in.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also makes clear in its Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5degC that early action is critical if we're going to stay within 1.5degC without large-scale reliance on technologies to suck extra carbon dioxide out of the air. The report warns that depending on massive deployment of so-called negative emissions technologies is a "major risk." The IPCC report highlights four illustrative pathways that represent different societal choices for limiting warming to 1.5oC. In the path that does not rely on unproven carbon-dioxide removal technologies, oil would decline by 37% and gas by 25% by 2030, compared to 2010 levels.

The phase-out of oil and gas needs to start now, but BP's new aims do not include any specific commitment to lead the way in this decade.

As Charlie Kronick, Oil Advisor at Greenpeace UK, said: "BP's 'ambitions' and 'aims' all seem to apply to Looney's successors, and leave the urgent questions unanswered. How will they reach net zero? [...] When will they stop wasting billions on drilling for new oil and gas we can't burn? What is the scale and schedule for the renewables investment they barely mention? And what are they going to do this decade, when the battle to protect our climate will be won or lost."

The loopholes lurking in BP's aims

Looney has pledged more details about how BP will meet its new climate aims this September. We hope BP will then include meaningful commitments - to stop drilling for new oil and gas, and to begin a rapid phase down of extraction over the critical next decade.

However, even without the full details, we can already identify key ways in which BP is cutting corners. If BP CEO Bernard Looney really means what he said last month - "the world does have a carbon budget, it is finite, and it is running out fast, and we need a rapid transition to net-zero" - then BP's current aims to 2050 are far from sufficient.

Omitting nearly half of upstream production: BP has committed to be "net zero on an absolute basis across the carbon in our upstream oil and gas production by 2050 or sooner." But when you read the fine print, BP is excluding a large portion of the carbon it extracts from that commitment.

BP's accounting of its production excludes any oil and gas that it produces but does not sell (due to royalties or from burning it in its own operations). BP also excludes the production related to its 20% stake in Russia-based oil company Rosneft. We estimate that these accounting loopholes exclude from BP's net zero aim 46% of the total carbon that the company invested in extracting in 2018 (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Total CO2 Emissions Attributable to Oil & Gas BP Extracted in 2018 vs. Emissions Covered by BP's Net-Zero Aim

Sources: BP, Rystad Energy

Note: Like BP, we account for production on an equity basis; the total includes production from assets in which BP owns a minority interest.

No commitment to reduce its sales of oil and gas: On the question of what gets burned, BP has carved out another loophole for itself: it is not pledging to go net zero on the oil and gas that it sells downstream to customers but does not produce upstream itself. As the Financial Times has reported, this cuts out "more than half the total, with its sales volumes reaching 8.6m barrels a day in 2018, while its production of oil and gas totalled 2.7m barrels of oil equivalent a day." Those figures again exclude BP's stake in Rosneft. BP has pledged to halve the "carbon intensity" of products it sells, but this does not guarantee any reduction in absolute emissions.

Ultimately, the climate does not care whether BP maintains separate financial accounting for its Rosneft segment or how it divides up its sales and production. What matters for the climate is the total amount of carbon that BP is aiding in extracting and burning - and BP's current aims omit a significant portion of it.

Gambling on risky, unproven technologies: The Washington Post has noted that BP's net-zero pledge "assumes that it would still produce oil and gas in 2050, with those emissions offset by technologies that might suck carbon dioxide from the air." These negative emissions technologies could include afforestation and reforestation and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), which is still unproven at scale.

Fossil fuel majors are often eager advocates for NETs. Why? Negative emissions allow them to create "climate" scenarios in which they can keep expanding fossil fuel extraction into the medium-term future. They simply assume that unproven technologies or mass planting of trees will suck the excess pollution back out of the atmosphere at a later date.

As OCI has previously explained, however, gambling our climate goals on assumptions about future NETs is hugely problematic. It entails delaying meaningful near-term action in favor of an escape hatch that may never materialize, or may fail. The IPCC's 1.5degC report cautions that large-scale deployment of NETs may not be socially desirable, equitable, or technically feasible, and that there is no guarantee that it will be effective.

What would a meaningful climate commitment from BP look like?

Figure 2 below gives a sense of what a serious commitment to the Paris goals would look like for BP. It shows Rystad Energy's projection of BP's production to 2050, based on the company's existing plans, against the rate of decline for oil and gas use under the most precautionary illustrative 1.5oC energy pathway included in the IPCC special report (P1, which excludes BECCS).

If BP is serious about aligning with the full ambition of the Paris Agreement, the company's investment in new exploration and expansion would need to stop today. More than that, it would need to decide which already-developed projects it will shut down early.

Figure 2: Projected CO2 Emissions from BP Oil and Gas, with and without New Development, vs. 1.5oC Rate of Oil and Gas Decline

Sources: Rystad Energy, IPCC

Note: Based on BP's projected production on an equity basis, including BP's Rosneft segment and assets in which it has minority interests. The rate of oil and gas decline is taken from the P1 illustrative pathway included in the IPCC Special Report on 1.5C. This pathway is used because it does not rely on unproven negative emissions technologies (bioenergy with carbon capture and storage).

Ultimately, we need to hear less about BP's aims for 2050 and more about what BP plans to do in this decade to begin meaningfully declining all aspects of its oil and gas operations. When BP releases the details of its net zero aims this September, we'll be grading them according to these critical questions, and more:

- Will BP close the loopholes in its existing aims, and take responsibility for all the carbon it extracts from the ground and sells?

- Will BP immediately halt its current pipeline of projects pending exploration and development?

- Will BP continue to rely on risky negative emissions technologies to justify fossil fuel expansion, or will the company wind down its production at a pace aligned with limiting warming to 1.5oC?

It's time for BP and all oil companies to stop hiding behind net-zero rhetoric and commit to immediate action on the scale of the crisis we're in.

This post is co-authored by Emily Bugden and Kelly Trout

Last month, in response to mounting pressure from investors, BP's new CEO Bernard Looney announced his ten climate action aims for the company, with the overall goal of making BP a "net zero company by 2050 or sooner."

Fast forward to mid-March and oil markets are at their most volatile point in five years. We can't predict how the sudden collapse of oil prices, and resulting fall of BP and other industry stocks may affect the company's aims and activities. But we can expect that investors will be taking an even harder look at whether the climate strategies of BP and other oil majors credibly address the escalating global crises we face.

Our initial analysis, has uncovered a number of gaps and loopholes lurking in BP's net-zero aims. Without an immediate commitment to stop drilling into new oil and gas reserves, and a credible plan to begin phasing out extraction within this decade, BP's commitment will fall dangerously short of the measures needed to align with the Paris Agreement and credibly address the climate emergency.

Before digging deeper into the details, it's important to note: BP's commitments warrant tough scrutiny because BP has a dirty track record. Of investor-owned companies, BP ranks third in the cumulative carbon pollution associated with its business since 1965. A report released by InfluenceMap last year shows that, since the Paris Agreement was signed, BP has spent the most of all oil majors on lobbying to obstruct climate action. As of 2019, the company was on track to invest a further USD 71 billion in developing new oil and gas fields over the coming decade.

What is BP saying?

In its plan, BP pledges to reach net zero emissions across both its operations and from the oil and gas it extracts from the ground, to halve the carbon intensity of products it sells, and to increase investment in low- and no-carbon products, all by 2050. It also makes commitments to advocate for a carbon price and exit trade associations which don't align with its views on climate.

At first glance, these aims go further than some of BP's peers. For example, the recent "net zero" pledges from Equinor and Cenovus only cover the carbon pollution those companies emit from their operations in Norway and Canada respectively. They omit the largest cause of industry pollution: the ultimate burning of the oil and gas extracted from those operations. Shell has pledged to cut the "net carbon footprint" of the oil and gas it extracts and sells in half by 2050, which, as OCI has previously analysed, could still allow Shell to increase its actual total emissions.

BP is clearly feeling the mounting public pressure to take meaningful action on the climate crisis. But, as we unpack below, that does not mean BP is committing to the scale of action required. Being better than the worst is not good enough in a time of climate emergency.

What do the Paris goals require?

The latest climate science shows us that reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050 is key to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (degC), but that alone is not enough. The pace and means by which we do it, and the resulting cumulative levels of heat-trapping pollution that reach our atmosphere, will determine how far temperatures rise.

Hannah McKinnon, director of the Energy Transitions and Futures program at Oil Change International, said in response to Looney's announcement, "BP is not committing to what's needed, which is a rapid phase-out of oil and gas production in line with climate justice and climate science [...] Instead, BP continues to invest massively in looking for and expanding into new fossil fuel reserves, this keeps them on the wrong side of history."

Previous OCI analysis has shown that fossil fuel companies already have more oil, gas, and coal under production - in currently operating fields and mines - than we can afford to burn under the Paris Agreement. A key solution to containing the climate crisis is for companies like BP to stop exploring for and developing more oil and gas reserves. Once a company develops new reserves, political, economic, and legal factors create inertia behind their continued production, a problem called carbon lock-in.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also makes clear in its Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5degC that early action is critical if we're going to stay within 1.5degC without large-scale reliance on technologies to suck extra carbon dioxide out of the air. The report warns that depending on massive deployment of so-called negative emissions technologies is a "major risk." The IPCC report highlights four illustrative pathways that represent different societal choices for limiting warming to 1.5oC. In the path that does not rely on unproven carbon-dioxide removal technologies, oil would decline by 37% and gas by 25% by 2030, compared to 2010 levels.

The phase-out of oil and gas needs to start now, but BP's new aims do not include any specific commitment to lead the way in this decade.

As Charlie Kronick, Oil Advisor at Greenpeace UK, said: "BP's 'ambitions' and 'aims' all seem to apply to Looney's successors, and leave the urgent questions unanswered. How will they reach net zero? [...] When will they stop wasting billions on drilling for new oil and gas we can't burn? What is the scale and schedule for the renewables investment they barely mention? And what are they going to do this decade, when the battle to protect our climate will be won or lost."

The loopholes lurking in BP's aims

Looney has pledged more details about how BP will meet its new climate aims this September. We hope BP will then include meaningful commitments - to stop drilling for new oil and gas, and to begin a rapid phase down of extraction over the critical next decade.

However, even without the full details, we can already identify key ways in which BP is cutting corners. If BP CEO Bernard Looney really means what he said last month - "the world does have a carbon budget, it is finite, and it is running out fast, and we need a rapid transition to net-zero" - then BP's current aims to 2050 are far from sufficient.

Omitting nearly half of upstream production: BP has committed to be "net zero on an absolute basis across the carbon in our upstream oil and gas production by 2050 or sooner." But when you read the fine print, BP is excluding a large portion of the carbon it extracts from that commitment.

BP's accounting of its production excludes any oil and gas that it produces but does not sell (due to royalties or from burning it in its own operations). BP also excludes the production related to its 20% stake in Russia-based oil company Rosneft. We estimate that these accounting loopholes exclude from BP's net zero aim 46% of the total carbon that the company invested in extracting in 2018 (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Total CO2 Emissions Attributable to Oil & Gas BP Extracted in 2018 vs. Emissions Covered by BP's Net-Zero Aim

Sources: BP, Rystad Energy

Note: Like BP, we account for production on an equity basis; the total includes production from assets in which BP owns a minority interest.

No commitment to reduce its sales of oil and gas: On the question of what gets burned, BP has carved out another loophole for itself: it is not pledging to go net zero on the oil and gas that it sells downstream to customers but does not produce upstream itself. As the Financial Times has reported, this cuts out "more than half the total, with its sales volumes reaching 8.6m barrels a day in 2018, while its production of oil and gas totalled 2.7m barrels of oil equivalent a day." Those figures again exclude BP's stake in Rosneft. BP has pledged to halve the "carbon intensity" of products it sells, but this does not guarantee any reduction in absolute emissions.

Ultimately, the climate does not care whether BP maintains separate financial accounting for its Rosneft segment or how it divides up its sales and production. What matters for the climate is the total amount of carbon that BP is aiding in extracting and burning - and BP's current aims omit a significant portion of it.

Gambling on risky, unproven technologies: The Washington Post has noted that BP's net-zero pledge "assumes that it would still produce oil and gas in 2050, with those emissions offset by technologies that might suck carbon dioxide from the air." These negative emissions technologies could include afforestation and reforestation and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), which is still unproven at scale.

Fossil fuel majors are often eager advocates for NETs. Why? Negative emissions allow them to create "climate" scenarios in which they can keep expanding fossil fuel extraction into the medium-term future. They simply assume that unproven technologies or mass planting of trees will suck the excess pollution back out of the atmosphere at a later date.

As OCI has previously explained, however, gambling our climate goals on assumptions about future NETs is hugely problematic. It entails delaying meaningful near-term action in favor of an escape hatch that may never materialize, or may fail. The IPCC's 1.5degC report cautions that large-scale deployment of NETs may not be socially desirable, equitable, or technically feasible, and that there is no guarantee that it will be effective.

What would a meaningful climate commitment from BP look like?

Figure 2 below gives a sense of what a serious commitment to the Paris goals would look like for BP. It shows Rystad Energy's projection of BP's production to 2050, based on the company's existing plans, against the rate of decline for oil and gas use under the most precautionary illustrative 1.5oC energy pathway included in the IPCC special report (P1, which excludes BECCS).

If BP is serious about aligning with the full ambition of the Paris Agreement, the company's investment in new exploration and expansion would need to stop today. More than that, it would need to decide which already-developed projects it will shut down early.

Figure 2: Projected CO2 Emissions from BP Oil and Gas, with and without New Development, vs. 1.5oC Rate of Oil and Gas Decline

Sources: Rystad Energy, IPCC

Note: Based on BP's projected production on an equity basis, including BP's Rosneft segment and assets in which it has minority interests. The rate of oil and gas decline is taken from the P1 illustrative pathway included in the IPCC Special Report on 1.5C. This pathway is used because it does not rely on unproven negative emissions technologies (bioenergy with carbon capture and storage).

Ultimately, we need to hear less about BP's aims for 2050 and more about what BP plans to do in this decade to begin meaningfully declining all aspects of its oil and gas operations. When BP releases the details of its net zero aims this September, we'll be grading them according to these critical questions, and more:

- Will BP close the loopholes in its existing aims, and take responsibility for all the carbon it extracts from the ground and sells?

- Will BP immediately halt its current pipeline of projects pending exploration and development?

- Will BP continue to rely on risky negative emissions technologies to justify fossil fuel expansion, or will the company wind down its production at a pace aligned with limiting warming to 1.5oC?

It's time for BP and all oil companies to stop hiding behind net-zero rhetoric and commit to immediate action on the scale of the crisis we're in.