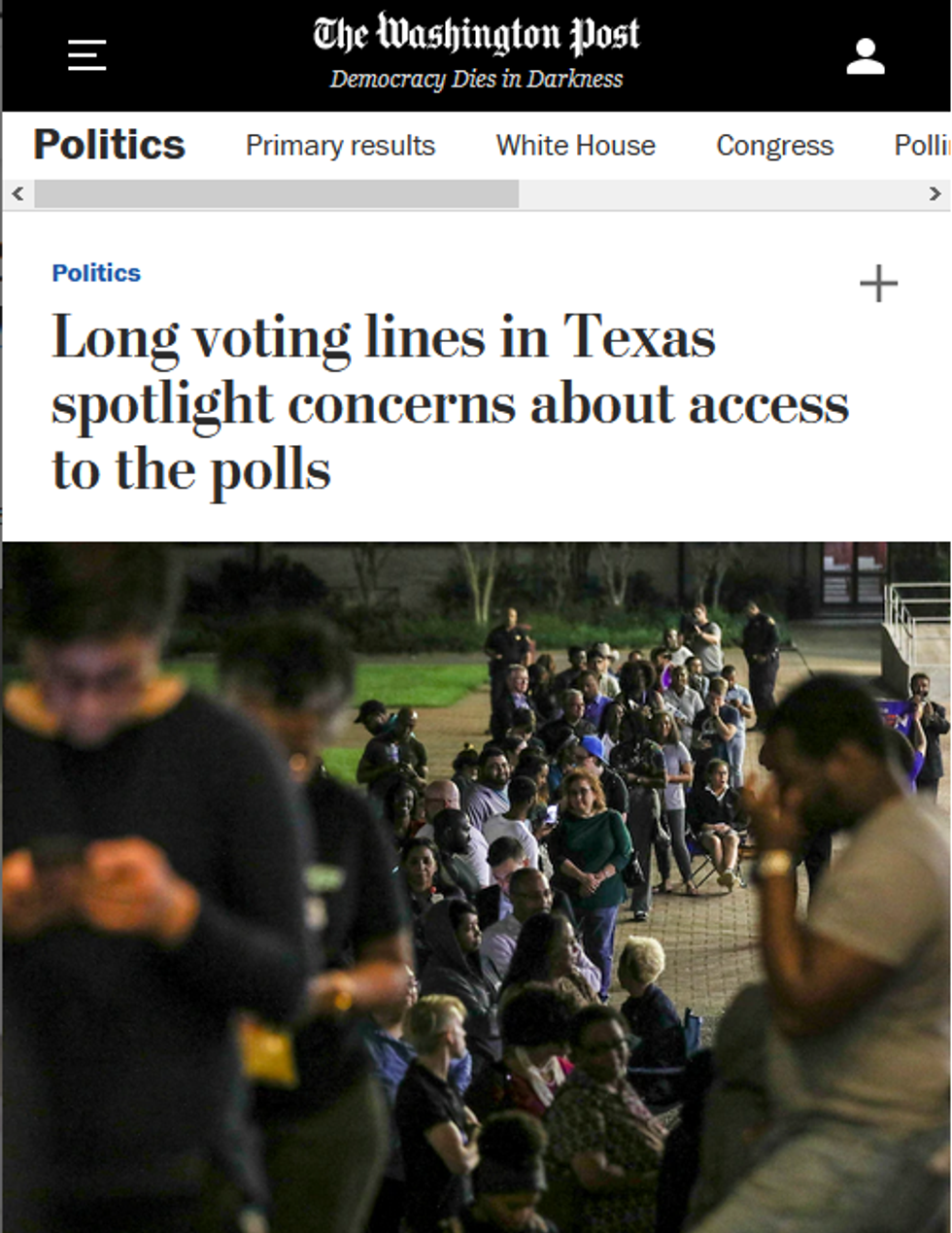

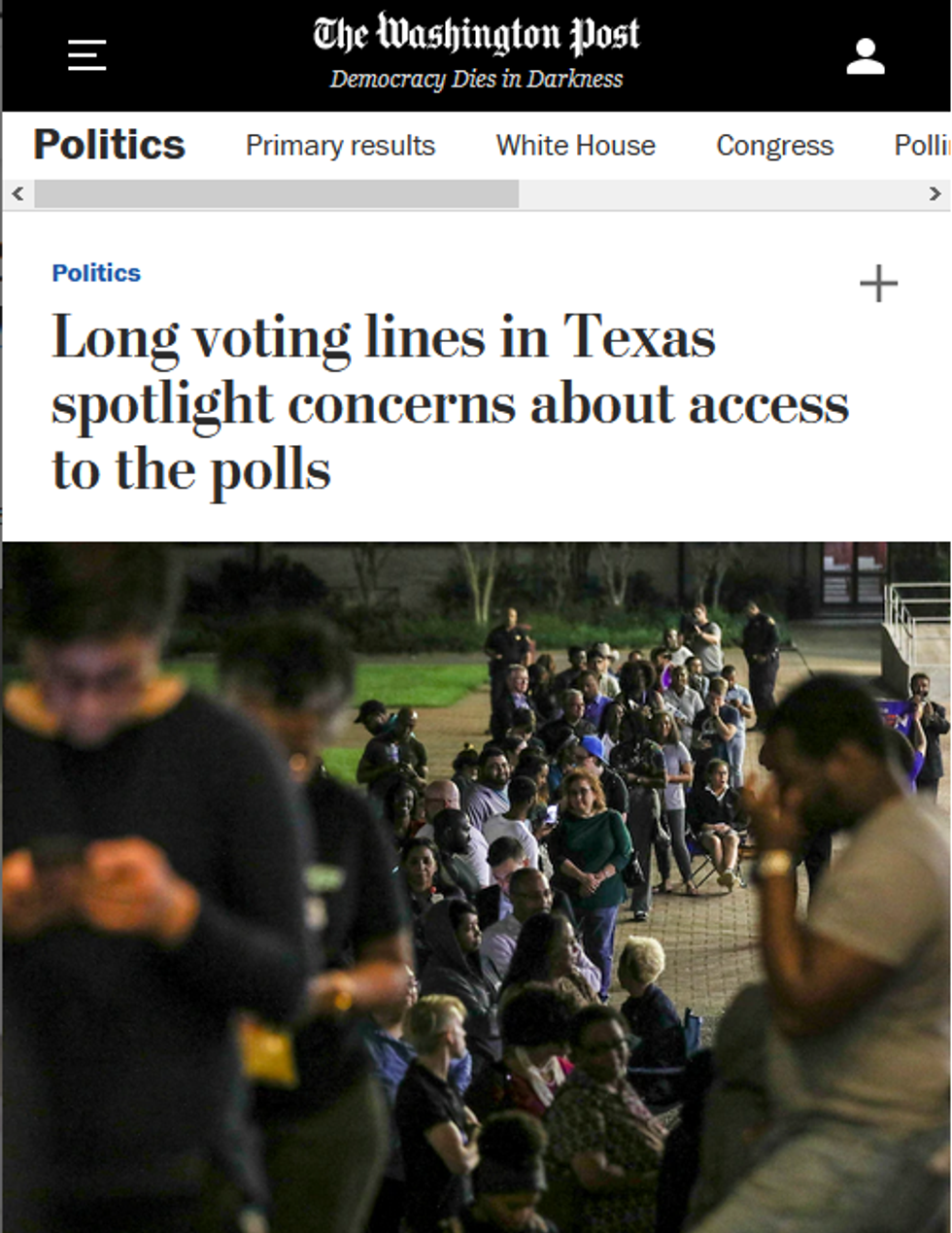

Washington Post photo (3/4/20) of voting lines in Houston on Super Tuesday.

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

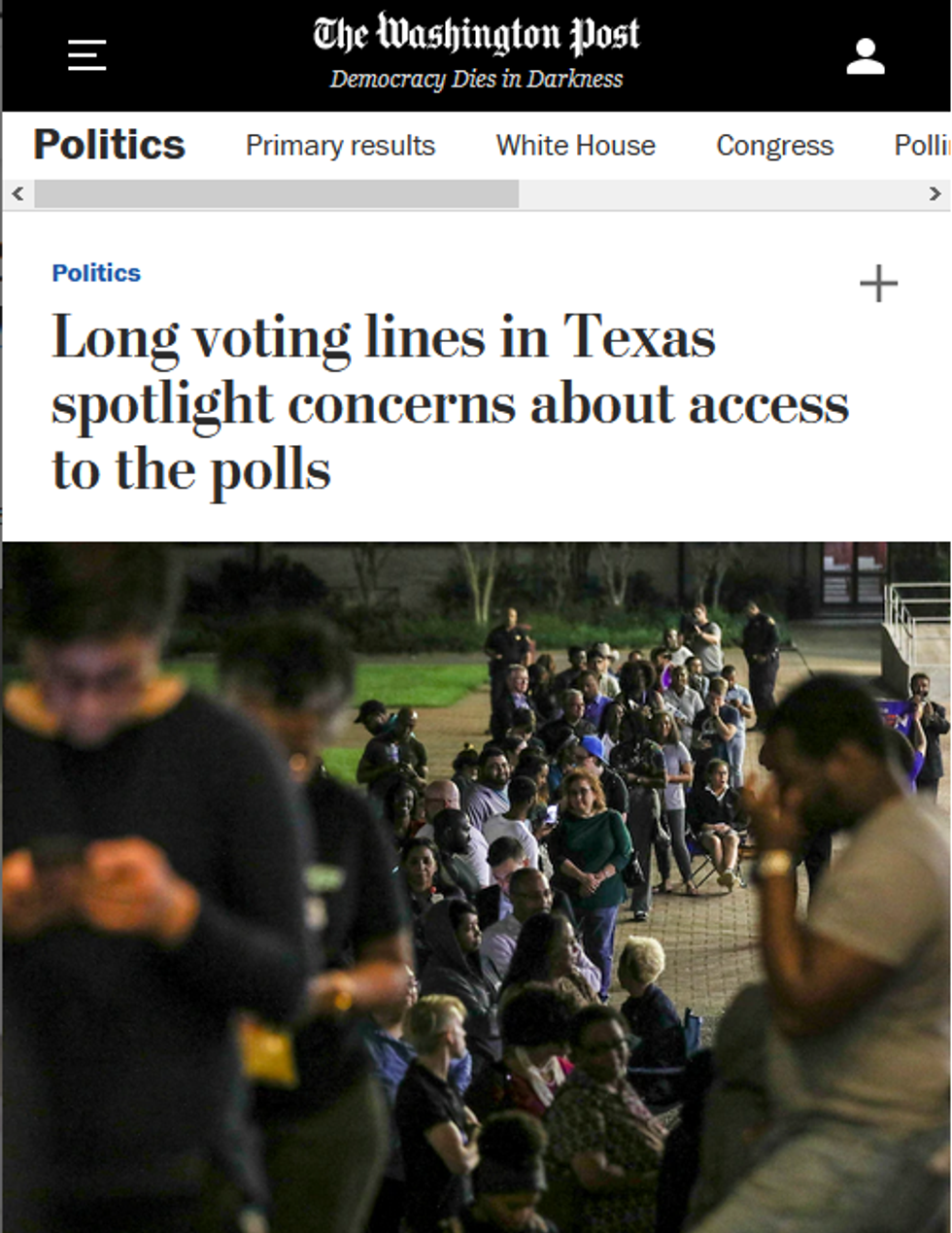

Washington Post photo (3/4/20) of voting lines in Houston on Super Tuesday.

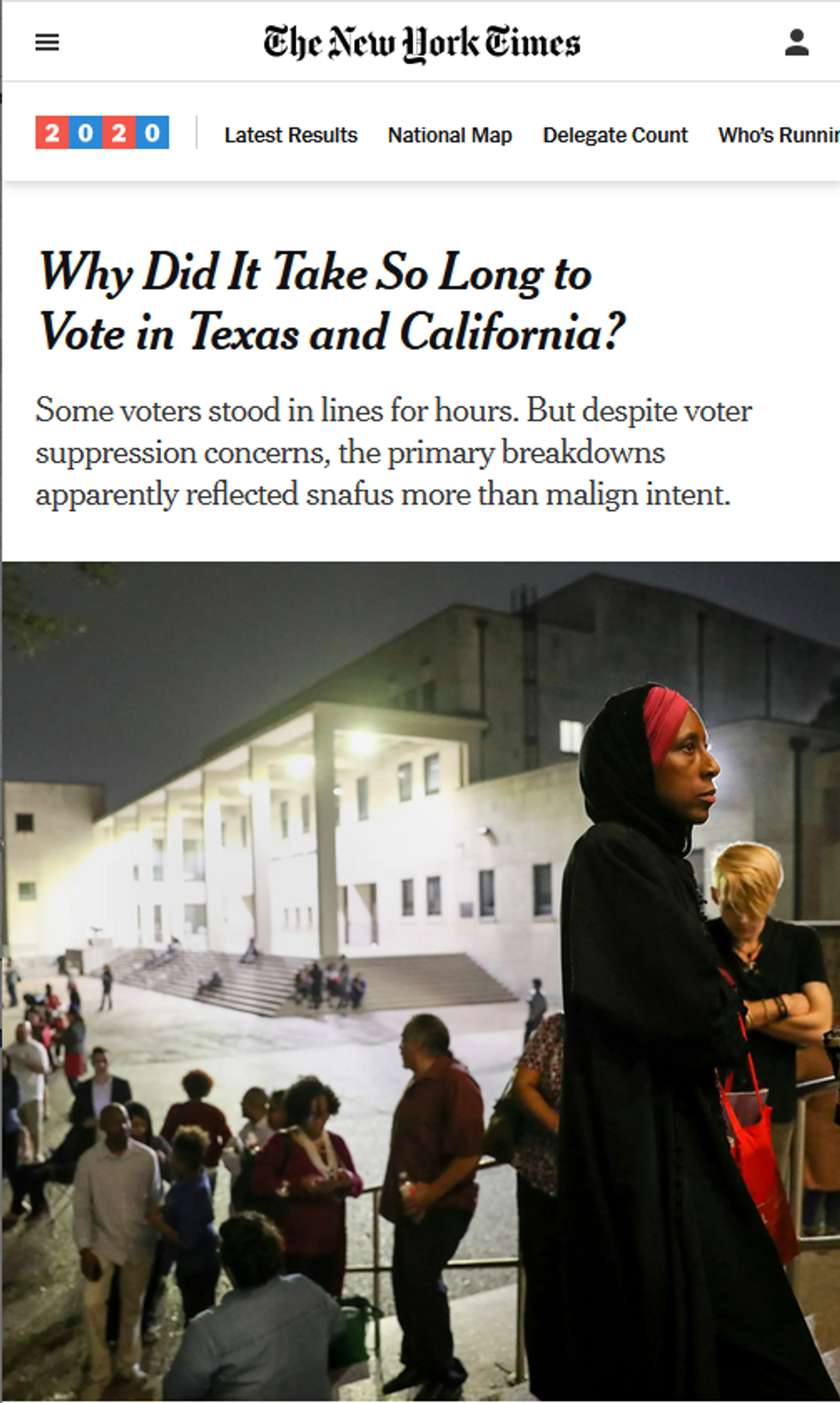

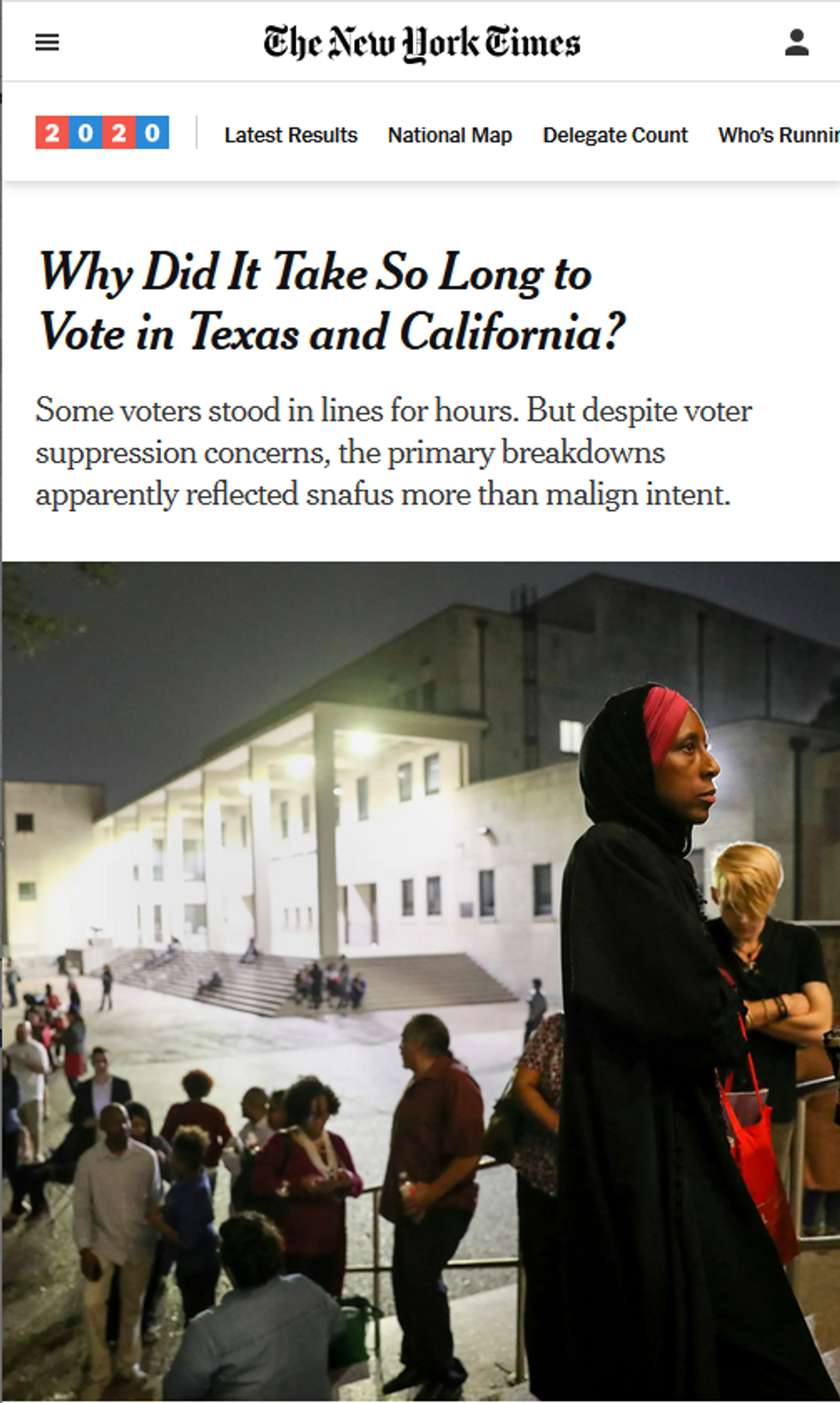

Some voters--disproportionately black and brown ones--waited in line for several hours on Super Tuesday to cast their ballots in the Democratic primary, and media paid attention. But their love for a good visual doesn't always correspond with a love for connecting the dots, and so most of the coverage downplayed any suggestion that there might be voter suppression going on in 2020.

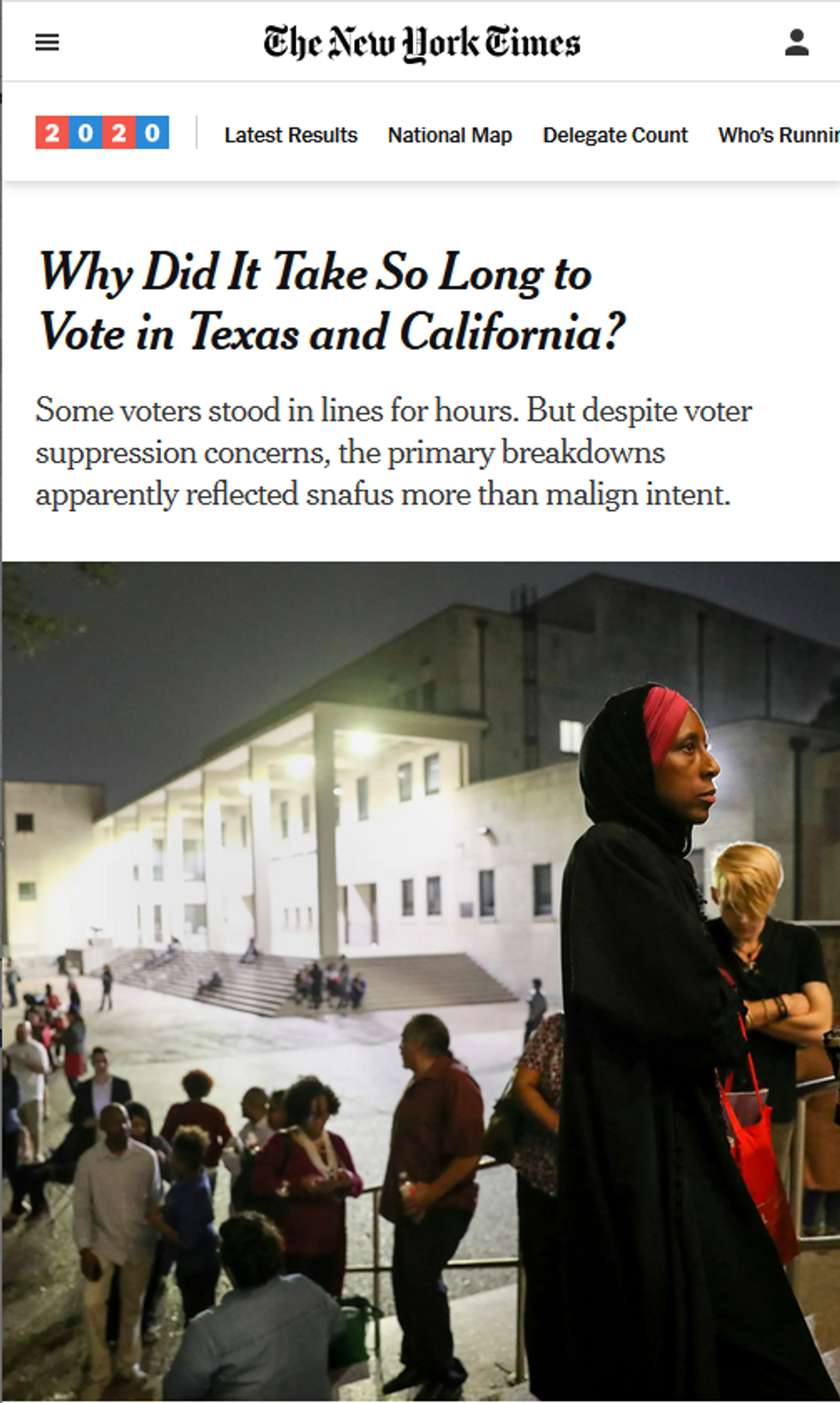

"Why Did It Take So Long to Vote in Texas and California?" asked a New York Times headline (3/4/20), which offered a reassuring answer in its subhead: "Some voters stood in lines for hours. But despite voter suppression concerns, the primary breakdowns apparently reflected snafus more than malign intent." Reporter Michael Wines explained:

Some critics complained on Twitter and elsewhere that the delays amounted to voter suppression in a state where Republicans have been frequently sued, sometimes successfully, for trying to minimize Democratic power. But Texas elections are tightly controlled by local officials, not state ones. And in big cities like Houston and Austin which had the biggest problems on Tuesday, those officials are Democrats with scant reason to depress turnout in Democratic urban strongholds.

And yet, in the very next paragraph, Wines reported that "voting machines were divided equally between Democratic and Republican voters--but many more Democrats turned out to vote on Tuesday," later explaining that

the imbalance stemmed from the county Republican Party's refusal to agree with Democrats to hold a joint primary election in metropolitan Houston in which voters could cast ballots on any machine. All but a handful of the state's 254 counties held joint primaries.

The article's final paragraph noted that the Houston voting site at historically black Texas Southern University, where people waited up to seven hours to vote,

allotted 10 voting machines to each party, and eventually added 14 additional machines for Democratic voters, she said. But of those who showed up on Tuesday, 1,132 voted in the Democratic primary. Sixty-eight voted for Republican candidates.

It's a curiously stark mismatch between evidence and conclusions, a phenomenon repeated in the Washington Post (3/4/20), where reporter Elise Viebeck likewise took issue with those suggesting voter suppression was happening:

One of the remaining Democrats in the presidential field--Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.)--seized on the episode, tweeting that it revealed a "crisis of voter suppression."

However, interviews with election officials, activists and voters pointed to a number of complicated factors that combined to produce the massive lines in Harris County.

(The print version's lead: "Voter suppression came to mind for some, but the reality was complicated.")

Like Wines, Viebeck noted the Harris County GOP's refusal to hold a joint primary, and that, after the Supreme Court's 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision that gutted the Voting Rights Act, Texas closed 750 polling places--more than any other state.

A Houston Chronicle article (3/4/20) about the situation slightly complicated the question of responsibility for giving equal numbers of machines to each party (reporting that though Republicans refused the joint primary, which would have prevented the problem, they were given more machines than they asked for, because the Democratic county clerk's office worried about charges of discrimination), but it also pointed out that "almost two-thirds of the county's voting centers were in county commissioner precincts in west Harris County held by Republicans."

Sure, there were plenty of technological snafus and administrative errors--and those certainly need to be highlighted, so that pressure is put on election officials to fix them--but why pooh-pooh charges of voter suppression when voter suppression (which often masquerades as bureaucratic incompetence) is also an undeniable problem?

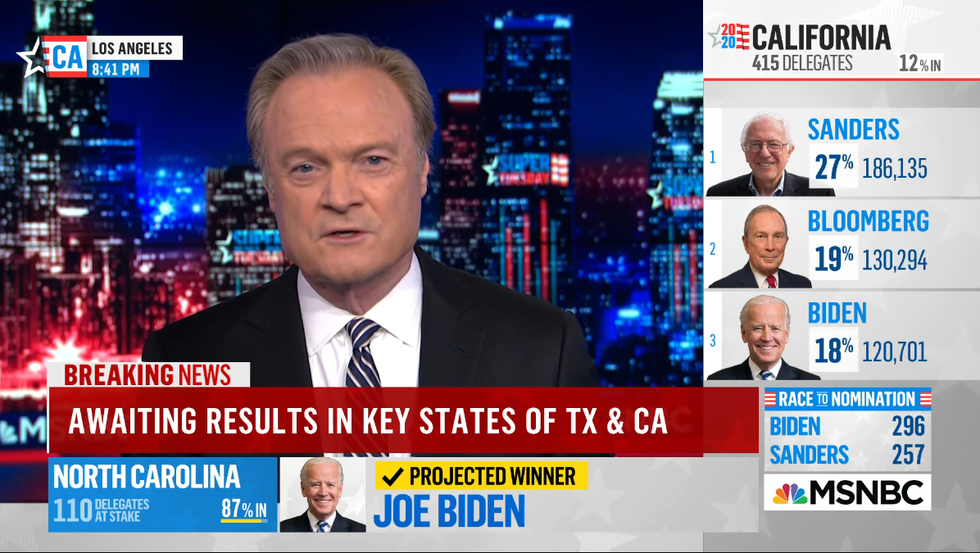

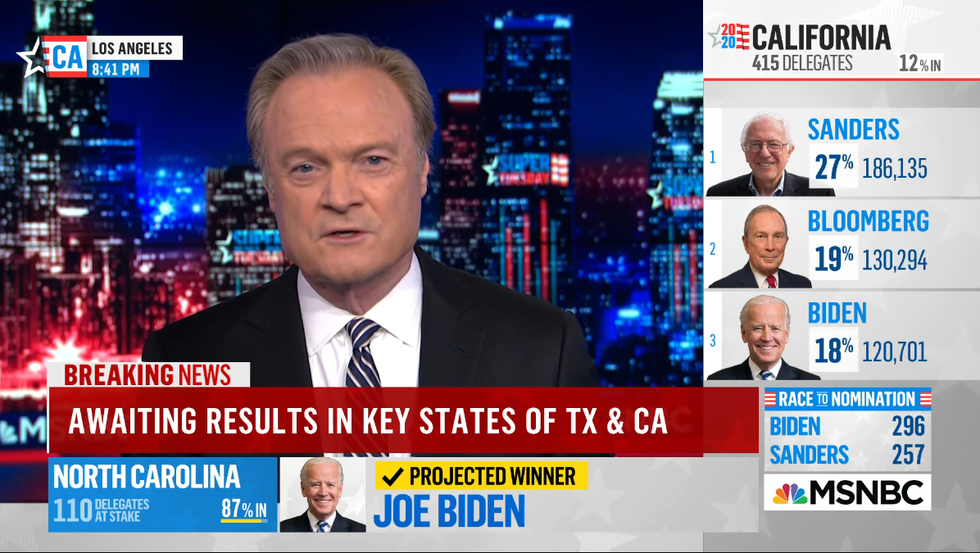

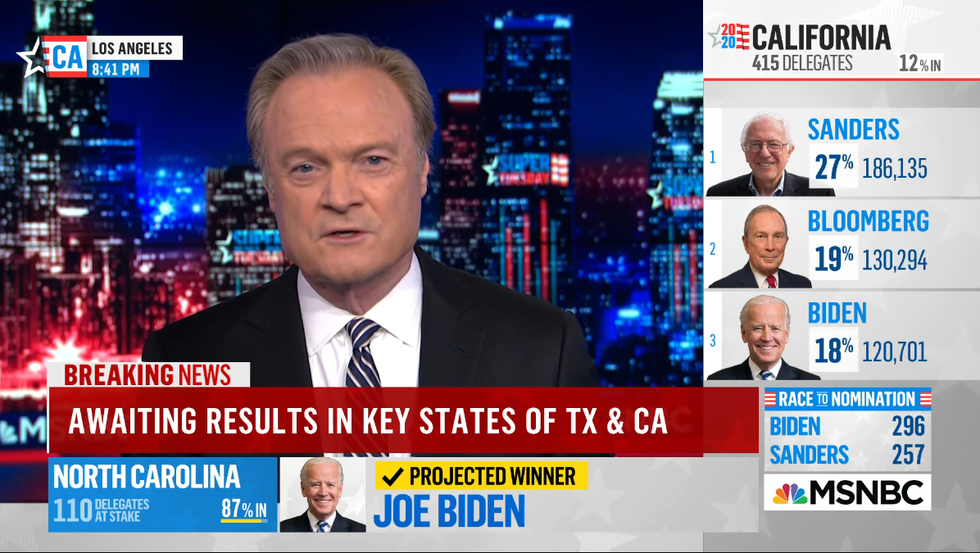

Others went so far as to celebrate the lines. On MSNBC (3/3/20), Lawrence O'Donnell reported:

My phone is filled with texts from people, friends of mine in those lines. I have one from a Hollywood polling place where the casting director is in a conversation with a cinematographer and a math teacher and someone who was an undecided voter an hour ago in that line. And she says they just realized and only just realized that they've been on the line for two hours, because it's been so much fun.... I've got one from a very affluent community in the Pacific Palisades, a director who's been in line for two hours. He's not complaining. They're all kind of excited about this.

It's charitable that the affluent aren't complaining about standing in line for hours (as no one should face obstacles to vote)--but they're also typically not worried about getting fired or missing a paycheck for doing so. Oblivious to this reality, O'Donnell also dismissed the idea that a city should be expected to make it possible for all of its citizens to vote:

And the infrastructure for voting in Los Angeles is a difficult one to maintain. Because on the last mayoral election, this is the election for the mayor of Los Angeles, the voter turnout was 20%. And so to build an infrastructure in Los Angeles that is capable of handling this giant surge turnout that they're getting tonight is impossible.

To be fair, most journalists were more concerned than O'Donnell about people's access to democracy, but they were still remarkably disinterested in asking how the concerted (and partisan) efforts to suppress turnout post-Shelby are playing out in 2020. In the Super Tuesday coverage, NBC (3/4/20) was the only broadcast network to air the words "voter suppression" (in a quote from a voter standing in line in Texas), in a segment less than two minutes long that noted the elimination of many voting centers in both Texas and California, but didn't mention the partisan nature of that act in Texas, instead characterizing it as simply "designed to make voting easier."

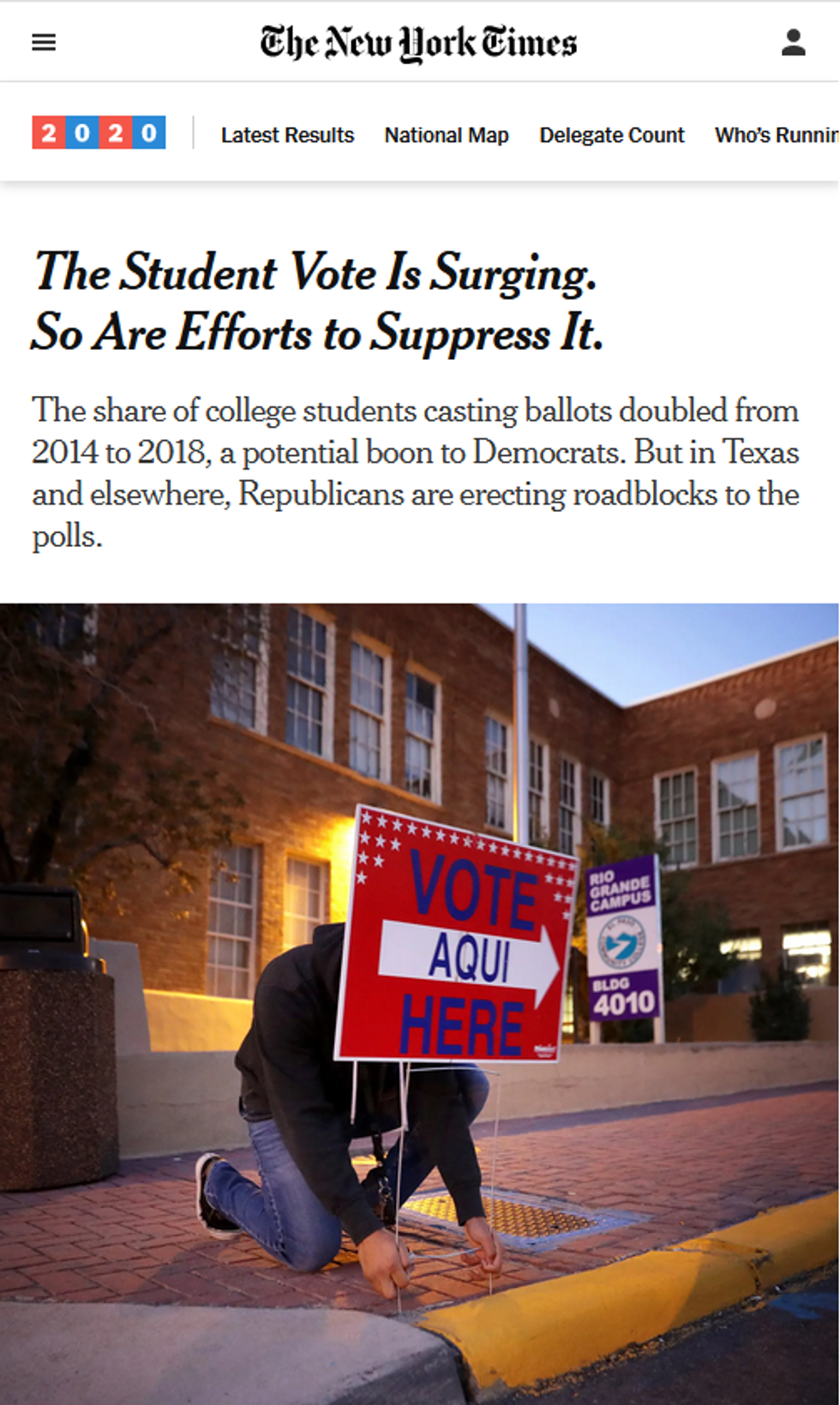

The failure to connect the dots extends to coverage of lower-than-expected turnout, in particular youth turnout. Plenty of reporters seized on early turnout numbers to point out that Bernie Sanders' campaign is failing in its goal of mobilizing youth and other traditionally low-turnout groups, but rarely do they look at the relationship between turnout and suppression--despite the fact that those groups typically face more obstacles to voting.

And Wines' dismissal of suspicions of voter suppression on the grounds that urban polling places are controlled by Democrats seems to willfully ignore the fact that establishment Democrats often have a strong incentive to make sure that older Democrats vote more than young ones--and have been known to manipulate the voting process to their own advantage (City & State, 11/6/18).

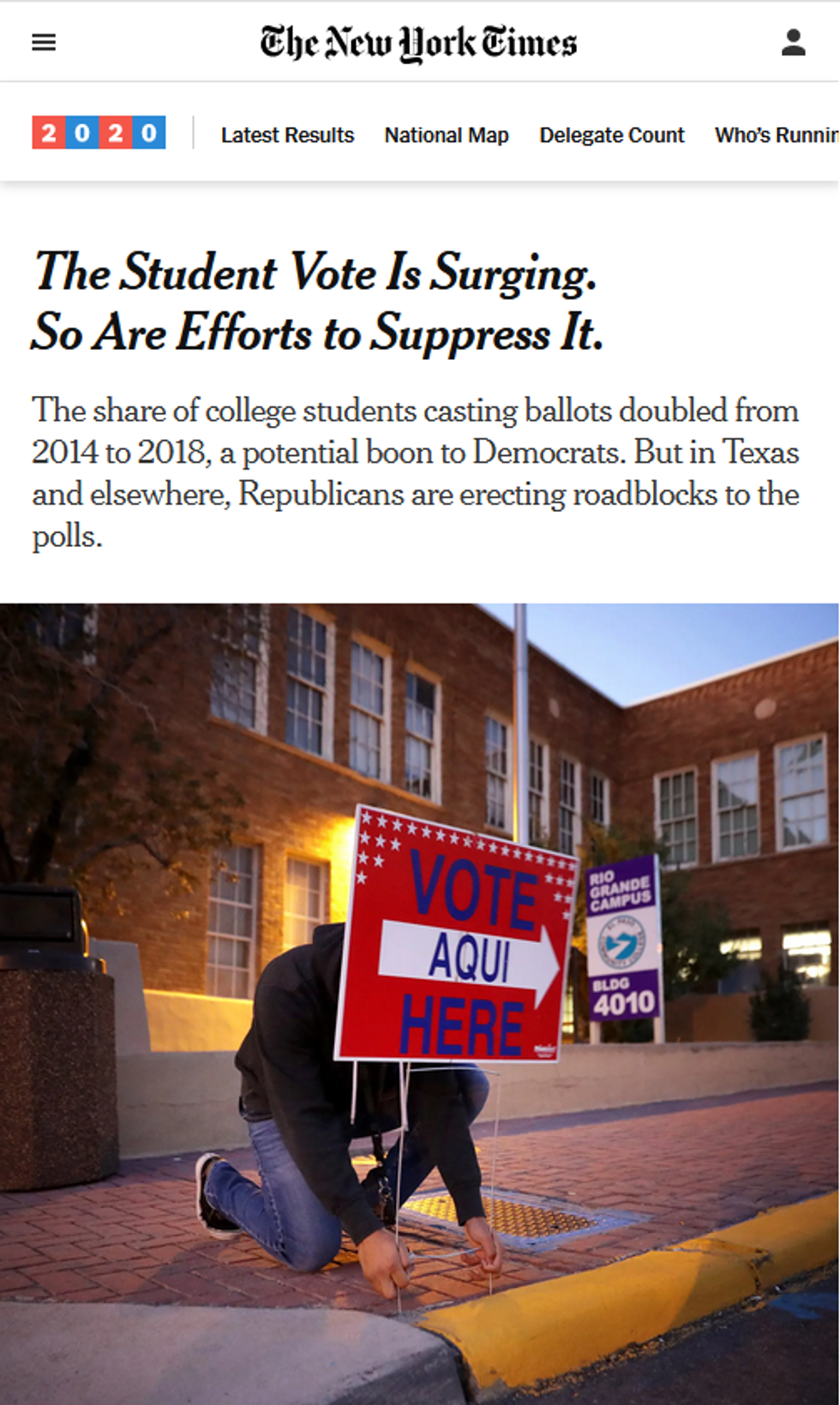

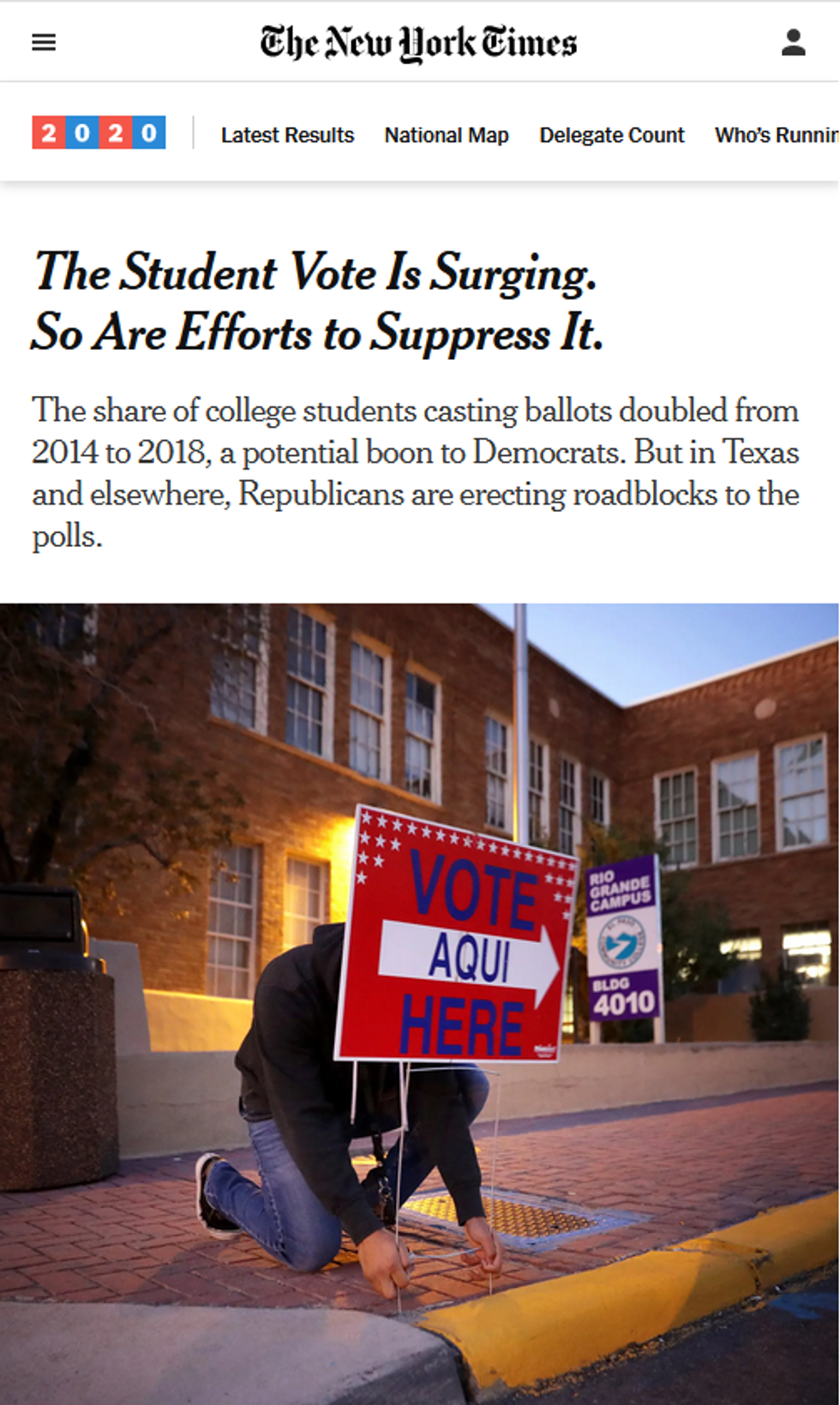

In fact, the Times' coverage was even more remarkable, given Wines' insightful reporting months earlier about efforts to suppress the student vote in Texas and several other states (10/24/19), in which he noted that recently enacted "restrictions fit an increasingly unabashed pattern of Republican politicians' efforts to discourage voters likely to oppose them."

There surely are multiple reasons for lower-than-hoped-for turnout that no doubt intersect with each other, including both obstacles to voting and failure (or lack) of efforts to mobilize voters; it's instructive to see where journalists instinctively turn to look for the culprit. Particularly post-Shelby, ID requirements, poll closures and voter roll purges have ramped up, inevitably taking a toll on democratic access. As Emory University's Carol Anderson recently told Counterspin (3/3/20) about voter suppression:

To see the overall pattern, and continuing to hammer it home, about what is at stake in this democracy...requires good investigative journalism, it requires going beyond the soundbite, it requires a clarion call: This nation is in danger.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Some voters--disproportionately black and brown ones--waited in line for several hours on Super Tuesday to cast their ballots in the Democratic primary, and media paid attention. But their love for a good visual doesn't always correspond with a love for connecting the dots, and so most of the coverage downplayed any suggestion that there might be voter suppression going on in 2020.

"Why Did It Take So Long to Vote in Texas and California?" asked a New York Times headline (3/4/20), which offered a reassuring answer in its subhead: "Some voters stood in lines for hours. But despite voter suppression concerns, the primary breakdowns apparently reflected snafus more than malign intent." Reporter Michael Wines explained:

Some critics complained on Twitter and elsewhere that the delays amounted to voter suppression in a state where Republicans have been frequently sued, sometimes successfully, for trying to minimize Democratic power. But Texas elections are tightly controlled by local officials, not state ones. And in big cities like Houston and Austin which had the biggest problems on Tuesday, those officials are Democrats with scant reason to depress turnout in Democratic urban strongholds.

And yet, in the very next paragraph, Wines reported that "voting machines were divided equally between Democratic and Republican voters--but many more Democrats turned out to vote on Tuesday," later explaining that

the imbalance stemmed from the county Republican Party's refusal to agree with Democrats to hold a joint primary election in metropolitan Houston in which voters could cast ballots on any machine. All but a handful of the state's 254 counties held joint primaries.

The article's final paragraph noted that the Houston voting site at historically black Texas Southern University, where people waited up to seven hours to vote,

allotted 10 voting machines to each party, and eventually added 14 additional machines for Democratic voters, she said. But of those who showed up on Tuesday, 1,132 voted in the Democratic primary. Sixty-eight voted for Republican candidates.

It's a curiously stark mismatch between evidence and conclusions, a phenomenon repeated in the Washington Post (3/4/20), where reporter Elise Viebeck likewise took issue with those suggesting voter suppression was happening:

One of the remaining Democrats in the presidential field--Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.)--seized on the episode, tweeting that it revealed a "crisis of voter suppression."

However, interviews with election officials, activists and voters pointed to a number of complicated factors that combined to produce the massive lines in Harris County.

(The print version's lead: "Voter suppression came to mind for some, but the reality was complicated.")

Like Wines, Viebeck noted the Harris County GOP's refusal to hold a joint primary, and that, after the Supreme Court's 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision that gutted the Voting Rights Act, Texas closed 750 polling places--more than any other state.

A Houston Chronicle article (3/4/20) about the situation slightly complicated the question of responsibility for giving equal numbers of machines to each party (reporting that though Republicans refused the joint primary, which would have prevented the problem, they were given more machines than they asked for, because the Democratic county clerk's office worried about charges of discrimination), but it also pointed out that "almost two-thirds of the county's voting centers were in county commissioner precincts in west Harris County held by Republicans."

Sure, there were plenty of technological snafus and administrative errors--and those certainly need to be highlighted, so that pressure is put on election officials to fix them--but why pooh-pooh charges of voter suppression when voter suppression (which often masquerades as bureaucratic incompetence) is also an undeniable problem?

Others went so far as to celebrate the lines. On MSNBC (3/3/20), Lawrence O'Donnell reported:

My phone is filled with texts from people, friends of mine in those lines. I have one from a Hollywood polling place where the casting director is in a conversation with a cinematographer and a math teacher and someone who was an undecided voter an hour ago in that line. And she says they just realized and only just realized that they've been on the line for two hours, because it's been so much fun.... I've got one from a very affluent community in the Pacific Palisades, a director who's been in line for two hours. He's not complaining. They're all kind of excited about this.

It's charitable that the affluent aren't complaining about standing in line for hours (as no one should face obstacles to vote)--but they're also typically not worried about getting fired or missing a paycheck for doing so. Oblivious to this reality, O'Donnell also dismissed the idea that a city should be expected to make it possible for all of its citizens to vote:

And the infrastructure for voting in Los Angeles is a difficult one to maintain. Because on the last mayoral election, this is the election for the mayor of Los Angeles, the voter turnout was 20%. And so to build an infrastructure in Los Angeles that is capable of handling this giant surge turnout that they're getting tonight is impossible.

To be fair, most journalists were more concerned than O'Donnell about people's access to democracy, but they were still remarkably disinterested in asking how the concerted (and partisan) efforts to suppress turnout post-Shelby are playing out in 2020. In the Super Tuesday coverage, NBC (3/4/20) was the only broadcast network to air the words "voter suppression" (in a quote from a voter standing in line in Texas), in a segment less than two minutes long that noted the elimination of many voting centers in both Texas and California, but didn't mention the partisan nature of that act in Texas, instead characterizing it as simply "designed to make voting easier."

The failure to connect the dots extends to coverage of lower-than-expected turnout, in particular youth turnout. Plenty of reporters seized on early turnout numbers to point out that Bernie Sanders' campaign is failing in its goal of mobilizing youth and other traditionally low-turnout groups, but rarely do they look at the relationship between turnout and suppression--despite the fact that those groups typically face more obstacles to voting.

And Wines' dismissal of suspicions of voter suppression on the grounds that urban polling places are controlled by Democrats seems to willfully ignore the fact that establishment Democrats often have a strong incentive to make sure that older Democrats vote more than young ones--and have been known to manipulate the voting process to their own advantage (City & State, 11/6/18).

In fact, the Times' coverage was even more remarkable, given Wines' insightful reporting months earlier about efforts to suppress the student vote in Texas and several other states (10/24/19), in which he noted that recently enacted "restrictions fit an increasingly unabashed pattern of Republican politicians' efforts to discourage voters likely to oppose them."

There surely are multiple reasons for lower-than-hoped-for turnout that no doubt intersect with each other, including both obstacles to voting and failure (or lack) of efforts to mobilize voters; it's instructive to see where journalists instinctively turn to look for the culprit. Particularly post-Shelby, ID requirements, poll closures and voter roll purges have ramped up, inevitably taking a toll on democratic access. As Emory University's Carol Anderson recently told Counterspin (3/3/20) about voter suppression:

To see the overall pattern, and continuing to hammer it home, about what is at stake in this democracy...requires good investigative journalism, it requires going beyond the soundbite, it requires a clarion call: This nation is in danger.

Some voters--disproportionately black and brown ones--waited in line for several hours on Super Tuesday to cast their ballots in the Democratic primary, and media paid attention. But their love for a good visual doesn't always correspond with a love for connecting the dots, and so most of the coverage downplayed any suggestion that there might be voter suppression going on in 2020.

"Why Did It Take So Long to Vote in Texas and California?" asked a New York Times headline (3/4/20), which offered a reassuring answer in its subhead: "Some voters stood in lines for hours. But despite voter suppression concerns, the primary breakdowns apparently reflected snafus more than malign intent." Reporter Michael Wines explained:

Some critics complained on Twitter and elsewhere that the delays amounted to voter suppression in a state where Republicans have been frequently sued, sometimes successfully, for trying to minimize Democratic power. But Texas elections are tightly controlled by local officials, not state ones. And in big cities like Houston and Austin which had the biggest problems on Tuesday, those officials are Democrats with scant reason to depress turnout in Democratic urban strongholds.

And yet, in the very next paragraph, Wines reported that "voting machines were divided equally between Democratic and Republican voters--but many more Democrats turned out to vote on Tuesday," later explaining that

the imbalance stemmed from the county Republican Party's refusal to agree with Democrats to hold a joint primary election in metropolitan Houston in which voters could cast ballots on any machine. All but a handful of the state's 254 counties held joint primaries.

The article's final paragraph noted that the Houston voting site at historically black Texas Southern University, where people waited up to seven hours to vote,

allotted 10 voting machines to each party, and eventually added 14 additional machines for Democratic voters, she said. But of those who showed up on Tuesday, 1,132 voted in the Democratic primary. Sixty-eight voted for Republican candidates.

It's a curiously stark mismatch between evidence and conclusions, a phenomenon repeated in the Washington Post (3/4/20), where reporter Elise Viebeck likewise took issue with those suggesting voter suppression was happening:

One of the remaining Democrats in the presidential field--Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.)--seized on the episode, tweeting that it revealed a "crisis of voter suppression."

However, interviews with election officials, activists and voters pointed to a number of complicated factors that combined to produce the massive lines in Harris County.

(The print version's lead: "Voter suppression came to mind for some, but the reality was complicated.")

Like Wines, Viebeck noted the Harris County GOP's refusal to hold a joint primary, and that, after the Supreme Court's 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision that gutted the Voting Rights Act, Texas closed 750 polling places--more than any other state.

A Houston Chronicle article (3/4/20) about the situation slightly complicated the question of responsibility for giving equal numbers of machines to each party (reporting that though Republicans refused the joint primary, which would have prevented the problem, they were given more machines than they asked for, because the Democratic county clerk's office worried about charges of discrimination), but it also pointed out that "almost two-thirds of the county's voting centers were in county commissioner precincts in west Harris County held by Republicans."

Sure, there were plenty of technological snafus and administrative errors--and those certainly need to be highlighted, so that pressure is put on election officials to fix them--but why pooh-pooh charges of voter suppression when voter suppression (which often masquerades as bureaucratic incompetence) is also an undeniable problem?

Others went so far as to celebrate the lines. On MSNBC (3/3/20), Lawrence O'Donnell reported:

My phone is filled with texts from people, friends of mine in those lines. I have one from a Hollywood polling place where the casting director is in a conversation with a cinematographer and a math teacher and someone who was an undecided voter an hour ago in that line. And she says they just realized and only just realized that they've been on the line for two hours, because it's been so much fun.... I've got one from a very affluent community in the Pacific Palisades, a director who's been in line for two hours. He's not complaining. They're all kind of excited about this.

It's charitable that the affluent aren't complaining about standing in line for hours (as no one should face obstacles to vote)--but they're also typically not worried about getting fired or missing a paycheck for doing so. Oblivious to this reality, O'Donnell also dismissed the idea that a city should be expected to make it possible for all of its citizens to vote:

And the infrastructure for voting in Los Angeles is a difficult one to maintain. Because on the last mayoral election, this is the election for the mayor of Los Angeles, the voter turnout was 20%. And so to build an infrastructure in Los Angeles that is capable of handling this giant surge turnout that they're getting tonight is impossible.

To be fair, most journalists were more concerned than O'Donnell about people's access to democracy, but they were still remarkably disinterested in asking how the concerted (and partisan) efforts to suppress turnout post-Shelby are playing out in 2020. In the Super Tuesday coverage, NBC (3/4/20) was the only broadcast network to air the words "voter suppression" (in a quote from a voter standing in line in Texas), in a segment less than two minutes long that noted the elimination of many voting centers in both Texas and California, but didn't mention the partisan nature of that act in Texas, instead characterizing it as simply "designed to make voting easier."

The failure to connect the dots extends to coverage of lower-than-expected turnout, in particular youth turnout. Plenty of reporters seized on early turnout numbers to point out that Bernie Sanders' campaign is failing in its goal of mobilizing youth and other traditionally low-turnout groups, but rarely do they look at the relationship between turnout and suppression--despite the fact that those groups typically face more obstacles to voting.

And Wines' dismissal of suspicions of voter suppression on the grounds that urban polling places are controlled by Democrats seems to willfully ignore the fact that establishment Democrats often have a strong incentive to make sure that older Democrats vote more than young ones--and have been known to manipulate the voting process to their own advantage (City & State, 11/6/18).

In fact, the Times' coverage was even more remarkable, given Wines' insightful reporting months earlier about efforts to suppress the student vote in Texas and several other states (10/24/19), in which he noted that recently enacted "restrictions fit an increasingly unabashed pattern of Republican politicians' efforts to discourage voters likely to oppose them."

There surely are multiple reasons for lower-than-hoped-for turnout that no doubt intersect with each other, including both obstacles to voting and failure (or lack) of efforts to mobilize voters; it's instructive to see where journalists instinctively turn to look for the culprit. Particularly post-Shelby, ID requirements, poll closures and voter roll purges have ramped up, inevitably taking a toll on democratic access. As Emory University's Carol Anderson recently told Counterspin (3/3/20) about voter suppression:

To see the overall pattern, and continuing to hammer it home, about what is at stake in this democracy...requires good investigative journalism, it requires going beyond the soundbite, it requires a clarion call: This nation is in danger.