SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Canada once had a publicly owned pharmaceutical company that could have made a difference in the current coronavirus crisis -- except that we sold it.

Connaught Labs was a superstar in global medicine. For seven decades, this publicly owned Canadian company performed brilliantly on the national and international stage, contributing to medical breakthroughs and developing affordable treatments and vaccines for deadly diseases.

Hated by its corporate competitors, Connaught was unique among pharmaceutical companies in that its focus was on human need, not profit.

Canada once had a publicly owned pharmaceutical company that could have made a difference in the current coronavirus crisis -- except that we sold it.

Connaught Labs was a superstar in global medicine. For seven decades, this publicly owned Canadian company performed brilliantly on the national and international stage, contributing to medical breakthroughs and developing affordable treatments and vaccines for deadly diseases.

Hated by its corporate competitors, Connaught was unique among pharmaceutical companies in that its focus was on human need, not profit.

It would have come in handy today.

In fact, Connaught got its start amid a diphtheria outbreak in 1913. Toronto doctor John Gerald FitzGerald was outraged that children were dying in large numbers even though there was a diphtheria treatment available from a U.S. manufacturer. But, at $25 a dose, it was unaffordable to all but the rich. FitzGerald set out to change that -- and did.

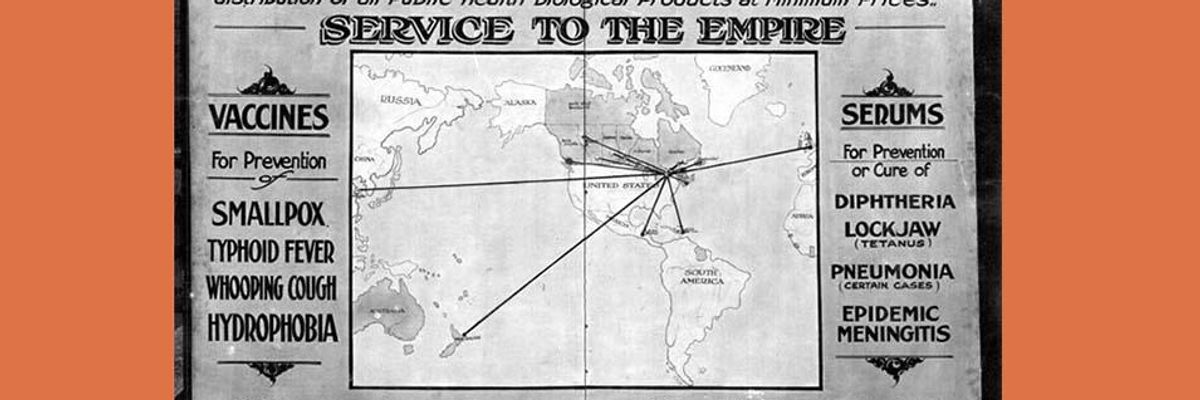

After experimenting on a horse in a downtown Toronto stable, FitzGerald developed an antitoxin that proved effective in treating diphtheria, and made it available to public health outlets across the country. Then, with lab space provided by the University of Toronto, he and his team went on to produce low-cost treatments and vaccines for other common killers, including tetanus, typhoid and meningitis.

Connaught developed an impressive research capacity, with its scientists contributing to some of the biggest medical breakthroughs of the 20th century -- including penicillin and the Salk and Sabin polio vaccines. It also played a central role in the global eradication of smallpox.

"It was a pioneer in a lot of ways," says Colleen Fuller, a research associate of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. "It did things commercial companies wouldn't do because they weren't willing to take the financial risks."

Fuller argues that if a publicly owned Connaught were still operating today, it could be contributing to the development of the coronavirus vaccine -- and ensuring a Canadian supply if there was a global shortage.

Yet, tragically it isn't.

Succumbing to corporate pressure and a misguided belief that the private sector always does things better, Brian Mulroney's Progressive Conservative government privatized Connaught Labs in the 1980s. Today, what remains of this once-dazzling Canadian public enterprise has been taken over by a giant French pharmaceutical company.

The coronavirus outbreak may finally help expose the fallacy of the notion that the private marketplace is innately superior -- which has been the guiding principle in Anglo-American countries (including Canada) for the past four decades, leading to the constant denigration of government and its functions.

Fortunately, Canada's public health care system, established in the 1960s, has been so popular that it has survived, despite attacks of "socialized medicine" -- although our political leaders have quietly whittled away funding for the system in recent decades.

If the foolishness of cutting funding for public health care wasn't already abundantly clear, the coronavirus has driven it home with a sledgehammer -- as we've witnessed the extra struggles the U.S. faces in containing the virus with its lack of public health care.

Still, our willingness to go along with the privatization cult in recent decades has left us weaker and less protected than we could be.

Not only do we no longer have Connaught Labs, but Canada spends $1 billion a year funding basic medical research at Canadian universities, yet relies on the private marketplace to produce, control -- and profit from -- the resulting medical innovations.

For instance, the crucial work in developing a vaccine to treat Ebola was done by Canadian scientists at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg -- and financed by Canadian taxpayer money. But sole licensing rights to the vaccine were granted to a small U.S. company, which then sublicensed it to pharmaceutical giant Merck for $50 million.

Although Merck is now producing the vaccine, critics have charged that the company did "next to nothing" to rush the vaccine into production during the deadly Ebola outbreak in West Africa, according to a recent paper published in the Journal of Law and Biosciences.

With a surge in future global pandemics expected, it might well be time to rethink Canada's foolhardy attachment to the notion "the private sector always does things better."

Always unproven, that theory is looking increasingly far-fetched.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Canada once had a publicly owned pharmaceutical company that could have made a difference in the current coronavirus crisis -- except that we sold it.

Connaught Labs was a superstar in global medicine. For seven decades, this publicly owned Canadian company performed brilliantly on the national and international stage, contributing to medical breakthroughs and developing affordable treatments and vaccines for deadly diseases.

Hated by its corporate competitors, Connaught was unique among pharmaceutical companies in that its focus was on human need, not profit.

It would have come in handy today.

In fact, Connaught got its start amid a diphtheria outbreak in 1913. Toronto doctor John Gerald FitzGerald was outraged that children were dying in large numbers even though there was a diphtheria treatment available from a U.S. manufacturer. But, at $25 a dose, it was unaffordable to all but the rich. FitzGerald set out to change that -- and did.

After experimenting on a horse in a downtown Toronto stable, FitzGerald developed an antitoxin that proved effective in treating diphtheria, and made it available to public health outlets across the country. Then, with lab space provided by the University of Toronto, he and his team went on to produce low-cost treatments and vaccines for other common killers, including tetanus, typhoid and meningitis.

Connaught developed an impressive research capacity, with its scientists contributing to some of the biggest medical breakthroughs of the 20th century -- including penicillin and the Salk and Sabin polio vaccines. It also played a central role in the global eradication of smallpox.

"It was a pioneer in a lot of ways," says Colleen Fuller, a research associate of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. "It did things commercial companies wouldn't do because they weren't willing to take the financial risks."

Fuller argues that if a publicly owned Connaught were still operating today, it could be contributing to the development of the coronavirus vaccine -- and ensuring a Canadian supply if there was a global shortage.

Yet, tragically it isn't.

Succumbing to corporate pressure and a misguided belief that the private sector always does things better, Brian Mulroney's Progressive Conservative government privatized Connaught Labs in the 1980s. Today, what remains of this once-dazzling Canadian public enterprise has been taken over by a giant French pharmaceutical company.

The coronavirus outbreak may finally help expose the fallacy of the notion that the private marketplace is innately superior -- which has been the guiding principle in Anglo-American countries (including Canada) for the past four decades, leading to the constant denigration of government and its functions.

Fortunately, Canada's public health care system, established in the 1960s, has been so popular that it has survived, despite attacks of "socialized medicine" -- although our political leaders have quietly whittled away funding for the system in recent decades.

If the foolishness of cutting funding for public health care wasn't already abundantly clear, the coronavirus has driven it home with a sledgehammer -- as we've witnessed the extra struggles the U.S. faces in containing the virus with its lack of public health care.

Still, our willingness to go along with the privatization cult in recent decades has left us weaker and less protected than we could be.

Not only do we no longer have Connaught Labs, but Canada spends $1 billion a year funding basic medical research at Canadian universities, yet relies on the private marketplace to produce, control -- and profit from -- the resulting medical innovations.

For instance, the crucial work in developing a vaccine to treat Ebola was done by Canadian scientists at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg -- and financed by Canadian taxpayer money. But sole licensing rights to the vaccine were granted to a small U.S. company, which then sublicensed it to pharmaceutical giant Merck for $50 million.

Although Merck is now producing the vaccine, critics have charged that the company did "next to nothing" to rush the vaccine into production during the deadly Ebola outbreak in West Africa, according to a recent paper published in the Journal of Law and Biosciences.

With a surge in future global pandemics expected, it might well be time to rethink Canada's foolhardy attachment to the notion "the private sector always does things better."

Always unproven, that theory is looking increasingly far-fetched.

Canada once had a publicly owned pharmaceutical company that could have made a difference in the current coronavirus crisis -- except that we sold it.

Connaught Labs was a superstar in global medicine. For seven decades, this publicly owned Canadian company performed brilliantly on the national and international stage, contributing to medical breakthroughs and developing affordable treatments and vaccines for deadly diseases.

Hated by its corporate competitors, Connaught was unique among pharmaceutical companies in that its focus was on human need, not profit.

It would have come in handy today.

In fact, Connaught got its start amid a diphtheria outbreak in 1913. Toronto doctor John Gerald FitzGerald was outraged that children were dying in large numbers even though there was a diphtheria treatment available from a U.S. manufacturer. But, at $25 a dose, it was unaffordable to all but the rich. FitzGerald set out to change that -- and did.

After experimenting on a horse in a downtown Toronto stable, FitzGerald developed an antitoxin that proved effective in treating diphtheria, and made it available to public health outlets across the country. Then, with lab space provided by the University of Toronto, he and his team went on to produce low-cost treatments and vaccines for other common killers, including tetanus, typhoid and meningitis.

Connaught developed an impressive research capacity, with its scientists contributing to some of the biggest medical breakthroughs of the 20th century -- including penicillin and the Salk and Sabin polio vaccines. It also played a central role in the global eradication of smallpox.

"It was a pioneer in a lot of ways," says Colleen Fuller, a research associate of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. "It did things commercial companies wouldn't do because they weren't willing to take the financial risks."

Fuller argues that if a publicly owned Connaught were still operating today, it could be contributing to the development of the coronavirus vaccine -- and ensuring a Canadian supply if there was a global shortage.

Yet, tragically it isn't.

Succumbing to corporate pressure and a misguided belief that the private sector always does things better, Brian Mulroney's Progressive Conservative government privatized Connaught Labs in the 1980s. Today, what remains of this once-dazzling Canadian public enterprise has been taken over by a giant French pharmaceutical company.

The coronavirus outbreak may finally help expose the fallacy of the notion that the private marketplace is innately superior -- which has been the guiding principle in Anglo-American countries (including Canada) for the past four decades, leading to the constant denigration of government and its functions.

Fortunately, Canada's public health care system, established in the 1960s, has been so popular that it has survived, despite attacks of "socialized medicine" -- although our political leaders have quietly whittled away funding for the system in recent decades.

If the foolishness of cutting funding for public health care wasn't already abundantly clear, the coronavirus has driven it home with a sledgehammer -- as we've witnessed the extra struggles the U.S. faces in containing the virus with its lack of public health care.

Still, our willingness to go along with the privatization cult in recent decades has left us weaker and less protected than we could be.

Not only do we no longer have Connaught Labs, but Canada spends $1 billion a year funding basic medical research at Canadian universities, yet relies on the private marketplace to produce, control -- and profit from -- the resulting medical innovations.

For instance, the crucial work in developing a vaccine to treat Ebola was done by Canadian scientists at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg -- and financed by Canadian taxpayer money. But sole licensing rights to the vaccine were granted to a small U.S. company, which then sublicensed it to pharmaceutical giant Merck for $50 million.

Although Merck is now producing the vaccine, critics have charged that the company did "next to nothing" to rush the vaccine into production during the deadly Ebola outbreak in West Africa, according to a recent paper published in the Journal of Law and Biosciences.

With a surge in future global pandemics expected, it might well be time to rethink Canada's foolhardy attachment to the notion "the private sector always does things better."

Always unproven, that theory is looking increasingly far-fetched.