Sanders is absolutely right that the current public-health crisis, and its economic aftershocks, expose the great vulnerability of our unequal, increasingly unjust society. (Photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

The Democrats' Coronavirus Divide

Sanders is right about the need for radical change; Biden offers a woman VP and a return to ‘normalcy.’

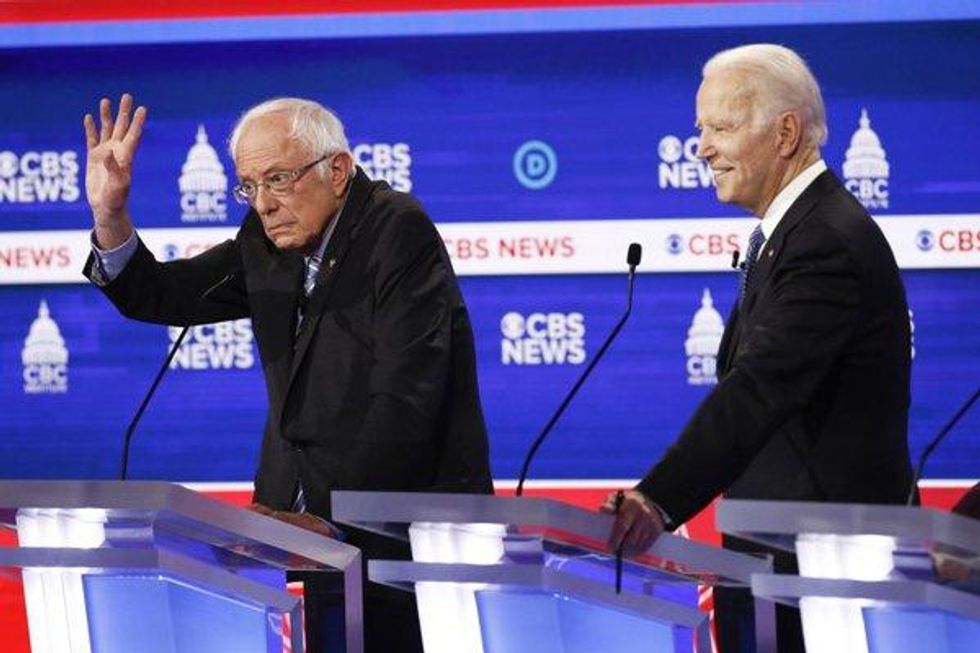

Last night's Democratic candidate debate, held amid the coronavirus crisis in a nearly empty CNN studio in Washington, D.C., provided voters with what might be their final chance to see, in stark relief, the choice between the two remaining contenders for the Democratic nomination: Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders.

With Biden on a path to wrap up the most delegates after the last round of primaries, the campaigns seemed to be inching toward some sort of detente, with Sanders acknowledging Biden as the likely nominee, and Biden adopting some progressive policy positions, recognizing Sanders's leadership of a movement that is necessary to a Democratic victory.

The coronavirus pandemic exposes the huge cracks in our society that Sanders has been pointing out all along.

Would the two candidates begin to form a coherent, unified position for addressing the pandemic and ending the disastrous presidency of Donald Trump?

Nope.

Instead, we got two hours of heated, personal exchanges, rehashing of old votes, ("yes you did," "no I didn't"), a truly reprehensible round of red-baiting of Sanders, and an ideological collision over radical change versus incrementalism that was never adequately worked out.

Biden did commit to choosing a woman as a running mate, which is big news. It also suggests that he might be getting ready to pick Elizabeth Warren, whose policy positions he has been adopting lately--an olive branch to the progressive party base.

But when Biden and Sanders left the debate stage they were a long way from coming together.

Sanders is absolutely right that the current public-health crisis, and its economic aftershocks, expose the great vulnerability of our unequal, increasingly unjust society.

As he repeatedly pointed out, "We are the only major nation on Earth without guaranteed health care." We spend twice as much per capita on health care than other developed countries, but our patchwork of private insurance and the millions of Amercians who can't afford to see a doctor leave us woefully unprepared to launch an effective, coordinated response to this pandemic.

Add to that the desperate situation of workers who can't take paid sick leave, and the majority of Americans living paycheck to paycheck who can't ride out the sudden closure of their workplaces, and you have a powerful argument for Sanders's basic arguments for Medicare for All, increasing the minimum wage, taxing the rich and corporations, and restoring the social safety net.

The coronavirus pandemic exposes the huge cracks in our society that Sanders has been pointing out all along.

Biden's response was to say the nation is in the throes of "a national emergency" that "has nothing to do with Bernie's Medicare for All."

The heart of the Biden argument--and what has persuaded voters from Michigan to Mississippi--is that the Sanders revolution is unrealistic. Sanders has the moral high ground. Biden doesn't dispute it. But getting to Medicare for All would take years, he said, and people need action right now.

If Biden says coronavirus is an emergency requiring a response akin to war, Sanders said, "I look at climate change in the exact same way."

Biden's related argument is that he knows how to get things done--from diplomacy with foreign leaders to figuring out how to get a bill through a divided Congress.

I suspect Biden, like many viewers, thought Sanders might be ready to concede the point. It seemed possible that Sanders might want to lecture Biden on the right thing to do, and then Biden, as he has been doing in recent days, would jovially agree that Sanders has some great ideas and begin to co-opt them and make them his own. That's how the primary process ordinarily works.

But these are not ordinary times. And Sanders is not an ordinary politician.

Instead, Sanders dredged up Biden's history--supporting the bank bailout; his floor speeches supporting the budget-balancing Bowles-Simpson Act, which included cuts to Social Security and Medicare; his contributions from the pharmaceutical industry; his votes for the Iraq War and the Defense of Marriage Act (both of which he has since acknowledged were mistakes); and his multiple votes for the anti-abortion Hyde Amendment barring the use of federal funds for abortion.

Biden, helped along by the moderators, got his revenge by attacking Sanders for his long-ago praise of literacy rates in Cuba and in Nicaragua under the Sandinistas, and spuriously suggesting that Sanders might coddle the authoritarian government of China. It was transparent red-baiting and just plain ugly.

In several instances, Sanders seemed unwilling to take yes for an answer. Biden has adopted Senator Elizabeth Warren's bankruptcy bill and part of Sanders's free-college plan that would cover tuition at public universities for families that earn less than $125,000 per year.

But the bankruptcy bill Warren seeks to undo is one Biden helped to write, Sanders pointed out.

"I did not!" Biden huffed.

Sanders had plenty of material. Biden, as a Senator from Delaware, spent years developing a cozy relationship with the banking industry headquartered there. He has a long record of less-than-perfect populism.

But Biden's comfort in the corridors of power is also part of what Americans are voting for when they choose him over Sanders, with his moral clarity--and go-it-alone attitude.

"That's what leadership is about," Sanders instructed Biden after one particularly bruising exchange on Biden's record. "It's having the guts to take an unpopular position."

Will the two candidates ever unite? Dana Bash of CNN asked.

"He's making it hard for me right now," Biden said with a rueful smile. "I was trying to give him credit for some things. He won't even take the credit."

For Biden, a born politician, a hail-fellow-well-met backslapper, and a realist, Sanders's intransigence is bewildering. But there is reason to question the old-fashioned, comprising approach to politics in the face of pandemic, economic meltdown, and climate collapse.

Biden's climate plans are "nowhere near enough," Sanders said, painting a picture of massive flooding, drought, food insecurity, and populations displaced by global warming.

"This is not a middle-of-the-ground thing," he added. "It is insane we continue to have fracking . . . and to give tens of millions of dollars in tax breaks to the fossil fuel industry."

If Biden says coronavirus is an emergency requiring a response akin to war, Sanders said, "I look at climate change in the exact same way."

Sanders wants to spend billions more than Biden on a transition to renewable energy--a $13 to $14 trillion, massive investment others have dismissed as unrealistic.

But the way things are going is unrealistic as well.

And we may not be able to glad-hand our way out of it.

"It is time to ask how we got where we are," Sanders said in his closing. It is time to ask "where the power is in America . . . who owns the media . . . the legislature." It is time "to rethink America," to try to make it "a country where we care about each other, not "a nation of greed and corruption."

Biden's pitch is: "We need someone who can bring the world together again." In his closing, he spoke in a warmer, more personal tone about people who are fearful of losing everything in the current crisis. His demeanor, as much as his policy positions, says he is the guy who can unite us.

Biden speaks in a colloquial, folksy way, yet clearly knows his way around the White House, Congress, and the corporate suite. Sure, he has taken money from big special interests. But so have nearly all of his colleagues. He knows how the game is played. He is not alarmed or angry.

And that's the rub. As Biden walked over to the desk to schmooze with the CNN and Univision moderators, and Sanders departed with a curt wave, it seemed pretty clear where things are headed.

The media, the political establishment, and, recently, most Democratic primary voters--especially the older ones--are more comfortable with Biden and his pitch to restore "normalcy" than with Sanders's talk of revolution.

But normal may not be coming back, no matter who is elected.

Quarantined at home with my middle- and high-school-age kids and two of my college-age daughter's friends, all of whom are suddenly on an indefinite break from school, I took a poll of our cozy focus group. The spectacle of two old white men yelling at each other was wearying to this young audience. But they were far more open to Sanders's points than Biden's.

After all, they are going to have to live in the world we leave them. And Sanders seems much more serious about confronting that.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Last night's Democratic candidate debate, held amid the coronavirus crisis in a nearly empty CNN studio in Washington, D.C., provided voters with what might be their final chance to see, in stark relief, the choice between the two remaining contenders for the Democratic nomination: Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders.

With Biden on a path to wrap up the most delegates after the last round of primaries, the campaigns seemed to be inching toward some sort of detente, with Sanders acknowledging Biden as the likely nominee, and Biden adopting some progressive policy positions, recognizing Sanders's leadership of a movement that is necessary to a Democratic victory.

The coronavirus pandemic exposes the huge cracks in our society that Sanders has been pointing out all along.

Would the two candidates begin to form a coherent, unified position for addressing the pandemic and ending the disastrous presidency of Donald Trump?

Nope.

Instead, we got two hours of heated, personal exchanges, rehashing of old votes, ("yes you did," "no I didn't"), a truly reprehensible round of red-baiting of Sanders, and an ideological collision over radical change versus incrementalism that was never adequately worked out.

Biden did commit to choosing a woman as a running mate, which is big news. It also suggests that he might be getting ready to pick Elizabeth Warren, whose policy positions he has been adopting lately--an olive branch to the progressive party base.

But when Biden and Sanders left the debate stage they were a long way from coming together.

Sanders is absolutely right that the current public-health crisis, and its economic aftershocks, expose the great vulnerability of our unequal, increasingly unjust society.

As he repeatedly pointed out, "We are the only major nation on Earth without guaranteed health care." We spend twice as much per capita on health care than other developed countries, but our patchwork of private insurance and the millions of Amercians who can't afford to see a doctor leave us woefully unprepared to launch an effective, coordinated response to this pandemic.

Add to that the desperate situation of workers who can't take paid sick leave, and the majority of Americans living paycheck to paycheck who can't ride out the sudden closure of their workplaces, and you have a powerful argument for Sanders's basic arguments for Medicare for All, increasing the minimum wage, taxing the rich and corporations, and restoring the social safety net.

The coronavirus pandemic exposes the huge cracks in our society that Sanders has been pointing out all along.

Biden's response was to say the nation is in the throes of "a national emergency" that "has nothing to do with Bernie's Medicare for All."

The heart of the Biden argument--and what has persuaded voters from Michigan to Mississippi--is that the Sanders revolution is unrealistic. Sanders has the moral high ground. Biden doesn't dispute it. But getting to Medicare for All would take years, he said, and people need action right now.

If Biden says coronavirus is an emergency requiring a response akin to war, Sanders said, "I look at climate change in the exact same way."

Biden's related argument is that he knows how to get things done--from diplomacy with foreign leaders to figuring out how to get a bill through a divided Congress.

I suspect Biden, like many viewers, thought Sanders might be ready to concede the point. It seemed possible that Sanders might want to lecture Biden on the right thing to do, and then Biden, as he has been doing in recent days, would jovially agree that Sanders has some great ideas and begin to co-opt them and make them his own. That's how the primary process ordinarily works.

But these are not ordinary times. And Sanders is not an ordinary politician.

Instead, Sanders dredged up Biden's history--supporting the bank bailout; his floor speeches supporting the budget-balancing Bowles-Simpson Act, which included cuts to Social Security and Medicare; his contributions from the pharmaceutical industry; his votes for the Iraq War and the Defense of Marriage Act (both of which he has since acknowledged were mistakes); and his multiple votes for the anti-abortion Hyde Amendment barring the use of federal funds for abortion.

Biden, helped along by the moderators, got his revenge by attacking Sanders for his long-ago praise of literacy rates in Cuba and in Nicaragua under the Sandinistas, and spuriously suggesting that Sanders might coddle the authoritarian government of China. It was transparent red-baiting and just plain ugly.

In several instances, Sanders seemed unwilling to take yes for an answer. Biden has adopted Senator Elizabeth Warren's bankruptcy bill and part of Sanders's free-college plan that would cover tuition at public universities for families that earn less than $125,000 per year.

But the bankruptcy bill Warren seeks to undo is one Biden helped to write, Sanders pointed out.

"I did not!" Biden huffed.

Sanders had plenty of material. Biden, as a Senator from Delaware, spent years developing a cozy relationship with the banking industry headquartered there. He has a long record of less-than-perfect populism.

But Biden's comfort in the corridors of power is also part of what Americans are voting for when they choose him over Sanders, with his moral clarity--and go-it-alone attitude.

"That's what leadership is about," Sanders instructed Biden after one particularly bruising exchange on Biden's record. "It's having the guts to take an unpopular position."

Will the two candidates ever unite? Dana Bash of CNN asked.

"He's making it hard for me right now," Biden said with a rueful smile. "I was trying to give him credit for some things. He won't even take the credit."

For Biden, a born politician, a hail-fellow-well-met backslapper, and a realist, Sanders's intransigence is bewildering. But there is reason to question the old-fashioned, comprising approach to politics in the face of pandemic, economic meltdown, and climate collapse.

Biden's climate plans are "nowhere near enough," Sanders said, painting a picture of massive flooding, drought, food insecurity, and populations displaced by global warming.

"This is not a middle-of-the-ground thing," he added. "It is insane we continue to have fracking . . . and to give tens of millions of dollars in tax breaks to the fossil fuel industry."

If Biden says coronavirus is an emergency requiring a response akin to war, Sanders said, "I look at climate change in the exact same way."

Sanders wants to spend billions more than Biden on a transition to renewable energy--a $13 to $14 trillion, massive investment others have dismissed as unrealistic.

But the way things are going is unrealistic as well.

And we may not be able to glad-hand our way out of it.

"It is time to ask how we got where we are," Sanders said in his closing. It is time to ask "where the power is in America . . . who owns the media . . . the legislature." It is time "to rethink America," to try to make it "a country where we care about each other, not "a nation of greed and corruption."

Biden's pitch is: "We need someone who can bring the world together again." In his closing, he spoke in a warmer, more personal tone about people who are fearful of losing everything in the current crisis. His demeanor, as much as his policy positions, says he is the guy who can unite us.

Biden speaks in a colloquial, folksy way, yet clearly knows his way around the White House, Congress, and the corporate suite. Sure, he has taken money from big special interests. But so have nearly all of his colleagues. He knows how the game is played. He is not alarmed or angry.

And that's the rub. As Biden walked over to the desk to schmooze with the CNN and Univision moderators, and Sanders departed with a curt wave, it seemed pretty clear where things are headed.

The media, the political establishment, and, recently, most Democratic primary voters--especially the older ones--are more comfortable with Biden and his pitch to restore "normalcy" than with Sanders's talk of revolution.

But normal may not be coming back, no matter who is elected.

Quarantined at home with my middle- and high-school-age kids and two of my college-age daughter's friends, all of whom are suddenly on an indefinite break from school, I took a poll of our cozy focus group. The spectacle of two old white men yelling at each other was wearying to this young audience. But they were far more open to Sanders's points than Biden's.

After all, they are going to have to live in the world we leave them. And Sanders seems much more serious about confronting that.

Last night's Democratic candidate debate, held amid the coronavirus crisis in a nearly empty CNN studio in Washington, D.C., provided voters with what might be their final chance to see, in stark relief, the choice between the two remaining contenders for the Democratic nomination: Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders.

With Biden on a path to wrap up the most delegates after the last round of primaries, the campaigns seemed to be inching toward some sort of detente, with Sanders acknowledging Biden as the likely nominee, and Biden adopting some progressive policy positions, recognizing Sanders's leadership of a movement that is necessary to a Democratic victory.

The coronavirus pandemic exposes the huge cracks in our society that Sanders has been pointing out all along.

Would the two candidates begin to form a coherent, unified position for addressing the pandemic and ending the disastrous presidency of Donald Trump?

Nope.

Instead, we got two hours of heated, personal exchanges, rehashing of old votes, ("yes you did," "no I didn't"), a truly reprehensible round of red-baiting of Sanders, and an ideological collision over radical change versus incrementalism that was never adequately worked out.

Biden did commit to choosing a woman as a running mate, which is big news. It also suggests that he might be getting ready to pick Elizabeth Warren, whose policy positions he has been adopting lately--an olive branch to the progressive party base.

But when Biden and Sanders left the debate stage they were a long way from coming together.

Sanders is absolutely right that the current public-health crisis, and its economic aftershocks, expose the great vulnerability of our unequal, increasingly unjust society.

As he repeatedly pointed out, "We are the only major nation on Earth without guaranteed health care." We spend twice as much per capita on health care than other developed countries, but our patchwork of private insurance and the millions of Amercians who can't afford to see a doctor leave us woefully unprepared to launch an effective, coordinated response to this pandemic.

Add to that the desperate situation of workers who can't take paid sick leave, and the majority of Americans living paycheck to paycheck who can't ride out the sudden closure of their workplaces, and you have a powerful argument for Sanders's basic arguments for Medicare for All, increasing the minimum wage, taxing the rich and corporations, and restoring the social safety net.

The coronavirus pandemic exposes the huge cracks in our society that Sanders has been pointing out all along.

Biden's response was to say the nation is in the throes of "a national emergency" that "has nothing to do with Bernie's Medicare for All."

The heart of the Biden argument--and what has persuaded voters from Michigan to Mississippi--is that the Sanders revolution is unrealistic. Sanders has the moral high ground. Biden doesn't dispute it. But getting to Medicare for All would take years, he said, and people need action right now.

If Biden says coronavirus is an emergency requiring a response akin to war, Sanders said, "I look at climate change in the exact same way."

Biden's related argument is that he knows how to get things done--from diplomacy with foreign leaders to figuring out how to get a bill through a divided Congress.

I suspect Biden, like many viewers, thought Sanders might be ready to concede the point. It seemed possible that Sanders might want to lecture Biden on the right thing to do, and then Biden, as he has been doing in recent days, would jovially agree that Sanders has some great ideas and begin to co-opt them and make them his own. That's how the primary process ordinarily works.

But these are not ordinary times. And Sanders is not an ordinary politician.

Instead, Sanders dredged up Biden's history--supporting the bank bailout; his floor speeches supporting the budget-balancing Bowles-Simpson Act, which included cuts to Social Security and Medicare; his contributions from the pharmaceutical industry; his votes for the Iraq War and the Defense of Marriage Act (both of which he has since acknowledged were mistakes); and his multiple votes for the anti-abortion Hyde Amendment barring the use of federal funds for abortion.

Biden, helped along by the moderators, got his revenge by attacking Sanders for his long-ago praise of literacy rates in Cuba and in Nicaragua under the Sandinistas, and spuriously suggesting that Sanders might coddle the authoritarian government of China. It was transparent red-baiting and just plain ugly.

In several instances, Sanders seemed unwilling to take yes for an answer. Biden has adopted Senator Elizabeth Warren's bankruptcy bill and part of Sanders's free-college plan that would cover tuition at public universities for families that earn less than $125,000 per year.

But the bankruptcy bill Warren seeks to undo is one Biden helped to write, Sanders pointed out.

"I did not!" Biden huffed.

Sanders had plenty of material. Biden, as a Senator from Delaware, spent years developing a cozy relationship with the banking industry headquartered there. He has a long record of less-than-perfect populism.

But Biden's comfort in the corridors of power is also part of what Americans are voting for when they choose him over Sanders, with his moral clarity--and go-it-alone attitude.

"That's what leadership is about," Sanders instructed Biden after one particularly bruising exchange on Biden's record. "It's having the guts to take an unpopular position."

Will the two candidates ever unite? Dana Bash of CNN asked.

"He's making it hard for me right now," Biden said with a rueful smile. "I was trying to give him credit for some things. He won't even take the credit."

For Biden, a born politician, a hail-fellow-well-met backslapper, and a realist, Sanders's intransigence is bewildering. But there is reason to question the old-fashioned, comprising approach to politics in the face of pandemic, economic meltdown, and climate collapse.

Biden's climate plans are "nowhere near enough," Sanders said, painting a picture of massive flooding, drought, food insecurity, and populations displaced by global warming.

"This is not a middle-of-the-ground thing," he added. "It is insane we continue to have fracking . . . and to give tens of millions of dollars in tax breaks to the fossil fuel industry."

If Biden says coronavirus is an emergency requiring a response akin to war, Sanders said, "I look at climate change in the exact same way."

Sanders wants to spend billions more than Biden on a transition to renewable energy--a $13 to $14 trillion, massive investment others have dismissed as unrealistic.

But the way things are going is unrealistic as well.

And we may not be able to glad-hand our way out of it.

"It is time to ask how we got where we are," Sanders said in his closing. It is time to ask "where the power is in America . . . who owns the media . . . the legislature." It is time "to rethink America," to try to make it "a country where we care about each other, not "a nation of greed and corruption."

Biden's pitch is: "We need someone who can bring the world together again." In his closing, he spoke in a warmer, more personal tone about people who are fearful of losing everything in the current crisis. His demeanor, as much as his policy positions, says he is the guy who can unite us.

Biden speaks in a colloquial, folksy way, yet clearly knows his way around the White House, Congress, and the corporate suite. Sure, he has taken money from big special interests. But so have nearly all of his colleagues. He knows how the game is played. He is not alarmed or angry.

And that's the rub. As Biden walked over to the desk to schmooze with the CNN and Univision moderators, and Sanders departed with a curt wave, it seemed pretty clear where things are headed.

The media, the political establishment, and, recently, most Democratic primary voters--especially the older ones--are more comfortable with Biden and his pitch to restore "normalcy" than with Sanders's talk of revolution.

But normal may not be coming back, no matter who is elected.

Quarantined at home with my middle- and high-school-age kids and two of my college-age daughter's friends, all of whom are suddenly on an indefinite break from school, I took a poll of our cozy focus group. The spectacle of two old white men yelling at each other was wearying to this young audience. But they were far more open to Sanders's points than Biden's.

After all, they are going to have to live in the world we leave them. And Sanders seems much more serious about confronting that.