SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

One Detroit Center in Detroit, where bus drivers of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 26 kept 90% of the city's buses in terminals on March 17 by refusing to work without adequate personal protective equipment. (Photo: Creative Commons)

While the coronavirus spreads, another contagion is brewing - a contagion of strikes for protection against the coronavirus.

Early Tuesday morning, March 17, Detroit bus drivers gathered at dawn at the city's two major terminals. They were worried about coronavirus. The day before, the state had closed all restaurants, leaving many drivers without access to bathrooms and with no place to wash their hands. Drivers had no gloves, disinfectant wipes, or masks. Buses were poorly cleaned. The drivers decided they weren't going to go to work without safety precautions. 90% of the buses remained in the terminals that morning. According to Glenn Tolbert, president of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 26, the drivers "had been discussing it" and "they just decided they weren't going to work." They "called us and asked us to stand by them, and that's what we do." The mayor came to talk with the drivers, and bus service was shut down for the day, due, officials said, to "the driver shortage." Tolbert apologized for inconveniencing passengers, but explained, "we didn't want to get sick and affect the public, and we didn't want the public to get sick and affect us."

By the next day the drivers had won all their demands. Bus fares were suspended for the duration of the pandemic and riders allowed to enter and exit by the rear door so they wouldn't have to congregate around the driver. A seat was going to be left empty behind the driver to provide social distance. Drivers would get gloves and disinfectant wipes and masks "upon request whenever available." More cleaning staff were hired and given new instructions on sanitizing and supplied more concentrated disinfectant. If no toilets were available port-a-potties would be provided.

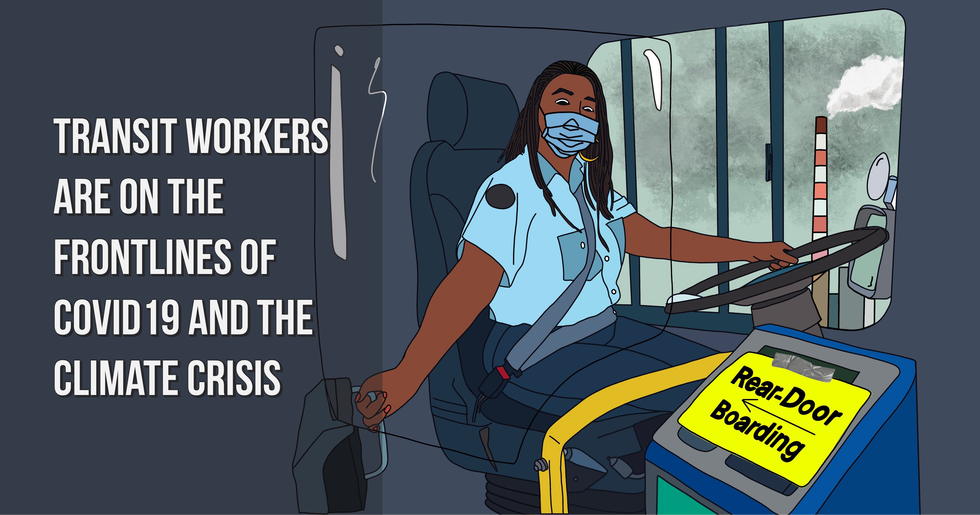

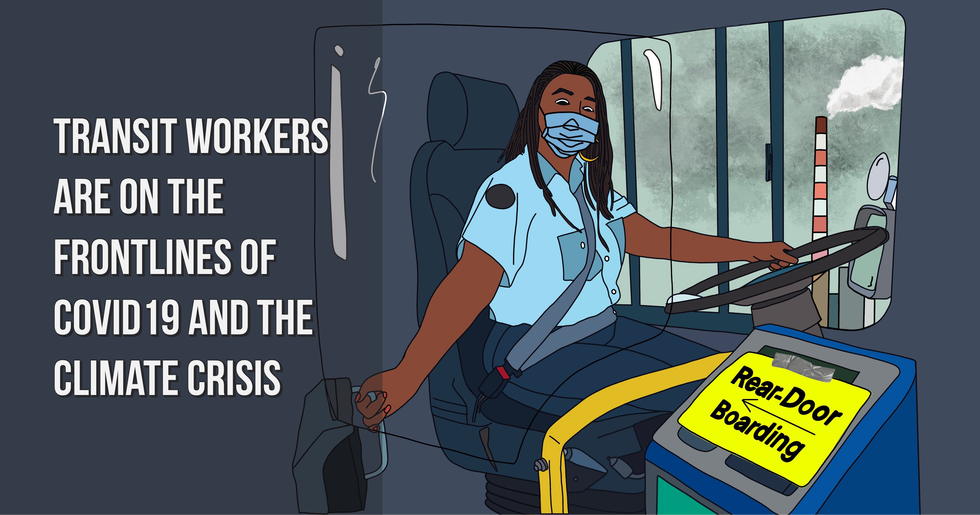

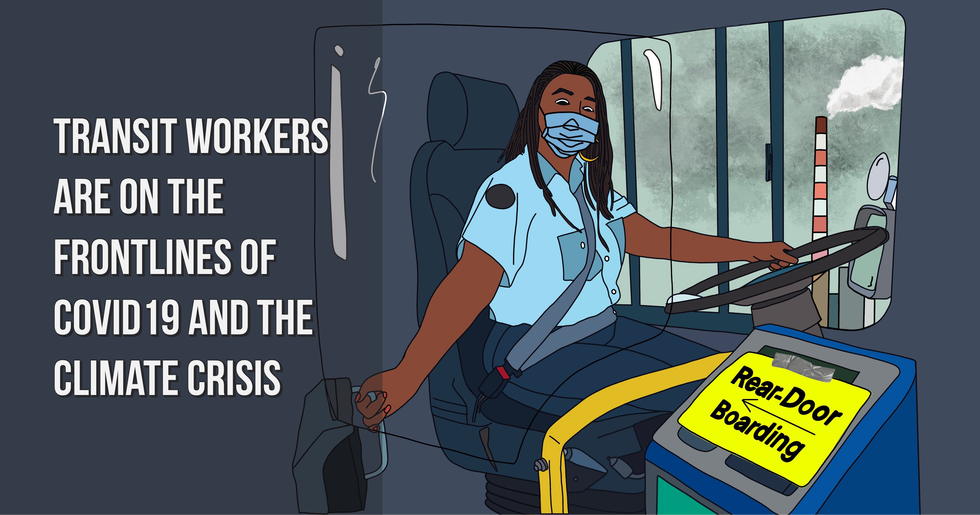

Graphic: Taylor Mayes, Connecticut Roundtable on Climate and Jobs.

In an op ed in the New York Times, former Times labor reporter Steven Greenhouse described similar strikes that have broken out within the last two weeks. They include:

Just since Greenhouse's article there have been further coronavirus walkouts by Staten Island Amazon warehouse workers, Whole Foods workers, and Instacart workers nationwide.

Greenhouse writes, "As often happens when workers finally flex their collective muscles, their actions have gotten results." Birmingham had passengers enter by the rear doors, and limited passengers to 19 per bus to provide social distancing. San Jose McDonald's supplied gloves and soap.

Other variants of the coronavirus strike have begun to appear as well:

In Durham and Raleigh,North Carolina, nearly a hundred restaurant and retail workers from McDonalds's, Family Dollar, Food Lion, Walmart, and a Shell gas station held a one-day "digital strike." Unable to demonstrate in the streets because of a county stay-at-home order, they gathered from their homes via a Zoom call and shared their stories and grievances. Workers told how they had to mix their own homemade sanitizer and how customers brought them masks but their manager forbade them to wear the masks lest they alarm customers. The strikers were members of NC Raise Up, a chapter of the national Fight for $15 and a Union movement. They won support from a city council member, a local doctor, and local justice organizations.

In Lynn, Massachusetts, General Electric factory workers walked off the job and, standing six feet apart, held a silent protest to demand that GE convert its jet engine facilities to make ventilators. Meanwhile, other GE workers marched - six feet apart - at the company's Boston headquarters. The protesting workers were members of the Industrial Division of the Communication Workers of America (IUE-CWA). The GE Healthcare Division already produces ventilators on a large scale. GE had just announced it was laying off 2,600 aviation workers. CWA President Chris Shelton said, "Our country depends on these highly skilled workers and now they're wondering why they are facing layoffs instead of having the opportunity to use their unbelievable skills to help save lives."

Photo: Radar being manufactured for the U.S. Navy in a General Electric factory, June 13, 1943. Shown: Assembling radar equipment. The women were previously builders of radio equipment for civilian use. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (2017/06/06)

These actions had diverse relationships to unions. Some, like the GE protests, were union-organized. Some, like the Detroit bus drivers' walkout, were organized by rank-and-file workers but won union support. Some were organized by non-union worker groups, such as the Instacart Shoppers and Gig Workers Collective and the NC Raise Up, an affiliate of the SEIU-backed Fight for $15.

Notably absent from the strikes so far are healthcare workers. They are probably the most exposed to coronavirus infection of all, and they and their unions have been outspoken in demanding personal protective equipment (PPE) and protective practices. But, as one nurse put it, healthcare workers don't want to strike because they want to be in there working to save lives. That doesn't mean they won't strike if they have to. Healthcare workers have instead been holding demonstrations in New York, Georgia, Illinois, California, and elsewhere around the country to demand PPE.

As a labor historian, the closest thing I can think of to the spread of coronavirus strikes was the epidemic of sitdown strikes that spread across the country in the mid-1930s. The sitdowns had started in Akron, Ohio when a handful of rubber workers sat down on the job; in the following months Akron workers conducted scores of sitdowns to fight speed-up, arbitrary firings, and other grievances. The sitdown strike was adopted by autoworkers, and in 1937 workers in Flint, Michigan used the tactic to halt the giant General Motors Corporation and force it to recognize the United Auto Workers union. It was then that the sitdown really became an epidemic. In addition to hundreds of sitdowns by workers, there were others in welfare offices, employment agencies, prisons, colleges, and movie theaters. In March 1937 alone, there were 170 industrial sitdowns with 167,210 participants.

Workers in Italy have given some indication of what such an epidemic of worker resistance in response to the coronavirus pandemic might look like. Italy hard hit by infection and, like the United States, its government was woefully slow in responding and its employers resisted taking effective public health measures.

An article by Leopoldo Tartaglia of the CGIL, Italy's largest union federation, describes how workers responded. March 12 and 13 were "days of true revolt" in factories, warehouses, and many other sectors of the economy. The metalworkers' unions--FIM CISL, FIOM CGIL and UILM UIL--"called for companies to suspend work until March 22 to sanitize all jobs and equip employees with personal protective equipment." Grocery unions FILCAMS CGIL, FISASCAT CISL, and UILTUCS UIL asked that "food stores and supermarkets close on Saturdays and Sundays and in the evening after 7 p.m." In companies that did not suspend work, especially in the areas hardest hit by the pandemic, "workers, supported by their unions, struck indefinitely until the companies guaranteed safe working conditions."

From the Dalmine steel mills of Bergamo to those of Brescia, from the Fiat-Chrysler plants of Pomigliano in Naples to the Ilva steel plant in Genoa, from the Electrolux factory of Susegana in Treviso to many small and medium-sized companies in Veneto and Emilia Romagna, from the Amazon warehouses in the provinces of Piacenza and Rieti, to the poultry and meat processing companies in the Po Valley, there were thousands of striking workers who came out into the squares and streets, strictly at a safe distance of one meter apart from one another, as prescribed by the government decree. Meanwhile the RSUs (Rappresentanza Sindacale Unitaria, enterprise-based multi-union bodies) entered into negotiations with their respective company managements.

On March 13 the government agreed to convene a meeting by videoconference with unions and employers. Despite resistance from the employer association Confindustria, agreement was reached on a "shared protocol" of measures that companies must take to ensure the health and safety of workers, with a penalty of temporary closure for not complying.

Tartaglia makes clear that Italian labor still has more to do:

For the enterprise-level multi-union bodies and the union confederations, there is a lot of work: making agreements on safety and the protection of income, defending the most precarious workers, fighting to close all non-essential jobs, negotiating with companies and public authorities to close the shops in the evening and on Saturdays and Sundays, and organizing strikes and mobilizations when the bosses try to evade their obligations.

These are struggles and demands for this emergency, but also for the aftermath. Things cannot continue as before. The development model must be changed, the public sector must be relaunched, and austerity, neoliberalism, precariousness, and inequalities must be ended. It is time to end polluting production and to make economic and productive choices capable of stopping climate change.

If the coronavirus strikes continue to spread in the U.S., how might they have the kind of effectiveness that the Italian worker actions had? The strikes so far have been effective in winning some protections and a nationwide wave of them would put tremendous pressure on employers and local and state governments to comply with good public health practices.

But what about national policy to meet public health needs and in particular to ensure the availability of PPE? It is hard to imagine the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Trump administration sitting down to bargain with the representatives of American workers. But that doesn't mean worker action is powerless to affect what they do.

Perhaps the most relevant example is the worker action that forced an end to the 35-day government shutdown and forestalled President Trump from starting a new one. Trump and the Republican Congress were forced to reopen the government when TSA screeners stopped showing up for their jobs and air traffic controllers called out from work, closing major airports, and opponents of the shutdown mobilized to occupy airports and congressional offices. Trump's plans to shut down the government again were warded off in part by calls for mass action and a general strike.

Cascading strikes and other direct actions could have a similar impact today, creating irresistible pressure for federal policy to conform with public health needs. There are a few elements that will need to come together.

First, this is not just a matter for the workers directly affected. Keeping front line workers safe is essential for the safety of all of us. When Association of Flight Attendants-CWA president Sara

Nelson appealed for mass action to end the government shutdown and a general strike to prevent another one, she didn't address her call primarily to government workers. Rather, she told union leaders,

Federal sector unions have their hands full caring for the 800,000 federal workers who are at the tip of the spear. Some would say the answer is for them to walk off the job. I say, "what are you willing to do?" Their destiny is tied up with our destiny--and they don't even have time to ask us for help. Don't wait for an invitation. Get engaged, join or plan a rally, get on a picket line, organize sit-ins at lawmakers' offices. What is the Labor Movement waiting for? Go back with the Fierce Urgency of NOW to talk with your Locals and International unions about all workers joining together--To End this Shutdown with a General Strike.

Nor is protecting workers from infection just a matter for other workers and unions. We need the broadest possible movement backing the workers who are fighting for everybody's safety. Last week the Labor Network for Sustainability held a videoconference of leaders from unions representing directly affected workers and heads of several major environmental organizations. The union leaders told the story of how their members were being devastated by coronavirus and how they were fighting back. The environmental leaders, visibly moved, offered to mobilize their members to support the unions' demands. (More details on this in a future commentary.) The workers who are protecting all of us need backing from consumers, faith communities, and everyone else. Everyone needs to act to protect threatened workers, whether they clean a bus, check out customers in a supermarket, or care for infected patients in a medical facility. As Kelley Cabrera, a registered nurse and president of the New York State Nurses Association's labor bargaining unit at New York's Jacobi Medical Center put it, "We need public support to help us demand further action from the federal government." There are "several ways to ramp up production of PPE and ventilators, but the current administration refuses to use these powers, therefore leaving our frontline staff and patients at risk of infection and death."

As Stephen Greenhouse pointed out, American workers, "fearing retaliation," are often "reluctant to stick their necks out and protest working conditions." Chris Smalls, who walked off the job in a strike for safety at an Amazon fulfillment center in Staten Island this week, was immediately fired for allegedly violating safety regulations. "Because I tried to stand up for something that's right, the company decided to retaliate against me," he said. New York State Attorney General Letitia James announced she was calling for an investigation of the firing by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and mayor Bill De Blasio instructed the city's Commission on Human Rights to investigate Amazon's action immediately.

Both organized labor and the broader public need to demand that no worker be punished for trying to protect their own - and the public's - health. We can take a page from the Fight for $15 playbook and organize to pressure employers not to retaliate against workers who strike for health - and to launch boycotts, publicity campaigns, and other actions against any who do.

Finally, to be effective this worker protection movement needs to move toward unified demands around which workers, unions, allies, and the public can join. While details differ, similar demands are arising in the coronavirus strikes:

These are demands that employers and local, state, and federal governments can meet - if they are put under sufficient pressure.

Last year concerted action forced an end to the government shutdown. Right now concerted action can help protect workers against deadly infection - and contribute to the defeat of the coronavirus pandemic.

For fully annotated list click here.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

While the coronavirus spreads, another contagion is brewing - a contagion of strikes for protection against the coronavirus.

Early Tuesday morning, March 17, Detroit bus drivers gathered at dawn at the city's two major terminals. They were worried about coronavirus. The day before, the state had closed all restaurants, leaving many drivers without access to bathrooms and with no place to wash their hands. Drivers had no gloves, disinfectant wipes, or masks. Buses were poorly cleaned. The drivers decided they weren't going to go to work without safety precautions. 90% of the buses remained in the terminals that morning. According to Glenn Tolbert, president of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 26, the drivers "had been discussing it" and "they just decided they weren't going to work." They "called us and asked us to stand by them, and that's what we do." The mayor came to talk with the drivers, and bus service was shut down for the day, due, officials said, to "the driver shortage." Tolbert apologized for inconveniencing passengers, but explained, "we didn't want to get sick and affect the public, and we didn't want the public to get sick and affect us."

By the next day the drivers had won all their demands. Bus fares were suspended for the duration of the pandemic and riders allowed to enter and exit by the rear door so they wouldn't have to congregate around the driver. A seat was going to be left empty behind the driver to provide social distance. Drivers would get gloves and disinfectant wipes and masks "upon request whenever available." More cleaning staff were hired and given new instructions on sanitizing and supplied more concentrated disinfectant. If no toilets were available port-a-potties would be provided.

Graphic: Taylor Mayes, Connecticut Roundtable on Climate and Jobs.

In an op ed in the New York Times, former Times labor reporter Steven Greenhouse described similar strikes that have broken out within the last two weeks. They include:

Just since Greenhouse's article there have been further coronavirus walkouts by Staten Island Amazon warehouse workers, Whole Foods workers, and Instacart workers nationwide.

Greenhouse writes, "As often happens when workers finally flex their collective muscles, their actions have gotten results." Birmingham had passengers enter by the rear doors, and limited passengers to 19 per bus to provide social distancing. San Jose McDonald's supplied gloves and soap.

Other variants of the coronavirus strike have begun to appear as well:

In Durham and Raleigh,North Carolina, nearly a hundred restaurant and retail workers from McDonalds's, Family Dollar, Food Lion, Walmart, and a Shell gas station held a one-day "digital strike." Unable to demonstrate in the streets because of a county stay-at-home order, they gathered from their homes via a Zoom call and shared their stories and grievances. Workers told how they had to mix their own homemade sanitizer and how customers brought them masks but their manager forbade them to wear the masks lest they alarm customers. The strikers were members of NC Raise Up, a chapter of the national Fight for $15 and a Union movement. They won support from a city council member, a local doctor, and local justice organizations.

In Lynn, Massachusetts, General Electric factory workers walked off the job and, standing six feet apart, held a silent protest to demand that GE convert its jet engine facilities to make ventilators. Meanwhile, other GE workers marched - six feet apart - at the company's Boston headquarters. The protesting workers were members of the Industrial Division of the Communication Workers of America (IUE-CWA). The GE Healthcare Division already produces ventilators on a large scale. GE had just announced it was laying off 2,600 aviation workers. CWA President Chris Shelton said, "Our country depends on these highly skilled workers and now they're wondering why they are facing layoffs instead of having the opportunity to use their unbelievable skills to help save lives."

Photo: Radar being manufactured for the U.S. Navy in a General Electric factory, June 13, 1943. Shown: Assembling radar equipment. The women were previously builders of radio equipment for civilian use. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (2017/06/06)

These actions had diverse relationships to unions. Some, like the GE protests, were union-organized. Some, like the Detroit bus drivers' walkout, were organized by rank-and-file workers but won union support. Some were organized by non-union worker groups, such as the Instacart Shoppers and Gig Workers Collective and the NC Raise Up, an affiliate of the SEIU-backed Fight for $15.

Notably absent from the strikes so far are healthcare workers. They are probably the most exposed to coronavirus infection of all, and they and their unions have been outspoken in demanding personal protective equipment (PPE) and protective practices. But, as one nurse put it, healthcare workers don't want to strike because they want to be in there working to save lives. That doesn't mean they won't strike if they have to. Healthcare workers have instead been holding demonstrations in New York, Georgia, Illinois, California, and elsewhere around the country to demand PPE.

As a labor historian, the closest thing I can think of to the spread of coronavirus strikes was the epidemic of sitdown strikes that spread across the country in the mid-1930s. The sitdowns had started in Akron, Ohio when a handful of rubber workers sat down on the job; in the following months Akron workers conducted scores of sitdowns to fight speed-up, arbitrary firings, and other grievances. The sitdown strike was adopted by autoworkers, and in 1937 workers in Flint, Michigan used the tactic to halt the giant General Motors Corporation and force it to recognize the United Auto Workers union. It was then that the sitdown really became an epidemic. In addition to hundreds of sitdowns by workers, there were others in welfare offices, employment agencies, prisons, colleges, and movie theaters. In March 1937 alone, there were 170 industrial sitdowns with 167,210 participants.

Workers in Italy have given some indication of what such an epidemic of worker resistance in response to the coronavirus pandemic might look like. Italy hard hit by infection and, like the United States, its government was woefully slow in responding and its employers resisted taking effective public health measures.

An article by Leopoldo Tartaglia of the CGIL, Italy's largest union federation, describes how workers responded. March 12 and 13 were "days of true revolt" in factories, warehouses, and many other sectors of the economy. The metalworkers' unions--FIM CISL, FIOM CGIL and UILM UIL--"called for companies to suspend work until March 22 to sanitize all jobs and equip employees with personal protective equipment." Grocery unions FILCAMS CGIL, FISASCAT CISL, and UILTUCS UIL asked that "food stores and supermarkets close on Saturdays and Sundays and in the evening after 7 p.m." In companies that did not suspend work, especially in the areas hardest hit by the pandemic, "workers, supported by their unions, struck indefinitely until the companies guaranteed safe working conditions."

From the Dalmine steel mills of Bergamo to those of Brescia, from the Fiat-Chrysler plants of Pomigliano in Naples to the Ilva steel plant in Genoa, from the Electrolux factory of Susegana in Treviso to many small and medium-sized companies in Veneto and Emilia Romagna, from the Amazon warehouses in the provinces of Piacenza and Rieti, to the poultry and meat processing companies in the Po Valley, there were thousands of striking workers who came out into the squares and streets, strictly at a safe distance of one meter apart from one another, as prescribed by the government decree. Meanwhile the RSUs (Rappresentanza Sindacale Unitaria, enterprise-based multi-union bodies) entered into negotiations with their respective company managements.

On March 13 the government agreed to convene a meeting by videoconference with unions and employers. Despite resistance from the employer association Confindustria, agreement was reached on a "shared protocol" of measures that companies must take to ensure the health and safety of workers, with a penalty of temporary closure for not complying.

Tartaglia makes clear that Italian labor still has more to do:

For the enterprise-level multi-union bodies and the union confederations, there is a lot of work: making agreements on safety and the protection of income, defending the most precarious workers, fighting to close all non-essential jobs, negotiating with companies and public authorities to close the shops in the evening and on Saturdays and Sundays, and organizing strikes and mobilizations when the bosses try to evade their obligations.

These are struggles and demands for this emergency, but also for the aftermath. Things cannot continue as before. The development model must be changed, the public sector must be relaunched, and austerity, neoliberalism, precariousness, and inequalities must be ended. It is time to end polluting production and to make economic and productive choices capable of stopping climate change.

If the coronavirus strikes continue to spread in the U.S., how might they have the kind of effectiveness that the Italian worker actions had? The strikes so far have been effective in winning some protections and a nationwide wave of them would put tremendous pressure on employers and local and state governments to comply with good public health practices.

But what about national policy to meet public health needs and in particular to ensure the availability of PPE? It is hard to imagine the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Trump administration sitting down to bargain with the representatives of American workers. But that doesn't mean worker action is powerless to affect what they do.

Perhaps the most relevant example is the worker action that forced an end to the 35-day government shutdown and forestalled President Trump from starting a new one. Trump and the Republican Congress were forced to reopen the government when TSA screeners stopped showing up for their jobs and air traffic controllers called out from work, closing major airports, and opponents of the shutdown mobilized to occupy airports and congressional offices. Trump's plans to shut down the government again were warded off in part by calls for mass action and a general strike.

Cascading strikes and other direct actions could have a similar impact today, creating irresistible pressure for federal policy to conform with public health needs. There are a few elements that will need to come together.

First, this is not just a matter for the workers directly affected. Keeping front line workers safe is essential for the safety of all of us. When Association of Flight Attendants-CWA president Sara

Nelson appealed for mass action to end the government shutdown and a general strike to prevent another one, she didn't address her call primarily to government workers. Rather, she told union leaders,

Federal sector unions have their hands full caring for the 800,000 federal workers who are at the tip of the spear. Some would say the answer is for them to walk off the job. I say, "what are you willing to do?" Their destiny is tied up with our destiny--and they don't even have time to ask us for help. Don't wait for an invitation. Get engaged, join or plan a rally, get on a picket line, organize sit-ins at lawmakers' offices. What is the Labor Movement waiting for? Go back with the Fierce Urgency of NOW to talk with your Locals and International unions about all workers joining together--To End this Shutdown with a General Strike.

Nor is protecting workers from infection just a matter for other workers and unions. We need the broadest possible movement backing the workers who are fighting for everybody's safety. Last week the Labor Network for Sustainability held a videoconference of leaders from unions representing directly affected workers and heads of several major environmental organizations. The union leaders told the story of how their members were being devastated by coronavirus and how they were fighting back. The environmental leaders, visibly moved, offered to mobilize their members to support the unions' demands. (More details on this in a future commentary.) The workers who are protecting all of us need backing from consumers, faith communities, and everyone else. Everyone needs to act to protect threatened workers, whether they clean a bus, check out customers in a supermarket, or care for infected patients in a medical facility. As Kelley Cabrera, a registered nurse and president of the New York State Nurses Association's labor bargaining unit at New York's Jacobi Medical Center put it, "We need public support to help us demand further action from the federal government." There are "several ways to ramp up production of PPE and ventilators, but the current administration refuses to use these powers, therefore leaving our frontline staff and patients at risk of infection and death."

As Stephen Greenhouse pointed out, American workers, "fearing retaliation," are often "reluctant to stick their necks out and protest working conditions." Chris Smalls, who walked off the job in a strike for safety at an Amazon fulfillment center in Staten Island this week, was immediately fired for allegedly violating safety regulations. "Because I tried to stand up for something that's right, the company decided to retaliate against me," he said. New York State Attorney General Letitia James announced she was calling for an investigation of the firing by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and mayor Bill De Blasio instructed the city's Commission on Human Rights to investigate Amazon's action immediately.

Both organized labor and the broader public need to demand that no worker be punished for trying to protect their own - and the public's - health. We can take a page from the Fight for $15 playbook and organize to pressure employers not to retaliate against workers who strike for health - and to launch boycotts, publicity campaigns, and other actions against any who do.

Finally, to be effective this worker protection movement needs to move toward unified demands around which workers, unions, allies, and the public can join. While details differ, similar demands are arising in the coronavirus strikes:

These are demands that employers and local, state, and federal governments can meet - if they are put under sufficient pressure.

Last year concerted action forced an end to the government shutdown. Right now concerted action can help protect workers against deadly infection - and contribute to the defeat of the coronavirus pandemic.

For fully annotated list click here.

While the coronavirus spreads, another contagion is brewing - a contagion of strikes for protection against the coronavirus.

Early Tuesday morning, March 17, Detroit bus drivers gathered at dawn at the city's two major terminals. They were worried about coronavirus. The day before, the state had closed all restaurants, leaving many drivers without access to bathrooms and with no place to wash their hands. Drivers had no gloves, disinfectant wipes, or masks. Buses were poorly cleaned. The drivers decided they weren't going to go to work without safety precautions. 90% of the buses remained in the terminals that morning. According to Glenn Tolbert, president of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 26, the drivers "had been discussing it" and "they just decided they weren't going to work." They "called us and asked us to stand by them, and that's what we do." The mayor came to talk with the drivers, and bus service was shut down for the day, due, officials said, to "the driver shortage." Tolbert apologized for inconveniencing passengers, but explained, "we didn't want to get sick and affect the public, and we didn't want the public to get sick and affect us."

By the next day the drivers had won all their demands. Bus fares were suspended for the duration of the pandemic and riders allowed to enter and exit by the rear door so they wouldn't have to congregate around the driver. A seat was going to be left empty behind the driver to provide social distance. Drivers would get gloves and disinfectant wipes and masks "upon request whenever available." More cleaning staff were hired and given new instructions on sanitizing and supplied more concentrated disinfectant. If no toilets were available port-a-potties would be provided.

Graphic: Taylor Mayes, Connecticut Roundtable on Climate and Jobs.

In an op ed in the New York Times, former Times labor reporter Steven Greenhouse described similar strikes that have broken out within the last two weeks. They include:

Just since Greenhouse's article there have been further coronavirus walkouts by Staten Island Amazon warehouse workers, Whole Foods workers, and Instacart workers nationwide.

Greenhouse writes, "As often happens when workers finally flex their collective muscles, their actions have gotten results." Birmingham had passengers enter by the rear doors, and limited passengers to 19 per bus to provide social distancing. San Jose McDonald's supplied gloves and soap.

Other variants of the coronavirus strike have begun to appear as well:

In Durham and Raleigh,North Carolina, nearly a hundred restaurant and retail workers from McDonalds's, Family Dollar, Food Lion, Walmart, and a Shell gas station held a one-day "digital strike." Unable to demonstrate in the streets because of a county stay-at-home order, they gathered from their homes via a Zoom call and shared their stories and grievances. Workers told how they had to mix their own homemade sanitizer and how customers brought them masks but their manager forbade them to wear the masks lest they alarm customers. The strikers were members of NC Raise Up, a chapter of the national Fight for $15 and a Union movement. They won support from a city council member, a local doctor, and local justice organizations.

In Lynn, Massachusetts, General Electric factory workers walked off the job and, standing six feet apart, held a silent protest to demand that GE convert its jet engine facilities to make ventilators. Meanwhile, other GE workers marched - six feet apart - at the company's Boston headquarters. The protesting workers were members of the Industrial Division of the Communication Workers of America (IUE-CWA). The GE Healthcare Division already produces ventilators on a large scale. GE had just announced it was laying off 2,600 aviation workers. CWA President Chris Shelton said, "Our country depends on these highly skilled workers and now they're wondering why they are facing layoffs instead of having the opportunity to use their unbelievable skills to help save lives."

Photo: Radar being manufactured for the U.S. Navy in a General Electric factory, June 13, 1943. Shown: Assembling radar equipment. The women were previously builders of radio equipment for civilian use. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (2017/06/06)

These actions had diverse relationships to unions. Some, like the GE protests, were union-organized. Some, like the Detroit bus drivers' walkout, were organized by rank-and-file workers but won union support. Some were organized by non-union worker groups, such as the Instacart Shoppers and Gig Workers Collective and the NC Raise Up, an affiliate of the SEIU-backed Fight for $15.

Notably absent from the strikes so far are healthcare workers. They are probably the most exposed to coronavirus infection of all, and they and their unions have been outspoken in demanding personal protective equipment (PPE) and protective practices. But, as one nurse put it, healthcare workers don't want to strike because they want to be in there working to save lives. That doesn't mean they won't strike if they have to. Healthcare workers have instead been holding demonstrations in New York, Georgia, Illinois, California, and elsewhere around the country to demand PPE.

As a labor historian, the closest thing I can think of to the spread of coronavirus strikes was the epidemic of sitdown strikes that spread across the country in the mid-1930s. The sitdowns had started in Akron, Ohio when a handful of rubber workers sat down on the job; in the following months Akron workers conducted scores of sitdowns to fight speed-up, arbitrary firings, and other grievances. The sitdown strike was adopted by autoworkers, and in 1937 workers in Flint, Michigan used the tactic to halt the giant General Motors Corporation and force it to recognize the United Auto Workers union. It was then that the sitdown really became an epidemic. In addition to hundreds of sitdowns by workers, there were others in welfare offices, employment agencies, prisons, colleges, and movie theaters. In March 1937 alone, there were 170 industrial sitdowns with 167,210 participants.

Workers in Italy have given some indication of what such an epidemic of worker resistance in response to the coronavirus pandemic might look like. Italy hard hit by infection and, like the United States, its government was woefully slow in responding and its employers resisted taking effective public health measures.

An article by Leopoldo Tartaglia of the CGIL, Italy's largest union federation, describes how workers responded. March 12 and 13 were "days of true revolt" in factories, warehouses, and many other sectors of the economy. The metalworkers' unions--FIM CISL, FIOM CGIL and UILM UIL--"called for companies to suspend work until March 22 to sanitize all jobs and equip employees with personal protective equipment." Grocery unions FILCAMS CGIL, FISASCAT CISL, and UILTUCS UIL asked that "food stores and supermarkets close on Saturdays and Sundays and in the evening after 7 p.m." In companies that did not suspend work, especially in the areas hardest hit by the pandemic, "workers, supported by their unions, struck indefinitely until the companies guaranteed safe working conditions."

From the Dalmine steel mills of Bergamo to those of Brescia, from the Fiat-Chrysler plants of Pomigliano in Naples to the Ilva steel plant in Genoa, from the Electrolux factory of Susegana in Treviso to many small and medium-sized companies in Veneto and Emilia Romagna, from the Amazon warehouses in the provinces of Piacenza and Rieti, to the poultry and meat processing companies in the Po Valley, there were thousands of striking workers who came out into the squares and streets, strictly at a safe distance of one meter apart from one another, as prescribed by the government decree. Meanwhile the RSUs (Rappresentanza Sindacale Unitaria, enterprise-based multi-union bodies) entered into negotiations with their respective company managements.

On March 13 the government agreed to convene a meeting by videoconference with unions and employers. Despite resistance from the employer association Confindustria, agreement was reached on a "shared protocol" of measures that companies must take to ensure the health and safety of workers, with a penalty of temporary closure for not complying.

Tartaglia makes clear that Italian labor still has more to do:

For the enterprise-level multi-union bodies and the union confederations, there is a lot of work: making agreements on safety and the protection of income, defending the most precarious workers, fighting to close all non-essential jobs, negotiating with companies and public authorities to close the shops in the evening and on Saturdays and Sundays, and organizing strikes and mobilizations when the bosses try to evade their obligations.

These are struggles and demands for this emergency, but also for the aftermath. Things cannot continue as before. The development model must be changed, the public sector must be relaunched, and austerity, neoliberalism, precariousness, and inequalities must be ended. It is time to end polluting production and to make economic and productive choices capable of stopping climate change.

If the coronavirus strikes continue to spread in the U.S., how might they have the kind of effectiveness that the Italian worker actions had? The strikes so far have been effective in winning some protections and a nationwide wave of them would put tremendous pressure on employers and local and state governments to comply with good public health practices.

But what about national policy to meet public health needs and in particular to ensure the availability of PPE? It is hard to imagine the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Trump administration sitting down to bargain with the representatives of American workers. But that doesn't mean worker action is powerless to affect what they do.

Perhaps the most relevant example is the worker action that forced an end to the 35-day government shutdown and forestalled President Trump from starting a new one. Trump and the Republican Congress were forced to reopen the government when TSA screeners stopped showing up for their jobs and air traffic controllers called out from work, closing major airports, and opponents of the shutdown mobilized to occupy airports and congressional offices. Trump's plans to shut down the government again were warded off in part by calls for mass action and a general strike.

Cascading strikes and other direct actions could have a similar impact today, creating irresistible pressure for federal policy to conform with public health needs. There are a few elements that will need to come together.

First, this is not just a matter for the workers directly affected. Keeping front line workers safe is essential for the safety of all of us. When Association of Flight Attendants-CWA president Sara

Nelson appealed for mass action to end the government shutdown and a general strike to prevent another one, she didn't address her call primarily to government workers. Rather, she told union leaders,

Federal sector unions have their hands full caring for the 800,000 federal workers who are at the tip of the spear. Some would say the answer is for them to walk off the job. I say, "what are you willing to do?" Their destiny is tied up with our destiny--and they don't even have time to ask us for help. Don't wait for an invitation. Get engaged, join or plan a rally, get on a picket line, organize sit-ins at lawmakers' offices. What is the Labor Movement waiting for? Go back with the Fierce Urgency of NOW to talk with your Locals and International unions about all workers joining together--To End this Shutdown with a General Strike.

Nor is protecting workers from infection just a matter for other workers and unions. We need the broadest possible movement backing the workers who are fighting for everybody's safety. Last week the Labor Network for Sustainability held a videoconference of leaders from unions representing directly affected workers and heads of several major environmental organizations. The union leaders told the story of how their members were being devastated by coronavirus and how they were fighting back. The environmental leaders, visibly moved, offered to mobilize their members to support the unions' demands. (More details on this in a future commentary.) The workers who are protecting all of us need backing from consumers, faith communities, and everyone else. Everyone needs to act to protect threatened workers, whether they clean a bus, check out customers in a supermarket, or care for infected patients in a medical facility. As Kelley Cabrera, a registered nurse and president of the New York State Nurses Association's labor bargaining unit at New York's Jacobi Medical Center put it, "We need public support to help us demand further action from the federal government." There are "several ways to ramp up production of PPE and ventilators, but the current administration refuses to use these powers, therefore leaving our frontline staff and patients at risk of infection and death."

As Stephen Greenhouse pointed out, American workers, "fearing retaliation," are often "reluctant to stick their necks out and protest working conditions." Chris Smalls, who walked off the job in a strike for safety at an Amazon fulfillment center in Staten Island this week, was immediately fired for allegedly violating safety regulations. "Because I tried to stand up for something that's right, the company decided to retaliate against me," he said. New York State Attorney General Letitia James announced she was calling for an investigation of the firing by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and mayor Bill De Blasio instructed the city's Commission on Human Rights to investigate Amazon's action immediately.

Both organized labor and the broader public need to demand that no worker be punished for trying to protect their own - and the public's - health. We can take a page from the Fight for $15 playbook and organize to pressure employers not to retaliate against workers who strike for health - and to launch boycotts, publicity campaigns, and other actions against any who do.

Finally, to be effective this worker protection movement needs to move toward unified demands around which workers, unions, allies, and the public can join. While details differ, similar demands are arising in the coronavirus strikes:

These are demands that employers and local, state, and federal governments can meet - if they are put under sufficient pressure.

Last year concerted action forced an end to the government shutdown. Right now concerted action can help protect workers against deadly infection - and contribute to the defeat of the coronavirus pandemic.

For fully annotated list click here.