April's unemployment rate is still an underestimate of the actual number of unemployed workers. It would be higher if all the people who lost their jobs had actually remained in the labor force. (Photo: Witthaya Prasongsin/iStock/Getty Images)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

April's unemployment rate is still an underestimate of the actual number of unemployed workers. It would be higher if all the people who lost their jobs had actually remained in the labor force. (Photo: Witthaya Prasongsin/iStock/Getty Images)

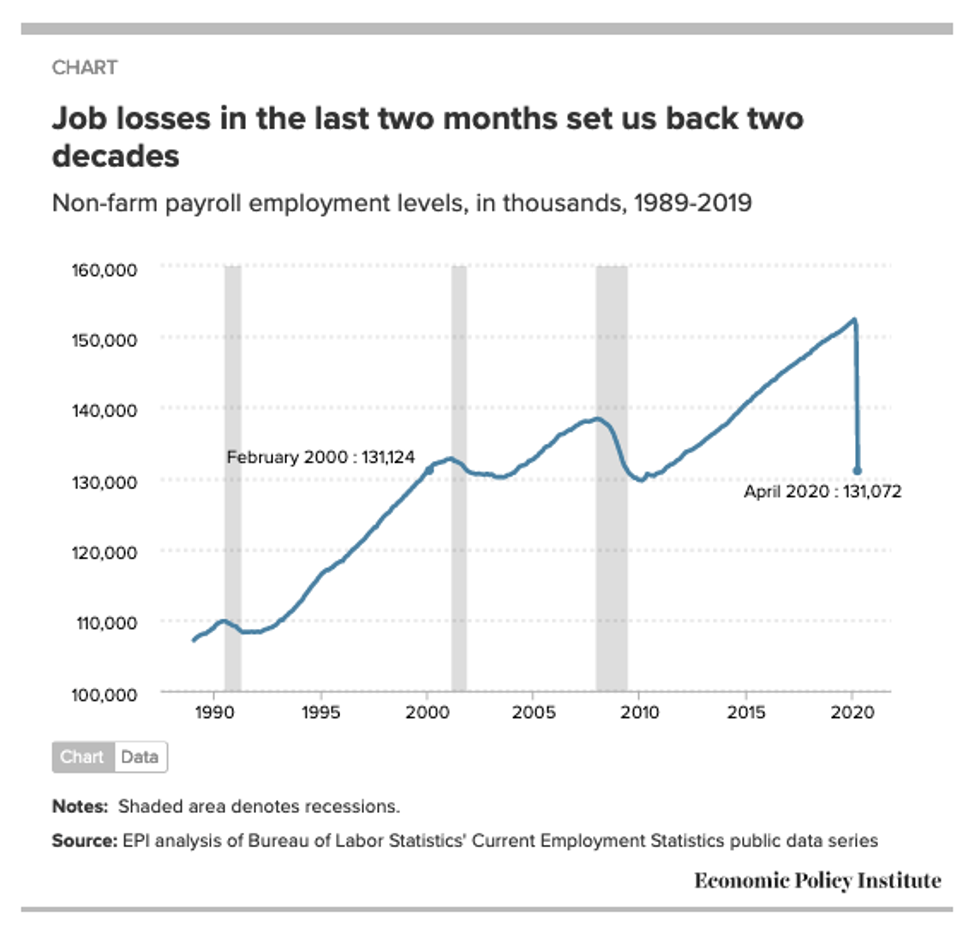

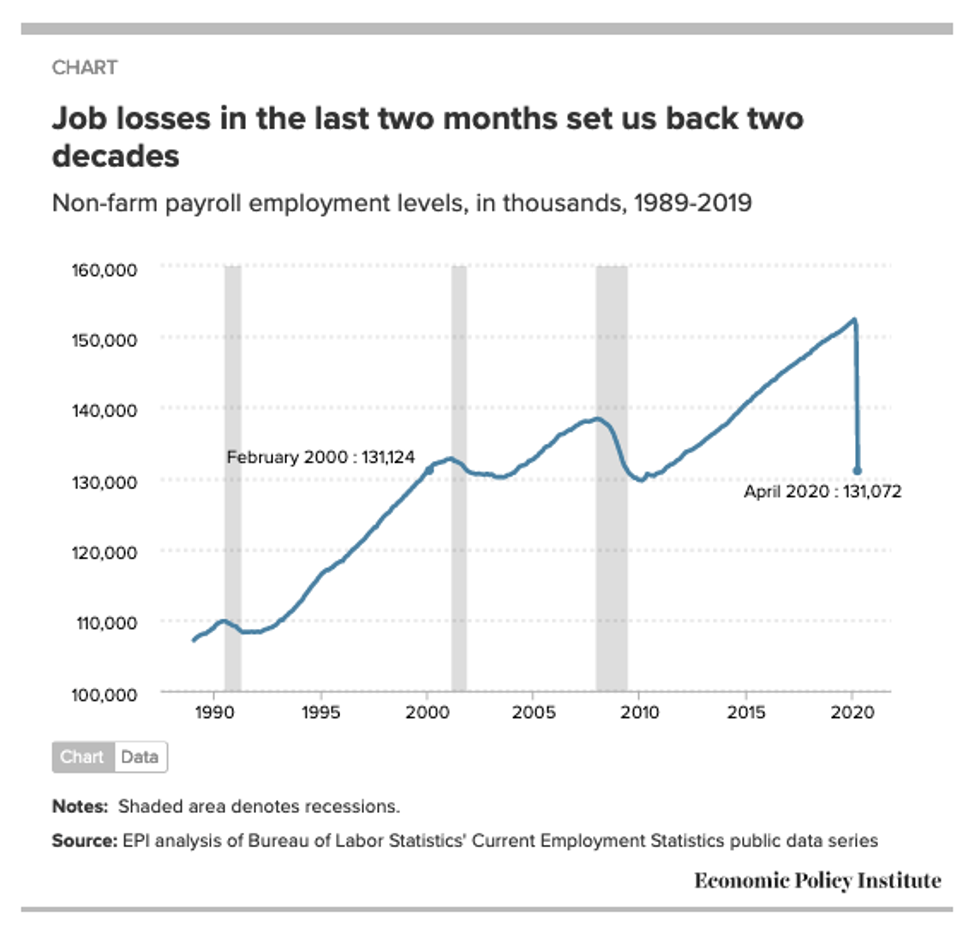

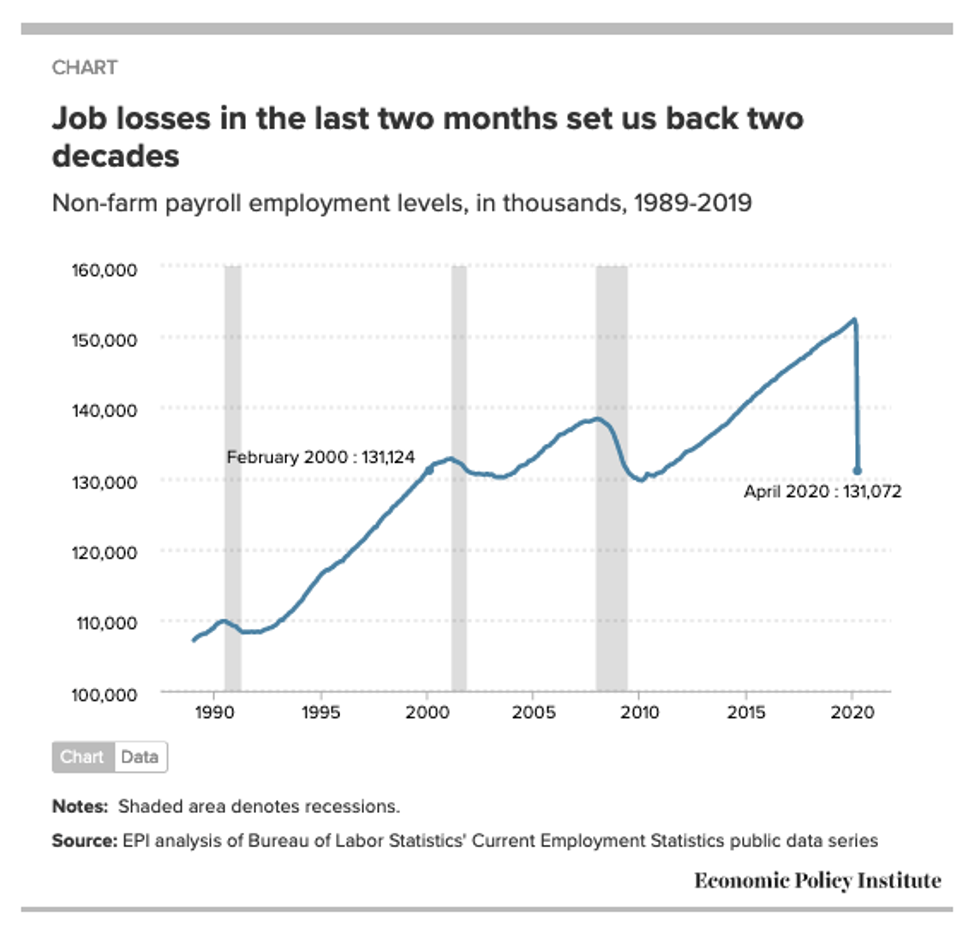

After a sharp fall in March, payroll employment dropped like a rock in April. I struggle to even put into words how large this drop is. It's as if all the gains in employment since 2000 were wiped out. Total job losses over the last two months would fill all 30 currently empty Major League Baseball stadiums 16 times over. It's as if all the jobs in all of the states beginning with the letter "M" simply disappeared in the last month. That's all the jobs in Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, and Montana combined.

The job losses in April were far more widespread than the job losses in March. There were acute losses in leisure and hospitality (-7.7 million), education and health services (-2.5 million), professional and business services (-2.1 million), retail trade (-2.1 million), manufacturing (-1.3 million), and other services (-1.3 million).

Women workers continue to bear a larger share of job losses in the COVID-19 labor market. In April, women suffered 54.9% of total job losses. Women represented 50.0% of payroll employment in February, but represented 55.0% of job losses over the last two months.

Production and non-supervisory workers--who represent roughly the bottom 82% of all workers, when lined up by earnings--experienced the lion's share of job losses in April. Total private-sector jobs fell by 19.5 million while production and non-supervisory jobs fell by 18.1 million, far greater than proportionate to their shares of jobs in the economy. This means that the losses to managers and supervisory workers were relatively small in comparison.

The unemployment rate rose faster than ever before, hitting 14.7% in April. Today's unemployment rate is far in excess of the high water mark hit at the worst of the Great Recession, which topped out at 10.0% in 2009. It is the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression. However, 78.3% of unemployed workers report being on temporary layoff, which is a positive sign when we get on the other side of the health crisis.

April's unemployment rate is still an underestimate of the actual number of unemployed workers. It would be higher if all the people who lost their jobs had actually remained in the labor force. A large share of workers who have lost their jobs will very likely not be counted in the official unemployment rate because they won't be actively looking for work. Given the nature of the pandemic, where we are all being told to stay away from work and all non-essential public activity, many laid-off workers will make the rational decision not to search for work until they get the all-clear from public health authorities. Those job losses will show up as a drop in the labor force, but will not show up as a spike in the unemployment rate. If they were included, the unemployment rate would have hit 19.0% in April.

Furthermore, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has warned us that many workers that they would have otherwise counted as unemployed will be reported as "employed but not at work." If we count these workers as unemployed along with those who left the labor force, the unemployment rate would have been 23.5% in April.

Aggregate weekly work hours--which captures both the job losses plus the drop in hours worked--fell off a cliff in April, dropping 14.9% in just one month.

Nominal wages grew 7.9% over the year. I must advise readers and policymakers to look away from what appears to be a silver lining to today's jobs report. At turning points in the economy, compositional effects tend to swamp any changes in wages within sectors or occupations or even workers grouped by educational attainment. While workers across the economy lost their jobs in April, many of the job losses were concentrated in lower-wage jobs. Therefore, stronger wage growth in April reflects the dropping of lower wage jobs from the total, which results in higher average wages for the remaining jobs, and what appears to be faster overall growth, but not driven by people getting meaningful raises.

Congress needs to continue providing relief to workers and their families across the country. They need to extend expanded unemployment insurance until the labor market has sufficiently recovered and provide a huge amount of aid to state and local governments. The next relief package should also include worker protections, a paycheck guarantee, invest in our democracy, provide relief to the postal service, and make significant investments in testing and contact tracing.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

After a sharp fall in March, payroll employment dropped like a rock in April. I struggle to even put into words how large this drop is. It's as if all the gains in employment since 2000 were wiped out. Total job losses over the last two months would fill all 30 currently empty Major League Baseball stadiums 16 times over. It's as if all the jobs in all of the states beginning with the letter "M" simply disappeared in the last month. That's all the jobs in Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, and Montana combined.

The job losses in April were far more widespread than the job losses in March. There were acute losses in leisure and hospitality (-7.7 million), education and health services (-2.5 million), professional and business services (-2.1 million), retail trade (-2.1 million), manufacturing (-1.3 million), and other services (-1.3 million).

Women workers continue to bear a larger share of job losses in the COVID-19 labor market. In April, women suffered 54.9% of total job losses. Women represented 50.0% of payroll employment in February, but represented 55.0% of job losses over the last two months.

Production and non-supervisory workers--who represent roughly the bottom 82% of all workers, when lined up by earnings--experienced the lion's share of job losses in April. Total private-sector jobs fell by 19.5 million while production and non-supervisory jobs fell by 18.1 million, far greater than proportionate to their shares of jobs in the economy. This means that the losses to managers and supervisory workers were relatively small in comparison.

The unemployment rate rose faster than ever before, hitting 14.7% in April. Today's unemployment rate is far in excess of the high water mark hit at the worst of the Great Recession, which topped out at 10.0% in 2009. It is the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression. However, 78.3% of unemployed workers report being on temporary layoff, which is a positive sign when we get on the other side of the health crisis.

April's unemployment rate is still an underestimate of the actual number of unemployed workers. It would be higher if all the people who lost their jobs had actually remained in the labor force. A large share of workers who have lost their jobs will very likely not be counted in the official unemployment rate because they won't be actively looking for work. Given the nature of the pandemic, where we are all being told to stay away from work and all non-essential public activity, many laid-off workers will make the rational decision not to search for work until they get the all-clear from public health authorities. Those job losses will show up as a drop in the labor force, but will not show up as a spike in the unemployment rate. If they were included, the unemployment rate would have hit 19.0% in April.

Furthermore, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has warned us that many workers that they would have otherwise counted as unemployed will be reported as "employed but not at work." If we count these workers as unemployed along with those who left the labor force, the unemployment rate would have been 23.5% in April.

Aggregate weekly work hours--which captures both the job losses plus the drop in hours worked--fell off a cliff in April, dropping 14.9% in just one month.

Nominal wages grew 7.9% over the year. I must advise readers and policymakers to look away from what appears to be a silver lining to today's jobs report. At turning points in the economy, compositional effects tend to swamp any changes in wages within sectors or occupations or even workers grouped by educational attainment. While workers across the economy lost their jobs in April, many of the job losses were concentrated in lower-wage jobs. Therefore, stronger wage growth in April reflects the dropping of lower wage jobs from the total, which results in higher average wages for the remaining jobs, and what appears to be faster overall growth, but not driven by people getting meaningful raises.

Congress needs to continue providing relief to workers and their families across the country. They need to extend expanded unemployment insurance until the labor market has sufficiently recovered and provide a huge amount of aid to state and local governments. The next relief package should also include worker protections, a paycheck guarantee, invest in our democracy, provide relief to the postal service, and make significant investments in testing and contact tracing.

After a sharp fall in March, payroll employment dropped like a rock in April. I struggle to even put into words how large this drop is. It's as if all the gains in employment since 2000 were wiped out. Total job losses over the last two months would fill all 30 currently empty Major League Baseball stadiums 16 times over. It's as if all the jobs in all of the states beginning with the letter "M" simply disappeared in the last month. That's all the jobs in Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, and Montana combined.

The job losses in April were far more widespread than the job losses in March. There were acute losses in leisure and hospitality (-7.7 million), education and health services (-2.5 million), professional and business services (-2.1 million), retail trade (-2.1 million), manufacturing (-1.3 million), and other services (-1.3 million).

Women workers continue to bear a larger share of job losses in the COVID-19 labor market. In April, women suffered 54.9% of total job losses. Women represented 50.0% of payroll employment in February, but represented 55.0% of job losses over the last two months.

Production and non-supervisory workers--who represent roughly the bottom 82% of all workers, when lined up by earnings--experienced the lion's share of job losses in April. Total private-sector jobs fell by 19.5 million while production and non-supervisory jobs fell by 18.1 million, far greater than proportionate to their shares of jobs in the economy. This means that the losses to managers and supervisory workers were relatively small in comparison.

The unemployment rate rose faster than ever before, hitting 14.7% in April. Today's unemployment rate is far in excess of the high water mark hit at the worst of the Great Recession, which topped out at 10.0% in 2009. It is the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression. However, 78.3% of unemployed workers report being on temporary layoff, which is a positive sign when we get on the other side of the health crisis.

April's unemployment rate is still an underestimate of the actual number of unemployed workers. It would be higher if all the people who lost their jobs had actually remained in the labor force. A large share of workers who have lost their jobs will very likely not be counted in the official unemployment rate because they won't be actively looking for work. Given the nature of the pandemic, where we are all being told to stay away from work and all non-essential public activity, many laid-off workers will make the rational decision not to search for work until they get the all-clear from public health authorities. Those job losses will show up as a drop in the labor force, but will not show up as a spike in the unemployment rate. If they were included, the unemployment rate would have hit 19.0% in April.

Furthermore, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has warned us that many workers that they would have otherwise counted as unemployed will be reported as "employed but not at work." If we count these workers as unemployed along with those who left the labor force, the unemployment rate would have been 23.5% in April.

Aggregate weekly work hours--which captures both the job losses plus the drop in hours worked--fell off a cliff in April, dropping 14.9% in just one month.

Nominal wages grew 7.9% over the year. I must advise readers and policymakers to look away from what appears to be a silver lining to today's jobs report. At turning points in the economy, compositional effects tend to swamp any changes in wages within sectors or occupations or even workers grouped by educational attainment. While workers across the economy lost their jobs in April, many of the job losses were concentrated in lower-wage jobs. Therefore, stronger wage growth in April reflects the dropping of lower wage jobs from the total, which results in higher average wages for the remaining jobs, and what appears to be faster overall growth, but not driven by people getting meaningful raises.

Congress needs to continue providing relief to workers and their families across the country. They need to extend expanded unemployment insurance until the labor market has sufficiently recovered and provide a huge amount of aid to state and local governments. The next relief package should also include worker protections, a paycheck guarantee, invest in our democracy, provide relief to the postal service, and make significant investments in testing and contact tracing.