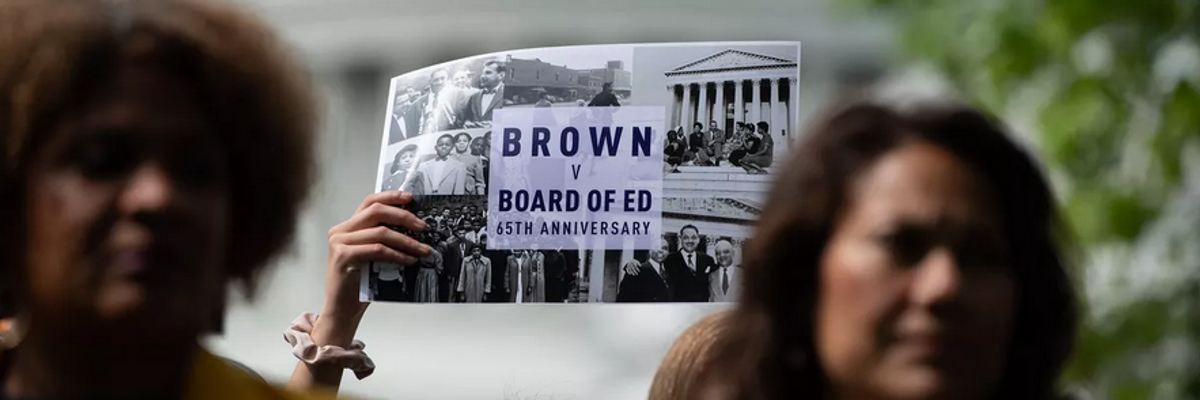

Sunday, May 17, marked the 66th anniversary of the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision, Brown vs. the Board of Education. The Brown decision addressed consolidated issues from four different cases -- in Kansas, South Carolina, Delaware and Virginia--involving racial segregation.

The unanimous opinion of the Court was written by Earl Warren, Republican President Dwight Eisenhower's newly appointed chief justice. The Court declared that forced segregation of children in public schools violated the due process clause of the 14th Amendment and was, therefore, unconstitutional.

But Brown is about much more than schools. It was a death knell for legal apartheid in the United States, originally sanctioned in the Dred Scott decision of 1857, and codified in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. The Brown decision established unequivocally that African Americans had equal rights in America.

While the Supreme Court decides what the law is, it can't actually enforce the law. The Court's decisions often follow public opinion rather than lead it. But its decisions can empower and legitimatize, for better or for worse.

In 1896, the Supreme Court took up Plessy v. Ferguson, which involved a dispute over segregated train transportation in Louisiana. Homer Plessy, a fair-skinned African American man who could "pass" for white, purchased a first-class ticket and had taken his seat in a whites-only train car. When he refused to take a seat in the "dirt car" reserved for blacks, he was arrested and jailed.

The Supreme Court ruled that separate accommodations on trains and in other facilities was legal, provided that the accommodations were substantially equal. Hence, the legal apartheid of race and white supremacy in America was born. The decision was met with a stirring dissent by Justice John Marshall Harlan, a former slave owner, who argued that the "arbitrary separation of citizens on the basis of race is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with ... the equality before the law established by the Constitution."

Harlan was a lonely voice at the time. The infamous "Compromise of 1877" had already taken place, withdrawing federal troops from the South and bringing Reconstruction to an end. The Civil Rights cases of 1883 had effectively nullified the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and the terrorist campaigns of the Ku Klux Klan effectively squelched the brief era of freedom in the South after the Civil War.

In one context, Plessy was a case about race and public transportation. In another, more troubling context, the Plessy case symbolized something more onerous. The Supreme Court had given legal authority to the Jim Crow laws in the South. Segregated facilities--that could never, in fact, be equal--became the rule, rather than the exception.

When Chief Justice Warren issued the unanimous opinion of the Court in Brown, he wrote that "...in the field of public education the doctrine of separate but equal has no place," as segregated schools are "inherently unequal." His ruling stripped segregation of its constitutional authority and immoral sanction. And it applied to much more than public schools.

The growing civil rights movement, propelled by the decision, pushed to integrate all public facilities. In 1955, Rosa Parks refused to take a seat in the back of a bus. Eventually, with passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the law revived the intent of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments. These amendments, passed in the wake of the Civil War, declared that all had the right to equal justice under the law, and that these rights applied to the states, as well.

We now face a renewed resistance to equal justice and equal rights. In the 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder, the Court, by a 5-4 vote (with five right-wing justices in the majority), gutted the Voting Rights Act. The scandalous decision by Chief Justice John Roberts overturned the re-authorization of the Act by Congress, arguing that the country "has changed" and that racial discrimination in voting was no longer a problem in the South.

The shortsighted ruling in Shelby has had broad implications. Across the South, and increasingly in the rest of the country, Republicans passed new restrictions on voting --limiting early voting, purging voter rolls, requiring strict voter ID laws, closing polling places--all disproportionately impacting minority voters.

Partisan gerrymandering soon followed, and today, opposition even to voting by mail has emerged. The Shelby decision has given renewed energy to the efforts to roll back advances made during the Civil Rights era.

In the midst of the current pandemic and the looming depression, the anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education has passed without much notice. But we should never forget how historic that decision was and is -- and how deplorable the decision of the "gang of five" in Shelby remains in undermining the civil rights progress that got legitimacy from Brown.

The Brown decision reminds us that the Supreme Court can be and ought to be a force for equality. We should not forget that.