"This tragedy is an opportunity." We've heard these words a lot lately.

And it's a good point, one that has been argued both adeptly and disastrously since the COVID-19 outbreak took the country by storm 10 weeks ago. From well-informed officials like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to well-intended celebrities like Gal Gadot, leaders from every sector have framed the pandemic as an opportunity to evaluate the state of American life, and possibly change our course.

This sentiment has been especially embraced by major resistance movements. Prison reform organizations are encouraging activists to use the dire situation to effect lasting policy change, including an end to solitary confinement and incarceration for people too poor to pay court fees. Union and non-union workers have harnessed their heightened visibility and "essential" status to advance key labor issues, such as income inequality and protections for low-wage workers. And climate scientists are urging lawmakers and industry leaders to view the collective response to the pandemic as a blueprint for combating global warming.

The task of interpreting the global COVID-19 crisis is happening privately as well. Many are asking, how am I being affected by this unprecedented upheaval? How have some of my most basic values and structures -- like my sense of time and space -- been morphed, renewed or lost? What are my responsibilities (and limits) as a human, citizen, community member, employee, friend, parent and partner? Should I feel angry about how the pandemic is unfolding? Or sad, anxious, hopeful, serene? Should I make a TikTok video?

Where the personal and political tasks of grappling with this catastrophic event merge is a vital space. If we can occupy this space after the shelter-in-place orders are lifted and the bare fact of our interdependence is rushed off stage, the coronavirus tragedy may in fact materialize into something substantial, something good.

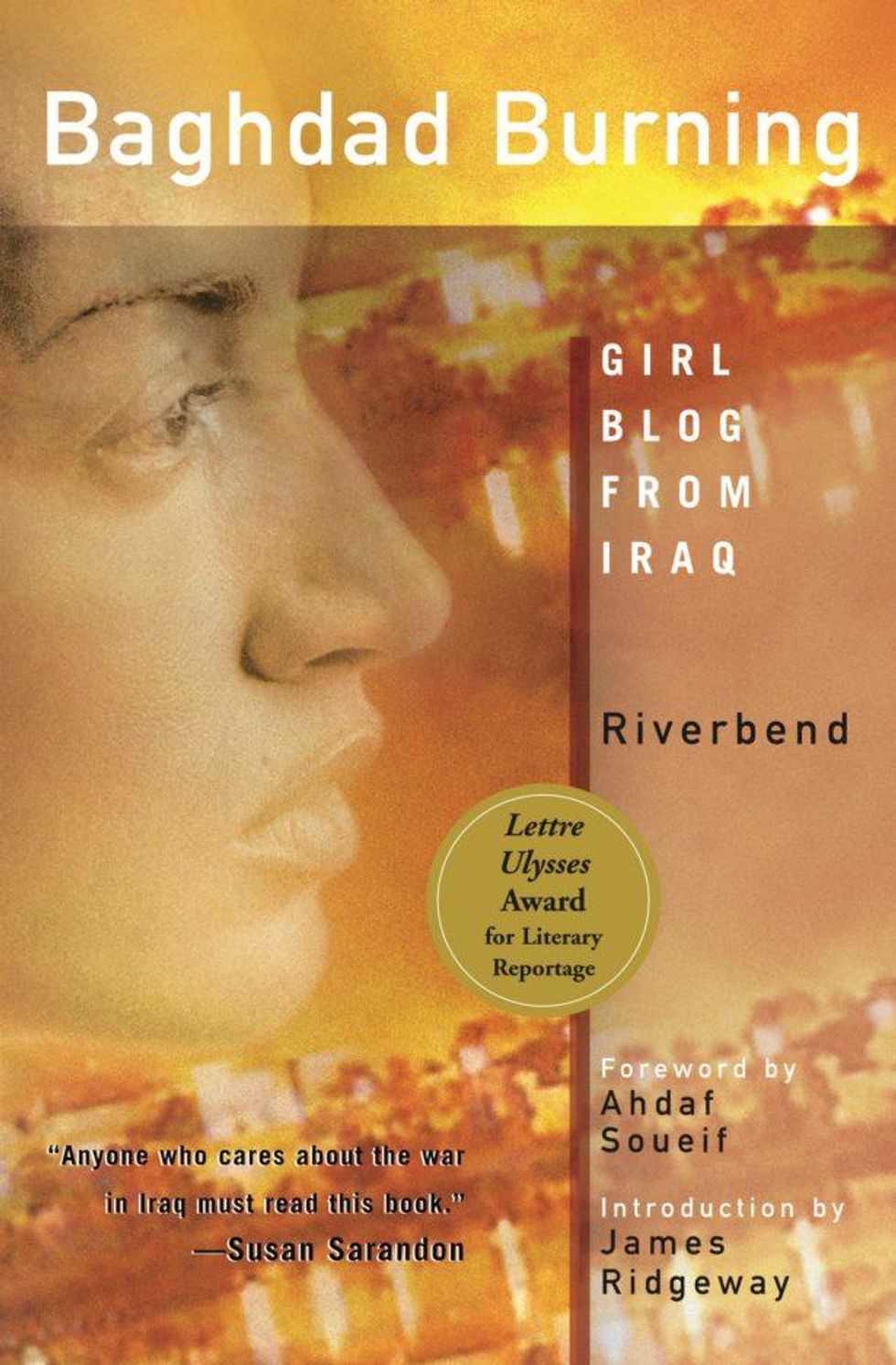

One way Americans can inhabit this crossroads in the weeks and months to come is by reading Iraqi occupation literature -- that is, literature by Iraqis about life between 2003 to 2011, when the U.S.-led Coalition Forces occupied the country. Over the last decade, a number of brilliant fiction and nonfiction books about the occupation have become available in English. Two that stand out among this emerging subgenre are "The Corpse Exhibition and Other Stories of Iraq" by the award-winning Arabic writer and filmmaker Hassan Blasim and "Baghdad Burning: Girl Blog from Iraq" by the anonymous Iraqi software engineer-turned-blogger Riverbend. Others include "The Corpse Washer" by Sinan Antoon, "Frankenstein in Baghdad" by Ahmed Saadaw, "The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq" by Dunya Mikhail, and "Baghdad Noir" edited by Samuel Shimon.

These works challenge readers to share in the experience of being occupied. Just three months ago, this experience might have been considered a subject for only niche academic audiences or, worse, written off as the plight of an unlucky pocket of the globe. But the demanding isolation of social distancing, deepening precarity caused by the shutdown of all "nonessential" sectors, and seemingly imminent threat of infection and illness have made these narratives relatable to a wider American public. The idea of being confined, indefinitely, to one shelter was inconceivable for many of us prior to the coronavirus. During the first two weeks of the shutdown, my students, who were forcibly dispersed across four continents in a matter of days, began each virtual meeting by noting how surreal and dystopian it all felt. As one New Jersey-native put it, "It's like we're in a 'Black Mirror' episode, right?"

It's also the first time since the Vietnam War that the U.S. public has been confronted with so many dead bodies, and so many lives that cannot be fully grieved. The drone footage from New York's Hart Island, where hundreds of unclaimed corpses are being buried in mass graves, crystallizes this phenomenon. It's also a dilemma shaping our daily lives in less spectacular ways: health care workers broadcasting a patient's final moments via FaceTime, essential employees beginning their shift after a brief announcement about a coworker passing, reporters updating listeners and viewers with the latest death toll.

While this is new ground for many Americans, it's old ground for many Iraqis. The mortality rate in Iraq prior to the 2003 invasion was about 5.5 people per 1,000 per year and rose to 19.8 deaths per 1,000 in the year 2006. That same year, the rate of violence rose by 51 percent in just three months, with an estimated 5,000 deaths per month. The country's medical facilities struggled to cope with the influx of bodies and the lack of capacity in their morgues, and families hired civilians to search dumps, river banks and morgues for the bodies of missing relatives.

Occupation literature is richly attentive to this history. Hassan Blasim's title story in "The Corpse Exhibition," for instance, is narrated by the leader of a fastidious murder cult, a Kafkaesque conceit that's as horrifying as it is absurd. He explains how the assassins artfully display corpses throughout the city, and these grotesque exhibitions distinguish their victims from the "random" and "stupid" deaths filling the country's mortuaries. The story dramatizes a question that underwrites the entire collection: How do we see, narrate and interpret so much death?

While Iraq now seems a distant memory, especially in the midst of our pandemic, it's a war that we barely remembered to begin with.

The virus has also laid bare the nation's deepest fault lines. Atrocious racial inequality, an impoverished commons after decades of winner-takes-all capitalism and neoliberal privatization, single-minded partisanship, a plutocratic agenda, and a fiercely polarized and disenfranchised public underwrite the devastating evolution of the pandemic in the United States. As the national death toll surpasses 100,000 -- more than eight times the American death toll in 9/11, the war in Afghanistan, Hurricane Katrina and the Iraq War combined (although still less than deaths caused by opioid overdoses and gun violence since 2018) -- these glaring failures seem bigger than ever. They have roots in the origins of this country and are also inseparable from America's 21st century wars.

Only 2.5 million Americans (0.75 percent of the population) served in Iraq or Afghanistan between 2001 and 2014. This strategically isolated and privatized military sector therefore made it possible for 99.25 percent of the country to see the Iraq War as just a "bad dream" from the start. The New York Times reported in May 2004, "The invasion of Iraq, which has already begun to seem like a bad dream in so many ways, cannot get much more nightmarish than this," and yet, "this" went on for seven more years. And it's arguably still going on. (Just this February, the Iraqi parliament pressed for American troops to "be withdrawn from all the bases." In response, the Trump administration drafted sanctions against Iraq should they expel U.S. troops.)

The conflict's less-than-real quality -- the way Iraq was always already out of focus and at arm's length -- is one reason why the U.S. government's cataclysmic "War on Terror" was met with so little resistance. It explains why, in an age of robust social unrest and political protest, the conflict remains mostly absent from public discourse, and why even my brightest and most woke students can't tell me when the Iraq War began or ended. In short, while Iraq now seems a distant memory, especially in the midst of our pandemic, it's a war that we barely remembered to begin with. Moreover, the continuing situation in Iraq and our involvement across the Middle East make grappling with this history an urgent political project. As the writer Derek Miller argues, "The story of Iraq has ended, we feel, because we see nothing but repetition. But the story is not over. If anything, it is only the beginning."

Hassan Blasim's "The Corpse Exhibition" and Riverbend's "Baghdad Burning" are emblems of Iraqi-authored occupation literature. They are also valuable resources for drawing connections between the so-called War on Terror and America's current crisis. Each book represents a very different genre and medium. "The Corpse Exhibition" is an experimental collection of surreal, poetic and absurd short stories that mostly serve as allegories to the occupation. "Baghdad Burning," on the other hand, is a collection pieced together from a civilian blog that gained worldwide attention for chronicling daily life in Iraq's occupied capital from December 2003 to September 2004. It's telling, therefore, that these books share a number of defining features.

One of those features is the trope of Iraq's occupied civilians as ghosts, jinnis (supernatural spirits in Arabic mythology), or divided subjects -- liminal figures existing at the threshold between life and death, waking and dreaming, human and non-human, here and there. "Baghdad Burning" opens about five months after the American invasion with the pseudonymous author resolving to blog about daily life under the occupation because, as she writes, "I guess I've got nothing to lose." She quickly distinguishes herself from the "third world" Muslim women of the Western imagination. A university-educated engineer with a music collection ranging from Britney Spears to Nirvana, the 24-year-old had a budding career and busy social life prior to May 2003. She was free to move -- solo and hijabless -- around the city as she pleased. All that changed with the occupation.

Riverbend chronicles the shift from her pre- to post-invasion life in details that are equal parts humorous and harrowing, raw and cerebral. She notes how the American troops carry out conventional forms of combat: killing, wounding and torturing Iraqi people. (Abu Ghraib, she affirms, was a watershed moment). But more often, she attends to the military's more abstract and indirect engagement with those living in Baghdad. The occupying troops ravage the country's infrastructure -- electricity, water, gas and other basic services are constant problems -- and they spread themselves everywhere in order to control and reconstruct the city. They also conduct patrols and raids that operate along the same logic as terrorism: surprise, chaos, asymmetry and mistrust. These strategies seem to facilitate the Islamic State's domination and violence, a phenomenon that Riverbend highlights in her interrogative about the sounds that wake her at night: "What can it be? A burglar? A gang of looters? An attack? A bomb? Or maybe just an American midnight raid."

"Baghdad Burning" also gives readers a window into the psychological and social effects of the occupation. This form of militarism makes Riverbend and other Iraqis feel like they exist in an alternate reality, outside recognizable social and structural forms, like politics and time. When Donald Rumsfeld visits the country in September 2003, Riverbend observes how he moves through Baghdad "safe in the middle of all his bodyguards." Rumsfeld's movement is a particularly cruel and distressing element of the occupation for Riverbend, whose own mobility had become radically restricted (by that point, she couldn't leave home without a head covering and male relative). "It's awful to see him strutting all over the place ... like he's here to add insult to injury ... you know, just in case anyone forgets we're in an occupied country." The young Baghdadi woman's experience of the perverse and unassailable distance between herself and the U.S. Secretary of Defense typifies the occupier-occupied relationship in "Baghdad Burning," a dynamic that leads Riverbend to the hopeless feeling that "everything now belongs to someone else ... I can't see the future at this point."

"The Corpse Exhibition" homes in on the effects of living under an occupying force as well. However, Hassan Blasim goes a step further and presents the occupation as a fatal or near-fatal form of governance for Iraqi civilians. Blasim was born in Baghdad in 1973 and fled to Finland in 2004, where he still resides. While Blasim primarily evokes the American occupation of Iraq, which began after the 2003 invasion, the region's long history of legal and structural subjugation is never out of focus. Multiple tales blur the line between the country's past, present and future, situating stony-eyed allusions to the Iraq Petroleum Company, Baathist regime, Iran-Iraq war and American occupation side by side.

The short story "The Hole," for instance, opens with the narrator getting food from his old shop, which he was forced to close after the invasion. Three masked gunmen appear, and while running to escape the indistinct threat, the narrator falls into a hole occupied by an aged and spectral Baghdadi man. Rather than a sense of causality, historicity, materiality and so on, life in the hole is characterized by randomness, boundlessness and immateriality. It is an "endless chain," a game based on "a series of experiments" whose inventors "couldn't control the game, which rolls ceaselessly on and on through the curves of time." The narrator is unable to apprehend the game's inventors and terms and, thus, achieve movement and an ending -- quite literally to die or escape the hole. So he becomes a "ghost" or a "jinni" like the old Baghdadi man before him, and the story ends with a new subject falling into the hole. It's an ending that emphatically resists narrative resolution and confronts readers with the experience of being stuck in a seemingly endless cycle of subjugation and dispossession.

This idea comes to a head in the final short story, "The Nightmares of Carlos Fuentes." Salim Abdul Husain is an Iraqi man who works for the municipality cleaning up the aftermath of explosions: "chickens, fruits and vegetables and some people," he notes with grim frankness on the opening page. Salim is granted asylum in Holland, changes his name to Carlos Fuentes (wholly unaware of the irony), and dedicates himself to disavowing his Iraqi self and past. But uncontrollable nightmares threaten his painstaking efforts to forge a new identity as a Dutch national. Trapped between his dreaming and waking life, Fuentes resolves to "put an end" to his divided state by "sweeping out all the rubbish of the unconscious" -- a claim that evokes his job cleaning up the aftermath of explosions in Iraq and connects the Sunni immigrant's psychic suffering to the uniquely indirect violence involved in the occupation. Fuentes studies conscious dreaming in order to gain control of his sleeping life and, by extension, the seemingly random death and violence that defined his life in occupied Iraq.

At last, Fuentes finds himself in a state of conscious dreaming. He enters a building in central Baghdad and shoots every man, woman and child "with skill and precision." Upon reaching the top floor, Fuentes meets Salim -- or rather, himself. He aims his rifle at Salim's head and then, panicked, "let out a resounding scream and started to spray Salim Abdul Husain with bullets, but Salim jumped out the window and not a single bullet hit him." "Carlos Fuentes," on the other hand, "was dead on the pavement, and a pool of blood was spreading slowly under his head." Much like the narrator turned jinni in "The Hole," only the unreal, dreaming subject survives in Blasim's closing story. Life in occupied Iraq, in other words, leaves the Iraqi people neither alive nor dead, forced to exist at the threshold of existence.

The pandemic is an opportunity for Americans to connect with the stories of the millions of Iraqis we have refused to look squarely in the face.

The vision of ordinary citizens forced into an unlivable situation, as offered up by "The Corpse Exhibition" and "Baghdad Burning," distinguishes Iraqi occupation literature, and it points to one grounds for a renewed peace movement. By seeing America's 21st century wars from the perspective of the "other"--a perspective displaced by Hollywood's faceless terrorists and the post-Cold War military's "zero death" doctrine--we can begin to resist what Barack Obama called the nation's "permanent war footing." Put differently, once we see the occupation as a real nightmare for real Iraqi people, rather than just a bad dream for Americans, we can begin to re-politicize the strategically depoliticized activity of war.

At times, dissent has emerged from unlikely quarters. After being made Trump's first Secretary of Defense, James "Mad Dog" Mattis -- the four-star Marine general who commanded U.S. troops in the Gulf War, Afghanistan and the Iraq War--proved that he wasn't the hawkish isolationist of Trump's imagination. Mattis resigned in December 2018, citing "policy differences," while Trump, of course, replied that he "fired" him. At a conference last spring, Mattis advocated for greater diplomacy in the country's approach to radical terrorism in the Middle East. He also made a plea to the international community that echoes his ongoing counsel to the American people: "We need to hold fast to each other. We need to engage more with each other."

The COVID-19 tragedy is an opportunity for just this. The pandemic is an opportunity for Americans to connect with the stories of the millions of Iraqis we have refused to look squarely in the face. It's an opportunity for us to engage with those who have persisted in a global system that seems hell bent on destroying them and to begin accounting for their reality. In June 2004, after a long week of scorching temperatures, outrageous government appointments, and a border teeming with Iraqi asylum seekers, Riverbend concluded, "People are simply tired of waiting for normality and security. It was difficult enough during the year ... this summer promises to be a particularly long one."

As Americans now look forward to a particularly long summer, activists, artists, educators and public figures would be wise to read, teach and promote Iraqi occupation literature. The pandemic -- our struggle with the unprecedented -- has primed us to identify with the struggle of the real and fictional Iraqis who inhabit this subgenre. Without seeing the story of contemporary Iraq as our story, we cannot remedy the devastation unleashed on the region or intervene to stop America's "permanent" war machine -- a system which relies upon a civilian population who passively consents to violence against non-Western people. And we cannot transform American militarism into what it should be: a central political issue of our time.