New York Times photo (6/2/20) of police arresting protesters on 42nd Street after curfew. (Photo: Chang W. Lee/New York Times)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

New York Times photo (6/2/20) of police arresting protesters on 42nd Street after curfew. (Photo: Chang W. Lee/New York Times)

For well over a week, uprisings have surged throughout the country in pursuit of justice for George Floyd, a black man who was killed on May 25 by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, as well as other victims of racist US state violence. As a maneuver to suppress these protests, more than 200 municipal US governments, including those of New York City, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, instituted daily curfews.

The curfews, which began on May 30, are quite clearly a punitive measure meant to throttle protesters' ability to demonstrate without fear of arrest or assault from police. This is far from the first time curfews have been deployed to stymie anti-racist dissent: Since at least the 1940s, governments have routinely implemented them during popular revolts throughout the United States, including those in Watts in 1965 and Ferguson in 2014. Yet, according to leading media narratives, the curfews aren't deliberate measures of cruelty that infringe upon fundamental rights; they're the hard but necessary choice that dedicated city officials must make in the interest of public safety.

NBC News (5/30/20) published a summary of curfews in major US cities, characterizing local governments as "bracing" for another night of protests. In a story headlined "Curfews Follow Days of Looting and Demonstrations," the Washington Post (6/1/20) described the restrictions as "a measure pandemic-weary government officials hoped would deter violence and stanch the damage to their battered cities." Who, exactly, was responsible for that "violence"--police armed with rubber-jacketed bullets, teargas, flash grenades, pepper bombs and batons, or protesters equipped with none of those weapons--wasn't specified.

The New York Times (6/2/20) portrayed New York City's first curfew since World War II as "a solution of some kind to a level of pandemonium on city streets that longtime New York leaders said had no recent parallel." (As with the Post story, any role police played in said "pandemonium" went unaddressed.) The Times lauded the decision, which "did not come easily," as one of careful consideration, appearing to find far more value in making unpopular choices that benefit police than in heeding the urgent demands of an aggrieved public.

The number of city and state officials and police departments cited in these stories far outnumbered that of civilians affected by these curfews. NBC News published quotes from 12 mayors, one governor and one police department, while the Washington Post solely cited "officials," including five mayors and one police chief. Meanwhile, the New York Times spoke to current and former police--among them Bill Bratton, an architect of stop-and-frisk with a history of violence against protesters--as well as elected officials and a nonprofit executive. Only one source acknowledged the potential dangers of the curfews for late-shift workers, especially those who are black. Worse, none of the reports included commentary from protesters or workers the curfews could imperil.

This, in part, explains why media failed to capture the inequities these curfews enabled. After curfews were instated, arrests soared in Atlanta, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New York City and elsewhere, while police violently targeted those out after curfew, in some cases forcibly removing drivers and passengers from cars in order to arrest them. Compounding this, city governments repeatedly gave residents virtually no notice when issuing curfew notifications, further endangering those who were demonstrating, or merely outside, at the time of the announcements.

Meanwhile, workers in commercial food delivery and healthcare were unable to work or return home from work, while food pantry organizers were prohibited from feeding those in need--despite the fact that the work of both groups has been deemed "essential" during the pandemic. Public transit closed with the enactment of the curfews, stranding riders while leaving them vulnerable to arrest and abuse for simply existing in public after an hour chosen at the whim of government.

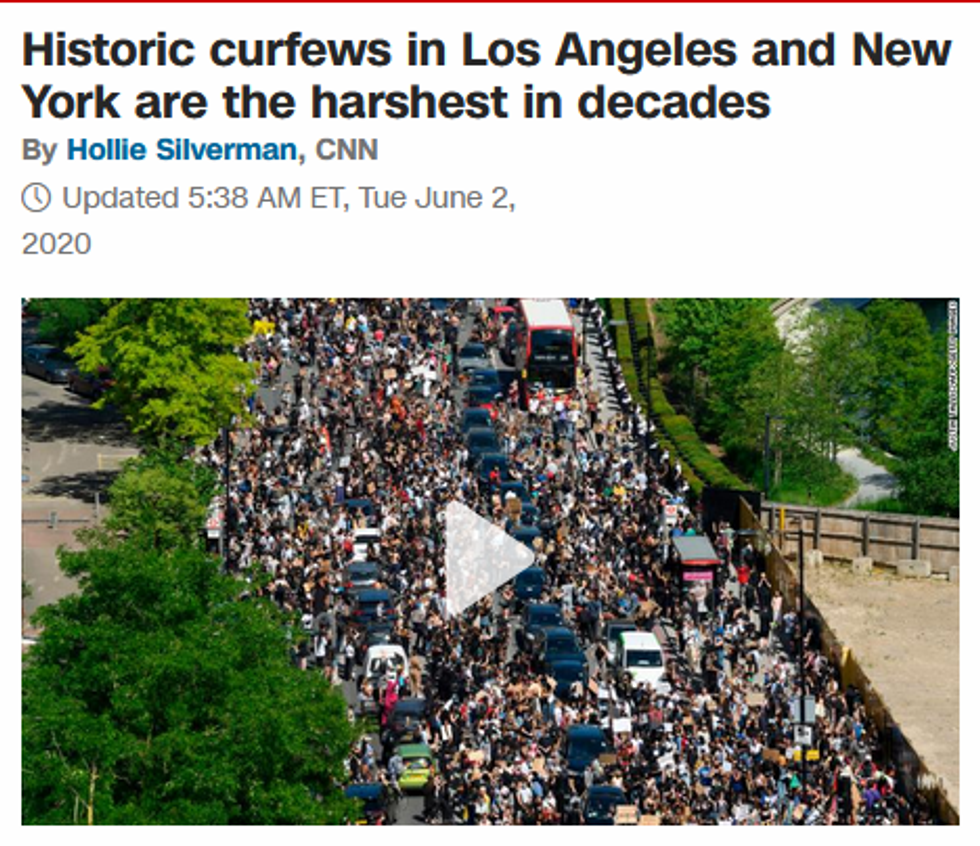

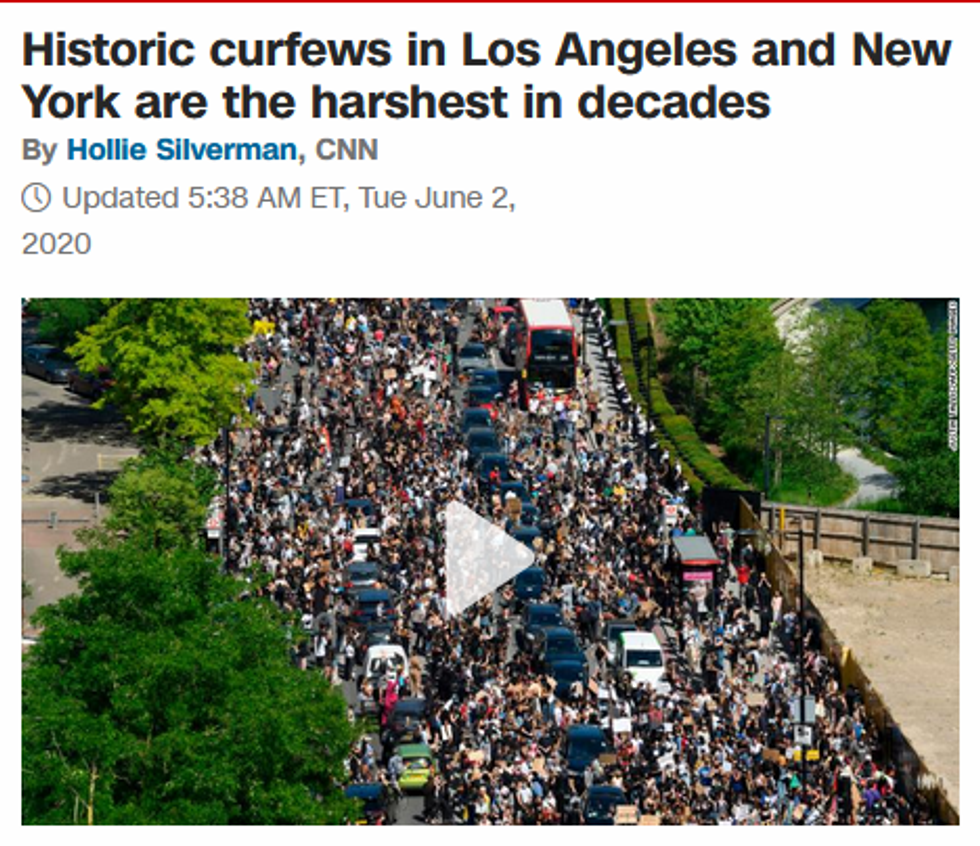

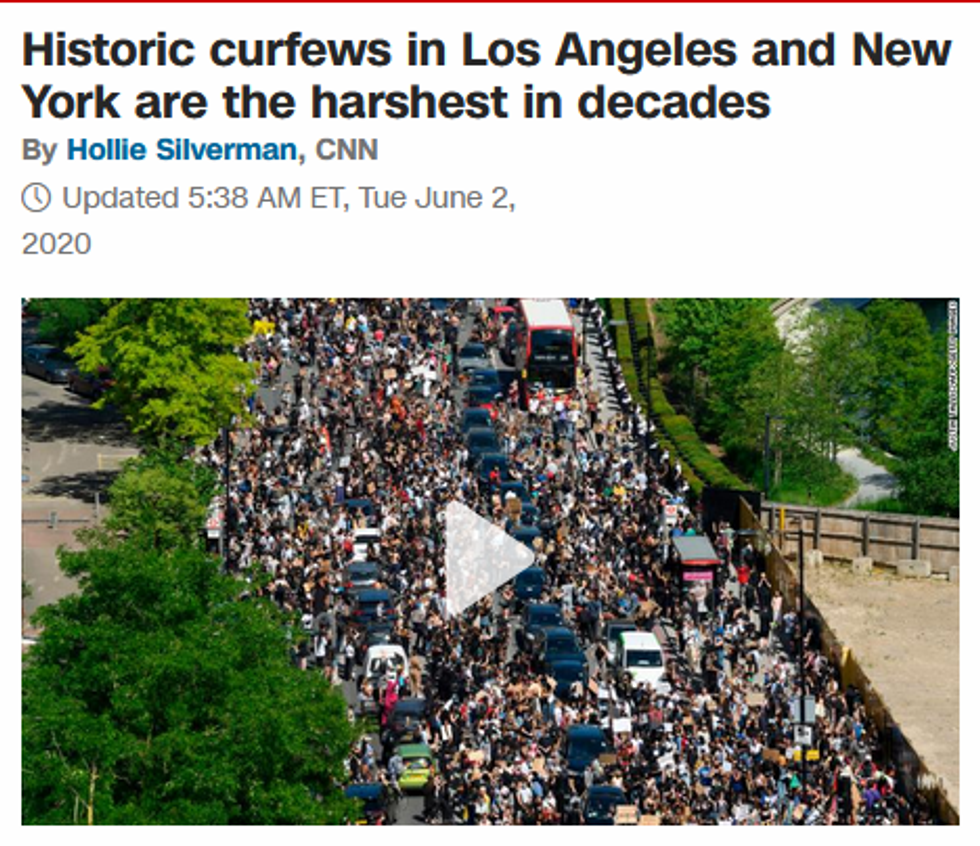

Even when media acknowledge that the curfews are, at the very least, contestable, there's little to no focus on the barbarism of those policies. CNN (6/2/20) conceded that the curfews in Los Angeles and New York were "the harshest in decades," only to rely on the perspectives of LAPD Chief Michael Moore, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio. Vox (5/31/20) and Wired (6/4/20) addressed the heightened risks people of color face when curfews are imposed. Their primary concern, however, was whether curfews would "work"--a word tacitly defined by police and the governments that buttress them--and whether curfews could "pit residents against law enforcement," a question that ignores the very reason for the uprisings.

There are signs that curfews are dwindling, if just temporarily. After threatening to extend curfews until protests stopped, the city of Los Angeles revoked its particularly draconian curfew, which lasted for at least 12 hours for multiple days. (It's likely that this was partially a result of an emergency lawsuit from the ACLU and Black Lives Matter, though a number of other factors, including pressure from businesses and police PR campaigns, may have contributed.) Other cities have taken similar measures.

Still, the city's largest newspaper framed the softening as a testament to police and governments' success at quelling crowds. In a story announcing the curfew cancellation, the Los Angeles Times (6/4/20) patronizingly presented the change as a reward to a populace that had engaged in "peaceful" protest, publishing Los Angeles County Supervisor Janice Hahn's remark that curfews aren't "needed anymore"--as though a policy criminalizing antiracist protest was ever "needed." A recent USA Today headline (6/4/20) echoed this sentiment: "In CA: In Some Cities, Nighttime Curfew Deemed No Longer Necessary."

As curfews elsewhere continue and police resume use of horrific, even deadly tactics, news media will have a choice: Use historical context and information from protesters on the ground to convey what's truly at stake, or continue to defer to the deceptive pablum of police departments and mayoral offices. Given major publications' patterns of pro-police PR (see FAIR.org, 9/2/15, 10/10/18, 1/15/20, 5/28/20), it's not hard to imagine what that choice will be.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

For well over a week, uprisings have surged throughout the country in pursuit of justice for George Floyd, a black man who was killed on May 25 by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, as well as other victims of racist US state violence. As a maneuver to suppress these protests, more than 200 municipal US governments, including those of New York City, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, instituted daily curfews.

The curfews, which began on May 30, are quite clearly a punitive measure meant to throttle protesters' ability to demonstrate without fear of arrest or assault from police. This is far from the first time curfews have been deployed to stymie anti-racist dissent: Since at least the 1940s, governments have routinely implemented them during popular revolts throughout the United States, including those in Watts in 1965 and Ferguson in 2014. Yet, according to leading media narratives, the curfews aren't deliberate measures of cruelty that infringe upon fundamental rights; they're the hard but necessary choice that dedicated city officials must make in the interest of public safety.

NBC News (5/30/20) published a summary of curfews in major US cities, characterizing local governments as "bracing" for another night of protests. In a story headlined "Curfews Follow Days of Looting and Demonstrations," the Washington Post (6/1/20) described the restrictions as "a measure pandemic-weary government officials hoped would deter violence and stanch the damage to their battered cities." Who, exactly, was responsible for that "violence"--police armed with rubber-jacketed bullets, teargas, flash grenades, pepper bombs and batons, or protesters equipped with none of those weapons--wasn't specified.

The New York Times (6/2/20) portrayed New York City's first curfew since World War II as "a solution of some kind to a level of pandemonium on city streets that longtime New York leaders said had no recent parallel." (As with the Post story, any role police played in said "pandemonium" went unaddressed.) The Times lauded the decision, which "did not come easily," as one of careful consideration, appearing to find far more value in making unpopular choices that benefit police than in heeding the urgent demands of an aggrieved public.

The number of city and state officials and police departments cited in these stories far outnumbered that of civilians affected by these curfews. NBC News published quotes from 12 mayors, one governor and one police department, while the Washington Post solely cited "officials," including five mayors and one police chief. Meanwhile, the New York Times spoke to current and former police--among them Bill Bratton, an architect of stop-and-frisk with a history of violence against protesters--as well as elected officials and a nonprofit executive. Only one source acknowledged the potential dangers of the curfews for late-shift workers, especially those who are black. Worse, none of the reports included commentary from protesters or workers the curfews could imperil.

This, in part, explains why media failed to capture the inequities these curfews enabled. After curfews were instated, arrests soared in Atlanta, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New York City and elsewhere, while police violently targeted those out after curfew, in some cases forcibly removing drivers and passengers from cars in order to arrest them. Compounding this, city governments repeatedly gave residents virtually no notice when issuing curfew notifications, further endangering those who were demonstrating, or merely outside, at the time of the announcements.

Meanwhile, workers in commercial food delivery and healthcare were unable to work or return home from work, while food pantry organizers were prohibited from feeding those in need--despite the fact that the work of both groups has been deemed "essential" during the pandemic. Public transit closed with the enactment of the curfews, stranding riders while leaving them vulnerable to arrest and abuse for simply existing in public after an hour chosen at the whim of government.

Even when media acknowledge that the curfews are, at the very least, contestable, there's little to no focus on the barbarism of those policies. CNN (6/2/20) conceded that the curfews in Los Angeles and New York were "the harshest in decades," only to rely on the perspectives of LAPD Chief Michael Moore, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio. Vox (5/31/20) and Wired (6/4/20) addressed the heightened risks people of color face when curfews are imposed. Their primary concern, however, was whether curfews would "work"--a word tacitly defined by police and the governments that buttress them--and whether curfews could "pit residents against law enforcement," a question that ignores the very reason for the uprisings.

There are signs that curfews are dwindling, if just temporarily. After threatening to extend curfews until protests stopped, the city of Los Angeles revoked its particularly draconian curfew, which lasted for at least 12 hours for multiple days. (It's likely that this was partially a result of an emergency lawsuit from the ACLU and Black Lives Matter, though a number of other factors, including pressure from businesses and police PR campaigns, may have contributed.) Other cities have taken similar measures.

Still, the city's largest newspaper framed the softening as a testament to police and governments' success at quelling crowds. In a story announcing the curfew cancellation, the Los Angeles Times (6/4/20) patronizingly presented the change as a reward to a populace that had engaged in "peaceful" protest, publishing Los Angeles County Supervisor Janice Hahn's remark that curfews aren't "needed anymore"--as though a policy criminalizing antiracist protest was ever "needed." A recent USA Today headline (6/4/20) echoed this sentiment: "In CA: In Some Cities, Nighttime Curfew Deemed No Longer Necessary."

As curfews elsewhere continue and police resume use of horrific, even deadly tactics, news media will have a choice: Use historical context and information from protesters on the ground to convey what's truly at stake, or continue to defer to the deceptive pablum of police departments and mayoral offices. Given major publications' patterns of pro-police PR (see FAIR.org, 9/2/15, 10/10/18, 1/15/20, 5/28/20), it's not hard to imagine what that choice will be.

For well over a week, uprisings have surged throughout the country in pursuit of justice for George Floyd, a black man who was killed on May 25 by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, as well as other victims of racist US state violence. As a maneuver to suppress these protests, more than 200 municipal US governments, including those of New York City, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, instituted daily curfews.

The curfews, which began on May 30, are quite clearly a punitive measure meant to throttle protesters' ability to demonstrate without fear of arrest or assault from police. This is far from the first time curfews have been deployed to stymie anti-racist dissent: Since at least the 1940s, governments have routinely implemented them during popular revolts throughout the United States, including those in Watts in 1965 and Ferguson in 2014. Yet, according to leading media narratives, the curfews aren't deliberate measures of cruelty that infringe upon fundamental rights; they're the hard but necessary choice that dedicated city officials must make in the interest of public safety.

NBC News (5/30/20) published a summary of curfews in major US cities, characterizing local governments as "bracing" for another night of protests. In a story headlined "Curfews Follow Days of Looting and Demonstrations," the Washington Post (6/1/20) described the restrictions as "a measure pandemic-weary government officials hoped would deter violence and stanch the damage to their battered cities." Who, exactly, was responsible for that "violence"--police armed with rubber-jacketed bullets, teargas, flash grenades, pepper bombs and batons, or protesters equipped with none of those weapons--wasn't specified.

The New York Times (6/2/20) portrayed New York City's first curfew since World War II as "a solution of some kind to a level of pandemonium on city streets that longtime New York leaders said had no recent parallel." (As with the Post story, any role police played in said "pandemonium" went unaddressed.) The Times lauded the decision, which "did not come easily," as one of careful consideration, appearing to find far more value in making unpopular choices that benefit police than in heeding the urgent demands of an aggrieved public.

The number of city and state officials and police departments cited in these stories far outnumbered that of civilians affected by these curfews. NBC News published quotes from 12 mayors, one governor and one police department, while the Washington Post solely cited "officials," including five mayors and one police chief. Meanwhile, the New York Times spoke to current and former police--among them Bill Bratton, an architect of stop-and-frisk with a history of violence against protesters--as well as elected officials and a nonprofit executive. Only one source acknowledged the potential dangers of the curfews for late-shift workers, especially those who are black. Worse, none of the reports included commentary from protesters or workers the curfews could imperil.

This, in part, explains why media failed to capture the inequities these curfews enabled. After curfews were instated, arrests soared in Atlanta, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New York City and elsewhere, while police violently targeted those out after curfew, in some cases forcibly removing drivers and passengers from cars in order to arrest them. Compounding this, city governments repeatedly gave residents virtually no notice when issuing curfew notifications, further endangering those who were demonstrating, or merely outside, at the time of the announcements.

Meanwhile, workers in commercial food delivery and healthcare were unable to work or return home from work, while food pantry organizers were prohibited from feeding those in need--despite the fact that the work of both groups has been deemed "essential" during the pandemic. Public transit closed with the enactment of the curfews, stranding riders while leaving them vulnerable to arrest and abuse for simply existing in public after an hour chosen at the whim of government.

Even when media acknowledge that the curfews are, at the very least, contestable, there's little to no focus on the barbarism of those policies. CNN (6/2/20) conceded that the curfews in Los Angeles and New York were "the harshest in decades," only to rely on the perspectives of LAPD Chief Michael Moore, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio. Vox (5/31/20) and Wired (6/4/20) addressed the heightened risks people of color face when curfews are imposed. Their primary concern, however, was whether curfews would "work"--a word tacitly defined by police and the governments that buttress them--and whether curfews could "pit residents against law enforcement," a question that ignores the very reason for the uprisings.

There are signs that curfews are dwindling, if just temporarily. After threatening to extend curfews until protests stopped, the city of Los Angeles revoked its particularly draconian curfew, which lasted for at least 12 hours for multiple days. (It's likely that this was partially a result of an emergency lawsuit from the ACLU and Black Lives Matter, though a number of other factors, including pressure from businesses and police PR campaigns, may have contributed.) Other cities have taken similar measures.

Still, the city's largest newspaper framed the softening as a testament to police and governments' success at quelling crowds. In a story announcing the curfew cancellation, the Los Angeles Times (6/4/20) patronizingly presented the change as a reward to a populace that had engaged in "peaceful" protest, publishing Los Angeles County Supervisor Janice Hahn's remark that curfews aren't "needed anymore"--as though a policy criminalizing antiracist protest was ever "needed." A recent USA Today headline (6/4/20) echoed this sentiment: "In CA: In Some Cities, Nighttime Curfew Deemed No Longer Necessary."

As curfews elsewhere continue and police resume use of horrific, even deadly tactics, news media will have a choice: Use historical context and information from protesters on the ground to convey what's truly at stake, or continue to defer to the deceptive pablum of police departments and mayoral offices. Given major publications' patterns of pro-police PR (see FAIR.org, 9/2/15, 10/10/18, 1/15/20, 5/28/20), it's not hard to imagine what that choice will be.