Last week, the International Energy Agency (IEA) published a new Special Report on Sustainable Recovery. The IEA, which calls itself the "world's most authoritative source of energy-market analysis," set out to guide governments towards short-term energy investments that could address the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic while advancing long-term sustainability and climate goals.

While the IEA has led with welcome rhetoric about the importance of putting clean energy at the heart of stimulus efforts, the actual contents of the report fall short on climate ambition - a chronic problem for the IEA. The report completely ignores the reality that staying within 1.5 degrees Celsius (degC) of global warming is key to a sustainable recovery.

If the IEA is serious about helping governments sustainably tackle interlocking economic and climate crises, they have one more chance to prove it with their data: by making a 1.5-aligned energy pathway central to the 2020 World Energy Outlook (WEO).

This matters because climate scientists say we need to halve carbon emissions within this decade to have a reasonable chance of staying within 1.5degC. Governments need clear guidance on the near-term energy investments that would catalyze the pace and scale of transformation required to do that. As we unpack in greater detail below, the IEA's new report does not deliver it.

While the IEA ultimately comes to some positive conclusions - namely, that energy efficiency and renewable energy investments are the best recovery tools - it lacks a cohesive climate lens and promotes false solutions that would prolong fossil fuels.

From a broader perspective, the Sustainable Recovery report is another example of an IEA that is fundamentally at odds with itself, leading to a lack of coherence in its analysis:

- The "good" IEA recognizes that to retain public credibility it must integrate responses to the climate crisis into its communications and analysis. This is the IEA that says governments must put "clean energy at the heart" of stimulus packages.

- The "bad" IEA remains beholden to incumbent industries like fossil fuels and, as a result, avoids recommending necessary climate solutions that would fundamentally threaten their existence. This is the IEA that, the week after releasing its new report, lobbied the European Union to carve out loopholes for fossil gas in its definition of sustainable investments.

To prove itself fit for purpose in a time of climate emergency, the IEA needs to model an energy transformation aligned with 1.5degC. But then the IEA would have to acknowledge the need for a rapid phase-out of fossil fuels, putting it at odds with the industries it was created to protect and has aligned with for decades. Hence, the internal conflict.

This fall is the next key opportunity for the IEA to finally ditch its fossil fuel bias and live up to its rhetoric on climate. If the IEA is serious about its commitment to sustainable recovery and a stable climate, it will develop a robust 1.5-aligned scenario and put that at the center of its annual World Energy Outlook.

If you're into the weeds, read on for more in-depth analysis of the contents and relevance of the Sustainable Recovery report, in three parts:

- Forgetting 1.5degC is key to sustainability

- Ignoring half the solution: Phasing out fossil fuels

- Sending conflicting messages

Forgetting 1.5degC is key to sustainability

As the IEA was developing its report, more than 60 top climate scientists, business and civil society leaders, and investors sent a letter to IEA director Dr. Fatih Birol urging him to seize this "historic opportunity" and map out "robust recovery pathways aligned with 1.5oC." Over the past year, leaders in the climate community have been ratcheting up pressure on the IEA to upgrade its scenarios to align with this limit, recognizing the IEA's outsized influence in steering government and private investment decisions worldwide.

As recapped above, the IEA ignored these demands again. The Sustainable Recovery report does not even mention the critical 1.5-degree limit enshrined in the Paris Agreement. The IEA suggests that, taken together, its three-year, USD 3 trillion recovery plan would lower annual energy-related CO2 emissions by nearly 3.5 gigatonnes (Gt) by 2025, compared to business as usual. Astoundingly, the IEA never clarifies what baseline it is comparing that against.

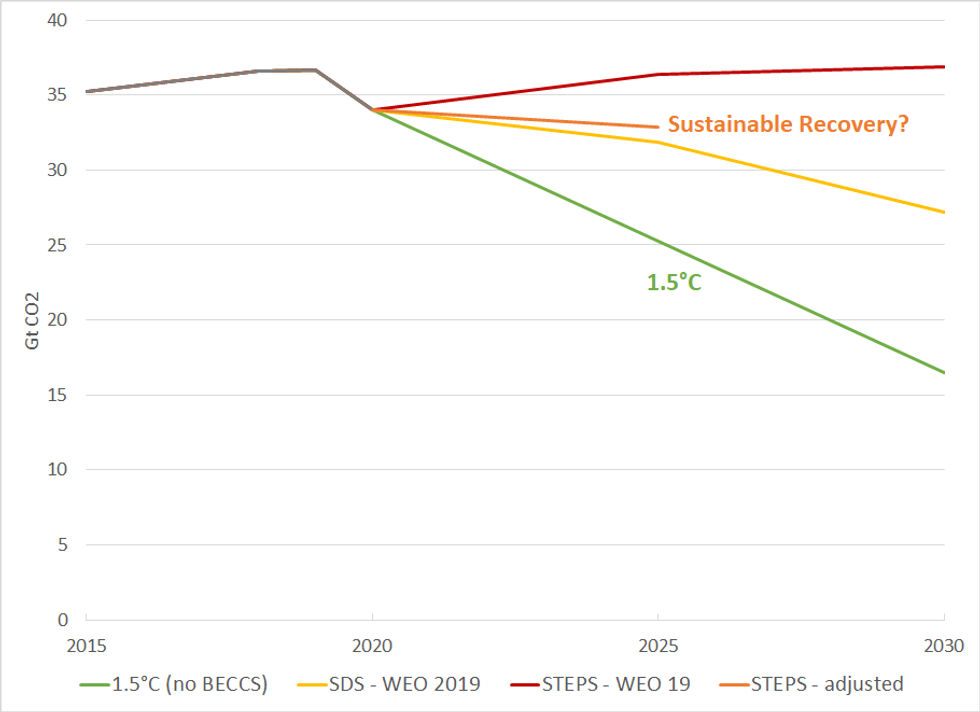

The chart below shows where that 3.5 Gt of avoided CO2 would get us in 2025 if we use the baseline of the IEA's 2019 Stated Energy Policies Scenario (STEPS), which is a scenario based on policies governments have already committed to enact. The Sustainable Recovery plan would, in this case, lead to a "structural decline" in emissions, as the IEA has emphasized. But that slight decline would leave the world far off track from the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels needed to halve carbon pollution this decade to stay within 1.5degC. The plan doesn't even put us fully on track with the IEA's 2019 Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS), a below 2degC scenario.

IEA Sustainable Recovery Plan, compared to 1.5degC pathway*

*The P1 pathway from the IPCC SR15 is shown, as it avoids reliance on bioenergy with carbon capture and storage. We add projected cement and industrial process emissions from the IEA's Faster Transitions Scenario to WEO 2019 scenarios, for comparability with IPCC pathways. If the Sustainable Recovery Plan is compared to the baseline of the IEA's Current Policies Scenario, then the resulting 2025 CO2 emissions would be higher than shown.

The goal posts matter and the stakes are high. The potential consequences of a hotter-than-1.5degC world - more extreme sea level rise, greater crop failure and hunger, obliterated ecosystems, and millions more people at risk of displacement and death - hardly qualify as "sustainable."

The coming wave of trillions of dollars of investments could make or break the world's ability to stay within 1.5degC of warming and avoid greater degrees of human suffering and devastation. Yet governments will find no guidance from the IEA on how to design a recovery package equipped to do that.

Ignoring half the solution: Phasing out fossil fuels

As noted above, the IEA report does point governments in some positive directions on clean energy - there are elements of the "good IEA."

The IEA essentially reaffirms conclusions well tread by many reports before it: that energy efficiency, solar, and wind power can create more jobs than fossil fuels while reducing carbon pollution. The IEA summarizes that wind and solar PV deployment "are two of the power technologies that most merit government support in many countries," and suggests that energy efficiency should receive a full one-third of energy-related recovery investments.

However, effectively tackling the climate crisis is not simply a question of addition, or ramping up new clean technologies. It's also a challenge of subtraction--winding down the industries whose pollution is causing the problem.

As the letter sent to the IEA put it last month, "Effective stimulus measures will ensure that new clean energy replaces fossil fuels, rather than adding to them."

In this respect, the IEA recovery report is wholly lacking.

In the report's introduction, the IEA states that its focus in relation to the "fuels" sector is to "make the production and use of fuels more sustainable." By "sustainable," the IEA means the oil and gas industry produces fewer emissions per barrel of fuel extracted, even as the IEA's own data show the extraction process itself accounts for just 15 percent of global carbon emissions from oil and gas.

From this narrow lens, the IEA limits its recommendations on oil- and gas-related recovery measures to support for reducing methane emissions and expanding the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. This is typical of the "bad IEA" - cherry picking "solutions" that are relatively innocuous for the industry to implement (if they care to), but are completely ill-equipped to drive the rapid phase-out of oil and gas the world needs.

Oil and gas use needs to decline by around 4 percent, on average, each year of this decade to have a reasonable chance of staying within 1.5 degrees. That's according to the most precautionary of four pathways featured in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's landmark 2018 report, the pathway that avoids reliance on unproven technologies that might fail to work. If oil companies eliminate all their methane emissions but expand their oil and gas production, total carbon emissions and global warming could keep going up.

Appropriate recovery measures for the oil and gas sector would reinforce the phase-out of the industry, while ensuring a just transition to new, high-quality careers for workers currently in the sector.

These solutions exist. But they threaten the oil and gas industry's basic business model, and the IEA neglects to consider them.

How many jobs globally could be created decommissioning fossil fuel assets and restoring polluted sites? Likely far more than would be created installing methane monitors. In fact several recent studies look at the potential for stimulus investments to create jobs closing abandoned oil and gas wells and restoring abandoned mine sites. Governments can and should support fossil fuel workers without propping up industries that need to stay in decline to secure a livable future.

Sending conflicting messages

The IEA has a long track record of choosing when and to what degree it should acknowledge climate reality, depending on who is listening.

The contents of the report recognize the need for more renewable energy, while also placating the fossil fuel industry and governments backing it by promoting piecemeal fossil fuel measures like methane reduction. In some sections, the IEA even suggests that investing in the expansion of the fossil fuel industry is a legitimate recovery option, as long as those gas or coal plants are "efficient."

The report builds a case for phasing out fossil fuel consumption subsidies. But it also proposes measures that could actually increase production subsidies, for example by expanding a tax credit in the United States that primarily pays big polluters to pump more oil out of the ground through enhanced recovery methods. This is inexcusable when production subsidies are more important for the industry's expansion prospects, and G20 governments already prop up oil, gas, and coal production with USD 77 billion dollars a year in international public finance.

The IEA undermines its own clean stimulus message not only within the contents of the report, but with companion analysis and communications that continue promoting fossil fuels.

The report does not recommend significant new fossil gas investments as part of the proposed global Sustainable Recovery Plan. Yet, in its energy review for the European Union released days later, the IEA suggests that the EU should include fossil gas in its definition of sustainable finance, undermining the efforts of European civil society leaders to ensure climate is prioritized in recovery investments.

Just days before releasing its Sustainable Recovery report, the IEA said that a recent "rebound" in oil demand and prices was "a more optimistic note" and predicted that 2021 was on pace for the "largest one-year jump ever recorded" in oil demand. Nowhere in its communications did the IEA recognize that "jump" as a bad outcome for the climate, or counter to the structural decline in emissions the IEA says should be a goal of recovery.

The IEA played this same game in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, calling for clean energy investments in stimulus measures while also calling for more investment in oil exploration and extraction. More than 10 years later, this dangerous "all of the above" approach still echoes throughout the IEA's work.

One more chance to correct the course

Ultimately, the IEA's Sustainable Recovery report itself may not be of great use to governments when it comes to the detailed design of recovery plans. It lacks the granular region- and country-specific data that makes the IEA's annual WEO publication a go-to guide for governments and investors.

Hence the IEA's second chance. Next week, IEA director Fatih Birol is convening a high-level "Clean Energy Transitions" summit with "'a grand coalition' of ministers, top energy CEOs, major investors and other key leaders from the public and private sectors from around the world." Dr. Birol should announce the IEA's commitment to reforming its 2020 WEO into a transformative tool for governments to align their energy investments with a 1.5-degree path.

The decisions made over the next three years will set our course to 2030. To be a useful authority on a sustainable recovery, the IEA needs to choose a side:

Will it stay tethered to the fossil fuel industry, producing middling analysis at odds with the severity of the climate crisis?

Or will it match the urgency of its climate rhetoric by making a 1.5-aligned energy scenario the central road map of the WEO, giving governments robust tools to ensure trillions in new investments catalyze the scale of transformation we need?