SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Activists hold signs and protest the California lockdown due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on May 01, 2020 in San Diego, California. The protesters demands included opening small businesses, churches as well as support for President Trump. (Photo: Sean M. Haffey/Getty Images)

In the second half of June, the story of the United States' coronavirus pandemic began to shift dramatically, as a massive surge in new infections took hold, particularly across states in the South and West that had previously been spared the worst of the outbreak. Media reports abruptly switched gears from declaring that reopening was proceeding with few ill effects (Reuters, 5/17/20; Tampa Bay Times, 5/28/20) to expressing alarm that health officials' warnings against lifting social distancing restrictions too soon had been proven right--a cognitive dissonance perhaps most dramatically depicted in Oregon Public Broadcasting's headline, "Oregon's COVID-19 Spike Surprises, Despite Predictions of Rising Caseloads" (6/10/20).

Increasingly, the big story has been the litany of state moves to halt or roll back reopenings: A typical roundup in the New York Times (6/26/20) included closing bars in Texas and Florida, a full stay-at-home order in California's Imperial County, and putting beaches off-limits in Miami-Dade County for the July 4th weekend.

"This is a very dangerous time," declared Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio, where new cases began rising on June 15, just over a month after the state allowed stores and businesses to reopen. "I think what is happening in Texas and Florida and several other states should be a warning to everyone."

But a warning of what? While the question of how quickly to reopen will affect potentially millions of lives, equally important is asking what science can tell us about how to reopen. Health experts point to many lessons we can learn from the pandemic experience, both in the US and elsewhere, that can help inform which activities are safest (and most necessary) to resume--a discussion that is more useful than the media's inclination toward simple debates about whether reopening is good or bad (LA Times, 5/14/20; New York Times, 5/20/20).

Among the most important conclusions:

While the coronavirus that causes Covid-19 at first seemed like an all-powerful threat that could be carried by everything from cardboard boxes to cats, public health officials have long since determined that infection is overwhelmingly via person-to-person encounters. This means that reducing face-to-face interaction time--or ensuring that it's at least conducted while wearing masks, or in outdoor or well-ventilated spaces--is key to reducing risk, as spelled out in a diagram by University of Massachusetts/Dartmouth infectious disease researcher and blogger Erin Bromage:

Infectious disease experts have attempted to reduce this equation to simple mnemonics that will be easy to remember; Tulane University epidemiologist Susan Hassig has cited "the three D's: diversity, distance and duration" (Business Insider, 6/8/20), while Ohio State's William Miller created the rhyme "time, space, people, place" (NPR, 6/23/20). These were featured in the increasingly common articles attempting to rank which activities were riskiest, including some that assigned weirdly specific point scales to behaviors for anyone wondering whether they should go bowling or for a pontoon boat ride (MLive, 6/2/20)

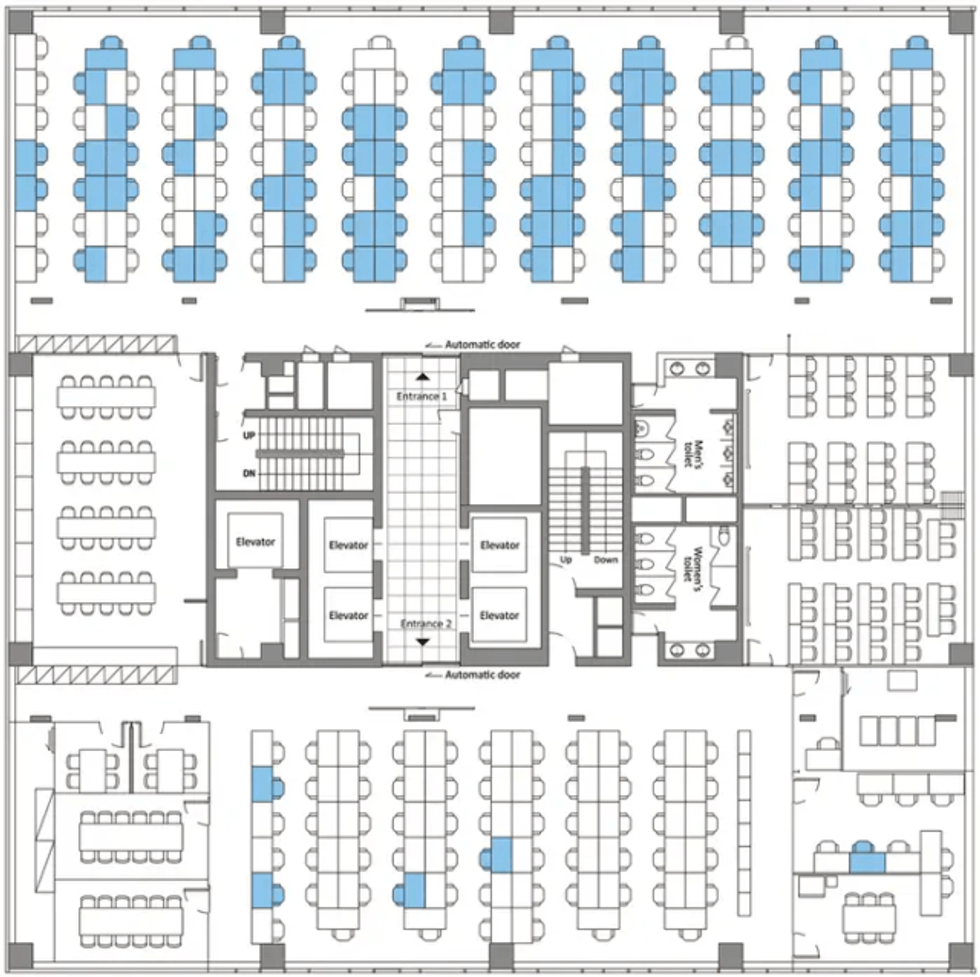

But most of those articles entirely ignored one of the most widespread reopening activities: going back to work in shared office spaces. Infectious disease experts say that offices can be the perfect petri dishes for viral spread, involving gatherings of a large number of people, indoors, for a long time, with recirculated air. As one study (Business Insider, 4/28/20) of a coronavirus outbreak at a Seoul call center showed, the virus can quickly spread across an entire floor, especially in a modern open-plan office. In fact, the call center was doubly prone to viral spread, because its workers were all talking constantly, which previous studies have found to spread respiratory droplets just as effectively as coughing (Better Humans, 4/20/20)--a warning that was heavily noted in media's coverage of the risks of chanting protestors (Washington Post, 5/31/20; Politico, 6/8/20), but notably missing from articles on the reopening of workplaces.

"They're pretty high-risk spaces," Boston University School of Public Health epidemiologist Eleanor Murray tells FAIR. "What we would like to see with offices, if people have to be there for the function of the office to work, is to keep the minimum number of people in at any given time." (She also urges consideration of the risk to office cleaning workers, who are seldom included in back-to-work safety debates.)

This is especially key, adds Tulane's Hassig, in office environments where co-workers are breathing the same air. Workers can safely unmask if they're in a private office where they can shut their door, she tells FAIR; however, "if you're in an open office space with little four-foot cubicle walls, everybody needs to be wearing masks all the time."

Yet most states have limited themselves to following CDC guidelines for reopening offices, which mandate wearing masks only when within six feet of a co-worker. But as Bromage (5/6/20) has pointed out, "Social distancing rules are really to protect you with brief exposures or outdoor exposures."

In fact, former Arizona Department of Health Services director Will Humble told Newsweek (6/9/20) that one reason his state became the nation's leader in new infections per capita was that local officials did not go beyond CDC mandates to impose "performance criteria such as required business mitigation measures, contact tracing capacity or mask-wearing." Hassig worries that the CDC's guidance may have been "far less prescriptive than they would like it to be from the scientific perspective," noting that "we've got plenty of evidence that distance is not enough if you're in a shared space with lots of people."

All of this would have been good for US workers returning to their jobs to know, but very little of it has made it into media coverage of reopenings, whether before or after the recent virus spikes. And the rare exceptions often left much to be desired: When CBS News (5/28/20) devoted time to investigating the dangers of reopening offices, it was solely in terms of whether plumbing systems left stagnant during closures could lead to the spread of Legionnaires' disease.

Because it takes at least two to three weeks for case numbers to noticeably rise in response to a change in social distancing rules, Hassig says, states should start slowly, and wait to see if numbers rise before moving on to the next stage of reopening. "If your reopening timetable is preset, that's somewhat of a folly," she says. Ideally, she says, after each change in policy, states should "wait at least three weeks to make a decision before you move on, which would mean that probably you're really looking at a month in each phase. And that is not what Texas did."

It's also not how the Texas media presented reopening plans to the public. The Austin American Statesman (4/27/20, 5/1/20) dutifully listed types of businesses that would resume operations under Gov. Greg Abbott's reopening order, but never cited any independent health officials on the risks each activity would entail. When the Dallas Morning News (4/30/20) ran answers to reader questions about the reopening, the only potential negative consequence it mentioned was whether Texans who refused to return to work could still get unemployment benefits. And the Houston Chronicle (4/30/20) declared, "No more stay-home. Just stay safe"--though the only "safety" measures it mentioned were those still being recommended by Abbott, such as wearing masks in public and limiting the size of gatherings.

The New York Times (5/1/20), meanwhile, chose to both-sides the issue with a story headlined "A Texas-Size Reopening Has Many Wondering: Too Much or Not Enough?"

In doing so, the media largely followed the lead of elected officials, who in many cases let concern over profit-and-loss statements take precedence over whether the data indicated it was safe to resume business as usual. In Ohio, state officials went so far as to allow guidelines to be written by the businesses seeking to reopen themselves (Columbus Dispatch, 6/29/20), something health experts suspect helped lead to a tripling of daily new cases in the state between June 14 and June 25.

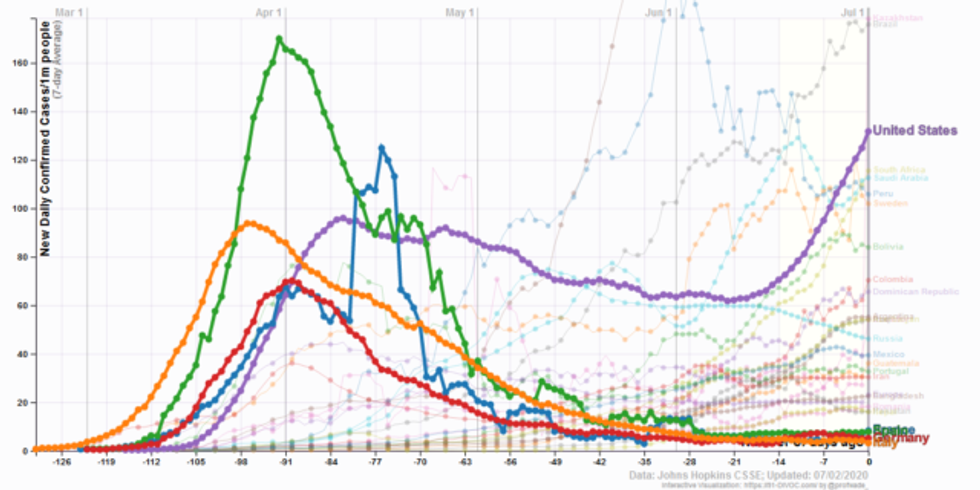

The Covid curves in many European and Asian nations that were hit the earliest and took the first and strongest action have remained low, despite reopenings in those nations: Italy, for example, once the world epicenter of the virus, currently has under three new cases per day per million residents, according to Johns Hopkins data--about half the infection rate for the least-hard-hit US state, Vermont.

Those nations, however, took very different approaches to reopening than the US. First off, they waited until case rates were much lower before reopening: When Italy first reopened restaurants on May 18, its daily new-case rate, averaged over the previous week, was 14.4 per million residents; when Florida did so on May 4, its average daily rate was 31.7 per million. "Where you start in terms of your case burden will probably wind up being one of the best predictors of how well your reopening went," says Hassig.

In addition, the measures the European nations took to get cases down that low were much stricter than those ever implemented in the US--something that was largely overlooked in rundowns of nations imposing and lifting lockdowns (New York Times, 6/10/20; CNBC, 6/25/20). "What we were doing in the US compared to what Europe was doing in terms of lockdown are completely different things," says Murray:

I have friends in France, and you had to have a permit that said what time you were allowed to go to the grocery store. So even the places in the US that did a gradual opening were already starting from a much more open place than places in Europe.

US residents can also learn from areas of their own country that have done comparatively well under reopenings. Hassig notes that New Orleans and neighboring Jefferson Parish have provided an unintentional controlled experiment--albeit "a sample of one"--in the efficacy of wearing masks: "The mayor of New Orleans made masking mandatory in indoor spaces, which empowered businesses to put up signs like 'No mask, no shoes, no shirt, no service.'"

The city, which had been an early Covid hotspot, also established a hotline to report violators, kept casinos closed longer, and kept tighter restrictions on such things as church gatherings--with the result, says Hassig, that Orleans Parish currently has less than half the new-case rate of the similarly sized Jefferson Parish. (On Monday, Jefferson Parish announced its own mandatory mask order--New Orleans Advocate, 6/29/20.)

When media outlets posit the decision facing states as balancing the economic needs with public-health needs, it not only ignores that an out-of-control pandemic would be an economic catastrophe (Guardian, 3/26/20), but overlooks another important point: In reopening, governments have a limited amount of risk they can safely spread around without losing control of an outbreak. As a result, reopening decisions don't just impact public health and the economy now--they also could end up undermining your ability to reopen other things down the road.

"It's not 'open' or 'shut'--there's a whole spectrum in between," says Murray. "We need to be thinking about what are the high-priority things that we need to reopen from a functioning point of view, and not an enjoyment point of view."

If the goal is to prevent the kind of explosive surge in Covid cases that many states saw in March and April--and which are now being repeated in new hotspots in June and July--that means picking and choosing carefully, not just which activities are the safest, but which are the most urgent for a functioning society--which, it bears emphasizing, is not the same thing as what's best for businesses' bottom lines.

"We need to be getting dentists' offices open and getting childcare open and getting elective medical treatment open; bars are not as important," advises Murray. "It may be that we have to give up on some of those things to allow the risks that some of these other activities take."

That's a discussion that will require informed public debate on the conditions of reopening, from what should stay closed to whether to require masks. It's a debate that will be much easier if the media spends less time on who is "winning" or "losing" in the struggle to reopen, and more on why people are getting infected--and how they could not be.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

In the second half of June, the story of the United States' coronavirus pandemic began to shift dramatically, as a massive surge in new infections took hold, particularly across states in the South and West that had previously been spared the worst of the outbreak. Media reports abruptly switched gears from declaring that reopening was proceeding with few ill effects (Reuters, 5/17/20; Tampa Bay Times, 5/28/20) to expressing alarm that health officials' warnings against lifting social distancing restrictions too soon had been proven right--a cognitive dissonance perhaps most dramatically depicted in Oregon Public Broadcasting's headline, "Oregon's COVID-19 Spike Surprises, Despite Predictions of Rising Caseloads" (6/10/20).

Increasingly, the big story has been the litany of state moves to halt or roll back reopenings: A typical roundup in the New York Times (6/26/20) included closing bars in Texas and Florida, a full stay-at-home order in California's Imperial County, and putting beaches off-limits in Miami-Dade County for the July 4th weekend.

"This is a very dangerous time," declared Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio, where new cases began rising on June 15, just over a month after the state allowed stores and businesses to reopen. "I think what is happening in Texas and Florida and several other states should be a warning to everyone."

But a warning of what? While the question of how quickly to reopen will affect potentially millions of lives, equally important is asking what science can tell us about how to reopen. Health experts point to many lessons we can learn from the pandemic experience, both in the US and elsewhere, that can help inform which activities are safest (and most necessary) to resume--a discussion that is more useful than the media's inclination toward simple debates about whether reopening is good or bad (LA Times, 5/14/20; New York Times, 5/20/20).

Among the most important conclusions:

While the coronavirus that causes Covid-19 at first seemed like an all-powerful threat that could be carried by everything from cardboard boxes to cats, public health officials have long since determined that infection is overwhelmingly via person-to-person encounters. This means that reducing face-to-face interaction time--or ensuring that it's at least conducted while wearing masks, or in outdoor or well-ventilated spaces--is key to reducing risk, as spelled out in a diagram by University of Massachusetts/Dartmouth infectious disease researcher and blogger Erin Bromage:

Infectious disease experts have attempted to reduce this equation to simple mnemonics that will be easy to remember; Tulane University epidemiologist Susan Hassig has cited "the three D's: diversity, distance and duration" (Business Insider, 6/8/20), while Ohio State's William Miller created the rhyme "time, space, people, place" (NPR, 6/23/20). These were featured in the increasingly common articles attempting to rank which activities were riskiest, including some that assigned weirdly specific point scales to behaviors for anyone wondering whether they should go bowling or for a pontoon boat ride (MLive, 6/2/20)

But most of those articles entirely ignored one of the most widespread reopening activities: going back to work in shared office spaces. Infectious disease experts say that offices can be the perfect petri dishes for viral spread, involving gatherings of a large number of people, indoors, for a long time, with recirculated air. As one study (Business Insider, 4/28/20) of a coronavirus outbreak at a Seoul call center showed, the virus can quickly spread across an entire floor, especially in a modern open-plan office. In fact, the call center was doubly prone to viral spread, because its workers were all talking constantly, which previous studies have found to spread respiratory droplets just as effectively as coughing (Better Humans, 4/20/20)--a warning that was heavily noted in media's coverage of the risks of chanting protestors (Washington Post, 5/31/20; Politico, 6/8/20), but notably missing from articles on the reopening of workplaces.

"They're pretty high-risk spaces," Boston University School of Public Health epidemiologist Eleanor Murray tells FAIR. "What we would like to see with offices, if people have to be there for the function of the office to work, is to keep the minimum number of people in at any given time." (She also urges consideration of the risk to office cleaning workers, who are seldom included in back-to-work safety debates.)

This is especially key, adds Tulane's Hassig, in office environments where co-workers are breathing the same air. Workers can safely unmask if they're in a private office where they can shut their door, she tells FAIR; however, "if you're in an open office space with little four-foot cubicle walls, everybody needs to be wearing masks all the time."

Yet most states have limited themselves to following CDC guidelines for reopening offices, which mandate wearing masks only when within six feet of a co-worker. But as Bromage (5/6/20) has pointed out, "Social distancing rules are really to protect you with brief exposures or outdoor exposures."

In fact, former Arizona Department of Health Services director Will Humble told Newsweek (6/9/20) that one reason his state became the nation's leader in new infections per capita was that local officials did not go beyond CDC mandates to impose "performance criteria such as required business mitigation measures, contact tracing capacity or mask-wearing." Hassig worries that the CDC's guidance may have been "far less prescriptive than they would like it to be from the scientific perspective," noting that "we've got plenty of evidence that distance is not enough if you're in a shared space with lots of people."

All of this would have been good for US workers returning to their jobs to know, but very little of it has made it into media coverage of reopenings, whether before or after the recent virus spikes. And the rare exceptions often left much to be desired: When CBS News (5/28/20) devoted time to investigating the dangers of reopening offices, it was solely in terms of whether plumbing systems left stagnant during closures could lead to the spread of Legionnaires' disease.

Because it takes at least two to three weeks for case numbers to noticeably rise in response to a change in social distancing rules, Hassig says, states should start slowly, and wait to see if numbers rise before moving on to the next stage of reopening. "If your reopening timetable is preset, that's somewhat of a folly," she says. Ideally, she says, after each change in policy, states should "wait at least three weeks to make a decision before you move on, which would mean that probably you're really looking at a month in each phase. And that is not what Texas did."

It's also not how the Texas media presented reopening plans to the public. The Austin American Statesman (4/27/20, 5/1/20) dutifully listed types of businesses that would resume operations under Gov. Greg Abbott's reopening order, but never cited any independent health officials on the risks each activity would entail. When the Dallas Morning News (4/30/20) ran answers to reader questions about the reopening, the only potential negative consequence it mentioned was whether Texans who refused to return to work could still get unemployment benefits. And the Houston Chronicle (4/30/20) declared, "No more stay-home. Just stay safe"--though the only "safety" measures it mentioned were those still being recommended by Abbott, such as wearing masks in public and limiting the size of gatherings.

The New York Times (5/1/20), meanwhile, chose to both-sides the issue with a story headlined "A Texas-Size Reopening Has Many Wondering: Too Much or Not Enough?"

In doing so, the media largely followed the lead of elected officials, who in many cases let concern over profit-and-loss statements take precedence over whether the data indicated it was safe to resume business as usual. In Ohio, state officials went so far as to allow guidelines to be written by the businesses seeking to reopen themselves (Columbus Dispatch, 6/29/20), something health experts suspect helped lead to a tripling of daily new cases in the state between June 14 and June 25.

The Covid curves in many European and Asian nations that were hit the earliest and took the first and strongest action have remained low, despite reopenings in those nations: Italy, for example, once the world epicenter of the virus, currently has under three new cases per day per million residents, according to Johns Hopkins data--about half the infection rate for the least-hard-hit US state, Vermont.

Those nations, however, took very different approaches to reopening than the US. First off, they waited until case rates were much lower before reopening: When Italy first reopened restaurants on May 18, its daily new-case rate, averaged over the previous week, was 14.4 per million residents; when Florida did so on May 4, its average daily rate was 31.7 per million. "Where you start in terms of your case burden will probably wind up being one of the best predictors of how well your reopening went," says Hassig.

In addition, the measures the European nations took to get cases down that low were much stricter than those ever implemented in the US--something that was largely overlooked in rundowns of nations imposing and lifting lockdowns (New York Times, 6/10/20; CNBC, 6/25/20). "What we were doing in the US compared to what Europe was doing in terms of lockdown are completely different things," says Murray:

I have friends in France, and you had to have a permit that said what time you were allowed to go to the grocery store. So even the places in the US that did a gradual opening were already starting from a much more open place than places in Europe.

US residents can also learn from areas of their own country that have done comparatively well under reopenings. Hassig notes that New Orleans and neighboring Jefferson Parish have provided an unintentional controlled experiment--albeit "a sample of one"--in the efficacy of wearing masks: "The mayor of New Orleans made masking mandatory in indoor spaces, which empowered businesses to put up signs like 'No mask, no shoes, no shirt, no service.'"

The city, which had been an early Covid hotspot, also established a hotline to report violators, kept casinos closed longer, and kept tighter restrictions on such things as church gatherings--with the result, says Hassig, that Orleans Parish currently has less than half the new-case rate of the similarly sized Jefferson Parish. (On Monday, Jefferson Parish announced its own mandatory mask order--New Orleans Advocate, 6/29/20.)

When media outlets posit the decision facing states as balancing the economic needs with public-health needs, it not only ignores that an out-of-control pandemic would be an economic catastrophe (Guardian, 3/26/20), but overlooks another important point: In reopening, governments have a limited amount of risk they can safely spread around without losing control of an outbreak. As a result, reopening decisions don't just impact public health and the economy now--they also could end up undermining your ability to reopen other things down the road.

"It's not 'open' or 'shut'--there's a whole spectrum in between," says Murray. "We need to be thinking about what are the high-priority things that we need to reopen from a functioning point of view, and not an enjoyment point of view."

If the goal is to prevent the kind of explosive surge in Covid cases that many states saw in March and April--and which are now being repeated in new hotspots in June and July--that means picking and choosing carefully, not just which activities are the safest, but which are the most urgent for a functioning society--which, it bears emphasizing, is not the same thing as what's best for businesses' bottom lines.

"We need to be getting dentists' offices open and getting childcare open and getting elective medical treatment open; bars are not as important," advises Murray. "It may be that we have to give up on some of those things to allow the risks that some of these other activities take."

That's a discussion that will require informed public debate on the conditions of reopening, from what should stay closed to whether to require masks. It's a debate that will be much easier if the media spends less time on who is "winning" or "losing" in the struggle to reopen, and more on why people are getting infected--and how they could not be.

In the second half of June, the story of the United States' coronavirus pandemic began to shift dramatically, as a massive surge in new infections took hold, particularly across states in the South and West that had previously been spared the worst of the outbreak. Media reports abruptly switched gears from declaring that reopening was proceeding with few ill effects (Reuters, 5/17/20; Tampa Bay Times, 5/28/20) to expressing alarm that health officials' warnings against lifting social distancing restrictions too soon had been proven right--a cognitive dissonance perhaps most dramatically depicted in Oregon Public Broadcasting's headline, "Oregon's COVID-19 Spike Surprises, Despite Predictions of Rising Caseloads" (6/10/20).

Increasingly, the big story has been the litany of state moves to halt or roll back reopenings: A typical roundup in the New York Times (6/26/20) included closing bars in Texas and Florida, a full stay-at-home order in California's Imperial County, and putting beaches off-limits in Miami-Dade County for the July 4th weekend.

"This is a very dangerous time," declared Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio, where new cases began rising on June 15, just over a month after the state allowed stores and businesses to reopen. "I think what is happening in Texas and Florida and several other states should be a warning to everyone."

But a warning of what? While the question of how quickly to reopen will affect potentially millions of lives, equally important is asking what science can tell us about how to reopen. Health experts point to many lessons we can learn from the pandemic experience, both in the US and elsewhere, that can help inform which activities are safest (and most necessary) to resume--a discussion that is more useful than the media's inclination toward simple debates about whether reopening is good or bad (LA Times, 5/14/20; New York Times, 5/20/20).

Among the most important conclusions:

While the coronavirus that causes Covid-19 at first seemed like an all-powerful threat that could be carried by everything from cardboard boxes to cats, public health officials have long since determined that infection is overwhelmingly via person-to-person encounters. This means that reducing face-to-face interaction time--or ensuring that it's at least conducted while wearing masks, or in outdoor or well-ventilated spaces--is key to reducing risk, as spelled out in a diagram by University of Massachusetts/Dartmouth infectious disease researcher and blogger Erin Bromage:

Infectious disease experts have attempted to reduce this equation to simple mnemonics that will be easy to remember; Tulane University epidemiologist Susan Hassig has cited "the three D's: diversity, distance and duration" (Business Insider, 6/8/20), while Ohio State's William Miller created the rhyme "time, space, people, place" (NPR, 6/23/20). These were featured in the increasingly common articles attempting to rank which activities were riskiest, including some that assigned weirdly specific point scales to behaviors for anyone wondering whether they should go bowling or for a pontoon boat ride (MLive, 6/2/20)

But most of those articles entirely ignored one of the most widespread reopening activities: going back to work in shared office spaces. Infectious disease experts say that offices can be the perfect petri dishes for viral spread, involving gatherings of a large number of people, indoors, for a long time, with recirculated air. As one study (Business Insider, 4/28/20) of a coronavirus outbreak at a Seoul call center showed, the virus can quickly spread across an entire floor, especially in a modern open-plan office. In fact, the call center was doubly prone to viral spread, because its workers were all talking constantly, which previous studies have found to spread respiratory droplets just as effectively as coughing (Better Humans, 4/20/20)--a warning that was heavily noted in media's coverage of the risks of chanting protestors (Washington Post, 5/31/20; Politico, 6/8/20), but notably missing from articles on the reopening of workplaces.

"They're pretty high-risk spaces," Boston University School of Public Health epidemiologist Eleanor Murray tells FAIR. "What we would like to see with offices, if people have to be there for the function of the office to work, is to keep the minimum number of people in at any given time." (She also urges consideration of the risk to office cleaning workers, who are seldom included in back-to-work safety debates.)

This is especially key, adds Tulane's Hassig, in office environments where co-workers are breathing the same air. Workers can safely unmask if they're in a private office where they can shut their door, she tells FAIR; however, "if you're in an open office space with little four-foot cubicle walls, everybody needs to be wearing masks all the time."

Yet most states have limited themselves to following CDC guidelines for reopening offices, which mandate wearing masks only when within six feet of a co-worker. But as Bromage (5/6/20) has pointed out, "Social distancing rules are really to protect you with brief exposures or outdoor exposures."

In fact, former Arizona Department of Health Services director Will Humble told Newsweek (6/9/20) that one reason his state became the nation's leader in new infections per capita was that local officials did not go beyond CDC mandates to impose "performance criteria such as required business mitigation measures, contact tracing capacity or mask-wearing." Hassig worries that the CDC's guidance may have been "far less prescriptive than they would like it to be from the scientific perspective," noting that "we've got plenty of evidence that distance is not enough if you're in a shared space with lots of people."

All of this would have been good for US workers returning to their jobs to know, but very little of it has made it into media coverage of reopenings, whether before or after the recent virus spikes. And the rare exceptions often left much to be desired: When CBS News (5/28/20) devoted time to investigating the dangers of reopening offices, it was solely in terms of whether plumbing systems left stagnant during closures could lead to the spread of Legionnaires' disease.

Because it takes at least two to three weeks for case numbers to noticeably rise in response to a change in social distancing rules, Hassig says, states should start slowly, and wait to see if numbers rise before moving on to the next stage of reopening. "If your reopening timetable is preset, that's somewhat of a folly," she says. Ideally, she says, after each change in policy, states should "wait at least three weeks to make a decision before you move on, which would mean that probably you're really looking at a month in each phase. And that is not what Texas did."

It's also not how the Texas media presented reopening plans to the public. The Austin American Statesman (4/27/20, 5/1/20) dutifully listed types of businesses that would resume operations under Gov. Greg Abbott's reopening order, but never cited any independent health officials on the risks each activity would entail. When the Dallas Morning News (4/30/20) ran answers to reader questions about the reopening, the only potential negative consequence it mentioned was whether Texans who refused to return to work could still get unemployment benefits. And the Houston Chronicle (4/30/20) declared, "No more stay-home. Just stay safe"--though the only "safety" measures it mentioned were those still being recommended by Abbott, such as wearing masks in public and limiting the size of gatherings.

The New York Times (5/1/20), meanwhile, chose to both-sides the issue with a story headlined "A Texas-Size Reopening Has Many Wondering: Too Much or Not Enough?"

In doing so, the media largely followed the lead of elected officials, who in many cases let concern over profit-and-loss statements take precedence over whether the data indicated it was safe to resume business as usual. In Ohio, state officials went so far as to allow guidelines to be written by the businesses seeking to reopen themselves (Columbus Dispatch, 6/29/20), something health experts suspect helped lead to a tripling of daily new cases in the state between June 14 and June 25.

The Covid curves in many European and Asian nations that were hit the earliest and took the first and strongest action have remained low, despite reopenings in those nations: Italy, for example, once the world epicenter of the virus, currently has under three new cases per day per million residents, according to Johns Hopkins data--about half the infection rate for the least-hard-hit US state, Vermont.

Those nations, however, took very different approaches to reopening than the US. First off, they waited until case rates were much lower before reopening: When Italy first reopened restaurants on May 18, its daily new-case rate, averaged over the previous week, was 14.4 per million residents; when Florida did so on May 4, its average daily rate was 31.7 per million. "Where you start in terms of your case burden will probably wind up being one of the best predictors of how well your reopening went," says Hassig.

In addition, the measures the European nations took to get cases down that low were much stricter than those ever implemented in the US--something that was largely overlooked in rundowns of nations imposing and lifting lockdowns (New York Times, 6/10/20; CNBC, 6/25/20). "What we were doing in the US compared to what Europe was doing in terms of lockdown are completely different things," says Murray:

I have friends in France, and you had to have a permit that said what time you were allowed to go to the grocery store. So even the places in the US that did a gradual opening were already starting from a much more open place than places in Europe.

US residents can also learn from areas of their own country that have done comparatively well under reopenings. Hassig notes that New Orleans and neighboring Jefferson Parish have provided an unintentional controlled experiment--albeit "a sample of one"--in the efficacy of wearing masks: "The mayor of New Orleans made masking mandatory in indoor spaces, which empowered businesses to put up signs like 'No mask, no shoes, no shirt, no service.'"

The city, which had been an early Covid hotspot, also established a hotline to report violators, kept casinos closed longer, and kept tighter restrictions on such things as church gatherings--with the result, says Hassig, that Orleans Parish currently has less than half the new-case rate of the similarly sized Jefferson Parish. (On Monday, Jefferson Parish announced its own mandatory mask order--New Orleans Advocate, 6/29/20.)

When media outlets posit the decision facing states as balancing the economic needs with public-health needs, it not only ignores that an out-of-control pandemic would be an economic catastrophe (Guardian, 3/26/20), but overlooks another important point: In reopening, governments have a limited amount of risk they can safely spread around without losing control of an outbreak. As a result, reopening decisions don't just impact public health and the economy now--they also could end up undermining your ability to reopen other things down the road.

"It's not 'open' or 'shut'--there's a whole spectrum in between," says Murray. "We need to be thinking about what are the high-priority things that we need to reopen from a functioning point of view, and not an enjoyment point of view."

If the goal is to prevent the kind of explosive surge in Covid cases that many states saw in March and April--and which are now being repeated in new hotspots in June and July--that means picking and choosing carefully, not just which activities are the safest, but which are the most urgent for a functioning society--which, it bears emphasizing, is not the same thing as what's best for businesses' bottom lines.

"We need to be getting dentists' offices open and getting childcare open and getting elective medical treatment open; bars are not as important," advises Murray. "It may be that we have to give up on some of those things to allow the risks that some of these other activities take."

That's a discussion that will require informed public debate on the conditions of reopening, from what should stay closed to whether to require masks. It's a debate that will be much easier if the media spends less time on who is "winning" or "losing" in the struggle to reopen, and more on why people are getting infected--and how they could not be.

"This was an illegal act," said U.S. District Court Judge Paula Xinis.

A federal court judge on Sunday declared the Trump administration's refusal to return a man they sent to an El Salvadoran prison in "error" as "totally lawless" behavior and ordered the Department of Homeland Security to repatriate the man, Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia, within 24 hours.

In a 22-page ruling, U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis doubled down on an order issued Friday, which Department of Justice lawyers representing the administration said was an affront to his executive authority.

"This was an illegal act," Xinis said of DHS Secretary Krisi Noem's attack on Abrego Garcia's rights, including his deportation and imprisonment.

"Defendants seized Abrego Garcia without any lawful authority; held him in three separate domestic detention centers without legal basis; failed to present him to any immigration judge or officer; and forcibly transported him to El Salvador in direct contravention of [immigration law]," the decision states.

Once imprisoned in El Salvador, the order continues, "U.S. officials secured his detention in a facility that, by design, deprives its detainees of adequate food, water, and shelter, fosters routine violence; and places him with his persecutors."

Trump's DOJ appealed Friday's order to 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, based in Virginia, but that court has not yet ruled on the request to stay the order from Xinis, which says Abrego Garcia should be returned to the United States no later than Monday.

"You'd be a fool to think Trump won't go after others he dislikes," warned Sen. Ron Wyden, "including American citizens."

Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon slammed the Trump administration over the weekend in response to fresh reporting that the Department of Homeland Security has intensified its push for access to confidential data held by the Internal Revenue Service—part of a sweeping effort to target immigrant workers who pay into the U.S. tax system yet get little or nothing in return.

Wyden denounced the effort, which had the fingerprints of the Elon Musk-led Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, all over it.

"What Trump and Musk's henchmen are doing by weaponizing taxpayer data is illegal, this abuse of the immigrant community is a moral atrocity, and you'd be a fool to think Trump won't go after others he dislikes, including American citizens," said Wyden, ranking member of the U.S. Senate Finance Committee, on Saturday.

Last week, the White House admitted one of the men it has sent to a prison in El Salvador was detained and deported in schackles in "error." Despite the admitted mistake, and facing a lawsuit for his immediate return, the Trump administration says a federal court has no authority over the president to make such an order.

"Even though the Trump administration claims it's focused on undocumented immigrants, it's obvious that they do not care when they make mistakes and ruin the lives of legal residents and American citizens in the process," Wyden continued. "A repressive scheme on the scale of what they're talking about at the IRS would lead to hundreds if not thousands of those horrific mistakes, and the people who are disappeared as a result may never be returned to their families."

According to the Washington Post reporting on Saturday:

Federal immigration officials are seeking to locate up to 7 million people suspected of being in the United States unlawfully by accessing confidential tax data at the Internal Revenue Service, according to six people familiar with the request, a dramatic escalation in how the Trump administration aims to use the tax system to detain and deport immigrants.

Officials from the Department of Homeland Security had previously sought the IRS’s help in finding 700,000 people who are subject to final removal orders, and they had asked the IRS to use closely guarded taxpayer data systems to provide names and addresses.

As the Post notes, it would be highly unusual, and quite possibly unlawful, for the IRS to share such confidential data. "Normally," the newspaper reports, "personal tax information—even an individual's name and address—is considered confidential and closely guarded within the IRS."

Wyden warned that those who violate the law by disclosing personal tax data face the risk of civil sanction or even prosecution.

"While Trump's sycophants and the DOGE boys may be a lost cause," Wyden said, "IRS personnel need to think long and hard about whether they want to be a part of an effort to round up innocent people and send them to be locked away in foreign torture prisons."

"I'm sure Trump has promised pardons to the people who will commit crimes in the process of abusing legally-protected taxpayer data, but violations of taxpayer privacy laws carry hefty civil penalties too, and Trump cannot pardon anybody out from under those," he said. "I'm going to demand answers from the acting IRS commissioner immediately about this outrageous abuse of the agency.”

"I think that the Democratic Party has to make a fundamental decision," says the independent Senator from Vermont, "and I'm not sure that they will make the right decision."

"I think when we talk about America is a democracy, I think we should rephrase it, call it a 'pseudo-democracy.'"

That's what Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) said Sunday morning in response to questions from CBS News about the state of the nation, with President Donald Trump gutting the federal government from head to toe, challenging constitutional norms, allowing his cabinet of billionaires to run key agencies they philosophically want to destroy, and empowering Elon Musk—the world's richest person—to run roughshod over public education, undermine healthcare programs like Medicare and Medicaid, and attack Social Security.

Taking a weekend away from his ongoing "Fight Oligarchy" tour, which has drawn record crowds in both right-leaning and left-leaning regions of the country over recent weeks, Sanders said the problem is deeply entrenched now in the nation's political system—and both major parties have a lot to answer for.

"One of the other concerns when I talk about oligarchy," Sanders explained to journalist Robert Acosta, "it's not just massive income and wealth inequality. It's not just the power of the billionaire class. These guys, led by Musk—and as a result of this disastrous Citizens United Supreme Court decision—have now allowed billionaires essentially to own our political process. So, I think when we talk about America is a democracy, I think we should rephrase it, call it a 'pseudo-democracy.' And it's not just Musk and the Republicans; it's billionaires in the Democratic Party as well."

Sanders said that while he's been out on the road in various places, what he perceives—from Americans of all stripes—is a shared sense of dread and frustration.

"I think I'm seeing fear, and I'm seeing anger," he said. "Sixty percent of our people are living paycheck-to-paycheck. Media doesn't talk about it. We don't talk about it enough here in Congress."

In a speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate on Friday night, just before the Republican-controlled chamber was able to pass a sweeping spending resolution that will lay waste to vital programs like Medicaid and food assistance to needy families so that billionaires and the ultra-rich can enjoy even more tax giveaways, Sanders said, "What we have is a budget proposal in front of us that makes bad situations much worse and does virtually nothing to protect the needs of working families."

LIVE: I'm on the floor now talking about Trump's totally absurd budget.

They got it exactly backwards. No tax cuts for billionaires by cutting Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid for Americans. https://t.co/ULB2KosOSJ

— Bernie Sanders (@SenSanders) April 4, 2025

What the GOP spending plan does do, he added, "is reward wealthy campaign contributors by providing over $1 trillion in tax breaks for the top one percent."

"I wish my Republican friends the best of luck when they go home—if they dare to hold town hall meetings—and explain to their constituents why they think, at a time of massive income and wealth inequality, it's a great idea to give tax breaks to billionaires and cut Medicaid, education, and other programs that working class families desperately need."

On Saturday, millions of people took to the street in coordinated protests against the Trump administration's attack on government, the economy, and democracy itself.

Voiced at many of the rallies was also a frustration with the failure of the Democrats to stand up to Trump and offer an alternative vision for what the nation can be. In his CBS News interview, Sanders said the key question Democrats need to be asking is the one too many people in Washington, D.C. tend to avoid.

"Why are [the Democrats] held in so low esteem?" That's the question that needs asking, he said.

"Why has the working class in this country largely turned away from them? And what do you have to do to recapture that working class? Do you think working people are voting for Trump because he wants to give massive tax breaks to billionaires and cut Social Security and Medicare? I don't think so. It's because people say, 'I am hurting. Democratic Party has talked a good game for years. They haven't done anything.' So, I think that the Democratic Party has to make a fundamental decision, and I'm not sure that they will make the right decision, which side are they on? [Will] they continue to hustle large campaign contributions from very, very wealthy people, or do they stand with the working class?"

The next leg of Sanders' "Fight Oligarchy' tour will kick off next Saturday, with stops in California, Utah, and Idaho over four days.

"The American people, whether they are Democrats, Republicans or Independents, do not want billionaires to control our government or buy our elections," said Sanders. "That is why I will be visiting Republican-held districts all over the Western United States. When we are organized and fight back, we can defeat oligarchy."