SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"It is clear that the stimulus payment and UI expansions in March dramatically reduced poverty during the initial months of the pandemic," writes Zipperer. (Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

It is often underappreciated how effective public safety net spending and social insurance programs are in reducing poverty. Even in normal years, tens of millions of people are kept out of poverty only because of these programs. As the COVID-19 pandemic hit earlier this year, the importance of public spending in averting poverty became even more evident.

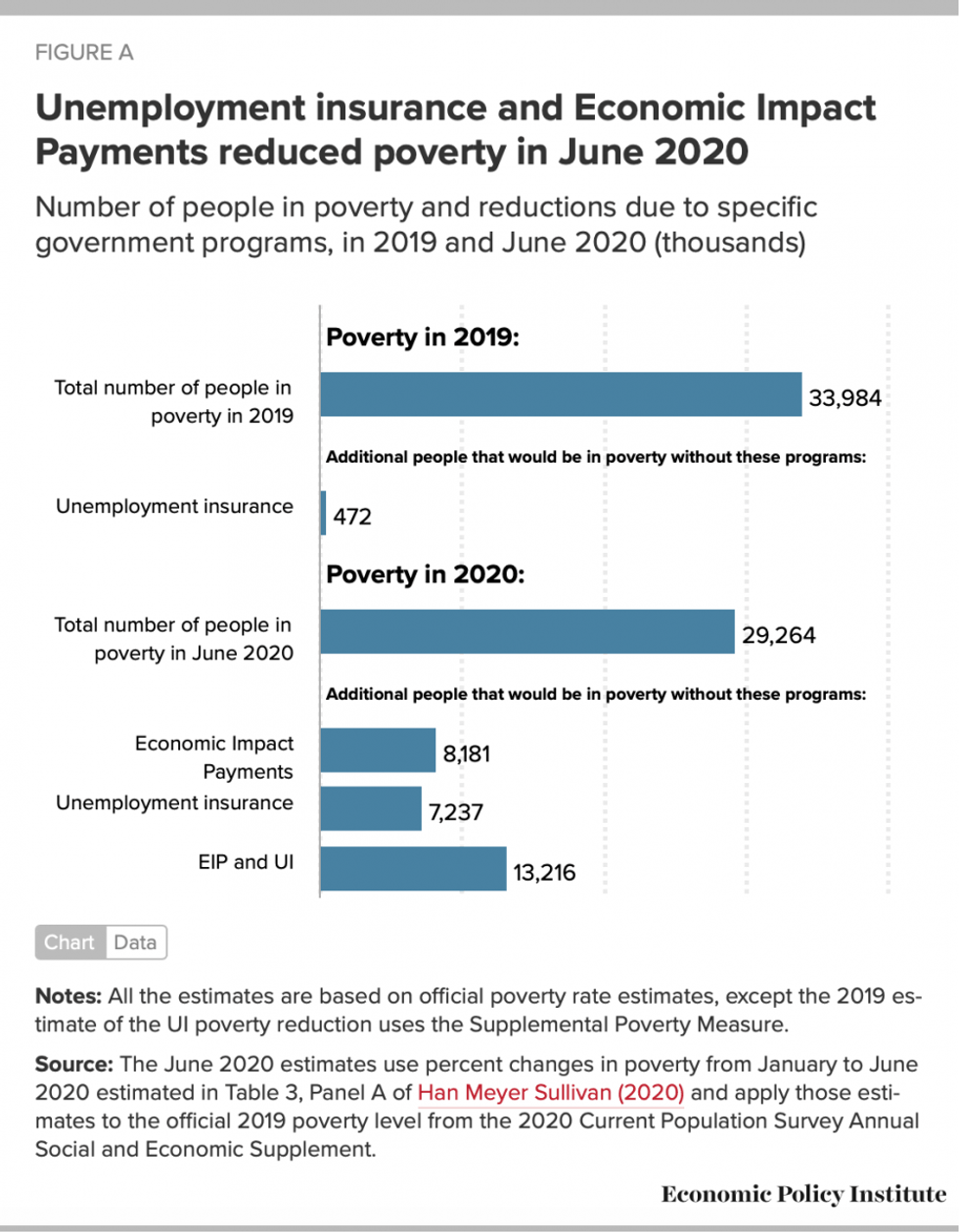

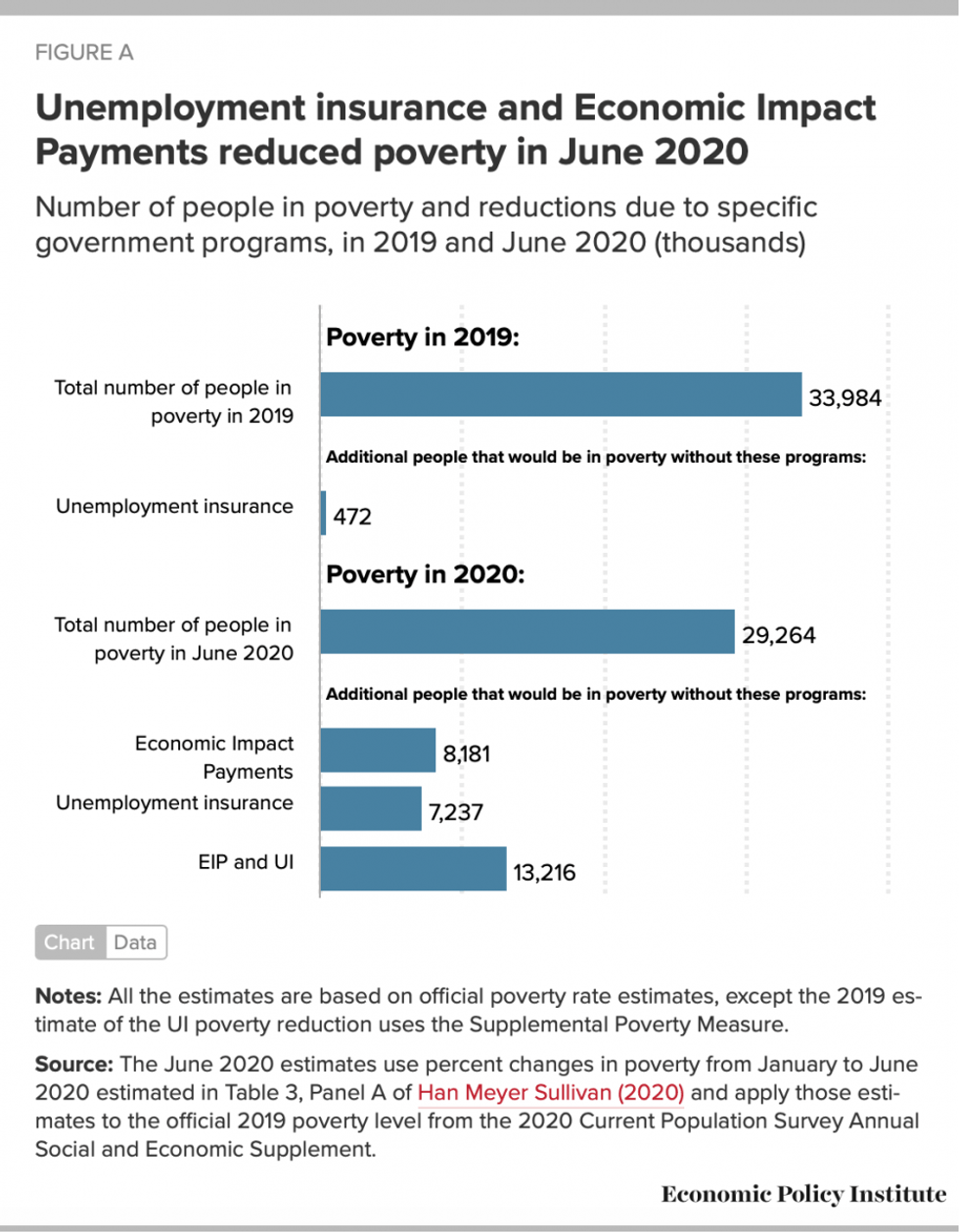

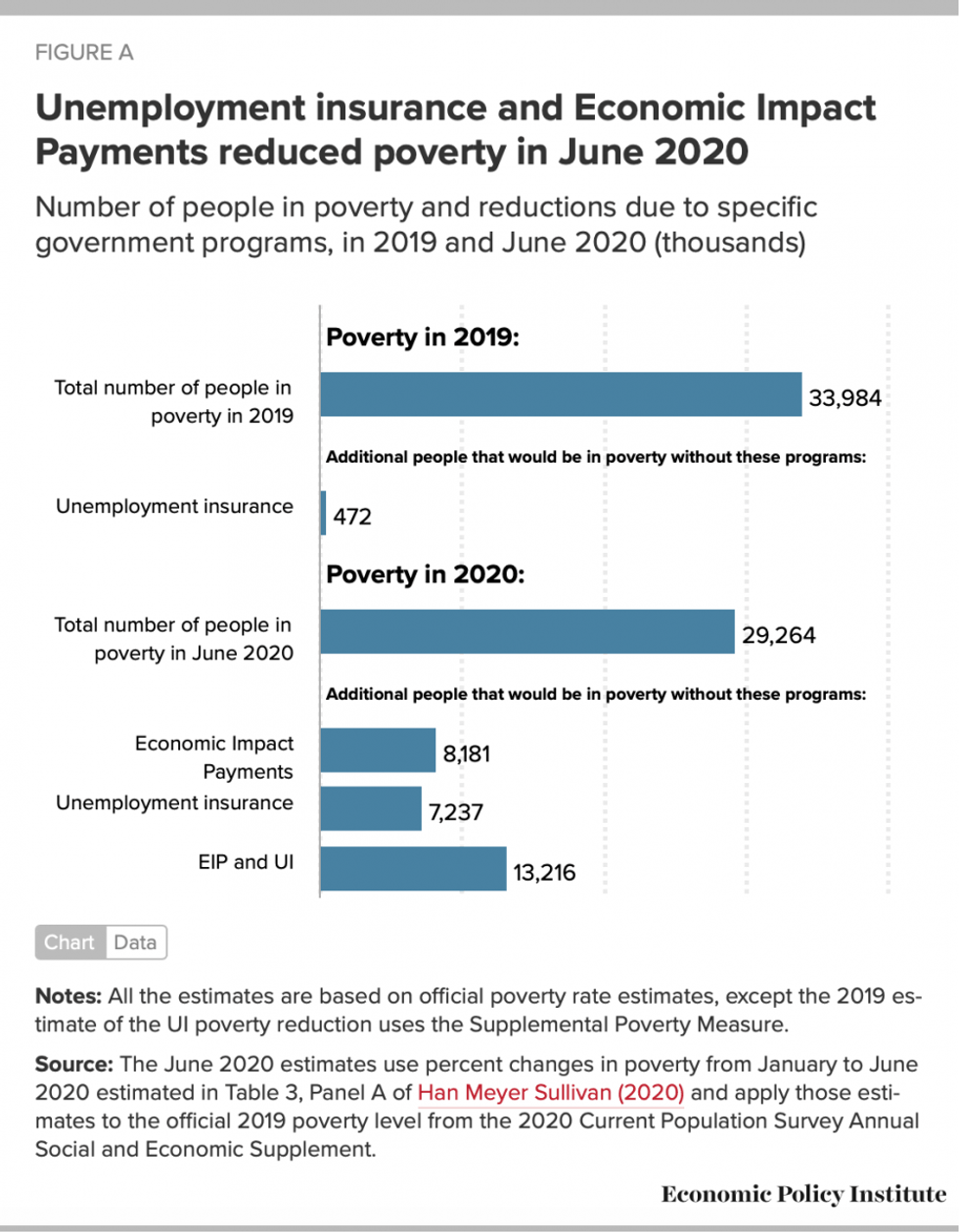

In its annual report on household income and poverty released Tuesday, the Census Bureau estimated that Social Security kept 26.5 million people out of poverty in 2019, and refundable tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit reduced the number of people in poverty by 7.5 million. Unemployment insurance (UI) kept about 472,000 people from being in poverty (see Figure A) in 2019. The relatively small poverty reduction is due to the fact that few people received UI in 2019, both because of relatively low unemployment rates and because many low-wage workers are generally ineligible for UI benefits due to restrictive earnings eligibility requirements.

In March of this year, as job loss began to accelerate, Congress temporarily strengthened the UI system as part of the CARES Act. Notably, it extended eligibility to low-wage, part-time, and self-employed workers, and it added an extra weekly UI benefit of $600. The law also provided a one-time Economic Impact Payment (EIP) of $1,200 per adult and $500 per child.

New research by Jeehoon Han, Bruce Meyer, and James Sullivan estimates that EIP and UI payments between April and June substantially reduced the number of people in poverty, even when millions of workers were suddenly laid off or furloughed. Applying those results to the recently released Census data for 2019 shows that the number of people in poverty fell by 4.7 million between the end of 2019 and June 2020, from 34.0 million to 29.3 million.

The fall in poverty is entirely due to the EIP and UI payments. The EIP alone reduced poverty by 8.2 million workers and the UI programs had a slightly smaller impact, lowering poverty by 7.2 million workers. Had both of those programs not been in place, the effects of the economic shock caused by the pandemic would have increased poverty by 13.2 million people to about 42.5 million people overall living in poverty. These are temporary poverty reductions effective the month of June 2020 because of the one-time nature of the $1,200 check and the July expiration of the supplementary $600 weekly UI benefit.

There is of course some uncertainty about this calculation, as it assumes the 2019 poverty rate is a decent approximation to the unknown poverty rate that we would have experienced in 2020 in the absence of the pandemic. We may overstate the total reduction in poverty due to UI and EIP if an improving labor market throughout 2020 would have continued to reduce poverty below 2019 levels. However, we may be underestimating the poverty reduction, as the Census Bureau has provided evidence that their headline estimates for 2019 undercount the number of people in poverty by as many as 1.9 million due to survey nonresponse issues.

In any case, it is clear that the stimulus payment and UI expansions in March dramatically reduced poverty during the initial months of the pandemic. Unfortunately, the $600 supplementary UI payment expired in July. Senate Republicans blocking its renewal have increased poverty and hardship for millions of families in the middle of a pandemic that has caused widespread job loss and health devastation.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

It is often underappreciated how effective public safety net spending and social insurance programs are in reducing poverty. Even in normal years, tens of millions of people are kept out of poverty only because of these programs. As the COVID-19 pandemic hit earlier this year, the importance of public spending in averting poverty became even more evident.

In its annual report on household income and poverty released Tuesday, the Census Bureau estimated that Social Security kept 26.5 million people out of poverty in 2019, and refundable tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit reduced the number of people in poverty by 7.5 million. Unemployment insurance (UI) kept about 472,000 people from being in poverty (see Figure A) in 2019. The relatively small poverty reduction is due to the fact that few people received UI in 2019, both because of relatively low unemployment rates and because many low-wage workers are generally ineligible for UI benefits due to restrictive earnings eligibility requirements.

In March of this year, as job loss began to accelerate, Congress temporarily strengthened the UI system as part of the CARES Act. Notably, it extended eligibility to low-wage, part-time, and self-employed workers, and it added an extra weekly UI benefit of $600. The law also provided a one-time Economic Impact Payment (EIP) of $1,200 per adult and $500 per child.

New research by Jeehoon Han, Bruce Meyer, and James Sullivan estimates that EIP and UI payments between April and June substantially reduced the number of people in poverty, even when millions of workers were suddenly laid off or furloughed. Applying those results to the recently released Census data for 2019 shows that the number of people in poverty fell by 4.7 million between the end of 2019 and June 2020, from 34.0 million to 29.3 million.

The fall in poverty is entirely due to the EIP and UI payments. The EIP alone reduced poverty by 8.2 million workers and the UI programs had a slightly smaller impact, lowering poverty by 7.2 million workers. Had both of those programs not been in place, the effects of the economic shock caused by the pandemic would have increased poverty by 13.2 million people to about 42.5 million people overall living in poverty. These are temporary poverty reductions effective the month of June 2020 because of the one-time nature of the $1,200 check and the July expiration of the supplementary $600 weekly UI benefit.

There is of course some uncertainty about this calculation, as it assumes the 2019 poverty rate is a decent approximation to the unknown poverty rate that we would have experienced in 2020 in the absence of the pandemic. We may overstate the total reduction in poverty due to UI and EIP if an improving labor market throughout 2020 would have continued to reduce poverty below 2019 levels. However, we may be underestimating the poverty reduction, as the Census Bureau has provided evidence that their headline estimates for 2019 undercount the number of people in poverty by as many as 1.9 million due to survey nonresponse issues.

In any case, it is clear that the stimulus payment and UI expansions in March dramatically reduced poverty during the initial months of the pandemic. Unfortunately, the $600 supplementary UI payment expired in July. Senate Republicans blocking its renewal have increased poverty and hardship for millions of families in the middle of a pandemic that has caused widespread job loss and health devastation.

It is often underappreciated how effective public safety net spending and social insurance programs are in reducing poverty. Even in normal years, tens of millions of people are kept out of poverty only because of these programs. As the COVID-19 pandemic hit earlier this year, the importance of public spending in averting poverty became even more evident.

In its annual report on household income and poverty released Tuesday, the Census Bureau estimated that Social Security kept 26.5 million people out of poverty in 2019, and refundable tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit reduced the number of people in poverty by 7.5 million. Unemployment insurance (UI) kept about 472,000 people from being in poverty (see Figure A) in 2019. The relatively small poverty reduction is due to the fact that few people received UI in 2019, both because of relatively low unemployment rates and because many low-wage workers are generally ineligible for UI benefits due to restrictive earnings eligibility requirements.

In March of this year, as job loss began to accelerate, Congress temporarily strengthened the UI system as part of the CARES Act. Notably, it extended eligibility to low-wage, part-time, and self-employed workers, and it added an extra weekly UI benefit of $600. The law also provided a one-time Economic Impact Payment (EIP) of $1,200 per adult and $500 per child.

New research by Jeehoon Han, Bruce Meyer, and James Sullivan estimates that EIP and UI payments between April and June substantially reduced the number of people in poverty, even when millions of workers were suddenly laid off or furloughed. Applying those results to the recently released Census data for 2019 shows that the number of people in poverty fell by 4.7 million between the end of 2019 and June 2020, from 34.0 million to 29.3 million.

The fall in poverty is entirely due to the EIP and UI payments. The EIP alone reduced poverty by 8.2 million workers and the UI programs had a slightly smaller impact, lowering poverty by 7.2 million workers. Had both of those programs not been in place, the effects of the economic shock caused by the pandemic would have increased poverty by 13.2 million people to about 42.5 million people overall living in poverty. These are temporary poverty reductions effective the month of June 2020 because of the one-time nature of the $1,200 check and the July expiration of the supplementary $600 weekly UI benefit.

There is of course some uncertainty about this calculation, as it assumes the 2019 poverty rate is a decent approximation to the unknown poverty rate that we would have experienced in 2020 in the absence of the pandemic. We may overstate the total reduction in poverty due to UI and EIP if an improving labor market throughout 2020 would have continued to reduce poverty below 2019 levels. However, we may be underestimating the poverty reduction, as the Census Bureau has provided evidence that their headline estimates for 2019 undercount the number of people in poverty by as many as 1.9 million due to survey nonresponse issues.

In any case, it is clear that the stimulus payment and UI expansions in March dramatically reduced poverty during the initial months of the pandemic. Unfortunately, the $600 supplementary UI payment expired in July. Senate Republicans blocking its renewal have increased poverty and hardship for millions of families in the middle of a pandemic that has caused widespread job loss and health devastation.