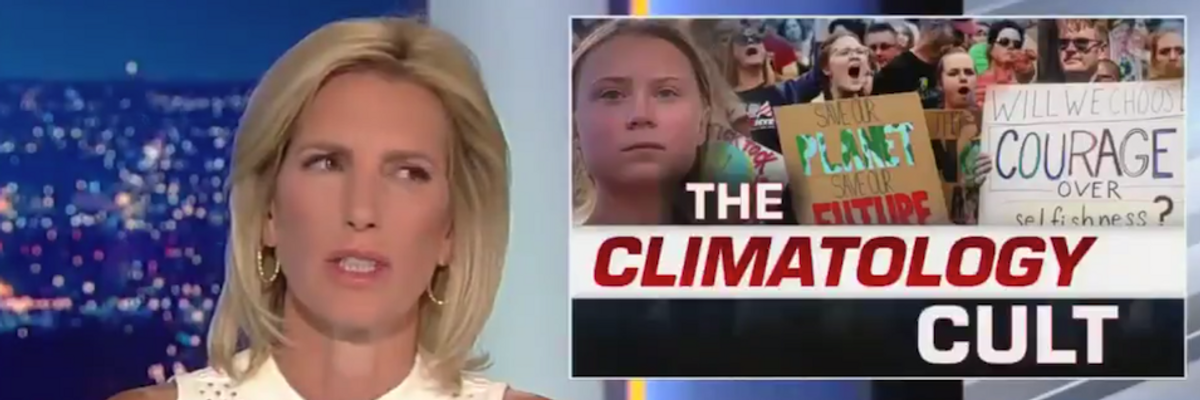

"Fox News, the Republican Party, and the right edge of evangelicalism take the lead, often inspiring each other to new levels of extremism." (Photo: Screenshot)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

"Fox News, the Republican Party, and the right edge of evangelicalism take the lead, often inspiring each other to new levels of extremism." (Photo: Screenshot)

In the midst of a global pandemic, forest fires now take unprecedented area of West Coast real estate, and several hurricanes have battered the East and Gulf Coasts. The continuing and intensifying episodes of climate crisis may provide the sort of shock Naomi Klein has identified as tools to strengthen despots' hold on power and repress or silence dissenters. And since climate crisis is so clearly international, mass migrations will likely become an increasing part of the picture. These will in turn present an opportunity for renewed xenophobia, a kind of twofer for a president desperate to hold power at any cost.

In this context it is important to explore the deeper background of climate science denial. Is this simple ignorance on the part of Trump's base? I fear that emphasis on ignorance is both simplistic and likely to be counterproductive. It strikes me as at least worthy of comment that this issue has ramped up at a time when working class wages remain stagnant and health care initiatives still an indistinct pipe dream.

"The sense that money and technology can overcome nature has emboldened Americans."

Beyond this immediate concern, some theorists view the militant denialism of Trump's base as a form of aggressive nihilism. William Connolly, Krieger-Eisenhower Professor at Johns Hopkins and author of Facing the Planetary: Entangled Humanism and the Politics of Swarming, characterizes nihilism as "the sense that all meaning has been lifted from life if a set of urgently needed beliefs are sorely threatened by events and new interpretations." Prominent amidst the core sustaining beliefs of contemporary US culture is the idea that God infuses the world with divine meaning and providence. Another widely held core belief is that history is set on a progressive trajectory of mastery over nature. Or as ProPublic senior environmental reporter Abrahm Lustgarten puts it: "The sense that money and technology can overcome nature has emboldened Americans."

These views are not consistent with each other, but both share the assumption that one way or another the cosmos is made for us. Its adherents also share an intensity of conviction and a common enemy in liberal government interference with their theological or economic imperialism.

Aggressive nihilism "responds to the shocking evidence" that these core concepts, lodged not merely at the highest level of consciousness but also in more subtle ways in institutional structures and even crude gut level sensibilities, cannot go on as formerly. That response often takes the form of upping the ante of deniability and doubling down on the exact activities that exacerbate the problem. As Connolly puts it, "Fox News, the Republican Party, and the right edge of evangelicalism take the lead, often inspiring each other to new levels of extremism." These levels often include threats of or actual deployment of violence to achieve their goals.

The great danger of aggressive nihilism is that it will forestall remedial action until the crisis becomes so severe that some combination of authoritarian government and an even more harshly inegalitarian economy will prevail. The more subtle danger, however, is that the position is so extreme that those who are opposed will feel that opposition alone is sufficient.

Most American citizens do not share Trump's denialism. I would bet that even many of those citizens who voted for him are not denialists. A recent George Mason/Yale poll found that even a third of Republican voters acknowledge we are living in a climate emergency.

The greater danger is passive nihilism. On the highest levels of consciousness most now believe climate change is real and dangerous. Nonetheless old residues of a crude faith in material progress and a world that exists for us are deeply etched via much of our day to day life over many years. They are lodged at deeper unconscious levels as well having been invested in language and institutional practice so long as to seem merely common sense. These past understandings inhibit people from moving beyond a vague sense of loss toward action on behalf of a effective reforms and a more gentle way of relating to the planet.

Both forms of nihilism must be addressed. Trump's denialism is premised in part on promises to the working class he courted during the campaign. Progressives need to ask those supporters periodically just how many--and how good- jobs he has delivered. The President tells us he loves coal miners. Will that love manifest itself in defense of their pensions or adequate funding of black lung treatment? At the same time many environmentalists must acknowledge how little they accomplished on that front and the ways in which poverty and insecurity make it difficult to worry about the future of the planet. Worse still centrist Democrats must acknowledge the ways their celebration of corporate globalism leaves large segments of the working class feeling they are to blame for their desperate circumstances. Labeling these citizens deplorable only deepens the wound. Thus winning larger sectors of the working class will require more than exposing the manifest deficiencies of Trump.

By the same token, just how effective, how soon, and how passionately embraced these formal policies will be is in part a function of the visceral registers of personal and social life. The good news is that these deeper drives are interdependent, crude, dynamic and thus to some degree susceptible to modification.

George Lakoff , director of the Center for the Neural Mind and Society, discusses the role that framing issues plays, activating the more generous circuitry of the unconscious brain. Framing includes not merely the choice of words, such as public good rather than government spending, protection rather than regulation, or citizens rather than taxpayers. It also includes the narratives in which we wrap public issues. Drawing on French political theorist Gilles Deleuze, Connolly discussed the role that the accumulations of even subtle changes in daily life, including the visitors we bring to our churches, where we buy or grow our food, driving electric vehicles, campaigns to create bike lanes and public transit systems can alter or delete some of the destructive residues of our past.

What Connolly calls arts of the self--including various forms of meditation and manipulation of dream life--also plays a vital role. Arts of the self, micro politics, agonistic respectful debate among scholars and activists working at the more refined levels of discourse regarding the fate of the earth can mutually imbricate each other. A politics of public good is especially important in reshaping visceral attitudes toward consumption and harsher forms of individualism. Together these might enhance appreciation of a pluralizing world and a dynamic, not fully predictable cosmos to which we can contribute but neither can nor should dominate.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

In the midst of a global pandemic, forest fires now take unprecedented area of West Coast real estate, and several hurricanes have battered the East and Gulf Coasts. The continuing and intensifying episodes of climate crisis may provide the sort of shock Naomi Klein has identified as tools to strengthen despots' hold on power and repress or silence dissenters. And since climate crisis is so clearly international, mass migrations will likely become an increasing part of the picture. These will in turn present an opportunity for renewed xenophobia, a kind of twofer for a president desperate to hold power at any cost.

In this context it is important to explore the deeper background of climate science denial. Is this simple ignorance on the part of Trump's base? I fear that emphasis on ignorance is both simplistic and likely to be counterproductive. It strikes me as at least worthy of comment that this issue has ramped up at a time when working class wages remain stagnant and health care initiatives still an indistinct pipe dream.

"The sense that money and technology can overcome nature has emboldened Americans."

Beyond this immediate concern, some theorists view the militant denialism of Trump's base as a form of aggressive nihilism. William Connolly, Krieger-Eisenhower Professor at Johns Hopkins and author of Facing the Planetary: Entangled Humanism and the Politics of Swarming, characterizes nihilism as "the sense that all meaning has been lifted from life if a set of urgently needed beliefs are sorely threatened by events and new interpretations." Prominent amidst the core sustaining beliefs of contemporary US culture is the idea that God infuses the world with divine meaning and providence. Another widely held core belief is that history is set on a progressive trajectory of mastery over nature. Or as ProPublic senior environmental reporter Abrahm Lustgarten puts it: "The sense that money and technology can overcome nature has emboldened Americans."

These views are not consistent with each other, but both share the assumption that one way or another the cosmos is made for us. Its adherents also share an intensity of conviction and a common enemy in liberal government interference with their theological or economic imperialism.

Aggressive nihilism "responds to the shocking evidence" that these core concepts, lodged not merely at the highest level of consciousness but also in more subtle ways in institutional structures and even crude gut level sensibilities, cannot go on as formerly. That response often takes the form of upping the ante of deniability and doubling down on the exact activities that exacerbate the problem. As Connolly puts it, "Fox News, the Republican Party, and the right edge of evangelicalism take the lead, often inspiring each other to new levels of extremism." These levels often include threats of or actual deployment of violence to achieve their goals.

The great danger of aggressive nihilism is that it will forestall remedial action until the crisis becomes so severe that some combination of authoritarian government and an even more harshly inegalitarian economy will prevail. The more subtle danger, however, is that the position is so extreme that those who are opposed will feel that opposition alone is sufficient.

Most American citizens do not share Trump's denialism. I would bet that even many of those citizens who voted for him are not denialists. A recent George Mason/Yale poll found that even a third of Republican voters acknowledge we are living in a climate emergency.

The greater danger is passive nihilism. On the highest levels of consciousness most now believe climate change is real and dangerous. Nonetheless old residues of a crude faith in material progress and a world that exists for us are deeply etched via much of our day to day life over many years. They are lodged at deeper unconscious levels as well having been invested in language and institutional practice so long as to seem merely common sense. These past understandings inhibit people from moving beyond a vague sense of loss toward action on behalf of a effective reforms and a more gentle way of relating to the planet.

Both forms of nihilism must be addressed. Trump's denialism is premised in part on promises to the working class he courted during the campaign. Progressives need to ask those supporters periodically just how many--and how good- jobs he has delivered. The President tells us he loves coal miners. Will that love manifest itself in defense of their pensions or adequate funding of black lung treatment? At the same time many environmentalists must acknowledge how little they accomplished on that front and the ways in which poverty and insecurity make it difficult to worry about the future of the planet. Worse still centrist Democrats must acknowledge the ways their celebration of corporate globalism leaves large segments of the working class feeling they are to blame for their desperate circumstances. Labeling these citizens deplorable only deepens the wound. Thus winning larger sectors of the working class will require more than exposing the manifest deficiencies of Trump.

By the same token, just how effective, how soon, and how passionately embraced these formal policies will be is in part a function of the visceral registers of personal and social life. The good news is that these deeper drives are interdependent, crude, dynamic and thus to some degree susceptible to modification.

George Lakoff , director of the Center for the Neural Mind and Society, discusses the role that framing issues plays, activating the more generous circuitry of the unconscious brain. Framing includes not merely the choice of words, such as public good rather than government spending, protection rather than regulation, or citizens rather than taxpayers. It also includes the narratives in which we wrap public issues. Drawing on French political theorist Gilles Deleuze, Connolly discussed the role that the accumulations of even subtle changes in daily life, including the visitors we bring to our churches, where we buy or grow our food, driving electric vehicles, campaigns to create bike lanes and public transit systems can alter or delete some of the destructive residues of our past.

What Connolly calls arts of the self--including various forms of meditation and manipulation of dream life--also plays a vital role. Arts of the self, micro politics, agonistic respectful debate among scholars and activists working at the more refined levels of discourse regarding the fate of the earth can mutually imbricate each other. A politics of public good is especially important in reshaping visceral attitudes toward consumption and harsher forms of individualism. Together these might enhance appreciation of a pluralizing world and a dynamic, not fully predictable cosmos to which we can contribute but neither can nor should dominate.

In the midst of a global pandemic, forest fires now take unprecedented area of West Coast real estate, and several hurricanes have battered the East and Gulf Coasts. The continuing and intensifying episodes of climate crisis may provide the sort of shock Naomi Klein has identified as tools to strengthen despots' hold on power and repress or silence dissenters. And since climate crisis is so clearly international, mass migrations will likely become an increasing part of the picture. These will in turn present an opportunity for renewed xenophobia, a kind of twofer for a president desperate to hold power at any cost.

In this context it is important to explore the deeper background of climate science denial. Is this simple ignorance on the part of Trump's base? I fear that emphasis on ignorance is both simplistic and likely to be counterproductive. It strikes me as at least worthy of comment that this issue has ramped up at a time when working class wages remain stagnant and health care initiatives still an indistinct pipe dream.

"The sense that money and technology can overcome nature has emboldened Americans."

Beyond this immediate concern, some theorists view the militant denialism of Trump's base as a form of aggressive nihilism. William Connolly, Krieger-Eisenhower Professor at Johns Hopkins and author of Facing the Planetary: Entangled Humanism and the Politics of Swarming, characterizes nihilism as "the sense that all meaning has been lifted from life if a set of urgently needed beliefs are sorely threatened by events and new interpretations." Prominent amidst the core sustaining beliefs of contemporary US culture is the idea that God infuses the world with divine meaning and providence. Another widely held core belief is that history is set on a progressive trajectory of mastery over nature. Or as ProPublic senior environmental reporter Abrahm Lustgarten puts it: "The sense that money and technology can overcome nature has emboldened Americans."

These views are not consistent with each other, but both share the assumption that one way or another the cosmos is made for us. Its adherents also share an intensity of conviction and a common enemy in liberal government interference with their theological or economic imperialism.

Aggressive nihilism "responds to the shocking evidence" that these core concepts, lodged not merely at the highest level of consciousness but also in more subtle ways in institutional structures and even crude gut level sensibilities, cannot go on as formerly. That response often takes the form of upping the ante of deniability and doubling down on the exact activities that exacerbate the problem. As Connolly puts it, "Fox News, the Republican Party, and the right edge of evangelicalism take the lead, often inspiring each other to new levels of extremism." These levels often include threats of or actual deployment of violence to achieve their goals.

The great danger of aggressive nihilism is that it will forestall remedial action until the crisis becomes so severe that some combination of authoritarian government and an even more harshly inegalitarian economy will prevail. The more subtle danger, however, is that the position is so extreme that those who are opposed will feel that opposition alone is sufficient.

Most American citizens do not share Trump's denialism. I would bet that even many of those citizens who voted for him are not denialists. A recent George Mason/Yale poll found that even a third of Republican voters acknowledge we are living in a climate emergency.

The greater danger is passive nihilism. On the highest levels of consciousness most now believe climate change is real and dangerous. Nonetheless old residues of a crude faith in material progress and a world that exists for us are deeply etched via much of our day to day life over many years. They are lodged at deeper unconscious levels as well having been invested in language and institutional practice so long as to seem merely common sense. These past understandings inhibit people from moving beyond a vague sense of loss toward action on behalf of a effective reforms and a more gentle way of relating to the planet.

Both forms of nihilism must be addressed. Trump's denialism is premised in part on promises to the working class he courted during the campaign. Progressives need to ask those supporters periodically just how many--and how good- jobs he has delivered. The President tells us he loves coal miners. Will that love manifest itself in defense of their pensions or adequate funding of black lung treatment? At the same time many environmentalists must acknowledge how little they accomplished on that front and the ways in which poverty and insecurity make it difficult to worry about the future of the planet. Worse still centrist Democrats must acknowledge the ways their celebration of corporate globalism leaves large segments of the working class feeling they are to blame for their desperate circumstances. Labeling these citizens deplorable only deepens the wound. Thus winning larger sectors of the working class will require more than exposing the manifest deficiencies of Trump.

By the same token, just how effective, how soon, and how passionately embraced these formal policies will be is in part a function of the visceral registers of personal and social life. The good news is that these deeper drives are interdependent, crude, dynamic and thus to some degree susceptible to modification.

George Lakoff , director of the Center for the Neural Mind and Society, discusses the role that framing issues plays, activating the more generous circuitry of the unconscious brain. Framing includes not merely the choice of words, such as public good rather than government spending, protection rather than regulation, or citizens rather than taxpayers. It also includes the narratives in which we wrap public issues. Drawing on French political theorist Gilles Deleuze, Connolly discussed the role that the accumulations of even subtle changes in daily life, including the visitors we bring to our churches, where we buy or grow our food, driving electric vehicles, campaigns to create bike lanes and public transit systems can alter or delete some of the destructive residues of our past.

What Connolly calls arts of the self--including various forms of meditation and manipulation of dream life--also plays a vital role. Arts of the self, micro politics, agonistic respectful debate among scholars and activists working at the more refined levels of discourse regarding the fate of the earth can mutually imbricate each other. A politics of public good is especially important in reshaping visceral attitudes toward consumption and harsher forms of individualism. Together these might enhance appreciation of a pluralizing world and a dynamic, not fully predictable cosmos to which we can contribute but neither can nor should dominate.