Close to $40 billion in agriculture-related payments this year mask structural problems in a badly broken market that doesn't pay most farmers enough to continue farming. (Photo: Hero Images/Getty Images)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Close to $40 billion in agriculture-related payments this year mask structural problems in a badly broken market that doesn't pay most farmers enough to continue farming. (Photo: Hero Images/Getty Images)

A farm economy awash in an unprecedented infusion of public dollars directed by the Trump administration could face a reckoning soon. Close to $40 billion in agriculture-related payments this year mask structural problems in a badly broken market that doesn't pay most farmers enough to continue farming. New leadership in the White House and congressional agriculture committees should act to fix a policy framework that has greatly benefited global grain and meat companies at the expense of farmers before these ad hoc Trump payments disappear.

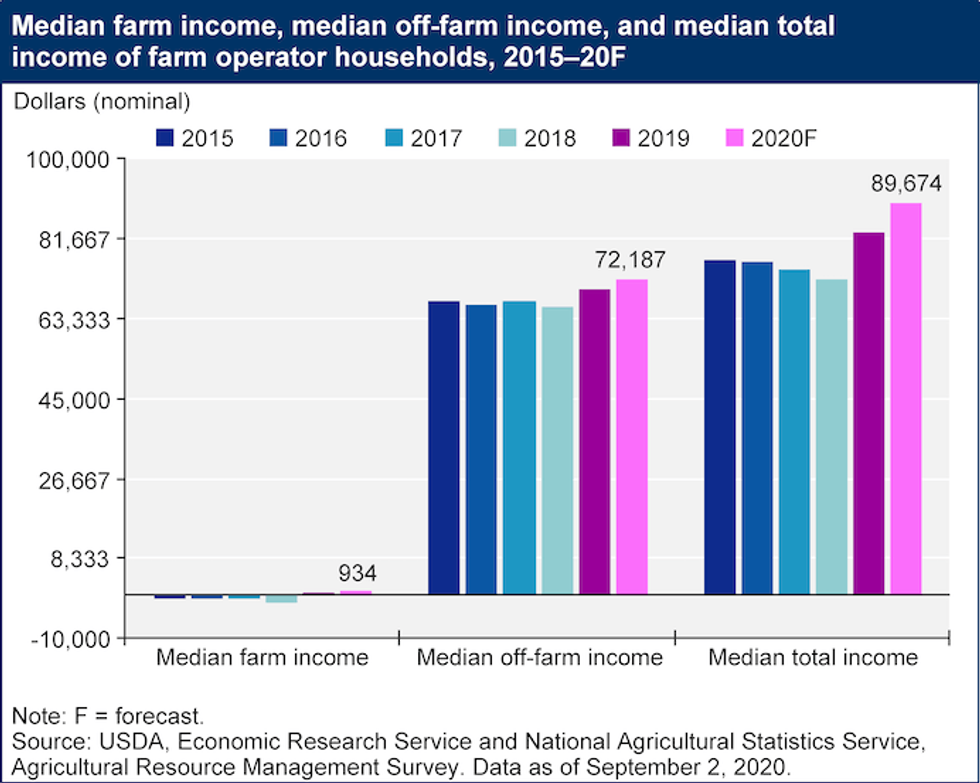

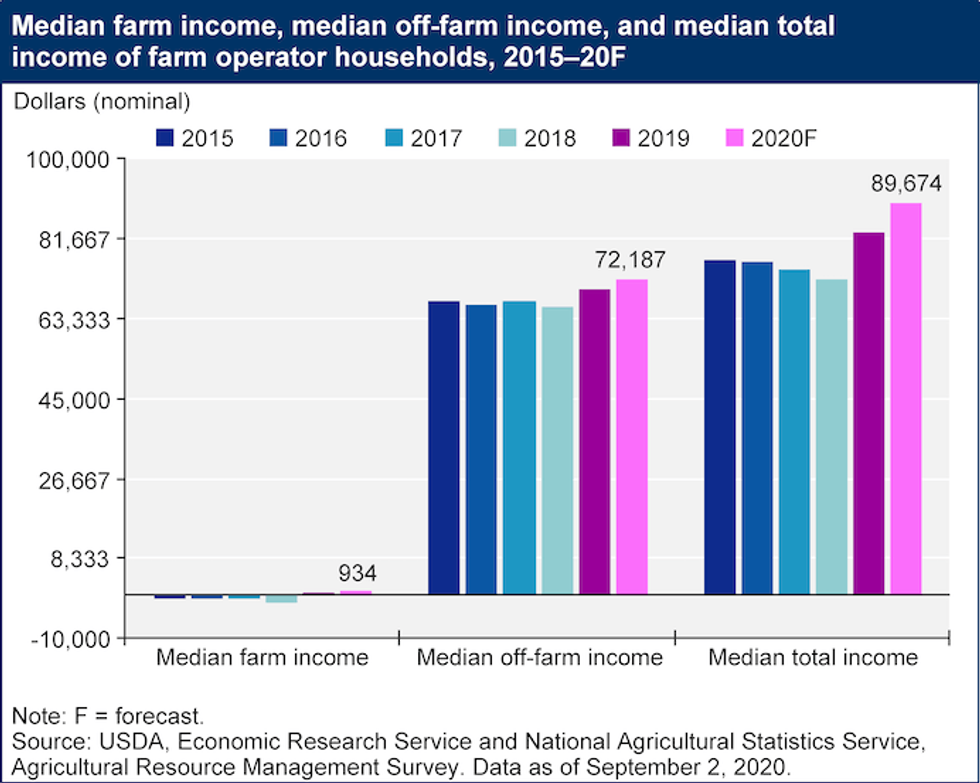

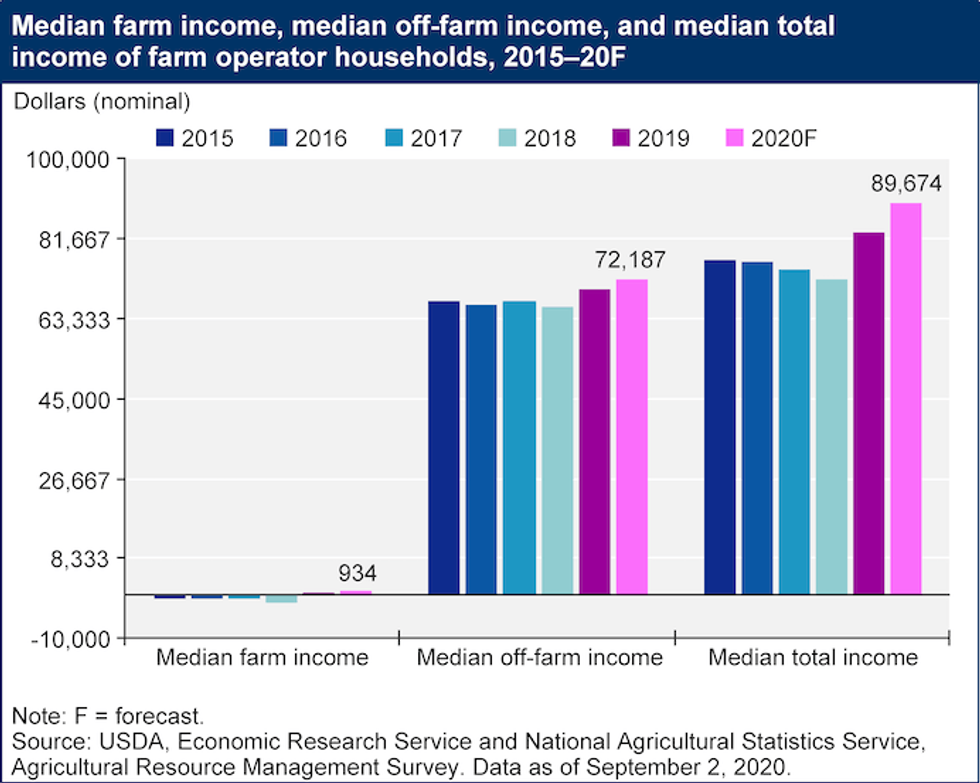

The massive public payments over the last three years help conceal how little farmers have made from the market. The USDA projects median farm income in 2020 will be $934, up from $296 in 2019. Median farm income has been negative from 1996 through 2018. Farm debt is forecast to rise to a record $433 billion in 2020, according to the Congressional Research Service. The farm-to-debt ratio is up 14%, the highest since 2003 after rising steadily over the last eight years. Approximately 8% of loans are in poor condition, double the rate in 2014, according to the Farm Credit Council.

It is off-farm jobs, often coming with a health care plan, that keep most farm families going. While the Trump administration's farm-focused payments (some have said political payoffs) have helped, no one has argued they should be permanent and they are expected to to end or greatly diminish in 2021.

To put the payments in perspective, the estimated $40 billion in 2020 will be the largest government outlay to agricultural producers ever on record in both nominal and inflation-adjusted dollars, according to the CRS. Ad hoc spending (additional to existing Farm Bill programs) to the agriculture economy related to trade fights and the pandemic totaled $22.5 billion in 2018 and $33.9 billion in 2019.

The impact of these payments on farm income has been profound, making up around 36% of farm income in 2020, according to a report from the Fed in October.

Not all farmers are cashing in. Most of the Trump trade payouts went to a very specific sub-set of farmers -- large-scale commodity crop and livestock farmers. A recent analysis by The Counter found that almost 100% of the trade aid payments went to white farmers. Those trade aid payments have been highly criticized for well exceeding losses for certain crops like cotton, disproportionately benefitting farmers in southern states and for going to multinational companies like the meat giant JBS.

COVID-19 aid packages have been similarly concentrated, with the top 10% of recipients getting 62%of the aid. Smaller-scale farmers selling to local institutions or markets, as well as those selling into higher value certified organic or grass-fed markets, have received little or no help from COVID-19 aid packages thus far (though the second round of pandemic aid made improvements).

Perhaps most glaring, food system workers in the fields and meatpacking plants, largely African American and immigrant workers dealing with conditions that drive COVID-19 outbreaks, have received nothing from agriculture-related trade or pandemic aid packages.

The challenge facing the next administration and new congressional agriculture chairs is what to do when farming doesn't pay and massive ad hoc government payouts shrink or disappear. If pandemic and trade aid to the agriculture economy were to stop in 2021, the University of Missouri Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) predicts a potential $16 billion drop in farm income.

We outlined long-standing challenges in the farm economy and policy framework in our Revisiting Crisis by Design series earlier this year. Here are a few immediate steps new leadership could take:

Not responding to these big agriculture market challenges creates real and immediate risks to farm families and rural communities in the coming years, but it also has political risks for decision-makers. If farm income drops as anticipated with an abrupt loss of ad hoc public payments, and there is no push to fix the market, the next president and congressional leaders will be easy targets to take the blame.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

A farm economy awash in an unprecedented infusion of public dollars directed by the Trump administration could face a reckoning soon. Close to $40 billion in agriculture-related payments this year mask structural problems in a badly broken market that doesn't pay most farmers enough to continue farming. New leadership in the White House and congressional agriculture committees should act to fix a policy framework that has greatly benefited global grain and meat companies at the expense of farmers before these ad hoc Trump payments disappear.

The massive public payments over the last three years help conceal how little farmers have made from the market. The USDA projects median farm income in 2020 will be $934, up from $296 in 2019. Median farm income has been negative from 1996 through 2018. Farm debt is forecast to rise to a record $433 billion in 2020, according to the Congressional Research Service. The farm-to-debt ratio is up 14%, the highest since 2003 after rising steadily over the last eight years. Approximately 8% of loans are in poor condition, double the rate in 2014, according to the Farm Credit Council.

It is off-farm jobs, often coming with a health care plan, that keep most farm families going. While the Trump administration's farm-focused payments (some have said political payoffs) have helped, no one has argued they should be permanent and they are expected to to end or greatly diminish in 2021.

To put the payments in perspective, the estimated $40 billion in 2020 will be the largest government outlay to agricultural producers ever on record in both nominal and inflation-adjusted dollars, according to the CRS. Ad hoc spending (additional to existing Farm Bill programs) to the agriculture economy related to trade fights and the pandemic totaled $22.5 billion in 2018 and $33.9 billion in 2019.

The impact of these payments on farm income has been profound, making up around 36% of farm income in 2020, according to a report from the Fed in October.

Not all farmers are cashing in. Most of the Trump trade payouts went to a very specific sub-set of farmers -- large-scale commodity crop and livestock farmers. A recent analysis by The Counter found that almost 100% of the trade aid payments went to white farmers. Those trade aid payments have been highly criticized for well exceeding losses for certain crops like cotton, disproportionately benefitting farmers in southern states and for going to multinational companies like the meat giant JBS.

COVID-19 aid packages have been similarly concentrated, with the top 10% of recipients getting 62%of the aid. Smaller-scale farmers selling to local institutions or markets, as well as those selling into higher value certified organic or grass-fed markets, have received little or no help from COVID-19 aid packages thus far (though the second round of pandemic aid made improvements).

Perhaps most glaring, food system workers in the fields and meatpacking plants, largely African American and immigrant workers dealing with conditions that drive COVID-19 outbreaks, have received nothing from agriculture-related trade or pandemic aid packages.

The challenge facing the next administration and new congressional agriculture chairs is what to do when farming doesn't pay and massive ad hoc government payouts shrink or disappear. If pandemic and trade aid to the agriculture economy were to stop in 2021, the University of Missouri Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) predicts a potential $16 billion drop in farm income.

We outlined long-standing challenges in the farm economy and policy framework in our Revisiting Crisis by Design series earlier this year. Here are a few immediate steps new leadership could take:

Not responding to these big agriculture market challenges creates real and immediate risks to farm families and rural communities in the coming years, but it also has political risks for decision-makers. If farm income drops as anticipated with an abrupt loss of ad hoc public payments, and there is no push to fix the market, the next president and congressional leaders will be easy targets to take the blame.

A farm economy awash in an unprecedented infusion of public dollars directed by the Trump administration could face a reckoning soon. Close to $40 billion in agriculture-related payments this year mask structural problems in a badly broken market that doesn't pay most farmers enough to continue farming. New leadership in the White House and congressional agriculture committees should act to fix a policy framework that has greatly benefited global grain and meat companies at the expense of farmers before these ad hoc Trump payments disappear.

The massive public payments over the last three years help conceal how little farmers have made from the market. The USDA projects median farm income in 2020 will be $934, up from $296 in 2019. Median farm income has been negative from 1996 through 2018. Farm debt is forecast to rise to a record $433 billion in 2020, according to the Congressional Research Service. The farm-to-debt ratio is up 14%, the highest since 2003 after rising steadily over the last eight years. Approximately 8% of loans are in poor condition, double the rate in 2014, according to the Farm Credit Council.

It is off-farm jobs, often coming with a health care plan, that keep most farm families going. While the Trump administration's farm-focused payments (some have said political payoffs) have helped, no one has argued they should be permanent and they are expected to to end or greatly diminish in 2021.

To put the payments in perspective, the estimated $40 billion in 2020 will be the largest government outlay to agricultural producers ever on record in both nominal and inflation-adjusted dollars, according to the CRS. Ad hoc spending (additional to existing Farm Bill programs) to the agriculture economy related to trade fights and the pandemic totaled $22.5 billion in 2018 and $33.9 billion in 2019.

The impact of these payments on farm income has been profound, making up around 36% of farm income in 2020, according to a report from the Fed in October.

Not all farmers are cashing in. Most of the Trump trade payouts went to a very specific sub-set of farmers -- large-scale commodity crop and livestock farmers. A recent analysis by The Counter found that almost 100% of the trade aid payments went to white farmers. Those trade aid payments have been highly criticized for well exceeding losses for certain crops like cotton, disproportionately benefitting farmers in southern states and for going to multinational companies like the meat giant JBS.

COVID-19 aid packages have been similarly concentrated, with the top 10% of recipients getting 62%of the aid. Smaller-scale farmers selling to local institutions or markets, as well as those selling into higher value certified organic or grass-fed markets, have received little or no help from COVID-19 aid packages thus far (though the second round of pandemic aid made improvements).

Perhaps most glaring, food system workers in the fields and meatpacking plants, largely African American and immigrant workers dealing with conditions that drive COVID-19 outbreaks, have received nothing from agriculture-related trade or pandemic aid packages.

The challenge facing the next administration and new congressional agriculture chairs is what to do when farming doesn't pay and massive ad hoc government payouts shrink or disappear. If pandemic and trade aid to the agriculture economy were to stop in 2021, the University of Missouri Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) predicts a potential $16 billion drop in farm income.

We outlined long-standing challenges in the farm economy and policy framework in our Revisiting Crisis by Design series earlier this year. Here are a few immediate steps new leadership could take:

Not responding to these big agriculture market challenges creates real and immediate risks to farm families and rural communities in the coming years, but it also has political risks for decision-makers. If farm income drops as anticipated with an abrupt loss of ad hoc public payments, and there is no push to fix the market, the next president and congressional leaders will be easy targets to take the blame.