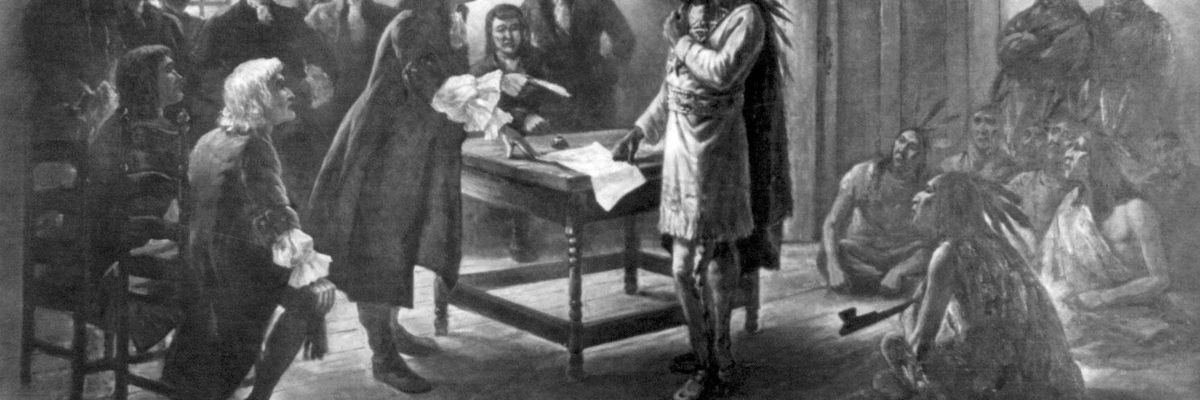

Metacom (King Philip), Wampanoag sachem, meeting settlers, illustration c. 1911. (Photo: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (Digital file no. cph 3c00678))

What Thanksgiving and the Coronavirus Pandemic Share: As Seen from Boston

Perhaps more than any other day, Thanksgiving embodies the underlying embrace of endless growth and voracious consumption: normally the year’s biggest travel day, its reliance on massive amounts of fossil fuel makes the holiday a climate changing event.

This year's Thanksgiving has not turned out as many had hoped. As made clear by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's plea that everyone avoid travel and not spend Thanksgiving with people outside their household, COVID-19 has thrown a wrench in many holiday plans. But we can learn from this misfortune. The lesson is a tragically ironic one: both the holiday's development and epidemiological reasons for its present-day decline are rooted in a settler colonial project centered on the pursuit of wealth and ecological exploitation.

As many Native intellectuals and activists as well as historians have long argued, the depiction of Indians and Pilgrims breaking bread together at the first Thanksgiving in 1621 is inaccurate. It obscures a more complicated, and violent, history. It is one of war, literal and figurative, against the area's indigenous population and the environment.

The arrival of English colonists resulted in myriad, interrelated challenges for the Native population. They included an emerging colonial economy and new trade networks, which profoundly impacted indigenous livelihoods. It also involved the enslavement of many Indians as laborers and their sale in the Caribbean. Moreover, it entailed the transformation of the area's ecological landscape.

Fundamental to this transformation was the large number of colonists, and their voracious hunger for land and, with it, for trees to build and fuel their homes, to construct ships, and for export. Moreover, European plants and animals encroached on Indians' traditional lands; like English plants in relation to the region's indigenous flora, the settlers' cows and pigs consumed their food sources, while crowding out local fauna. As colonial settlements and agricultural establishments grew, so, too, did roads and fences, inhibiting the Native population's mobility and access to the land's abundance.

The many forms of violence and dispossession that the colonists inflicted upon the indigenous population ultimately led to a large-scale uprising in 1675, known as King Philip's War. It was, proportionally speaking, the bloodiest conflict in U.S. history, with many thousands killed. Upwards of 30 percent of English colonists in New England lost their lives, and, according to some estimates, half of the Native population died as a result of the war and associated disease and starvation.

The victory of colonial forces in 1676 ended major resistance to the settler project in what is today Massachusetts. It also facilitated far-reaching ecological destruction that characterizes contemporary Greater Boston and much of the wider world. Perhaps more than any other day, Thanksgiving embodies the underlying embrace of endless growth and voracious consumption: normally the year's biggest travel day, its reliance on massive amounts of fossil fuel makes the holiday a climate changing event.

To speak of Native Greater Boston is not to suggest that indigenous peoples "owned" the land in the way such possession is understood under capitalism. It is, instead, to highlight that they respectfully engaged and shaped the land, made it their home, and laid claim and held collective rights to it, by virtue of custom and membership in political communities.

This lifestyle's high costs are all around us. Here in eastern Massachusetts where Thanksgiving was born, rising sea levels threaten many waterfront communities. Boston, for example, already has more sunny-day flooding than almost any other U.S. municipality. According to various studies, a large share of the housing stock in Boston and nearby cities such as Cambridge and Revere are at risk of permanent inundation or chronic flooding by the end of the century if greenhouse gas emissions continue to climb. Moreover, the health of many of the area's forests is under great threat, largely due to air pollution and climate change. And toxic algae now ravage freshwater ponds throughout Cape Cod because of warming temperatures and pollution.

These changes dovetail with one of the key sources of growing vulnerability to pandemics such as COVID-19: accelerating habitat loss. Cutting down forests and expanding towns, cities, and industrial activities create pathways for animal microbes to adapt to humans. As non-human animal species cram into smaller fragments of habitat, the likelihood that they will encounter human settlements increases. This allows the microbes in their bodies to cross over into ours, transforming benign microbes into deadly human pathogens.

What was and still is "Native Greater Boston" offers a different path.

To speak of Native Greater Boston is not to suggest that indigenous peoples "owned" the land in the way such possession is understood under capitalism. It is, instead, to highlight that they respectfully engaged and shaped the land, made it their home, and laid claim and held collective rights to it, by virtue of custom and membership in political communities. It also underscores the region's enduring Native presence.

Native Greater Boston is what colonialism sought to refute and, in many ways, continues to negate. In the name of "improvement," English colonists denied indigenous land stewardship, using Indians' seasonal mobility and light environmental footprint as "proof" of non-possession. This repudiation was central to Native dispossession and the active denial of their traditional land rights; it was also fundamental to the carving up of the land and the turning of it into state and private property.

Massasoit, a Wampanoag sachem and the father of Metacom (a.k.a. King Philip) reflected on this process during the 1630s: "What is this you call property? It cannot be the Earth for the land is our Mother nourishing all her children, beasts, birds, fish, and all men. The woods, the streams, everything on it belong to everybody and is for the use of all. How can one man say it belongs to him?"

These words and the underlying ethic resonate four centuries later. They illuminate the marked inequality, ecological degradation, and increasing epidemiological threats that plague the modern world that Greater Boston helped to birth. Addressing them with humility, with a spirit that sees all life forms as interdependent and a willingness to share the Earth's bounty and to live sustainably, is central to the undoing and transformation of the unjust social and ecological relations at the heart of both what remains colonial Greater Boston and the larger world.

Achieving anything less will ensure only greater disruptions and tragedy than we are now experiencing.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

This year's Thanksgiving has not turned out as many had hoped. As made clear by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's plea that everyone avoid travel and not spend Thanksgiving with people outside their household, COVID-19 has thrown a wrench in many holiday plans. But we can learn from this misfortune. The lesson is a tragically ironic one: both the holiday's development and epidemiological reasons for its present-day decline are rooted in a settler colonial project centered on the pursuit of wealth and ecological exploitation.

As many Native intellectuals and activists as well as historians have long argued, the depiction of Indians and Pilgrims breaking bread together at the first Thanksgiving in 1621 is inaccurate. It obscures a more complicated, and violent, history. It is one of war, literal and figurative, against the area's indigenous population and the environment.

The arrival of English colonists resulted in myriad, interrelated challenges for the Native population. They included an emerging colonial economy and new trade networks, which profoundly impacted indigenous livelihoods. It also involved the enslavement of many Indians as laborers and their sale in the Caribbean. Moreover, it entailed the transformation of the area's ecological landscape.

Fundamental to this transformation was the large number of colonists, and their voracious hunger for land and, with it, for trees to build and fuel their homes, to construct ships, and for export. Moreover, European plants and animals encroached on Indians' traditional lands; like English plants in relation to the region's indigenous flora, the settlers' cows and pigs consumed their food sources, while crowding out local fauna. As colonial settlements and agricultural establishments grew, so, too, did roads and fences, inhibiting the Native population's mobility and access to the land's abundance.

The many forms of violence and dispossession that the colonists inflicted upon the indigenous population ultimately led to a large-scale uprising in 1675, known as King Philip's War. It was, proportionally speaking, the bloodiest conflict in U.S. history, with many thousands killed. Upwards of 30 percent of English colonists in New England lost their lives, and, according to some estimates, half of the Native population died as a result of the war and associated disease and starvation.

The victory of colonial forces in 1676 ended major resistance to the settler project in what is today Massachusetts. It also facilitated far-reaching ecological destruction that characterizes contemporary Greater Boston and much of the wider world. Perhaps more than any other day, Thanksgiving embodies the underlying embrace of endless growth and voracious consumption: normally the year's biggest travel day, its reliance on massive amounts of fossil fuel makes the holiday a climate changing event.

To speak of Native Greater Boston is not to suggest that indigenous peoples "owned" the land in the way such possession is understood under capitalism. It is, instead, to highlight that they respectfully engaged and shaped the land, made it their home, and laid claim and held collective rights to it, by virtue of custom and membership in political communities.

This lifestyle's high costs are all around us. Here in eastern Massachusetts where Thanksgiving was born, rising sea levels threaten many waterfront communities. Boston, for example, already has more sunny-day flooding than almost any other U.S. municipality. According to various studies, a large share of the housing stock in Boston and nearby cities such as Cambridge and Revere are at risk of permanent inundation or chronic flooding by the end of the century if greenhouse gas emissions continue to climb. Moreover, the health of many of the area's forests is under great threat, largely due to air pollution and climate change. And toxic algae now ravage freshwater ponds throughout Cape Cod because of warming temperatures and pollution.

These changes dovetail with one of the key sources of growing vulnerability to pandemics such as COVID-19: accelerating habitat loss. Cutting down forests and expanding towns, cities, and industrial activities create pathways for animal microbes to adapt to humans. As non-human animal species cram into smaller fragments of habitat, the likelihood that they will encounter human settlements increases. This allows the microbes in their bodies to cross over into ours, transforming benign microbes into deadly human pathogens.

What was and still is "Native Greater Boston" offers a different path.

To speak of Native Greater Boston is not to suggest that indigenous peoples "owned" the land in the way such possession is understood under capitalism. It is, instead, to highlight that they respectfully engaged and shaped the land, made it their home, and laid claim and held collective rights to it, by virtue of custom and membership in political communities. It also underscores the region's enduring Native presence.

Native Greater Boston is what colonialism sought to refute and, in many ways, continues to negate. In the name of "improvement," English colonists denied indigenous land stewardship, using Indians' seasonal mobility and light environmental footprint as "proof" of non-possession. This repudiation was central to Native dispossession and the active denial of their traditional land rights; it was also fundamental to the carving up of the land and the turning of it into state and private property.

Massasoit, a Wampanoag sachem and the father of Metacom (a.k.a. King Philip) reflected on this process during the 1630s: "What is this you call property? It cannot be the Earth for the land is our Mother nourishing all her children, beasts, birds, fish, and all men. The woods, the streams, everything on it belong to everybody and is for the use of all. How can one man say it belongs to him?"

These words and the underlying ethic resonate four centuries later. They illuminate the marked inequality, ecological degradation, and increasing epidemiological threats that plague the modern world that Greater Boston helped to birth. Addressing them with humility, with a spirit that sees all life forms as interdependent and a willingness to share the Earth's bounty and to live sustainably, is central to the undoing and transformation of the unjust social and ecological relations at the heart of both what remains colonial Greater Boston and the larger world.

Achieving anything less will ensure only greater disruptions and tragedy than we are now experiencing.

This year's Thanksgiving has not turned out as many had hoped. As made clear by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's plea that everyone avoid travel and not spend Thanksgiving with people outside their household, COVID-19 has thrown a wrench in many holiday plans. But we can learn from this misfortune. The lesson is a tragically ironic one: both the holiday's development and epidemiological reasons for its present-day decline are rooted in a settler colonial project centered on the pursuit of wealth and ecological exploitation.

As many Native intellectuals and activists as well as historians have long argued, the depiction of Indians and Pilgrims breaking bread together at the first Thanksgiving in 1621 is inaccurate. It obscures a more complicated, and violent, history. It is one of war, literal and figurative, against the area's indigenous population and the environment.

The arrival of English colonists resulted in myriad, interrelated challenges for the Native population. They included an emerging colonial economy and new trade networks, which profoundly impacted indigenous livelihoods. It also involved the enslavement of many Indians as laborers and their sale in the Caribbean. Moreover, it entailed the transformation of the area's ecological landscape.

Fundamental to this transformation was the large number of colonists, and their voracious hunger for land and, with it, for trees to build and fuel their homes, to construct ships, and for export. Moreover, European plants and animals encroached on Indians' traditional lands; like English plants in relation to the region's indigenous flora, the settlers' cows and pigs consumed their food sources, while crowding out local fauna. As colonial settlements and agricultural establishments grew, so, too, did roads and fences, inhibiting the Native population's mobility and access to the land's abundance.

The many forms of violence and dispossession that the colonists inflicted upon the indigenous population ultimately led to a large-scale uprising in 1675, known as King Philip's War. It was, proportionally speaking, the bloodiest conflict in U.S. history, with many thousands killed. Upwards of 30 percent of English colonists in New England lost their lives, and, according to some estimates, half of the Native population died as a result of the war and associated disease and starvation.

The victory of colonial forces in 1676 ended major resistance to the settler project in what is today Massachusetts. It also facilitated far-reaching ecological destruction that characterizes contemporary Greater Boston and much of the wider world. Perhaps more than any other day, Thanksgiving embodies the underlying embrace of endless growth and voracious consumption: normally the year's biggest travel day, its reliance on massive amounts of fossil fuel makes the holiday a climate changing event.

To speak of Native Greater Boston is not to suggest that indigenous peoples "owned" the land in the way such possession is understood under capitalism. It is, instead, to highlight that they respectfully engaged and shaped the land, made it their home, and laid claim and held collective rights to it, by virtue of custom and membership in political communities.

This lifestyle's high costs are all around us. Here in eastern Massachusetts where Thanksgiving was born, rising sea levels threaten many waterfront communities. Boston, for example, already has more sunny-day flooding than almost any other U.S. municipality. According to various studies, a large share of the housing stock in Boston and nearby cities such as Cambridge and Revere are at risk of permanent inundation or chronic flooding by the end of the century if greenhouse gas emissions continue to climb. Moreover, the health of many of the area's forests is under great threat, largely due to air pollution and climate change. And toxic algae now ravage freshwater ponds throughout Cape Cod because of warming temperatures and pollution.

These changes dovetail with one of the key sources of growing vulnerability to pandemics such as COVID-19: accelerating habitat loss. Cutting down forests and expanding towns, cities, and industrial activities create pathways for animal microbes to adapt to humans. As non-human animal species cram into smaller fragments of habitat, the likelihood that they will encounter human settlements increases. This allows the microbes in their bodies to cross over into ours, transforming benign microbes into deadly human pathogens.

What was and still is "Native Greater Boston" offers a different path.

To speak of Native Greater Boston is not to suggest that indigenous peoples "owned" the land in the way such possession is understood under capitalism. It is, instead, to highlight that they respectfully engaged and shaped the land, made it their home, and laid claim and held collective rights to it, by virtue of custom and membership in political communities. It also underscores the region's enduring Native presence.

Native Greater Boston is what colonialism sought to refute and, in many ways, continues to negate. In the name of "improvement," English colonists denied indigenous land stewardship, using Indians' seasonal mobility and light environmental footprint as "proof" of non-possession. This repudiation was central to Native dispossession and the active denial of their traditional land rights; it was also fundamental to the carving up of the land and the turning of it into state and private property.

Massasoit, a Wampanoag sachem and the father of Metacom (a.k.a. King Philip) reflected on this process during the 1630s: "What is this you call property? It cannot be the Earth for the land is our Mother nourishing all her children, beasts, birds, fish, and all men. The woods, the streams, everything on it belong to everybody and is for the use of all. How can one man say it belongs to him?"

These words and the underlying ethic resonate four centuries later. They illuminate the marked inequality, ecological degradation, and increasing epidemiological threats that plague the modern world that Greater Boston helped to birth. Addressing them with humility, with a spirit that sees all life forms as interdependent and a willingness to share the Earth's bounty and to live sustainably, is central to the undoing and transformation of the unjust social and ecological relations at the heart of both what remains colonial Greater Boston and the larger world.

Achieving anything less will ensure only greater disruptions and tragedy than we are now experiencing.