SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Sen. Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) passes Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.W.) as Manchin speaks on the phone outside the room where Democrats met for their weekly policy luncheon at the U.S. Capitol on November 13, 2014 in Washington, D.C. (Photo: Win McNamee/Getty Images)

Joe Manchin said Monday that he will not, under any circumstances, "vote to get rid of the filibuster." Kyrsten Sinema echoed her West Virginia colleague. Mitch McConnell took the Democratic senators at their word.

But that doesn't necessarily mean that you should.

For the Democratic Party as an institution, the stakes of enacting major reforms over the next two years are nearly existential. And its leadership appears to understand this, even if its marginal senators do not.

The newly elected Senate is divided 50-50 between members of the Republican and Democratic caucuses. Vice-President Kamala Harris's tie-breaking vote gives Chuck Schumer an effective majority. But the even split within the upper chamber provided McConnell with an opportunity to throw the new Senate into dysfunction before it had even begun: In order to seat the body's new committee members, McConnell and Schumer had to reach consensus on a "power-sharing agreement."

As part of this agreement, the minority leader demanded that Democrats include a written commitment to preserve the legislative filibuster, the Senate rule that has established a de facto 60-vote threshold for the passage of all major bills. Schumer refused. The Senate ground to a halt.

As a constitutional matter, Senate majorities boast sovereignty over their chamber. Even if Democrats acquiesced to McConnell's demand, it would have remained within their power to change the rules on a party-line basis later in the term. But surrender would have made pulling such an about-face a tad more politically difficult. More importantly, it would have made it harder for Schumer to wield the threat of filibuster abolition as a cudgel in negotiations with Republicans over Biden's legislative agenda. Manchin, for his part, seemed to understand this, as Reuters reported last week:

Moderate Democrats like Senator Joe Manchin favor keeping the legislative filibuster. But even Manchin supports Schumer sticking to his guns and not making any promises to McConnell, keeping the threat of going "nuclear" on legislation in reserve if Republicans do not work cooperatively.

"Chuck has the right to do what he's doing," Manchin told reporters this week. "He has the right to use that to leverage in whatever he wants to do."

And yet, on Monday night, Manchin appeared to take that leverage out of Schumer's hands by voicing unconditional, unequivocal support for preserving the filibuster:

"If I haven't said it very plain, maybe Sen. McConnell hasn't understood, I want to basically say it for you. That I will not vote in this Congress, that's two years, right? I will not vote" to change the filibuster, Manchin (D-W.Va.) said...Asked if there is any scenario that would change his mind, he replied: "None whatsoever that I will vote to get rid of the filibuster."

McConnell decided to declare that this press report was an unofficial addendum to the Senate's power-sharing agreement--and that he was, therefore, the winner of the standoff. (In reality, McConnell was likely looking for an exit ramp, as maintaining the status quo meant denying his new members their committee assignments.)

For Democrats who would prefer for their party to not squander its first chance to govern in a decade (and/or last chance to avert America's descent into semi-permanent minority rule), hope now lies in the incoherence of Manchin's position: If the West Virginia senator is as unconditionally opposed to altering the filibuster as his recent remarks suggest, then it is not clear why he supported Schumer holding the line against McConnell's demand in the first place, much less why he would suggest that doing so provides the majority leader with "leverage."

This may seem like a rather thin reed on which to hang high hopes. And it is. But if the outlook for filibuster abolition looks dim, Blue America's civil war over the issue is far from over. For the Democratic Party as an institution, the stakes of enacting major reforms over the next two years are nearly existential. And its leadership appears to understand this, even if its marginal senators do not (and/or care not for their party's fate).

The basic problem facing the Democratic Party is simple: Barring an extraordinary change to America's political landscape, it will lose control of Congress in 2022 and have a difficult time regaining control for a decade thereafter.

To be sure, the assumption that existing political trends will continue indefinitely has been leading pundits astray since the advent of our loathsome profession. And in certain respects, the future of our politics looks more uncertain than at any time in recent memory. For example, the fact that a critical mass of Republican voters now belong to the personality cult of a narcissistic con man--who has no real investment in the conservative movement's well-being--makes the prospect of the GOP fracturing more thinkable than it's been in about a century.

This said, the trends bedeviling Democrats have been in motion for decades and are rooted in America's most durable political divides. To summarize the party's predicament: As a result of 19th-century efforts to gerrymander the Senate, the middle of our country is chock full of heavily white, low-population, rural states. This has always been a problem for the party of urban America--by boasting stronger support in rural areas, Republicans have long punched above their weight in the race for control of state governments and the Senate. But for most of the 20th century, this advantage was mitigated by the Democrats' (1) vestigial support in the post-Confederate South and (2) ability to render local issues more salient than national ones in Senate elections. Over the past two decades, however, urban-rural polarization in U.S. politics has reached unprecedented heights, while the collapse of local journalism and rise of the internet has made all politics national. Voters have never been less likely to split their tickets, and white rural areas have never been more likely to vote for Republicans. This is plausibly because the (irreversible, internet-induced) nationalization of politics has increased rural white voters' awareness of the myriad ways that urban, college-educated Democrats differ from them culturally. If this is the case, then the Democratic Party may have only a limited ability to reverse urban-rural polarization in the near-term future.

It took a series of minor miracles for the party to eke out its current 50-vote majority. By coincidence, Democrats happened to have their most vulnerable incumbent senators on the ballot two years ago, when the party rode anti-Trump fervor to one of the largest midterm landslides in American history. And yet: Winning the House popular vote by 8.6 percent was not sufficient to prevent the party from losing Senate seats. And although Jon Tester and Joe Manchin won reelection in their deep-red states, both underperformed the national environment: In a year when the nation as a whole favored Democrats by more than eight points, both Democratic incumbents won their races by a bit over three points. Which is to say, had those senators been on the ballot last year instead, when the national environment favored Democrats by "only" 4.4 percent, they likely would have lost. Or, to put the matter more pointedly: Unless the Democratic nominee orchestrates an extraordinary landslide in 2024, Manchin and Tester will likely return to the private sector by mid-decade.

Meanwhile, attempts to mint new "Joe Manchins"--i.e., idiosyncratic Democrats whose strong local ties overwhelm the taint of the party's brand in white rural America--have invariably failed in the post-Trump era. Two years after Tester won reelection in Montana, the state's Democratic governor didn't come within ten points of winning his Senate race in 2020.

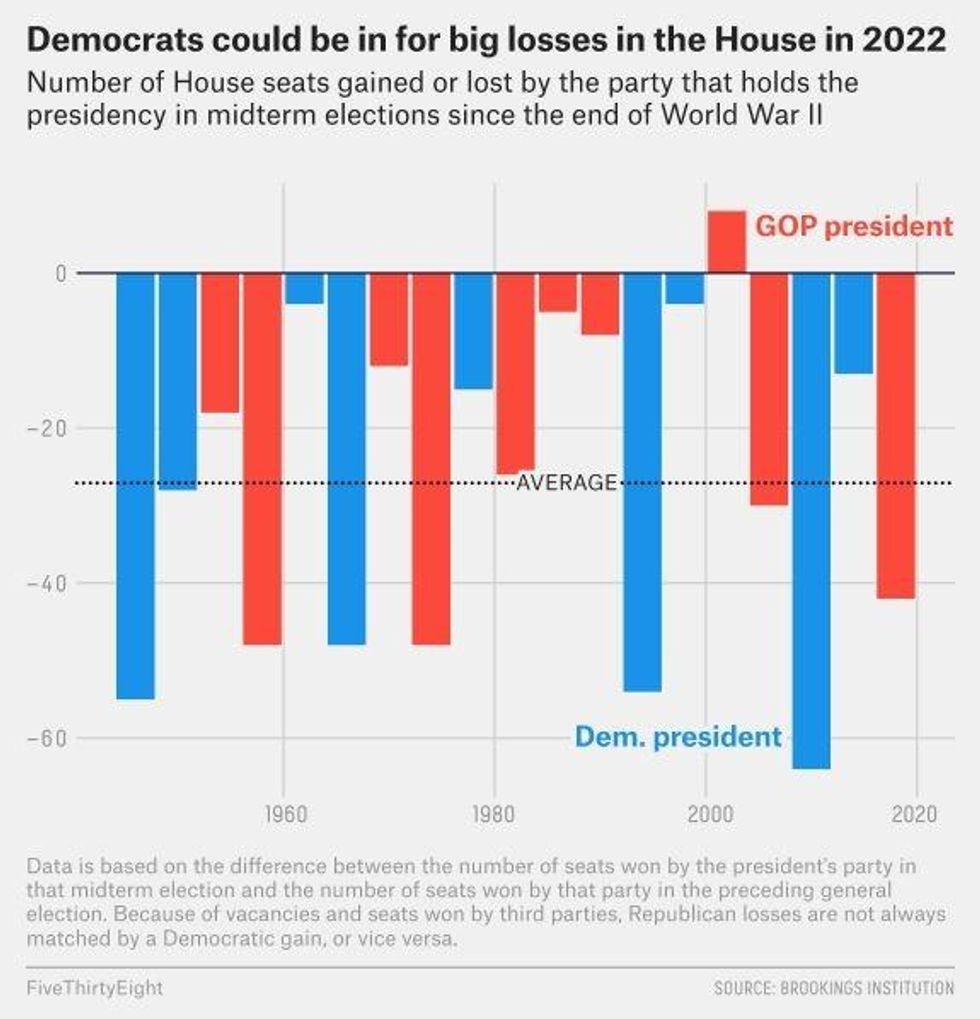

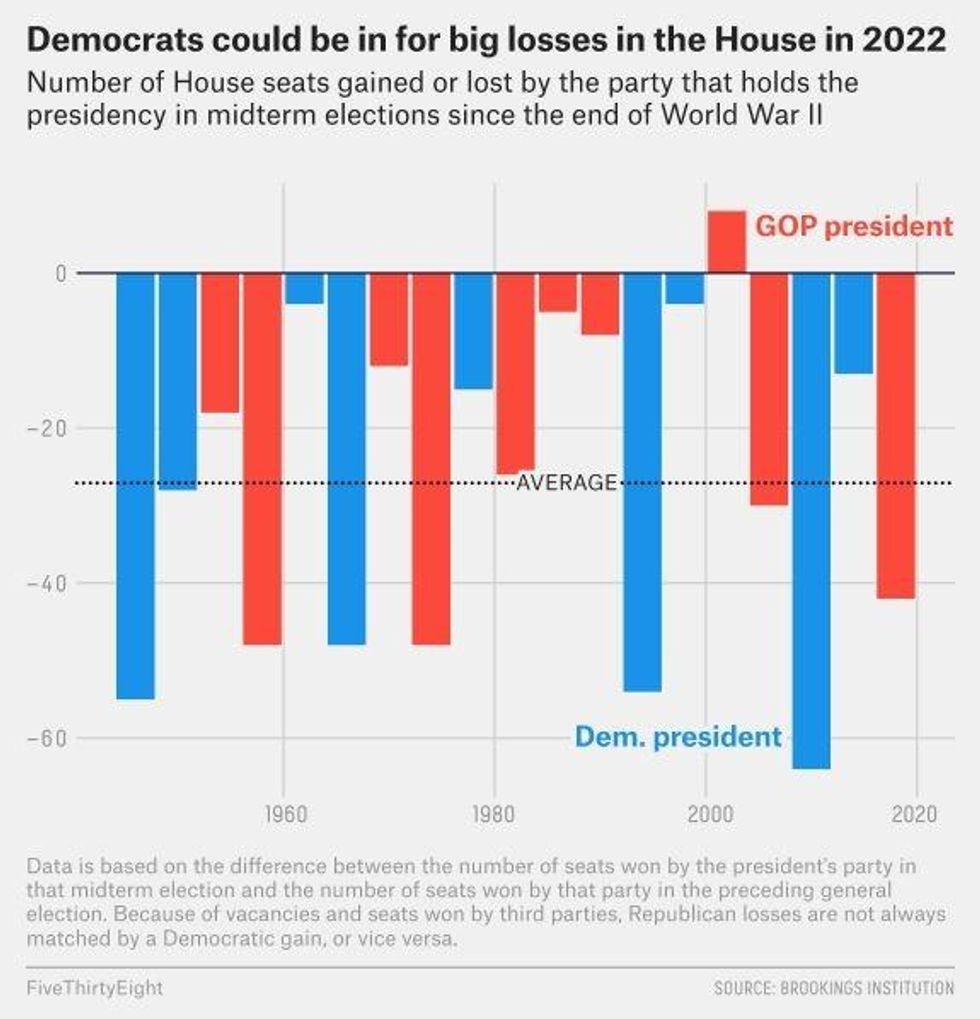

The party's outlook in the House of Representatives isn't much better. The abundance of predominantly white rural states doesn't just give Republicans an advantage in the Senate; it also gives them an advantage in fights over redistricting. Since there are more solidly red states than there are solidly blue ones, Republicans have more opportunities to gerrymander House maps than Democrats do. What's more, even in the absence of gerrymandering, the convention of drawing geographically compact districts naturally underrepresents Democrats, since their support is more geographically concentrated in urban centers than the GOP's support is in low-density areas.

This is one reason why Democrats lost House seats in the 2020 election. Now, with the new Census set to empower the GOP to produce an even more biased House map before 2022, Republicans have an excellent chance of retaking the House two years from now.

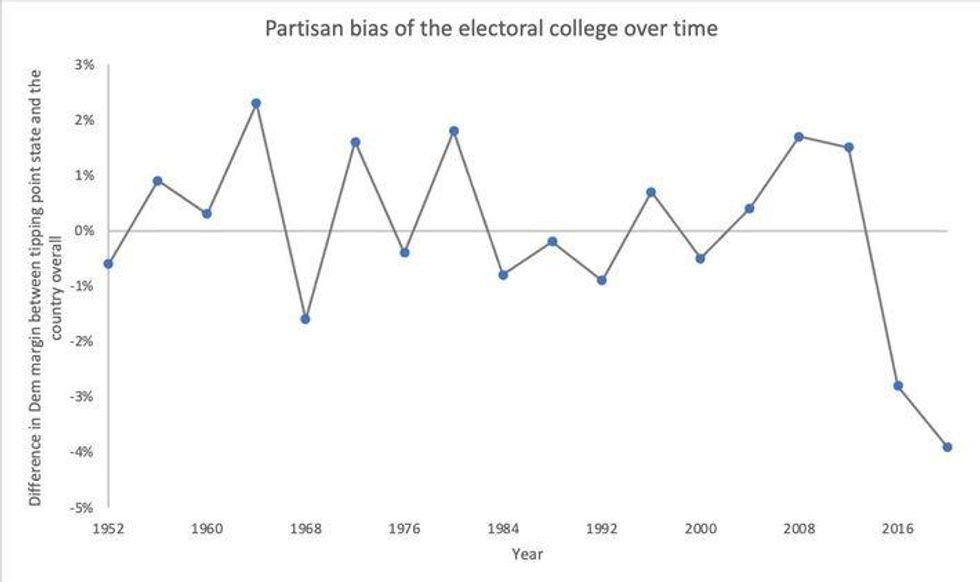

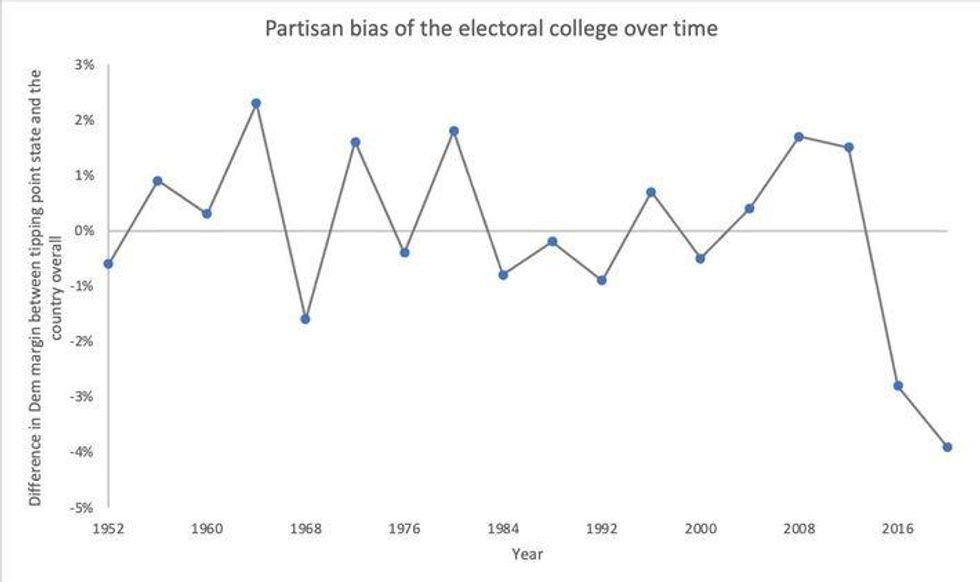

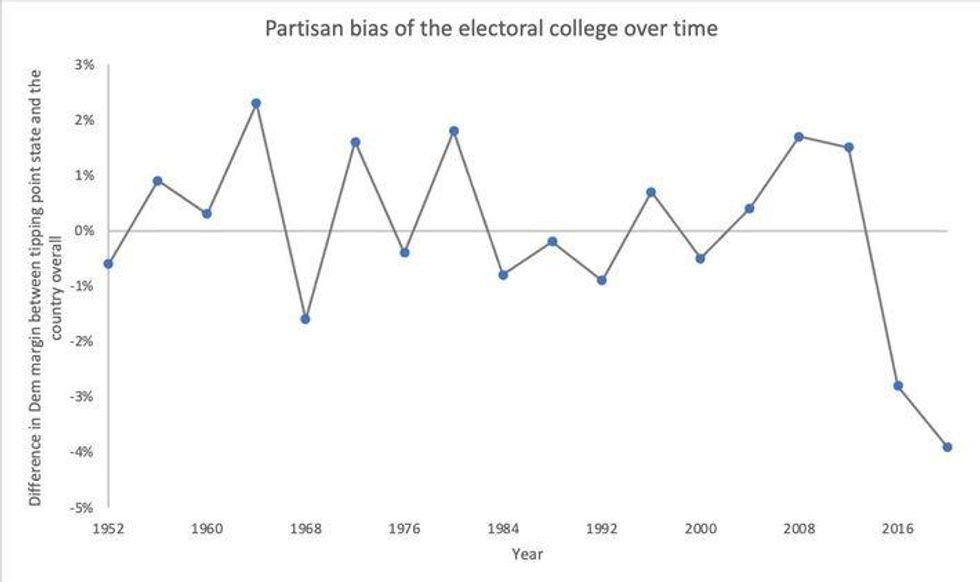

Making matters even more dire: (1) The Electoral College now has a four-point pro-GOP bias, meaning that if Biden wins the two-way popular vote by "only" 3.9 percent in 2024, he will have a less than 50 percent chance of winning reelection, and (2) the Republican Party has grown more openly contemptuous of democracy since Donald Trump's defeat. If the GOP does gain full control of the federal government in 2024, there is a significant risk it will further entrench its structural advantages through anti-democratic measures, so as to insulate right-wing minority rule against the threat of demographic change.

To defy political gravity, and fortify U.S. democracy against the threat of authoritarian reaction, Democrats need to either rebalance the electoral playing field through the passage of structural reforms, or attain a degree of popularity that no in-power party has achieved in modern memory. If the filibuster remains in place, doing the former will be impossible and the latter highly unlikely.

The Constitution limits the Democrats' capacity to correct the biases of America's governing institutions. But the party could significantly reduce the overrepresentation of white rural America in the Senate by granting statehood to the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and any other U.S. territory that wants it. The party could also prohibit partisan redistricting, ban felon disenfranchisement, erode practical barriers to the political participation of working-class people and immigrants, make it easier for workers to form unions (which are both good for democracy and Democrats), grant citizenship to 11 million undocumented immigrants, and pack the Supreme Court if it interferes with the implementation of these reforms.

To defy political gravity, and fortify U.S. democracy against the threat of authoritarian reaction, Democrats need to either rebalance the electoral playing field through the passage of structural reforms, or attain a degree of popularity that no in-power party has achieved in modern memory.

But none of those measures are going to attract ten Republican votes in the Senate. And none of them are achievable through the budget-reconciliation process.

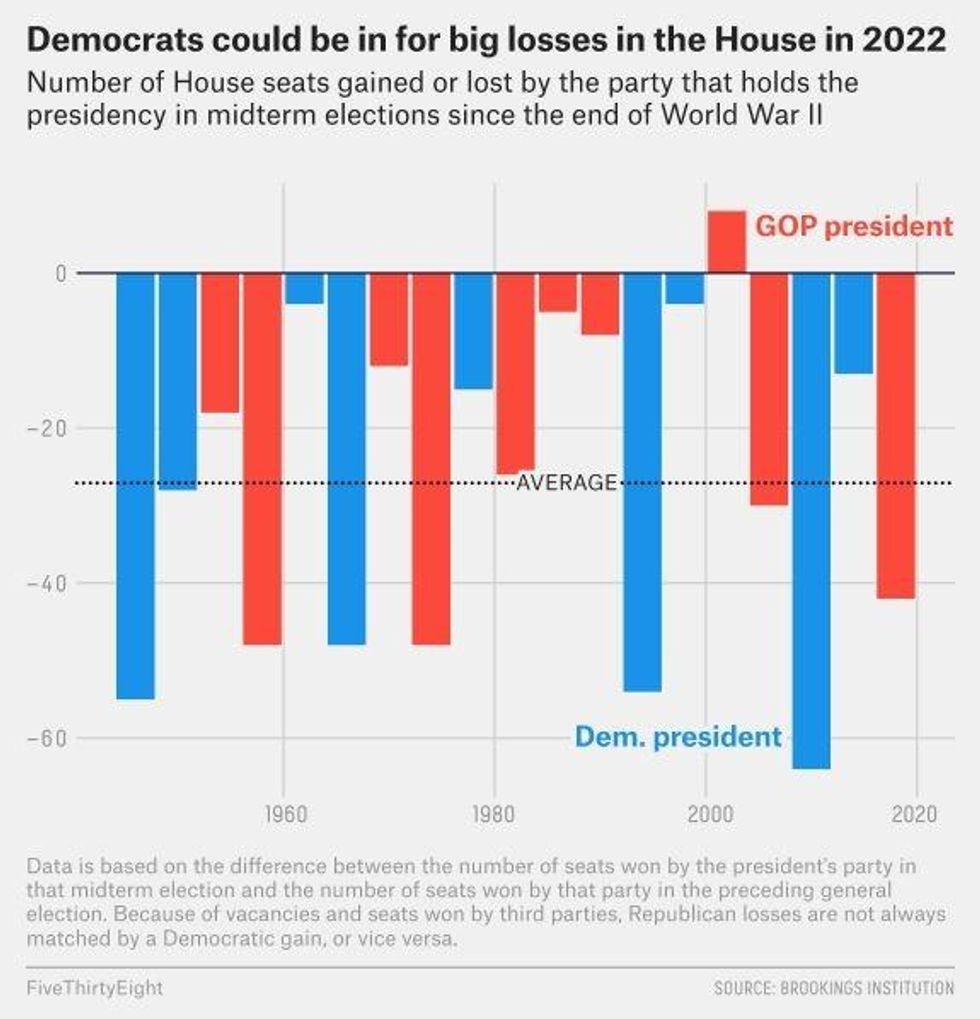

If Democrats do not pass structural reforms, their odds of retaining both chambers of Congress in 2022 aren't good. The president's party almost always loses seats in midterms. And due to the GOP's structural advantages, even if Democrats replicated the Republican Party's post-9/11 performance in the 2002 elections--the only time this century that an in-power party gained ground--they might well still lose the House.

All this said, Democrats could have some extraordinary winds at their back. Biden has a decent shot of presiding over a post-pandemic economic boom. To the extent that Democrats can juice that recovery with further growth and wage-boosting measures--while maintaining the enthusiasm of their core interest groups--they may pull off the unprecedented in 2022.

But it's hard to see how the party can do that while leaving the filibuster fully intact. Democrats will be incapable of honoring their (now decade-old) IOUs to civil-rights organizations, labor unions, and immigrant communities if they allow the Senate's 60-vote threshold to remain in place. In a kinder political universe, Democratic control of the federal government would not be an aberration akin to a Buffalo Bills playoff win. In such a world, Democrats could pacify their core constituencies by pointing to the slimness of their current Senate majority and promising to deliver on their promises after they win more seats in 2022. In the world we actually live in, however, the NAACP and AFL-CIO have every reason to believe that this is the last Democratic trifecta they're going to see in some time.

Meanwhile, America's rising generations of millennials and zoomers--who are both more left wing than any of their predecessors and more distrustful of the major parties--are unlikely to grade the unified Democratic government on a curve. Keeping these cohorts invested in electoral politics, and rooted in "blue America," is vital to the Democratic Party's medium-term prospects. If the Biden presidency features two years of tepid reform followed by a midterm wipeout, younger, left-leaning voters may grow disaffected with electoral politics. (In this way, the GOP's structural advantages may be self-reinforcing: How many times can you watch your party win the popular vote but lose the election, and/or win the presidency but fail to govern, before you stop bothering to cast a ballot?)

All this makes it difficult for the Democratic leadership to accept the constraints that the filibuster, and the ideological orientation of its marginal senators, place on the prospects for reform.

Following Manchin and Sinema's remarks Monday night, Schumer assured reporters, "We are not letting McConnell dictate how the Senate operates." The majority leader then went on Maddow and vowed to pass major climate-, racial-justice-, and democracy-reform legislation. His office, meanwhile, declared victory in the standoff with McConnell and promised to get "big, bold things done for the American people."

In the immediate term, the Democrats' internal conflict over the filibuster will move to the backburner. Joe Biden's Covid-relief package and green-infrastructure "recovery" plan consist primarily of tax-and-spending measures that the party can advance through the budget-reconciliation process. And Schumer has signaled that he intends to bend the rules of that process as far as the Senate parliamentarian will let him, arguing that both a ban on new vehicles with internal-combustion engines and a $15 minimum wage are actually, primarily means of reducing government spending, when you really think about it.

But once reconciliation is done, attention will turn to the large stack of Democratic-coalition priorities that are currently subject to a 60-vote requirement. It will not be easy for Schumer to tell the NAACP that his caucus values a "Senate tradition" (that is anti-constitutional, historically associated with Jim Crow rule, and less than two decades old in its present form) more than it values a new Voting Rights Act. Nor will it be easy for the majority leader to tell organized labor that it will just have to wait until next time to see a $15 minimum wage (assuming that doesn't get through reconciliation) or collective-bargaining reform. And it might be hard for Schumer to accept that he probably won't ever wield majority power again after 2022 because his caucus would rather maintain the GOP's structural advantage in the upper chamber than abolish the filibuster and add new states.

It might be hard for Schumer to accept that he probably won't ever wield majority power again after 2022 because his caucus would rather maintain the GOP's structural advantage in the upper chamber than abolish the filibuster and add new states.

For these reasons, Schumer, Senate Democrat Whip Dick Durbin, and Delaware senator (and Biden confidant) Chris Coons have all telegraphed an intention to eliminate the filibuster if McConnell obstructs their coalition's priorities. The apparent hope is that--while Manchin, Sinema, and a few others support the filibuster in the abstract--in the heat of a legislative battle over voting rights or a $15 minimum wage, they may consent to weakening the filibuster while lamenting what Mitch McConnell is making them do.

Sinema and Manchin have repeatedly insisted that they will not "eliminate" or "get rid of" the filibuster. But there are plenty of ways to erode the Senate's 60-vote requirement that stop short of filibuster abolition. You could create new exemptions, modeled on budget reconciliation, that allow for the passage of certain categories of legislation by simple majority vote. Or you could restore the requirement for those mounting a filibuster to speak continuously from the Senate floor. Or you could throw every Democratic priority into a reconciliation bill and then let Kamala Harris overrule the parliamentarian when she objects.

But Manchin & Co.'s cooperation with this scheme is far from assured. The Democratic Party has a vital interest in passing sweeping reforms that gratify its base and mitigate its structural disadvantages. But Joe Manchin doesn't necessarily have an interest in the institutional health of the Democratic Party.

Our Republic's founders famously disdained political parties. And partisanship is a pejorative in contemporary American discourse. But our democracy's present affliction lies in the weakness of its parties, not in their strength. Were the GOP a stronger institution, the Trump presidency would never have happened. Were the Democratic leadership capable of formulating and enforcing a party line, the filibuster would not be long for this Earth.

While the Constitution failed to stymie the advent of political parties, it has kept them weaker than their overseas analogs. The Democratic Party is more of a loose association of elected officeholders than a coherent mass-member organization. As such, it has limited capacity to dictate terms to any of its incumbent senators, let alone to those whose job security would be enhanced by becoming Republicans. If Joe Manchin votes to abolish the filibuster, he will increase his personal power--but also likely expose himself to a series of "can't win" votes on legislation that divides his idiosyncratic voting base of Democrats and right-leaning independents. A strong Democratic Party might be capable of brokering a deal between its moderate senators, interest groups, and activists (e.g., "We'll abolish the filibuster if you'll focus your advocacy on a discrete set of mutually agreeable issues and pork for our home states"). The existing Democratic Party probably can't.

Thus the Democrats' existential interest in eroding the filibuster remains on a collision course with its moderate senators' aversion to power. Anyone with a fondness for democracy must hope that, against all odds, the forces of partisanship will prevail.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Joe Manchin said Monday that he will not, under any circumstances, "vote to get rid of the filibuster." Kyrsten Sinema echoed her West Virginia colleague. Mitch McConnell took the Democratic senators at their word.

But that doesn't necessarily mean that you should.

For the Democratic Party as an institution, the stakes of enacting major reforms over the next two years are nearly existential. And its leadership appears to understand this, even if its marginal senators do not.

The newly elected Senate is divided 50-50 between members of the Republican and Democratic caucuses. Vice-President Kamala Harris's tie-breaking vote gives Chuck Schumer an effective majority. But the even split within the upper chamber provided McConnell with an opportunity to throw the new Senate into dysfunction before it had even begun: In order to seat the body's new committee members, McConnell and Schumer had to reach consensus on a "power-sharing agreement."

As part of this agreement, the minority leader demanded that Democrats include a written commitment to preserve the legislative filibuster, the Senate rule that has established a de facto 60-vote threshold for the passage of all major bills. Schumer refused. The Senate ground to a halt.

As a constitutional matter, Senate majorities boast sovereignty over their chamber. Even if Democrats acquiesced to McConnell's demand, it would have remained within their power to change the rules on a party-line basis later in the term. But surrender would have made pulling such an about-face a tad more politically difficult. More importantly, it would have made it harder for Schumer to wield the threat of filibuster abolition as a cudgel in negotiations with Republicans over Biden's legislative agenda. Manchin, for his part, seemed to understand this, as Reuters reported last week:

Moderate Democrats like Senator Joe Manchin favor keeping the legislative filibuster. But even Manchin supports Schumer sticking to his guns and not making any promises to McConnell, keeping the threat of going "nuclear" on legislation in reserve if Republicans do not work cooperatively.

"Chuck has the right to do what he's doing," Manchin told reporters this week. "He has the right to use that to leverage in whatever he wants to do."

And yet, on Monday night, Manchin appeared to take that leverage out of Schumer's hands by voicing unconditional, unequivocal support for preserving the filibuster:

"If I haven't said it very plain, maybe Sen. McConnell hasn't understood, I want to basically say it for you. That I will not vote in this Congress, that's two years, right? I will not vote" to change the filibuster, Manchin (D-W.Va.) said...Asked if there is any scenario that would change his mind, he replied: "None whatsoever that I will vote to get rid of the filibuster."

McConnell decided to declare that this press report was an unofficial addendum to the Senate's power-sharing agreement--and that he was, therefore, the winner of the standoff. (In reality, McConnell was likely looking for an exit ramp, as maintaining the status quo meant denying his new members their committee assignments.)

For Democrats who would prefer for their party to not squander its first chance to govern in a decade (and/or last chance to avert America's descent into semi-permanent minority rule), hope now lies in the incoherence of Manchin's position: If the West Virginia senator is as unconditionally opposed to altering the filibuster as his recent remarks suggest, then it is not clear why he supported Schumer holding the line against McConnell's demand in the first place, much less why he would suggest that doing so provides the majority leader with "leverage."

This may seem like a rather thin reed on which to hang high hopes. And it is. But if the outlook for filibuster abolition looks dim, Blue America's civil war over the issue is far from over. For the Democratic Party as an institution, the stakes of enacting major reforms over the next two years are nearly existential. And its leadership appears to understand this, even if its marginal senators do not (and/or care not for their party's fate).

The basic problem facing the Democratic Party is simple: Barring an extraordinary change to America's political landscape, it will lose control of Congress in 2022 and have a difficult time regaining control for a decade thereafter.

To be sure, the assumption that existing political trends will continue indefinitely has been leading pundits astray since the advent of our loathsome profession. And in certain respects, the future of our politics looks more uncertain than at any time in recent memory. For example, the fact that a critical mass of Republican voters now belong to the personality cult of a narcissistic con man--who has no real investment in the conservative movement's well-being--makes the prospect of the GOP fracturing more thinkable than it's been in about a century.

This said, the trends bedeviling Democrats have been in motion for decades and are rooted in America's most durable political divides. To summarize the party's predicament: As a result of 19th-century efforts to gerrymander the Senate, the middle of our country is chock full of heavily white, low-population, rural states. This has always been a problem for the party of urban America--by boasting stronger support in rural areas, Republicans have long punched above their weight in the race for control of state governments and the Senate. But for most of the 20th century, this advantage was mitigated by the Democrats' (1) vestigial support in the post-Confederate South and (2) ability to render local issues more salient than national ones in Senate elections. Over the past two decades, however, urban-rural polarization in U.S. politics has reached unprecedented heights, while the collapse of local journalism and rise of the internet has made all politics national. Voters have never been less likely to split their tickets, and white rural areas have never been more likely to vote for Republicans. This is plausibly because the (irreversible, internet-induced) nationalization of politics has increased rural white voters' awareness of the myriad ways that urban, college-educated Democrats differ from them culturally. If this is the case, then the Democratic Party may have only a limited ability to reverse urban-rural polarization in the near-term future.

It took a series of minor miracles for the party to eke out its current 50-vote majority. By coincidence, Democrats happened to have their most vulnerable incumbent senators on the ballot two years ago, when the party rode anti-Trump fervor to one of the largest midterm landslides in American history. And yet: Winning the House popular vote by 8.6 percent was not sufficient to prevent the party from losing Senate seats. And although Jon Tester and Joe Manchin won reelection in their deep-red states, both underperformed the national environment: In a year when the nation as a whole favored Democrats by more than eight points, both Democratic incumbents won their races by a bit over three points. Which is to say, had those senators been on the ballot last year instead, when the national environment favored Democrats by "only" 4.4 percent, they likely would have lost. Or, to put the matter more pointedly: Unless the Democratic nominee orchestrates an extraordinary landslide in 2024, Manchin and Tester will likely return to the private sector by mid-decade.

Meanwhile, attempts to mint new "Joe Manchins"--i.e., idiosyncratic Democrats whose strong local ties overwhelm the taint of the party's brand in white rural America--have invariably failed in the post-Trump era. Two years after Tester won reelection in Montana, the state's Democratic governor didn't come within ten points of winning his Senate race in 2020.

The party's outlook in the House of Representatives isn't much better. The abundance of predominantly white rural states doesn't just give Republicans an advantage in the Senate; it also gives them an advantage in fights over redistricting. Since there are more solidly red states than there are solidly blue ones, Republicans have more opportunities to gerrymander House maps than Democrats do. What's more, even in the absence of gerrymandering, the convention of drawing geographically compact districts naturally underrepresents Democrats, since their support is more geographically concentrated in urban centers than the GOP's support is in low-density areas.

This is one reason why Democrats lost House seats in the 2020 election. Now, with the new Census set to empower the GOP to produce an even more biased House map before 2022, Republicans have an excellent chance of retaking the House two years from now.

Making matters even more dire: (1) The Electoral College now has a four-point pro-GOP bias, meaning that if Biden wins the two-way popular vote by "only" 3.9 percent in 2024, he will have a less than 50 percent chance of winning reelection, and (2) the Republican Party has grown more openly contemptuous of democracy since Donald Trump's defeat. If the GOP does gain full control of the federal government in 2024, there is a significant risk it will further entrench its structural advantages through anti-democratic measures, so as to insulate right-wing minority rule against the threat of demographic change.

To defy political gravity, and fortify U.S. democracy against the threat of authoritarian reaction, Democrats need to either rebalance the electoral playing field through the passage of structural reforms, or attain a degree of popularity that no in-power party has achieved in modern memory. If the filibuster remains in place, doing the former will be impossible and the latter highly unlikely.

The Constitution limits the Democrats' capacity to correct the biases of America's governing institutions. But the party could significantly reduce the overrepresentation of white rural America in the Senate by granting statehood to the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and any other U.S. territory that wants it. The party could also prohibit partisan redistricting, ban felon disenfranchisement, erode practical barriers to the political participation of working-class people and immigrants, make it easier for workers to form unions (which are both good for democracy and Democrats), grant citizenship to 11 million undocumented immigrants, and pack the Supreme Court if it interferes with the implementation of these reforms.

To defy political gravity, and fortify U.S. democracy against the threat of authoritarian reaction, Democrats need to either rebalance the electoral playing field through the passage of structural reforms, or attain a degree of popularity that no in-power party has achieved in modern memory.

But none of those measures are going to attract ten Republican votes in the Senate. And none of them are achievable through the budget-reconciliation process.

If Democrats do not pass structural reforms, their odds of retaining both chambers of Congress in 2022 aren't good. The president's party almost always loses seats in midterms. And due to the GOP's structural advantages, even if Democrats replicated the Republican Party's post-9/11 performance in the 2002 elections--the only time this century that an in-power party gained ground--they might well still lose the House.

All this said, Democrats could have some extraordinary winds at their back. Biden has a decent shot of presiding over a post-pandemic economic boom. To the extent that Democrats can juice that recovery with further growth and wage-boosting measures--while maintaining the enthusiasm of their core interest groups--they may pull off the unprecedented in 2022.

But it's hard to see how the party can do that while leaving the filibuster fully intact. Democrats will be incapable of honoring their (now decade-old) IOUs to civil-rights organizations, labor unions, and immigrant communities if they allow the Senate's 60-vote threshold to remain in place. In a kinder political universe, Democratic control of the federal government would not be an aberration akin to a Buffalo Bills playoff win. In such a world, Democrats could pacify their core constituencies by pointing to the slimness of their current Senate majority and promising to deliver on their promises after they win more seats in 2022. In the world we actually live in, however, the NAACP and AFL-CIO have every reason to believe that this is the last Democratic trifecta they're going to see in some time.

Meanwhile, America's rising generations of millennials and zoomers--who are both more left wing than any of their predecessors and more distrustful of the major parties--are unlikely to grade the unified Democratic government on a curve. Keeping these cohorts invested in electoral politics, and rooted in "blue America," is vital to the Democratic Party's medium-term prospects. If the Biden presidency features two years of tepid reform followed by a midterm wipeout, younger, left-leaning voters may grow disaffected with electoral politics. (In this way, the GOP's structural advantages may be self-reinforcing: How many times can you watch your party win the popular vote but lose the election, and/or win the presidency but fail to govern, before you stop bothering to cast a ballot?)

All this makes it difficult for the Democratic leadership to accept the constraints that the filibuster, and the ideological orientation of its marginal senators, place on the prospects for reform.

Following Manchin and Sinema's remarks Monday night, Schumer assured reporters, "We are not letting McConnell dictate how the Senate operates." The majority leader then went on Maddow and vowed to pass major climate-, racial-justice-, and democracy-reform legislation. His office, meanwhile, declared victory in the standoff with McConnell and promised to get "big, bold things done for the American people."

In the immediate term, the Democrats' internal conflict over the filibuster will move to the backburner. Joe Biden's Covid-relief package and green-infrastructure "recovery" plan consist primarily of tax-and-spending measures that the party can advance through the budget-reconciliation process. And Schumer has signaled that he intends to bend the rules of that process as far as the Senate parliamentarian will let him, arguing that both a ban on new vehicles with internal-combustion engines and a $15 minimum wage are actually, primarily means of reducing government spending, when you really think about it.

But once reconciliation is done, attention will turn to the large stack of Democratic-coalition priorities that are currently subject to a 60-vote requirement. It will not be easy for Schumer to tell the NAACP that his caucus values a "Senate tradition" (that is anti-constitutional, historically associated with Jim Crow rule, and less than two decades old in its present form) more than it values a new Voting Rights Act. Nor will it be easy for the majority leader to tell organized labor that it will just have to wait until next time to see a $15 minimum wage (assuming that doesn't get through reconciliation) or collective-bargaining reform. And it might be hard for Schumer to accept that he probably won't ever wield majority power again after 2022 because his caucus would rather maintain the GOP's structural advantage in the upper chamber than abolish the filibuster and add new states.

It might be hard for Schumer to accept that he probably won't ever wield majority power again after 2022 because his caucus would rather maintain the GOP's structural advantage in the upper chamber than abolish the filibuster and add new states.

For these reasons, Schumer, Senate Democrat Whip Dick Durbin, and Delaware senator (and Biden confidant) Chris Coons have all telegraphed an intention to eliminate the filibuster if McConnell obstructs their coalition's priorities. The apparent hope is that--while Manchin, Sinema, and a few others support the filibuster in the abstract--in the heat of a legislative battle over voting rights or a $15 minimum wage, they may consent to weakening the filibuster while lamenting what Mitch McConnell is making them do.

Sinema and Manchin have repeatedly insisted that they will not "eliminate" or "get rid of" the filibuster. But there are plenty of ways to erode the Senate's 60-vote requirement that stop short of filibuster abolition. You could create new exemptions, modeled on budget reconciliation, that allow for the passage of certain categories of legislation by simple majority vote. Or you could restore the requirement for those mounting a filibuster to speak continuously from the Senate floor. Or you could throw every Democratic priority into a reconciliation bill and then let Kamala Harris overrule the parliamentarian when she objects.

But Manchin & Co.'s cooperation with this scheme is far from assured. The Democratic Party has a vital interest in passing sweeping reforms that gratify its base and mitigate its structural disadvantages. But Joe Manchin doesn't necessarily have an interest in the institutional health of the Democratic Party.

Our Republic's founders famously disdained political parties. And partisanship is a pejorative in contemporary American discourse. But our democracy's present affliction lies in the weakness of its parties, not in their strength. Were the GOP a stronger institution, the Trump presidency would never have happened. Were the Democratic leadership capable of formulating and enforcing a party line, the filibuster would not be long for this Earth.

While the Constitution failed to stymie the advent of political parties, it has kept them weaker than their overseas analogs. The Democratic Party is more of a loose association of elected officeholders than a coherent mass-member organization. As such, it has limited capacity to dictate terms to any of its incumbent senators, let alone to those whose job security would be enhanced by becoming Republicans. If Joe Manchin votes to abolish the filibuster, he will increase his personal power--but also likely expose himself to a series of "can't win" votes on legislation that divides his idiosyncratic voting base of Democrats and right-leaning independents. A strong Democratic Party might be capable of brokering a deal between its moderate senators, interest groups, and activists (e.g., "We'll abolish the filibuster if you'll focus your advocacy on a discrete set of mutually agreeable issues and pork for our home states"). The existing Democratic Party probably can't.

Thus the Democrats' existential interest in eroding the filibuster remains on a collision course with its moderate senators' aversion to power. Anyone with a fondness for democracy must hope that, against all odds, the forces of partisanship will prevail.

Joe Manchin said Monday that he will not, under any circumstances, "vote to get rid of the filibuster." Kyrsten Sinema echoed her West Virginia colleague. Mitch McConnell took the Democratic senators at their word.

But that doesn't necessarily mean that you should.

For the Democratic Party as an institution, the stakes of enacting major reforms over the next two years are nearly existential. And its leadership appears to understand this, even if its marginal senators do not.

The newly elected Senate is divided 50-50 between members of the Republican and Democratic caucuses. Vice-President Kamala Harris's tie-breaking vote gives Chuck Schumer an effective majority. But the even split within the upper chamber provided McConnell with an opportunity to throw the new Senate into dysfunction before it had even begun: In order to seat the body's new committee members, McConnell and Schumer had to reach consensus on a "power-sharing agreement."

As part of this agreement, the minority leader demanded that Democrats include a written commitment to preserve the legislative filibuster, the Senate rule that has established a de facto 60-vote threshold for the passage of all major bills. Schumer refused. The Senate ground to a halt.

As a constitutional matter, Senate majorities boast sovereignty over their chamber. Even if Democrats acquiesced to McConnell's demand, it would have remained within their power to change the rules on a party-line basis later in the term. But surrender would have made pulling such an about-face a tad more politically difficult. More importantly, it would have made it harder for Schumer to wield the threat of filibuster abolition as a cudgel in negotiations with Republicans over Biden's legislative agenda. Manchin, for his part, seemed to understand this, as Reuters reported last week:

Moderate Democrats like Senator Joe Manchin favor keeping the legislative filibuster. But even Manchin supports Schumer sticking to his guns and not making any promises to McConnell, keeping the threat of going "nuclear" on legislation in reserve if Republicans do not work cooperatively.

"Chuck has the right to do what he's doing," Manchin told reporters this week. "He has the right to use that to leverage in whatever he wants to do."

And yet, on Monday night, Manchin appeared to take that leverage out of Schumer's hands by voicing unconditional, unequivocal support for preserving the filibuster:

"If I haven't said it very plain, maybe Sen. McConnell hasn't understood, I want to basically say it for you. That I will not vote in this Congress, that's two years, right? I will not vote" to change the filibuster, Manchin (D-W.Va.) said...Asked if there is any scenario that would change his mind, he replied: "None whatsoever that I will vote to get rid of the filibuster."

McConnell decided to declare that this press report was an unofficial addendum to the Senate's power-sharing agreement--and that he was, therefore, the winner of the standoff. (In reality, McConnell was likely looking for an exit ramp, as maintaining the status quo meant denying his new members their committee assignments.)

For Democrats who would prefer for their party to not squander its first chance to govern in a decade (and/or last chance to avert America's descent into semi-permanent minority rule), hope now lies in the incoherence of Manchin's position: If the West Virginia senator is as unconditionally opposed to altering the filibuster as his recent remarks suggest, then it is not clear why he supported Schumer holding the line against McConnell's demand in the first place, much less why he would suggest that doing so provides the majority leader with "leverage."

This may seem like a rather thin reed on which to hang high hopes. And it is. But if the outlook for filibuster abolition looks dim, Blue America's civil war over the issue is far from over. For the Democratic Party as an institution, the stakes of enacting major reforms over the next two years are nearly existential. And its leadership appears to understand this, even if its marginal senators do not (and/or care not for their party's fate).

The basic problem facing the Democratic Party is simple: Barring an extraordinary change to America's political landscape, it will lose control of Congress in 2022 and have a difficult time regaining control for a decade thereafter.

To be sure, the assumption that existing political trends will continue indefinitely has been leading pundits astray since the advent of our loathsome profession. And in certain respects, the future of our politics looks more uncertain than at any time in recent memory. For example, the fact that a critical mass of Republican voters now belong to the personality cult of a narcissistic con man--who has no real investment in the conservative movement's well-being--makes the prospect of the GOP fracturing more thinkable than it's been in about a century.

This said, the trends bedeviling Democrats have been in motion for decades and are rooted in America's most durable political divides. To summarize the party's predicament: As a result of 19th-century efforts to gerrymander the Senate, the middle of our country is chock full of heavily white, low-population, rural states. This has always been a problem for the party of urban America--by boasting stronger support in rural areas, Republicans have long punched above their weight in the race for control of state governments and the Senate. But for most of the 20th century, this advantage was mitigated by the Democrats' (1) vestigial support in the post-Confederate South and (2) ability to render local issues more salient than national ones in Senate elections. Over the past two decades, however, urban-rural polarization in U.S. politics has reached unprecedented heights, while the collapse of local journalism and rise of the internet has made all politics national. Voters have never been less likely to split their tickets, and white rural areas have never been more likely to vote for Republicans. This is plausibly because the (irreversible, internet-induced) nationalization of politics has increased rural white voters' awareness of the myriad ways that urban, college-educated Democrats differ from them culturally. If this is the case, then the Democratic Party may have only a limited ability to reverse urban-rural polarization in the near-term future.

It took a series of minor miracles for the party to eke out its current 50-vote majority. By coincidence, Democrats happened to have their most vulnerable incumbent senators on the ballot two years ago, when the party rode anti-Trump fervor to one of the largest midterm landslides in American history. And yet: Winning the House popular vote by 8.6 percent was not sufficient to prevent the party from losing Senate seats. And although Jon Tester and Joe Manchin won reelection in their deep-red states, both underperformed the national environment: In a year when the nation as a whole favored Democrats by more than eight points, both Democratic incumbents won their races by a bit over three points. Which is to say, had those senators been on the ballot last year instead, when the national environment favored Democrats by "only" 4.4 percent, they likely would have lost. Or, to put the matter more pointedly: Unless the Democratic nominee orchestrates an extraordinary landslide in 2024, Manchin and Tester will likely return to the private sector by mid-decade.

Meanwhile, attempts to mint new "Joe Manchins"--i.e., idiosyncratic Democrats whose strong local ties overwhelm the taint of the party's brand in white rural America--have invariably failed in the post-Trump era. Two years after Tester won reelection in Montana, the state's Democratic governor didn't come within ten points of winning his Senate race in 2020.

The party's outlook in the House of Representatives isn't much better. The abundance of predominantly white rural states doesn't just give Republicans an advantage in the Senate; it also gives them an advantage in fights over redistricting. Since there are more solidly red states than there are solidly blue ones, Republicans have more opportunities to gerrymander House maps than Democrats do. What's more, even in the absence of gerrymandering, the convention of drawing geographically compact districts naturally underrepresents Democrats, since their support is more geographically concentrated in urban centers than the GOP's support is in low-density areas.

This is one reason why Democrats lost House seats in the 2020 election. Now, with the new Census set to empower the GOP to produce an even more biased House map before 2022, Republicans have an excellent chance of retaking the House two years from now.

Making matters even more dire: (1) The Electoral College now has a four-point pro-GOP bias, meaning that if Biden wins the two-way popular vote by "only" 3.9 percent in 2024, he will have a less than 50 percent chance of winning reelection, and (2) the Republican Party has grown more openly contemptuous of democracy since Donald Trump's defeat. If the GOP does gain full control of the federal government in 2024, there is a significant risk it will further entrench its structural advantages through anti-democratic measures, so as to insulate right-wing minority rule against the threat of demographic change.

To defy political gravity, and fortify U.S. democracy against the threat of authoritarian reaction, Democrats need to either rebalance the electoral playing field through the passage of structural reforms, or attain a degree of popularity that no in-power party has achieved in modern memory. If the filibuster remains in place, doing the former will be impossible and the latter highly unlikely.

The Constitution limits the Democrats' capacity to correct the biases of America's governing institutions. But the party could significantly reduce the overrepresentation of white rural America in the Senate by granting statehood to the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and any other U.S. territory that wants it. The party could also prohibit partisan redistricting, ban felon disenfranchisement, erode practical barriers to the political participation of working-class people and immigrants, make it easier for workers to form unions (which are both good for democracy and Democrats), grant citizenship to 11 million undocumented immigrants, and pack the Supreme Court if it interferes with the implementation of these reforms.

To defy political gravity, and fortify U.S. democracy against the threat of authoritarian reaction, Democrats need to either rebalance the electoral playing field through the passage of structural reforms, or attain a degree of popularity that no in-power party has achieved in modern memory.

But none of those measures are going to attract ten Republican votes in the Senate. And none of them are achievable through the budget-reconciliation process.

If Democrats do not pass structural reforms, their odds of retaining both chambers of Congress in 2022 aren't good. The president's party almost always loses seats in midterms. And due to the GOP's structural advantages, even if Democrats replicated the Republican Party's post-9/11 performance in the 2002 elections--the only time this century that an in-power party gained ground--they might well still lose the House.

All this said, Democrats could have some extraordinary winds at their back. Biden has a decent shot of presiding over a post-pandemic economic boom. To the extent that Democrats can juice that recovery with further growth and wage-boosting measures--while maintaining the enthusiasm of their core interest groups--they may pull off the unprecedented in 2022.

But it's hard to see how the party can do that while leaving the filibuster fully intact. Democrats will be incapable of honoring their (now decade-old) IOUs to civil-rights organizations, labor unions, and immigrant communities if they allow the Senate's 60-vote threshold to remain in place. In a kinder political universe, Democratic control of the federal government would not be an aberration akin to a Buffalo Bills playoff win. In such a world, Democrats could pacify their core constituencies by pointing to the slimness of their current Senate majority and promising to deliver on their promises after they win more seats in 2022. In the world we actually live in, however, the NAACP and AFL-CIO have every reason to believe that this is the last Democratic trifecta they're going to see in some time.

Meanwhile, America's rising generations of millennials and zoomers--who are both more left wing than any of their predecessors and more distrustful of the major parties--are unlikely to grade the unified Democratic government on a curve. Keeping these cohorts invested in electoral politics, and rooted in "blue America," is vital to the Democratic Party's medium-term prospects. If the Biden presidency features two years of tepid reform followed by a midterm wipeout, younger, left-leaning voters may grow disaffected with electoral politics. (In this way, the GOP's structural advantages may be self-reinforcing: How many times can you watch your party win the popular vote but lose the election, and/or win the presidency but fail to govern, before you stop bothering to cast a ballot?)

All this makes it difficult for the Democratic leadership to accept the constraints that the filibuster, and the ideological orientation of its marginal senators, place on the prospects for reform.

Following Manchin and Sinema's remarks Monday night, Schumer assured reporters, "We are not letting McConnell dictate how the Senate operates." The majority leader then went on Maddow and vowed to pass major climate-, racial-justice-, and democracy-reform legislation. His office, meanwhile, declared victory in the standoff with McConnell and promised to get "big, bold things done for the American people."

In the immediate term, the Democrats' internal conflict over the filibuster will move to the backburner. Joe Biden's Covid-relief package and green-infrastructure "recovery" plan consist primarily of tax-and-spending measures that the party can advance through the budget-reconciliation process. And Schumer has signaled that he intends to bend the rules of that process as far as the Senate parliamentarian will let him, arguing that both a ban on new vehicles with internal-combustion engines and a $15 minimum wage are actually, primarily means of reducing government spending, when you really think about it.

But once reconciliation is done, attention will turn to the large stack of Democratic-coalition priorities that are currently subject to a 60-vote requirement. It will not be easy for Schumer to tell the NAACP that his caucus values a "Senate tradition" (that is anti-constitutional, historically associated with Jim Crow rule, and less than two decades old in its present form) more than it values a new Voting Rights Act. Nor will it be easy for the majority leader to tell organized labor that it will just have to wait until next time to see a $15 minimum wage (assuming that doesn't get through reconciliation) or collective-bargaining reform. And it might be hard for Schumer to accept that he probably won't ever wield majority power again after 2022 because his caucus would rather maintain the GOP's structural advantage in the upper chamber than abolish the filibuster and add new states.

It might be hard for Schumer to accept that he probably won't ever wield majority power again after 2022 because his caucus would rather maintain the GOP's structural advantage in the upper chamber than abolish the filibuster and add new states.

For these reasons, Schumer, Senate Democrat Whip Dick Durbin, and Delaware senator (and Biden confidant) Chris Coons have all telegraphed an intention to eliminate the filibuster if McConnell obstructs their coalition's priorities. The apparent hope is that--while Manchin, Sinema, and a few others support the filibuster in the abstract--in the heat of a legislative battle over voting rights or a $15 minimum wage, they may consent to weakening the filibuster while lamenting what Mitch McConnell is making them do.

Sinema and Manchin have repeatedly insisted that they will not "eliminate" or "get rid of" the filibuster. But there are plenty of ways to erode the Senate's 60-vote requirement that stop short of filibuster abolition. You could create new exemptions, modeled on budget reconciliation, that allow for the passage of certain categories of legislation by simple majority vote. Or you could restore the requirement for those mounting a filibuster to speak continuously from the Senate floor. Or you could throw every Democratic priority into a reconciliation bill and then let Kamala Harris overrule the parliamentarian when she objects.

But Manchin & Co.'s cooperation with this scheme is far from assured. The Democratic Party has a vital interest in passing sweeping reforms that gratify its base and mitigate its structural disadvantages. But Joe Manchin doesn't necessarily have an interest in the institutional health of the Democratic Party.

Our Republic's founders famously disdained political parties. And partisanship is a pejorative in contemporary American discourse. But our democracy's present affliction lies in the weakness of its parties, not in their strength. Were the GOP a stronger institution, the Trump presidency would never have happened. Were the Democratic leadership capable of formulating and enforcing a party line, the filibuster would not be long for this Earth.

While the Constitution failed to stymie the advent of political parties, it has kept them weaker than their overseas analogs. The Democratic Party is more of a loose association of elected officeholders than a coherent mass-member organization. As such, it has limited capacity to dictate terms to any of its incumbent senators, let alone to those whose job security would be enhanced by becoming Republicans. If Joe Manchin votes to abolish the filibuster, he will increase his personal power--but also likely expose himself to a series of "can't win" votes on legislation that divides his idiosyncratic voting base of Democrats and right-leaning independents. A strong Democratic Party might be capable of brokering a deal between its moderate senators, interest groups, and activists (e.g., "We'll abolish the filibuster if you'll focus your advocacy on a discrete set of mutually agreeable issues and pork for our home states"). The existing Democratic Party probably can't.

Thus the Democrats' existential interest in eroding the filibuster remains on a collision course with its moderate senators' aversion to power. Anyone with a fondness for democracy must hope that, against all odds, the forces of partisanship will prevail.