Even before Joe Biden was sworn in on January 20, many of the President-elect's Congressional allies showed a willingness to embrace the same cautious approach to governing that had defined Biden's fifty-year career as a centrist with a marked aversion to going big for economic and racial justice, for peace, or for the planet.

If Biden and Congressional Democrats do not reset their course quickly, a toxic mix of centrist messaging and policy compromises will prove to be a recipe for political disaster.

Throughout the fall campaign that culminated in his election, Biden made it a point to explain how he'd beaten the party's progressive wing in securing the Democratic nomination to take on Donald Trump. "I'm the guy who ran against the socialists," he boasted.

Biden's bid for the presidency was, too frequently, framed around the promise of a return to normalcy. That was a predictably appealing campaign message after four years of racism, xenophobia, and neo-fascist scheming by a rogue President who would finish his term inciting a mob of supporters to storm the U.S. Capitol. Unfortunately, in the weeks after the campaign finished, the circumspect messaging continued. Indications from a bureaucratic Biden transition team--along with the Congressional leaders who would carry the new President's agenda in the House and Senate--suggested that Democrats were still seeking to manage the status quo rather than embrace fundamental change.

This tepid approach reflects a dangerous misread of the 2020 election results, as Biden begins his presidency with narrow Democratic majorities in the House and Senate. Polling data and election results--especially from referendums where progressive policies earned overwhelming support--bolster Congressional Progressive Caucus Chair Pramila Jayapal's argument that this is the morally, practically, and politically right time to fight for "a progressive agenda that makes a transformative difference in people's lives."

Yet caution prevails as the Democratic Party wrestles with whether to push for fundamental change or beat a retreat toward what passed for "normalcy" before Donald Trump and COVID-19 exposed the vulnerability of the American experiment.

If Biden and Congressional Democrats do not reset their course quickly, a toxic mix of centrist messaging and policy compromises will prove to be a recipe for political disaster. It will cost the party control of the House and Senate in 2022 and the presidency in 2024. It will also fail the American people at a time when there is a pressing, desperate need for bold responses to COVID-19, mass unemployment, the climate crisis, and the unanswered cries for racial justice.

The reality of the current crises--not a single crisis but many intersecting ones--make it absolutely clear that Biden and the Democrats must learn from the past seventy-five years of Democratic missteps and adopt a boldly progressive approach capable of meeting the challenges of the moment and capturing the imagination of a battered and beaten-down American electorate.

Regrettably, there are signs that the Democrats could make the same mistake--again.

In the waning days of the deeply divided and often dysfunctional 116th Congress, top Democrats stared into the face of the future and blinked.

Three weeks before the end of a year that had imposed untold pain on a great mass of Americans, the nation's most prominent progressive, Bernie Sanders, determined to make a last stand for families that were struggling to get by in the face of the coronavirus pandemic and the economic misery that extended from it.

Now is the time to write new rules, outline new policies, and dream new dreams.

Sanders marched onto the floor of the United States Senate on December 10, 2020, and declared: "Today, as a result of the horrific pandemic and economic meltdown, the American working class is hurting like they have never hurt before." He noted that more than 3,000 men, women, and children had died from the virus the day before. "In other words," he said, "more Americans were killed by the coronavirus yesterday than were killed on 9/11."

The democratic socialist from Vermont continued: "The working class of this country is in the worst financial shape since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Tens of millions of our fellow citizens have lost their jobs. They have lost their incomes. They have lost their health insurance. They have depleted their life savings. They cannot afford to pay the rent. They cannot afford to put food on the table. And they are scared to death that any day now they will get a knock on the door from the sheriff evicting them from their homes and throwing them and their belongings out on the street."

To address the crisis, Sanders announced that he was introducing an amendment to provide every working-class adult in the country with a $1,200 direct cash payment, plus $500 for each child. It was not a radical idea. A close ally of Sanders, California Representative Ro Khanna, had since April been advocating for a far bolder proposal to provide a $2,000 monthly payment to every qualifying American over the age of sixteen until the pandemic and the economic turbulence associated with it has passed.

Others on the left of the Democratic Party, particularly Jayapal, had outlined ambitious U.S. variations on the programs European countries used to keep workers on the job and businesses afloat. Meanwhile, Minnesota Representative Ilhan Omar proposed a moratorium on rent and mortgage payments to prevent evictions, and Michigan Representative Rashida Tlaib pushed to boost the maximum Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefit by 15 percent to combat hunger. Sanders simply sought to do again what Democrats and Republicans had done in March.

As the negotiations on 2020's final COVID-19 relief bill proceeded, however, the plan to provide working Americans with stimulus checks was nowhere to be found amid the slurry of bailouts for corporations and benefits for the wealthy. Sanders pushed on, with an unlikely Republican co-sponsor, Trump-aligned Missouri Senator Josh Hawley, a 2024 presidential prospect who in January would help lead an attempted coup against U.S. democracy.

But top Democrats, in full compromise mode, refused to go big on payments, eventually settling for a stingy $600 payment and a constrained extension on unemployment benefits. Then Trump suddenly proposed a $2,000 payment, and Democratic leaders, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Democrat of California, and then-Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, Democrat of New York, took up the proposal.

In the end, Democrats ended up supporting a compromise plan for the $600 payments that then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky, had negotiated.

Trump's motivation was easy to see. An embattled and embarrassed President pursuing a futile attempt to overturn the presidential election results wanted to do something that was popular and broadly understood as necessary. No mystery there.

But why hadn't Biden and other Democratic leaders jumped to embrace the Sanders plan? Why hadn't they used the interregnum between the election and the Inauguration to seize the moral and practical high ground with the boldest possible proposals and an uncompromising commitment to advance them?

Why didn't Democrats embrace the progressive-populist agenda that polls show the American people want?

The answers to those questions can be found in the absolute determination of those who occupy the upper echelons of the Democratic Party to pull their punches.

Democratic Congressional leaders, Democratic National Committee chairs, consultants, strategists, and fundraisers practice a narrow-gauge politics that seeks to win on the margins rather than to win big. This approach appeals to wealthy campaign donors and corporate interests, which donate to both parties to maintain the neoliberal "consensus" that has held for much of the past forty years.

No one should underestimate the cynical motivations of party leaders who raise massive amounts of money for campaign treasuries that are now measured in the hundreds of millions and low billions.

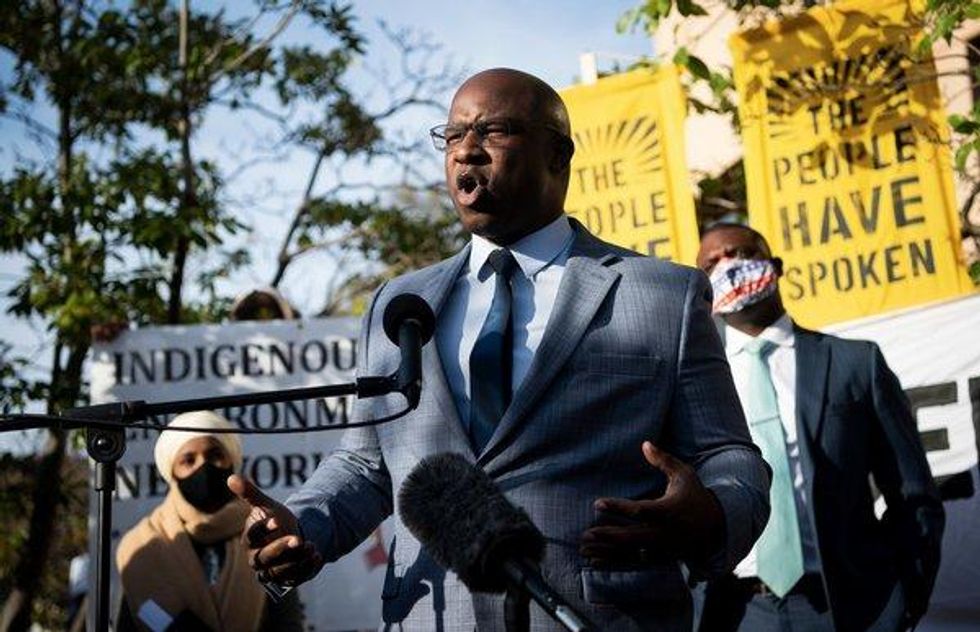

But there is more to it than that. Wall Street Democrats, who cloak their allegiance to big business in the mild language of centrism, have battled for decades to claim control of the Democratic Party. They are not inclined to give it up to self-declared "outsiders" such as Sanders, nor to an upstart generation of progressives such as New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (known as AOC) and the members of an ever-expanding "Squad" that now includes Omar, Tlaib, Massachusetts Representative Ayanna Pressley, Missouri Representative Cori Bush, New York Representative Jamaal Bowman, and a host of other challengers to the status quo.

The chaos in the Republican Party at the close of Trump's brutal presidency has obscured the fact that the Democratic Party is deeply divided. On one side are the centrist stalwarts, many with their hands on the levers of power and determined to continue with the cautious politics of former Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

On the other side are progressives who argue that the party must renew its commitment to the bolder vision of the Four Freedoms and an Economic Bill of Rights that former President Franklin D. Roosevelt amplified when the party gave the county a New Deal, a victory over fascism, and a twelve-year streak of presidential and midterm election wins for Democrats.

When AOC recalls the New Deal Democrats and says, "I want us to be that party again," she is not proposing a repeat of policies from the 1930s and 1940s. She is calling for a renewal of the old sense of possibility and the progressive-populist approach that extends from it.

The problem, as AOC explained after the 2020 election, is that the Democratic leadership keeps deferring to its most cautious members in a way that Republicans don't. The major difference between the GOP and the Democrats, AOC has said, is that Republicans "leverage their right flank to gain policy concessions and generate enthusiasm, while Dems lock their left flank in the basement [because] they think that will make Republicans be nicer to them."

This is what centrists demand.

Right after the 2020 election, when it became clear that Biden had won but that Democrats might not win in the Senate and have a narrower majority in the House, more-conservative Democrats raced to blame the left for the defeat of centrists running in so-called swing districts.

"We lost members who shouldn't have lost," Virginia Representative Abigail Spanberger, a former CIA operative, reportedly said during a post-election call with House Democrats. "Don't ever use the word socialist or socialism ever again," she added. "If we are classifying Tuesday as a success from a Congressional standpoint, we will get fucking torn apart in 2022."

Fox News gleefully reported that a Democratic source who listened in on the exchange said numerous members on the call complained that progressive rallying cries cost moderates their seats. "There's absolutely no accountability from the Speaker," it quoted one frustrated Democrat as saying. "We should have won big but, you know, the 'defund the police' issue, the Green New Deal. Those issues killed our members. Having everybody walk the plank on qualified immunity with the cops. That just hurt a lot of members."

This narrative was amplified across major media outlets. Immediately after Biden was declared the winner, former Ohio Governor John Kasich, a "Never Trump" Republican, appeared on CNN to declare: "The best thing that's happened to Joe Biden is the fact that the United States Senate is either going to be Republican or very close . . . . And the far left can push him as hard as they want. And frankly, the Democrats have to make it clear to the far left that they almost cost him this election."

That's nonsense. Yet, the argument persisted, as centrists and "Never Trump" Republicans kept complaining about the "damage" done to Democratic prospects by progressives who advocated for Medicare for All, a Green New Deal, and major reforms in policing. At the same time, a Fox News exit poll showed 70 percent of Americans favor "changing the health care system so that any American can buy into a government-run health care plan," 67 percent favor "increasing federal government spending on green and renewable energy," and 77 percent think racism in policing is a serious problem while 68 percent say the criminal justice system requires major changes--up to and including "a complete overhaul."

The truth is that mixed signals from Biden and other top Democrats caused far more damage than their advocacy for progressive policies. Throughout 2020, the party focused so much of its messaging on the worthy goal of defeating Trump that it underemphasized--and in some cases distanced itself from--popular ideas long advanced by progressives.

Consider what happened in Florida on November 3. Biden lost a state many thought he would win by more than 370,000 votes. Two Democratic members of the U.S. House were defeated, as were five Democratic incumbents in the state's lower house.

Yet on the same day, a Florida state initiative backed by unions and progressive groups to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour--a goal advanced by the left in states across the country over the past decade--won by almost 2.3 million votes, gaining support from nearly 61 percent of the electorate.

What explains this disconnect? Florida State Representative Anna Eskamani, a progressive Democrat from Orlando who took over a Republican-held seat in 2018 and was easily re-elected in 2020, noted that Democratic Party leaders failed to openly endorse the minimum-wage amendment, which was unpopular with corporate donors.

"If more Democrats ran with increasing the minimum wage, we would have won more seats," Eskamani declared on election night. She expressed her frustration with a party "scared to stand with working people because then the corporations that fund @FlaDems and so many candidates will get mad and stop throwing crumbs at us while they throw a LOT more at Republican Party and caucuses. We lose, the people lose--corporations win."

Eskamani's assessment was right, as was her observation that "without a doubt the Democratic Party needs to clean house. We keep using the same consultants, and none of the consultants are going to say anything because they are making money."

Yet Eskamani's fact-based analysis didn't get as much attention as Spanberger's F-bomb-laced outburst. Nor did Jayapal's observation that "progressive ballot initiatives also won across the country."

In Colorado, she noted, voters "passed twelve weeks of paid family leave while also rejecting an abortion ban. Four states, red and blue, legalized recreational marijuana. And Arizona raised taxes on the rich to increase funding for public education. Make no mistake: Voters approved a progressive agenda."

As AOC tweeted, "Every single swing-seat House Democrat who endorsed #MedicareForAll won re-election or is on track to win re-election. Every. Single. One."

The pressure on Biden and the Democrats to curb their enthusiasm is immense. It comes from the special interests that fund both parties.

These are people who know that, while a Green New Deal is needed to save the planet, tackling climate change will diminish the fortunes of fossil-fuel conglomerates. They know that, while Medicare for All is more necessary than ever in this COVID-19 moment, genuine health-care reform will undercut insurance- and pharmaceutical-industry profiteering.

They know that, while cutting Pentagon bloat will free up money for human needs, upending the Military-Industrial Complex will cut the cash flow to the defense contractors who write big checks at election time.

So it is that, when Abigail Spanberger warns that a progressive approach will cause Democrats to "get fucking torn apart in 2022," there are legions of party insiders, donors, consultants, and pundits who are all too ready to amplify that message. As Sanders told me, "The establishment will use any and every reason to attack progressive ideas, even when those ideas are enormously popular." But how should progressives respond?

Centrists start by saying that progressives must be realistic.

Fair enough. Let's be realistic. Let's talk about when Democrats have succeeded and when they have gotten torn apart over the past century.

Franklin D. Roosevelt was the last Democratic President who went from strength to strength. He defeated Republican Herbert Hoover in 1932 and went on to be re-elected--as a steadily more progressive candidate--in 1936, 1940, and 1944. His Congressional allies won the midterm elections of 1934, 1938, and 1942.

That perfect record of election victories was broken in 1946, when Republicans took control of both the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate for the first time since 1930. What happened? When Roosevelt died in April of 1945, he was succeeded by Harry Truman, a favorite of the big-city machine Democrats who deposed FDR's activist Vice President, Henry Wallace, at the 1944 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

While Wallace had argued that the only way for Democrats to keep winning was to "go down the line" for progressive policies, Truman was more closely aligned with the centrists who sought to reassert themselves after the Roosevelt years. Truman purged progressives from the administration with a vengeance and, by 1946, the Chicago Tribunereported that "the New Dealers are out and the Wall Streeters are in."

The Truman Administration's tepid, unfocused initial approach failed to capture the imagination of Americans who wanted, and needed, a new New Deal in the aftermath of the home-front sacrifices that had helped secure the Allied victory in World War II. Democrats lost their governing majority and Republicans, along with Southern segregationist Democrats, quickly began to undo the New Deal, starting with the Taft-Hartley Act's attack on labor rights.

Truman would scramble back to win a plurality of the vote in 1948, but the Democratic Party would never get its groove back.

FDR was the last Democratic President to win more than one election until Bill Clinton, who won the presidency in 1992 with solid Democratic majorities in the House and Senate. Unlike Roosevelt, however, Clinton failed to keep Democratic control of the Congress. Instead of governing as a bold progressive, Clinton worked with Republicans to pass free trade deals, spoke of how the era of big government was over, and upended New Deal social welfare protections and banking regulations. The Democrats lost control of both the House and Senate in 1994 and did not regain full control of Congress until 2006.

The Democrats also suffered severe setbacks at the state and local levels, paving the way for Republican gerrymandering schemes following the 2010 Census.

When Obama won the presidency in 2008, he had solid Democratic majorities in the House and Senate. But the centrist approach he took--at the urging of Wall Street-aligned Democrats such as Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, National Economic Council Director Lawrence Summers, and White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel--again undermined the Democratic coalition.

The party lost the House in the 2010 midterm election and the Senate in the 2014 midterm, denying Obama a Congress he could work with for six of his eight years in office.

Democrats cannot afford to repeat this pattern. Neither can the country. The defeat of Trump has opened up a range of possibilities for Biden and his party.

Now is the time to write new rules, outline new policies, and dream new dreams. The Democratic Party can harness the energy of the moment and deliver the relief needed by tens of millions of Americans.

But Democrats won't do that as cautious, compromising centrists. They can only do it with a bold progressive agenda that recognizes that health care is a right, that the planet must be saved, and that systemic racism must be eradicated.

As Sanders has said, "Maybe it's a time for the working class of this country to have a little bit of power in Washington, rather than your billionaire campaign contributors."