Du Bois, born February 23, 1868, wanted to build a democracy that respects the rights of all. (Photo: wikimedia commons / Public Domain)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Du Bois, born February 23, 1868, wanted to build a democracy that respects the rights of all. (Photo: wikimedia commons / Public Domain)

February 23 marked the birthday of William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, an intellectual giant who committed his life to advancing Black freedom in the US and abroad.

Born in Massachusetts in 1868, in the wake of the Civil War, Du Bois attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, a historically Black college, and became the first African American to earn a doctorate degree from Harvard University in 1895.

His massive corpus of work - from 'The Philadelphia Negro' to 'Black Reconstruction in America' - is a testament to his academic genius and desire for establishing a truly equitable society.

Now, as America faces a renewed time of political crisis and racial polarization, the words of Du Bois , which offer a vision for building a multi-racial democracy, are more relevant than ever.

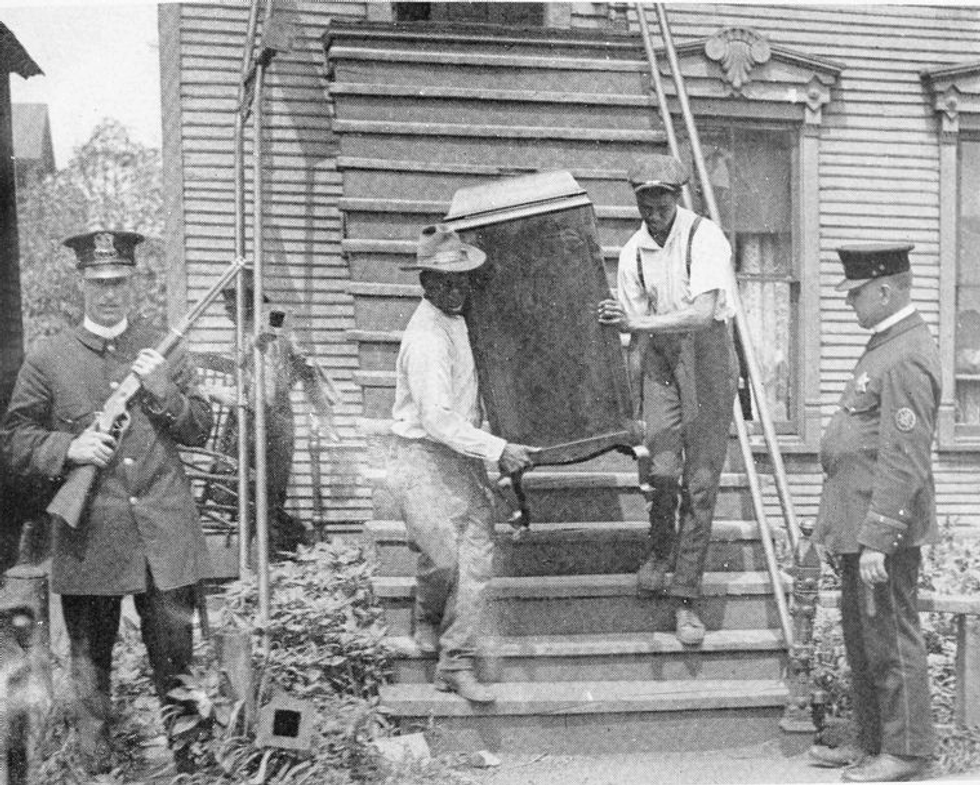

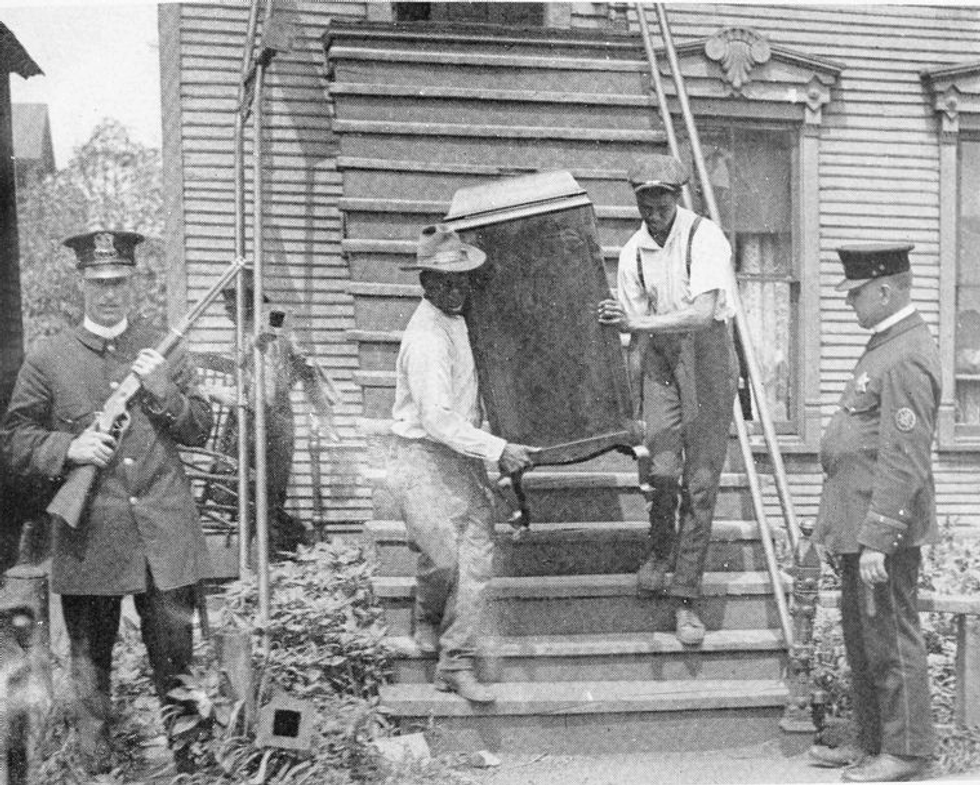

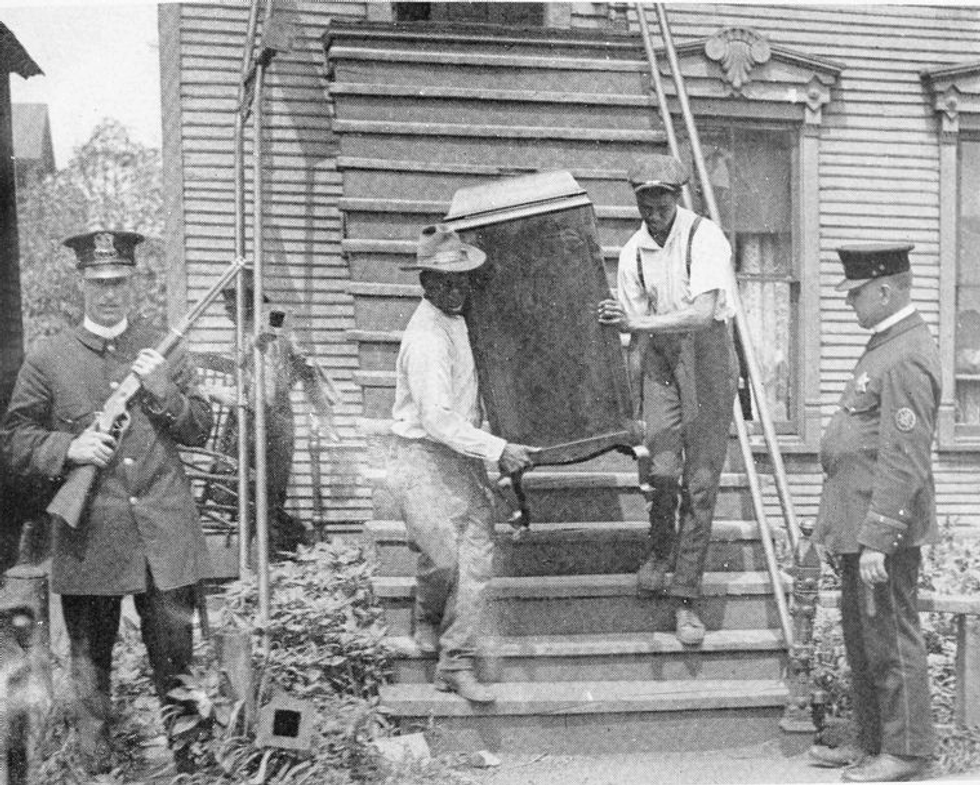

Du Bois's critique of American society, in works such as his 1910 essay 'The Souls of White Folk', is a reminder of the historical legacy of white supremacist violence in the US.

"Can you imagine the United States protesting against Turkish atrocities in Armenia, while the Turks are silent about mobs in Chicago and St. Louis; what is Louvain (the German massacre of Belgian citizens during the Great War) compared with Memphis, Waco, Washington, Dyersburg, and Estill Springs? In short, what is the black man but America's Belgium, and how could America condemn Germany that which she commits, just as brutally, within her own borders?"

Du Bois astutely reveals how mob violence has been used throughout history to prevent the expansion of democracy - which the US purports to fight for abroad.

Du Bois was intimately concerned about the fragility of American democracy.

His magnum opus, 'Black Reconstruction in America', first published in 1935, reveals just how close the US came to finally building a genuine multi-racial democracy in the wake of the Civil War.

The decade of Reconstruction, from 1867 to 1877, marked the establishment of a thriving Black civil society that included churches, primary and secondary schools, and the rise of a Black political class devoted to implementing universal social programs.

Du Bois's idea of "abolition democracy", coined in the pages of 'Black Reconstruction in America', outlines the central demands of this era for Black "physical freedom, civil rights, economic opportunity and education and the right to vote, [as a] a matter of sheer human justice and right".

However, this vision for full equity was ultimately defeated by a targeted campaign of physical violence, economic exploitation, and political neutering against Black Americans.

Now, as many activists and progressive politicians call for a new era of reconstruction, Du Bois's work demonstrates the importance of building a multi-racial working-class movement to achieve this vision of an equitable society - by warning of the destructive consequences of segregation.

Du Bois highlights how the period following Reconstruction was met by mass labor unrest, which had the potential to transform working-class conditions across the country.

Today, it is increasingly important that the US Left learns the lessons of Du Bois, and secures a diverse working-class coalition to defeat a resurgent white nationalism.For instance, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 nearly shut down the US economy, but the movement was stymied by a lack of solidarity across racial lines.

As Du Bois explains, "Labor went into the great war of 1877 against Northern capitalists unsupported by the black man, and the black man went his way in the South ... unsupported by Northern labor."

Today, it is increasingly important that the US Left learns the lessons of Du Bois, and secures a diverse working-class coalition to defeat a resurgent white nationalism. And the past year shows that there is reason for hope.

The Black Lives Matter protests following the police killing of George Floyd in May 2020 featured historic solidarity of people across racial lines, and the victory of Joe Biden in November's presidential election was powered principally by a multi-racial coalition.

No doubt, Du Bois would have recognized our moment of resurgent white nationalism and the type of mob violence seen at the US Capitol on 6 January as similar to - although not precisely the same - as that which broke the back of Reconstruction governments across the American south in the 1870s.

Building a genuine democracy that respects the rights of all was a cherished wish of Du Bois's. That we have failed to do so means that his writings - and his vision for the future influenced by an informed and nuanced recounting of the past - becomes all the more important today.

Donald Trump’s attacks on democracy, justice, and a free press are escalating — putting everything we stand for at risk. We believe a better world is possible, but we can’t get there without your support. Common Dreams stands apart. We answer only to you — our readers, activists, and changemakers — not to billionaires or corporations. Our independence allows us to cover the vital stories that others won’t, spotlighting movements for peace, equality, and human rights. Right now, our work faces unprecedented challenges. Misinformation is spreading, journalists are under attack, and financial pressures are mounting. As a reader-supported, nonprofit newsroom, your support is crucial to keep this journalism alive. Whatever you can give — $10, $25, or $100 — helps us stay strong and responsive when the world needs us most. Together, we’ll continue to build the independent, courageous journalism our movement relies on. Thank you for being part of this community. |

February 23 marked the birthday of William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, an intellectual giant who committed his life to advancing Black freedom in the US and abroad.

Born in Massachusetts in 1868, in the wake of the Civil War, Du Bois attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, a historically Black college, and became the first African American to earn a doctorate degree from Harvard University in 1895.

His massive corpus of work - from 'The Philadelphia Negro' to 'Black Reconstruction in America' - is a testament to his academic genius and desire for establishing a truly equitable society.

Now, as America faces a renewed time of political crisis and racial polarization, the words of Du Bois , which offer a vision for building a multi-racial democracy, are more relevant than ever.

Du Bois's critique of American society, in works such as his 1910 essay 'The Souls of White Folk', is a reminder of the historical legacy of white supremacist violence in the US.

"Can you imagine the United States protesting against Turkish atrocities in Armenia, while the Turks are silent about mobs in Chicago and St. Louis; what is Louvain (the German massacre of Belgian citizens during the Great War) compared with Memphis, Waco, Washington, Dyersburg, and Estill Springs? In short, what is the black man but America's Belgium, and how could America condemn Germany that which she commits, just as brutally, within her own borders?"

Du Bois astutely reveals how mob violence has been used throughout history to prevent the expansion of democracy - which the US purports to fight for abroad.

Du Bois was intimately concerned about the fragility of American democracy.

His magnum opus, 'Black Reconstruction in America', first published in 1935, reveals just how close the US came to finally building a genuine multi-racial democracy in the wake of the Civil War.

The decade of Reconstruction, from 1867 to 1877, marked the establishment of a thriving Black civil society that included churches, primary and secondary schools, and the rise of a Black political class devoted to implementing universal social programs.

Du Bois's idea of "abolition democracy", coined in the pages of 'Black Reconstruction in America', outlines the central demands of this era for Black "physical freedom, civil rights, economic opportunity and education and the right to vote, [as a] a matter of sheer human justice and right".

However, this vision for full equity was ultimately defeated by a targeted campaign of physical violence, economic exploitation, and political neutering against Black Americans.

Now, as many activists and progressive politicians call for a new era of reconstruction, Du Bois's work demonstrates the importance of building a multi-racial working-class movement to achieve this vision of an equitable society - by warning of the destructive consequences of segregation.

Du Bois highlights how the period following Reconstruction was met by mass labor unrest, which had the potential to transform working-class conditions across the country.

Today, it is increasingly important that the US Left learns the lessons of Du Bois, and secures a diverse working-class coalition to defeat a resurgent white nationalism.For instance, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 nearly shut down the US economy, but the movement was stymied by a lack of solidarity across racial lines.

As Du Bois explains, "Labor went into the great war of 1877 against Northern capitalists unsupported by the black man, and the black man went his way in the South ... unsupported by Northern labor."

Today, it is increasingly important that the US Left learns the lessons of Du Bois, and secures a diverse working-class coalition to defeat a resurgent white nationalism. And the past year shows that there is reason for hope.

The Black Lives Matter protests following the police killing of George Floyd in May 2020 featured historic solidarity of people across racial lines, and the victory of Joe Biden in November's presidential election was powered principally by a multi-racial coalition.

No doubt, Du Bois would have recognized our moment of resurgent white nationalism and the type of mob violence seen at the US Capitol on 6 January as similar to - although not precisely the same - as that which broke the back of Reconstruction governments across the American south in the 1870s.

Building a genuine democracy that respects the rights of all was a cherished wish of Du Bois's. That we have failed to do so means that his writings - and his vision for the future influenced by an informed and nuanced recounting of the past - becomes all the more important today.

February 23 marked the birthday of William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, an intellectual giant who committed his life to advancing Black freedom in the US and abroad.

Born in Massachusetts in 1868, in the wake of the Civil War, Du Bois attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, a historically Black college, and became the first African American to earn a doctorate degree from Harvard University in 1895.

His massive corpus of work - from 'The Philadelphia Negro' to 'Black Reconstruction in America' - is a testament to his academic genius and desire for establishing a truly equitable society.

Now, as America faces a renewed time of political crisis and racial polarization, the words of Du Bois , which offer a vision for building a multi-racial democracy, are more relevant than ever.

Du Bois's critique of American society, in works such as his 1910 essay 'The Souls of White Folk', is a reminder of the historical legacy of white supremacist violence in the US.

"Can you imagine the United States protesting against Turkish atrocities in Armenia, while the Turks are silent about mobs in Chicago and St. Louis; what is Louvain (the German massacre of Belgian citizens during the Great War) compared with Memphis, Waco, Washington, Dyersburg, and Estill Springs? In short, what is the black man but America's Belgium, and how could America condemn Germany that which she commits, just as brutally, within her own borders?"

Du Bois astutely reveals how mob violence has been used throughout history to prevent the expansion of democracy - which the US purports to fight for abroad.

Du Bois was intimately concerned about the fragility of American democracy.

His magnum opus, 'Black Reconstruction in America', first published in 1935, reveals just how close the US came to finally building a genuine multi-racial democracy in the wake of the Civil War.

The decade of Reconstruction, from 1867 to 1877, marked the establishment of a thriving Black civil society that included churches, primary and secondary schools, and the rise of a Black political class devoted to implementing universal social programs.

Du Bois's idea of "abolition democracy", coined in the pages of 'Black Reconstruction in America', outlines the central demands of this era for Black "physical freedom, civil rights, economic opportunity and education and the right to vote, [as a] a matter of sheer human justice and right".

However, this vision for full equity was ultimately defeated by a targeted campaign of physical violence, economic exploitation, and political neutering against Black Americans.

Now, as many activists and progressive politicians call for a new era of reconstruction, Du Bois's work demonstrates the importance of building a multi-racial working-class movement to achieve this vision of an equitable society - by warning of the destructive consequences of segregation.

Du Bois highlights how the period following Reconstruction was met by mass labor unrest, which had the potential to transform working-class conditions across the country.

Today, it is increasingly important that the US Left learns the lessons of Du Bois, and secures a diverse working-class coalition to defeat a resurgent white nationalism.For instance, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 nearly shut down the US economy, but the movement was stymied by a lack of solidarity across racial lines.

As Du Bois explains, "Labor went into the great war of 1877 against Northern capitalists unsupported by the black man, and the black man went his way in the South ... unsupported by Northern labor."

Today, it is increasingly important that the US Left learns the lessons of Du Bois, and secures a diverse working-class coalition to defeat a resurgent white nationalism. And the past year shows that there is reason for hope.

The Black Lives Matter protests following the police killing of George Floyd in May 2020 featured historic solidarity of people across racial lines, and the victory of Joe Biden in November's presidential election was powered principally by a multi-racial coalition.

No doubt, Du Bois would have recognized our moment of resurgent white nationalism and the type of mob violence seen at the US Capitol on 6 January as similar to - although not precisely the same - as that which broke the back of Reconstruction governments across the American south in the 1870s.

Building a genuine democracy that respects the rights of all was a cherished wish of Du Bois's. That we have failed to do so means that his writings - and his vision for the future influenced by an informed and nuanced recounting of the past - becomes all the more important today.