SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Workers iron the fabric used for the production of personal protective equipment for COVID-19 coronavirus frontline health workers as commissioned by the government, in Accra, on April 17, 2020. (Photo: Nipah Dennis/AFP via Getty Images)

For decades, we have been sold a myth of private health. It is a myth that our health is largely a product of individual choices and personal responsibilities. It is a myth that our healthcare is a service that private corporations can provide, and for which we must pay to survive.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has blown up this myth.

Our personal health cannot be separated from the health of our neighbors or our planet. Nor can it be separated from the structural factors and policy decisions that have determined our health outcomes long before we are born.

The right to health, in the context of these interconnections, is a universal right. Your life is worth no more and no less than that of your next-door neighbor because the fates of the two are so intimately entwined.

"Any strategy to reclaim public health for the public good must center social determinants and seek to increase public power across sectors of the economy responsible for the basic conditions of human life and the stability of our environment."

Today, the universal right to health is not held back by scarcity of resources or a lack of technology. On the contrary, the wealth of this world--invested well--could end the pandemic before the year's end.

Instead, we are held back by another myth: that there exists a trade-off between public health and the health of the economy. The assumption of this trade-off dictates that all public policy is subordinate to the great god of economic growth--even if it costs us our lives. The concept of private health grows out of this second myth, which makes a commodity of our bodies, and a market for essential healthcare services.

Indeed, public health systems around the world are structured carefully to serve a profit motive. Unsurprisingly, their outcomes are inequitable and insufficient, leaving poor and marginalized communities with no recourse to private health provision.

Drawing on the evidence of health impacts of the coronavirus pandemic and the impact of policy responses, the racial, gender and class dimension in the impact of the virus is undeniable. The raw reality of systemic fragility of both public health and economic systems in the North in dealing with the social crisis has also been brought to the fore. Those countries that have been successful--such as Vietnam, Cuba and New Zealand--viewed public health as economic wealth.

Once again, we return to the basic premise. Health, in all its dimensions, is a public good.

How can we deliver a world that reflects this simple premise?

The first step is decolonization. Countries in the Global South cannot deliver on the promise of public health when they are curtailed by neocolonial conditionalities that come along with philanthropic funding and multilateral lending. This top-down approach strips countries of their sovereignty over how to fund health services, privatizes health infrastructure and cripples social policy provisions.

Most of these countries assured universal health services as a matter of course in the 1960s and 1970s. Then came structural adjustment. The imposition of the Washington Consensus in the course of the 1980s and 1990s led to a radical reframing of the health sector as a profitable site of privatization and deregulation. The introduction of user fees and prioritization of imported, high tech-fixes forced millions of poor people to the margins, as "private health" became the norm. Provision in the form of "minimum packages" took priority over comprehensive primary and community health.

Public health, then, requires public ownership--a form of ownership that can deliver transparency and foster citizen participation in the delivery of healthcare services. Public sector clinics, homecare companies, and biomedical enterprises should be built to assure the production and distribution of essential medicines and medical technologies as well as healthcare services.

Free from the structural constraints of shareholder primacy and profit maximization, these enterprises will be able to prioritize preventative and curative technologies, fill gaps in existing treatments, and provide products at or below cost where necessary to meet public health needs.

Moreover, they can return revenue to public balance sheets, reduce inefficiencies, and create surge capacity for emergencies. Having a robust public sector infrastructure for the development, manufacture, and distribution of essential goods like medicines, personal protective equipment, and other medical instruments breaks the corporate monopoly over our supply of medical goods, reducing regulatory capture and increasing public power to demand equitable and universal access to critical health goods and services.

Health as a public good offers positive externalities for the economy and society. Even if we just follow the logic of narrow economic growth, a dollar investment in health in developing countries is estimated to result in between $2 and $4 in economic returns over time. And those dollars are best spent when communities and nations have the autonomy to prioritize their own needs and invest in long-term institution-building that will serve their communities for years to come.

Countries like Cuba and Vietnam have demonstrated that, even with modest budgets, developing a sovereign healthcare system that prioritizes primary and preventative care together with robust public health infrastructure can deliver first-rate population health outcomes. [Investing in public healthcare systems has been shown to contribute to better outcomes] than investing in privatized healthcare systems. Freeing the healthcare sector from market imperatives would allow for the recentering of primary and preventative care, planning for equitable access, and robust community health outreach--not traditionally the profit-making parts of healthcare delivery. Additionally, targeted workforce development programs can be created to meet community needs while providing stable, public sector jobs that are themselves an upstream investment in community health.

Reclaiming autonomy of the public sector by sovereign nations requires a shift from the current donor-driven vertical disease control programs most funded in prioritizing the needs of the community. Vertical interventions to eradicate single diseases are often costly and have been imposed on low and middle-income countries at the expense of horizontal enhancements of public health infrastructure that would serve whole populations over the long term and make local health systems more resilient. They also contribute to internal brain drain with skilled people leaving the public sector to work for higher pay in international and nongovernmental organizations.

"The COVID-19 pandemic has opened a window of opportunity to revisit and reevaluate the many myths that held up a broken system of global health. And in doing so, it has offered us the chance to deliver a truly global public health system: equitable, inclusive and people-centered."

Reversal of structural adjustment conditions and untying loans, donor grants and external funding from conditionalities is essential in reclaiming sovereignty in the national public health decision space. Complete restructuring of the global health governance mechanisms to ensure democratic representation in decision-making by every participating country, whether they are net donors or net recipients, is vital. Global health governance mechanisms must have measures in place to ensure that external influence exerted over countries is subordinate to national sovereignty, and that the activities of global health organizations without a democratic mandate are overseen and their impact held to account by national governments.

Representation of the most marginalized and communities most impacted by colonialism and structural adjustment on governance of global health and financial institutions is important for their priorities and perspectives to be included on the agenda and in development priorities. In addition, more community empowerment, participation, and co-planning in the process of deprivatization of healthcare services can aid in the democratization of healthcare and provide increased opportunities for transparency, citizen accountability, and oversight.

Hand-in-hand with the reclaiming of the healthcare sector for the public good should be the reclamation of essential services like water and power. Investments in public power and water--coupled with divestments from fossil fuels--would build both climate resilience and more equitable access to the basic infrastructure of public health. Amongst the greatest challenges to public health in many countries around the world are still infectious diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, and lower respiratory infections, all of which correlate highly to social determinants like access to clean water and good living conditions, air quality, and sanitation. Any strategy to reclaim public health for the public good must center social determinants and seek to increase public power across sectors of the economy responsible for the basic conditions of human life and the stability of our environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic has opened a window of opportunity to revisit and reevaluate the many myths that held up a broken system of global health. And in doing so, it has offered us the chance to deliver a truly global public health system: equitable, inclusive and people-centered.

A withering critique of capitalism is not enough. It is time to reimagine a world where human life and environmental sustainability are the first priority, and where that universal right to health is the basis for all public policy.

A system premised on this universal right--and powered by global solidarity--is not only possible. For our species to survive, it is necessary.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

For decades, we have been sold a myth of private health. It is a myth that our health is largely a product of individual choices and personal responsibilities. It is a myth that our healthcare is a service that private corporations can provide, and for which we must pay to survive.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has blown up this myth.

Our personal health cannot be separated from the health of our neighbors or our planet. Nor can it be separated from the structural factors and policy decisions that have determined our health outcomes long before we are born.

The right to health, in the context of these interconnections, is a universal right. Your life is worth no more and no less than that of your next-door neighbor because the fates of the two are so intimately entwined.

"Any strategy to reclaim public health for the public good must center social determinants and seek to increase public power across sectors of the economy responsible for the basic conditions of human life and the stability of our environment."

Today, the universal right to health is not held back by scarcity of resources or a lack of technology. On the contrary, the wealth of this world--invested well--could end the pandemic before the year's end.

Instead, we are held back by another myth: that there exists a trade-off between public health and the health of the economy. The assumption of this trade-off dictates that all public policy is subordinate to the great god of economic growth--even if it costs us our lives. The concept of private health grows out of this second myth, which makes a commodity of our bodies, and a market for essential healthcare services.

Indeed, public health systems around the world are structured carefully to serve a profit motive. Unsurprisingly, their outcomes are inequitable and insufficient, leaving poor and marginalized communities with no recourse to private health provision.

Drawing on the evidence of health impacts of the coronavirus pandemic and the impact of policy responses, the racial, gender and class dimension in the impact of the virus is undeniable. The raw reality of systemic fragility of both public health and economic systems in the North in dealing with the social crisis has also been brought to the fore. Those countries that have been successful--such as Vietnam, Cuba and New Zealand--viewed public health as economic wealth.

Once again, we return to the basic premise. Health, in all its dimensions, is a public good.

How can we deliver a world that reflects this simple premise?

The first step is decolonization. Countries in the Global South cannot deliver on the promise of public health when they are curtailed by neocolonial conditionalities that come along with philanthropic funding and multilateral lending. This top-down approach strips countries of their sovereignty over how to fund health services, privatizes health infrastructure and cripples social policy provisions.

Most of these countries assured universal health services as a matter of course in the 1960s and 1970s. Then came structural adjustment. The imposition of the Washington Consensus in the course of the 1980s and 1990s led to a radical reframing of the health sector as a profitable site of privatization and deregulation. The introduction of user fees and prioritization of imported, high tech-fixes forced millions of poor people to the margins, as "private health" became the norm. Provision in the form of "minimum packages" took priority over comprehensive primary and community health.

Public health, then, requires public ownership--a form of ownership that can deliver transparency and foster citizen participation in the delivery of healthcare services. Public sector clinics, homecare companies, and biomedical enterprises should be built to assure the production and distribution of essential medicines and medical technologies as well as healthcare services.

Free from the structural constraints of shareholder primacy and profit maximization, these enterprises will be able to prioritize preventative and curative technologies, fill gaps in existing treatments, and provide products at or below cost where necessary to meet public health needs.

Moreover, they can return revenue to public balance sheets, reduce inefficiencies, and create surge capacity for emergencies. Having a robust public sector infrastructure for the development, manufacture, and distribution of essential goods like medicines, personal protective equipment, and other medical instruments breaks the corporate monopoly over our supply of medical goods, reducing regulatory capture and increasing public power to demand equitable and universal access to critical health goods and services.

Health as a public good offers positive externalities for the economy and society. Even if we just follow the logic of narrow economic growth, a dollar investment in health in developing countries is estimated to result in between $2 and $4 in economic returns over time. And those dollars are best spent when communities and nations have the autonomy to prioritize their own needs and invest in long-term institution-building that will serve their communities for years to come.

Countries like Cuba and Vietnam have demonstrated that, even with modest budgets, developing a sovereign healthcare system that prioritizes primary and preventative care together with robust public health infrastructure can deliver first-rate population health outcomes. [Investing in public healthcare systems has been shown to contribute to better outcomes] than investing in privatized healthcare systems. Freeing the healthcare sector from market imperatives would allow for the recentering of primary and preventative care, planning for equitable access, and robust community health outreach--not traditionally the profit-making parts of healthcare delivery. Additionally, targeted workforce development programs can be created to meet community needs while providing stable, public sector jobs that are themselves an upstream investment in community health.

Reclaiming autonomy of the public sector by sovereign nations requires a shift from the current donor-driven vertical disease control programs most funded in prioritizing the needs of the community. Vertical interventions to eradicate single diseases are often costly and have been imposed on low and middle-income countries at the expense of horizontal enhancements of public health infrastructure that would serve whole populations over the long term and make local health systems more resilient. They also contribute to internal brain drain with skilled people leaving the public sector to work for higher pay in international and nongovernmental organizations.

"The COVID-19 pandemic has opened a window of opportunity to revisit and reevaluate the many myths that held up a broken system of global health. And in doing so, it has offered us the chance to deliver a truly global public health system: equitable, inclusive and people-centered."

Reversal of structural adjustment conditions and untying loans, donor grants and external funding from conditionalities is essential in reclaiming sovereignty in the national public health decision space. Complete restructuring of the global health governance mechanisms to ensure democratic representation in decision-making by every participating country, whether they are net donors or net recipients, is vital. Global health governance mechanisms must have measures in place to ensure that external influence exerted over countries is subordinate to national sovereignty, and that the activities of global health organizations without a democratic mandate are overseen and their impact held to account by national governments.

Representation of the most marginalized and communities most impacted by colonialism and structural adjustment on governance of global health and financial institutions is important for their priorities and perspectives to be included on the agenda and in development priorities. In addition, more community empowerment, participation, and co-planning in the process of deprivatization of healthcare services can aid in the democratization of healthcare and provide increased opportunities for transparency, citizen accountability, and oversight.

Hand-in-hand with the reclaiming of the healthcare sector for the public good should be the reclamation of essential services like water and power. Investments in public power and water--coupled with divestments from fossil fuels--would build both climate resilience and more equitable access to the basic infrastructure of public health. Amongst the greatest challenges to public health in many countries around the world are still infectious diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, and lower respiratory infections, all of which correlate highly to social determinants like access to clean water and good living conditions, air quality, and sanitation. Any strategy to reclaim public health for the public good must center social determinants and seek to increase public power across sectors of the economy responsible for the basic conditions of human life and the stability of our environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic has opened a window of opportunity to revisit and reevaluate the many myths that held up a broken system of global health. And in doing so, it has offered us the chance to deliver a truly global public health system: equitable, inclusive and people-centered.

A withering critique of capitalism is not enough. It is time to reimagine a world where human life and environmental sustainability are the first priority, and where that universal right to health is the basis for all public policy.

A system premised on this universal right--and powered by global solidarity--is not only possible. For our species to survive, it is necessary.

For decades, we have been sold a myth of private health. It is a myth that our health is largely a product of individual choices and personal responsibilities. It is a myth that our healthcare is a service that private corporations can provide, and for which we must pay to survive.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has blown up this myth.

Our personal health cannot be separated from the health of our neighbors or our planet. Nor can it be separated from the structural factors and policy decisions that have determined our health outcomes long before we are born.

The right to health, in the context of these interconnections, is a universal right. Your life is worth no more and no less than that of your next-door neighbor because the fates of the two are so intimately entwined.

"Any strategy to reclaim public health for the public good must center social determinants and seek to increase public power across sectors of the economy responsible for the basic conditions of human life and the stability of our environment."

Today, the universal right to health is not held back by scarcity of resources or a lack of technology. On the contrary, the wealth of this world--invested well--could end the pandemic before the year's end.

Instead, we are held back by another myth: that there exists a trade-off between public health and the health of the economy. The assumption of this trade-off dictates that all public policy is subordinate to the great god of economic growth--even if it costs us our lives. The concept of private health grows out of this second myth, which makes a commodity of our bodies, and a market for essential healthcare services.

Indeed, public health systems around the world are structured carefully to serve a profit motive. Unsurprisingly, their outcomes are inequitable and insufficient, leaving poor and marginalized communities with no recourse to private health provision.

Drawing on the evidence of health impacts of the coronavirus pandemic and the impact of policy responses, the racial, gender and class dimension in the impact of the virus is undeniable. The raw reality of systemic fragility of both public health and economic systems in the North in dealing with the social crisis has also been brought to the fore. Those countries that have been successful--such as Vietnam, Cuba and New Zealand--viewed public health as economic wealth.

Once again, we return to the basic premise. Health, in all its dimensions, is a public good.

How can we deliver a world that reflects this simple premise?

The first step is decolonization. Countries in the Global South cannot deliver on the promise of public health when they are curtailed by neocolonial conditionalities that come along with philanthropic funding and multilateral lending. This top-down approach strips countries of their sovereignty over how to fund health services, privatizes health infrastructure and cripples social policy provisions.

Most of these countries assured universal health services as a matter of course in the 1960s and 1970s. Then came structural adjustment. The imposition of the Washington Consensus in the course of the 1980s and 1990s led to a radical reframing of the health sector as a profitable site of privatization and deregulation. The introduction of user fees and prioritization of imported, high tech-fixes forced millions of poor people to the margins, as "private health" became the norm. Provision in the form of "minimum packages" took priority over comprehensive primary and community health.

Public health, then, requires public ownership--a form of ownership that can deliver transparency and foster citizen participation in the delivery of healthcare services. Public sector clinics, homecare companies, and biomedical enterprises should be built to assure the production and distribution of essential medicines and medical technologies as well as healthcare services.

Free from the structural constraints of shareholder primacy and profit maximization, these enterprises will be able to prioritize preventative and curative technologies, fill gaps in existing treatments, and provide products at or below cost where necessary to meet public health needs.

Moreover, they can return revenue to public balance sheets, reduce inefficiencies, and create surge capacity for emergencies. Having a robust public sector infrastructure for the development, manufacture, and distribution of essential goods like medicines, personal protective equipment, and other medical instruments breaks the corporate monopoly over our supply of medical goods, reducing regulatory capture and increasing public power to demand equitable and universal access to critical health goods and services.

Health as a public good offers positive externalities for the economy and society. Even if we just follow the logic of narrow economic growth, a dollar investment in health in developing countries is estimated to result in between $2 and $4 in economic returns over time. And those dollars are best spent when communities and nations have the autonomy to prioritize their own needs and invest in long-term institution-building that will serve their communities for years to come.

Countries like Cuba and Vietnam have demonstrated that, even with modest budgets, developing a sovereign healthcare system that prioritizes primary and preventative care together with robust public health infrastructure can deliver first-rate population health outcomes. [Investing in public healthcare systems has been shown to contribute to better outcomes] than investing in privatized healthcare systems. Freeing the healthcare sector from market imperatives would allow for the recentering of primary and preventative care, planning for equitable access, and robust community health outreach--not traditionally the profit-making parts of healthcare delivery. Additionally, targeted workforce development programs can be created to meet community needs while providing stable, public sector jobs that are themselves an upstream investment in community health.

Reclaiming autonomy of the public sector by sovereign nations requires a shift from the current donor-driven vertical disease control programs most funded in prioritizing the needs of the community. Vertical interventions to eradicate single diseases are often costly and have been imposed on low and middle-income countries at the expense of horizontal enhancements of public health infrastructure that would serve whole populations over the long term and make local health systems more resilient. They also contribute to internal brain drain with skilled people leaving the public sector to work for higher pay in international and nongovernmental organizations.

"The COVID-19 pandemic has opened a window of opportunity to revisit and reevaluate the many myths that held up a broken system of global health. And in doing so, it has offered us the chance to deliver a truly global public health system: equitable, inclusive and people-centered."

Reversal of structural adjustment conditions and untying loans, donor grants and external funding from conditionalities is essential in reclaiming sovereignty in the national public health decision space. Complete restructuring of the global health governance mechanisms to ensure democratic representation in decision-making by every participating country, whether they are net donors or net recipients, is vital. Global health governance mechanisms must have measures in place to ensure that external influence exerted over countries is subordinate to national sovereignty, and that the activities of global health organizations without a democratic mandate are overseen and their impact held to account by national governments.

Representation of the most marginalized and communities most impacted by colonialism and structural adjustment on governance of global health and financial institutions is important for their priorities and perspectives to be included on the agenda and in development priorities. In addition, more community empowerment, participation, and co-planning in the process of deprivatization of healthcare services can aid in the democratization of healthcare and provide increased opportunities for transparency, citizen accountability, and oversight.

Hand-in-hand with the reclaiming of the healthcare sector for the public good should be the reclamation of essential services like water and power. Investments in public power and water--coupled with divestments from fossil fuels--would build both climate resilience and more equitable access to the basic infrastructure of public health. Amongst the greatest challenges to public health in many countries around the world are still infectious diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, and lower respiratory infections, all of which correlate highly to social determinants like access to clean water and good living conditions, air quality, and sanitation. Any strategy to reclaim public health for the public good must center social determinants and seek to increase public power across sectors of the economy responsible for the basic conditions of human life and the stability of our environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic has opened a window of opportunity to revisit and reevaluate the many myths that held up a broken system of global health. And in doing so, it has offered us the chance to deliver a truly global public health system: equitable, inclusive and people-centered.

A withering critique of capitalism is not enough. It is time to reimagine a world where human life and environmental sustainability are the first priority, and where that universal right to health is the basis for all public policy.

A system premised on this universal right--and powered by global solidarity--is not only possible. For our species to survive, it is necessary.

"Thank you to the hundreds of thousands of Americans across the country who are standing up and speaking out for our voting rights, fundamental freedoms, and essential services like Social Security and Medicare."

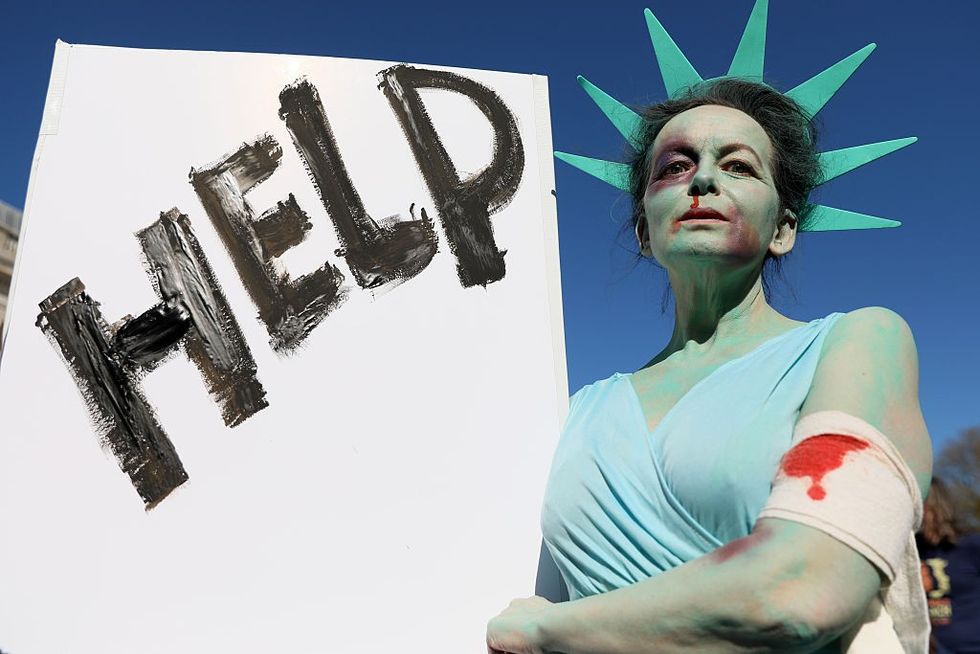

In communities large and small across the United States on Saturday, hundreds of thousands of people collectively took to the streets to make their opposition to President Donald Trump heard.

The people who took part in the organized protests ranged from very young children to the elderly and their message was scrawled on signs of all sizes and colors—many of them angry, some of them funny, but all in line with the "Hands Off" message that brought them together.

"Thank you to the hundreds of thousands of Americans across the country who are standing up and speaking out for our voting rights, fundamental freedoms, and essential services like Social Security and Medicare," said the group Stand Up America as word of the turnout poured in from across the country.

A relatively small, but representative sample of photographs from various demonstrations that took place follows.

Demonstrators gather on Boston Common, cheering and chanting slogans, during the nationwide "Hands Off!" protest against US President Donald Trump and his advisor, Tesla CEO Elon Musk, in Boston, Massachusetts on April 5, 2025. (Photo by Joseph Prezioso / AFP)

"Everyone involved in this crime against humanity, and everyone who covered it up, would face prosecution in a world that had any shred of dignity left."

A video presented to officials at the United Nations on Friday and first made public Saturday by the New York Times provides more evidence that the recent massacre of Palestinian medics in Gaza did not happen the way Israeli government claimed—the latest in a long line of deception when it comes to violence against civilians that have led to repeated accusations of war crimes.

The video, according to the Palestine Red Crescent Society (PRCS), was found on the phone of a paramedic found in a mass grave with a bullet in his head after being killed, along with seven other medics, by Israeli forces on March 23. The eight medics, buried in the shallow grave with the bodies riddled with bullets, were: Mustafa Khafaja, Ezz El-Din Shaat, Saleh Muammar, Refaat Radwan, Muhammad Bahloul, Ashraf Abu Libda, Muhammad Al-Hila, and Raed Al-Sharif. The video reportedly belonged to Radwan. A ninth medic, identified as Asaad Al-Nasasra, who was at the scene of the massacre, which took place near the southern city of Rafah, is still missing.

The PRCS said it presented the video—which refutes the explanation of the killings offered by Israeli officials—to members of the UN Security Council on Friday.

"They were killed in their uniforms. Driving their clearly marked vehicles. Wearing their gloves. On their way to save lives," Jonathan Whittall, head of the UN's humanitarian affairs office in Palestine, said last week after the bodies were discovered. Some of the victims, according to Gaza officials, were found with handcuffs still on them and appeared to have been shot in the head, execution-style.

The Israeli military initially said its soldiers "did not randomly attack" any ambulances, but rather claimed they fired on "terrorists" who approached them in "suspicious vehicles." Lt. Col. Nadav Shoshani, an IDF spokesperson, said the vehicles that the soldiers opened fire on were driving with their lights off and did not have clearance to be in the area. The video evidence directly contradicts the IDF's version of events.

As the Times reports:

The Times obtained the video from a senior diplomat at the United Nations who asked not to be identified to be able to share sensitive information.

The Times verified the location and timing of the video, which was taken in the southern city of Rafah early on March 23. Filmed from what appears to be the front interior of a moving vehicle, it shows a convoy of ambulances and a fire truck, clearly marked, with headlights and flashing lights turned on, driving south on a road to the north of Rafah in the early morning. The first rays of sun can be seen, and birds are chirping.

In an interview with Drop Site News published Friday, the only known paramedic to survive the attack, Munther Abed, explained that he and his colleagues "were directly and deliberately shot at" by the IDF. "The car is clearly marked with 'Palestinian Red Crescent Society 101.' The car's number was clear and the crews' uniform was clear, so why were we directly shot at? That is the question."

The video's release sparked fresh outrage and demands for accountability on Saturday.

"The IDF denied access to the site for days; they sent in diggers to cover up the massacre and intentionally lied about it," said podcast producer Hamza M. Syed in reaction to the new revelations. "The entire leadership of the Israeli army is implicated in this unconscionable war crime. And they must be prosecuted."

"Everyone involved in this crime against humanity, and everyone who covered it up, would face prosecution in a world that had any shred of dignity left," said journalist Ryan Grim of DropSite News.

"They're dismantling our country. They're looting our government. And they think we'll just watch."

In communities across the United States and also overseas, coordinated "Hands Off" protests are taking place far and wide Saturday in the largest public rebuke yet to President Donald Trump and top henchman Elon Musk's assault on the workings of the federal government and their program of economic sabotage that is sacrificing the needs of working families to authoritarianism and the greed of right-wing oligarchs.

Indivisible, one of the key organizing groups behind the day's protests, said millions participated in more than 1,300 individual rallies as they demanded "an end to Trump's authoritarian power grab" and condemning all those aiding and abetting it.

"We expected hundreds of thousands. But at virtually every single event, the crowds eclipsed our estimates," the group said in a statement Saturday evening.

"Hands off our healthcare, hands off our civil rights, hands off our schools, our freedoms, and our democracy."

"This is the largest day of protest since Trump retook office," the group added. "And in many small towns and cities, activists are reporting the biggest protests their communities have ever seen as everyday people send a clear, unmistakable message to Trump and Musk: Hands off our healthcare, hands off our civil rights, hands off our schools, our freedoms, and our democracy."

According to the organizers' call to action:

They're dismantling our country. They’re looting our government. And they think we'll just watch.

On Saturday, April 5th, we rise up with one demand: Hands Off!

This is a nationwide mobilization to stop the most brazen power grab in modern history. Trump, Musk, and their billionaire cronies are orchestrating an all-out assault on our government, our economy, and our basic rights—enabled by Congress every step of the way. They want to strip America for parts—shuttering Social Security offices, firing essential workers, eliminating consumer protections, and gutting Medicaid—all to bankroll their billionaire tax scam.

They're handing over our tax dollars, our public services, and our democracy to the ultra-rich. If we don't fight now, there won’t be anything left to save.

The more than 1,300 "Hands Off!" demonstrations—organized by a large coalition of unions, progressive advocacy groups, and pro-democracy watchdogs—first kicked off Saturday in Europe, followed by East Coast communities in the U.S., and continued throughout the day at various times, depending on location. See here for a list of scheduled "Hands Off" events.

"The United States has a president, not a king," said the progressive advocacy group People's Action, one of the group's involved in the actions, in an email to supporters Saturday morning just as protest events kicked off in hundreds of cities and communities. "Donald Trump has, by every measure, been working to make himself a king. He has become unanswerable to the courts, Congress, and the American people."

In its Saturday evening statement, Indivisible said the actions far exceeded their expectations and should be seen as a turning point in the battle to stop Trump and his minions:

The Trump administration has spent its first 75 days in office trying to overwhelm us, to make us feel powerless, so that we will fall in line, accept the ransacking of our government, the raiding of our social safety net, and the dismantling of our democracy.

And too often, the response from our leaders and those in positions to resist has been abject cowardice. Compliance. Obeying in advance.

But not today. Today we've demonstrated a different path forward. We've modeled the courage and action that we want to see from our leaders, and showed all those who've been standing on the sidelines who share our values that they are not alone.

Citing the Republican president's thirst for "power and greed," People's Action earlier explained why organized pressure must be built and sustained against the administration, especially at the conclusion of a week in which the global economy was spun into disarray by Trump's tariff announcement, his attack on the rule of law continued, and the twice-elected president admitted he was "not joking" about the possibility of seeking a third term, which is barred by the constitution.

"He is destroying the economy with tariffs in order to pay for the tax cuts he wants to push through to enrich himself and his billionaire buddies," warned People's Action. "He has ordered the government to round up innocent people off of the streets and put them in detention centers without due process because they dared to speak out using their First Amendment rights. And he is not close to being done—by his own admission, he is planning to run for a third term, which the Constitution does not allow."

Live stream of Hands Off rally in Washington, D.C.:

Below are photo or video dispatches from demonstrations around the world on Saturday. Check back for updates...

United Kingdom

France

Germany

Belgium:

Massachusetts:

Maine:

Washington, D.C.:

New York:

Minnesota:

Michigan:

Ohio:

Colorado:

Pennsylvania:

North Carolina:

The protest organizers warn that what Trump and Musk are up to "is not just corruption" and "not just mismanagement," but something far more sinister.

"This is a hostile takeover," they said, but vowed to fight back. "This is the moment where we say NO. No more looting, no more stealing, no more billionaires raiding our government while working people struggle to survive."