After the pandemic sent state and local budgets into a tailspin, public sector workers across the country were suddenly faced with furloughs, layoffs, and potentially deep concessions. Although federal stimulus through the CARES Act helped avert a budgetary freefall last spring, more than 1.3 million state and local government workers lost their jobs in 2020.

More than 1.3 million state and local government workers lost their jobs in 2020... Potential shortfalls could translate into massive budget cuts--putting the brake on any economic recovery.

Higher education workers and public school staff saw the largest immediate losses, but public workers everywhere felt the budget squeeze and spent months waiting for the other shoe to drop.

State shortfalls over the next two years could be as high as $300 billion, according to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. And cities face a $90 billion gap this year alone, the National League of Cities reported in February.

Because state and local governments must balance their budgets each year, these potential shortfalls could translate into massive budget cuts--putting the brake on any economic recovery and giving employers a green light to push concessions, restructuring, and whatever else was already on their wish list.

Thankfully, lawmakers in Washington aren't waiting to see if the dire predictions pan out. The American Rescue Plan Act, signed into law on March 11, will funnel $195 billion to state governments and the District of Columbia, and an additional $130 billion to cities, counties, Native governments, and U.S. territories. It will also provide $123 billion for public schools and $29 billion for public colleges and universities.

But will it be enough?

Shock and Awe

The aggressive federal aid is certainly welcome news for public workers like bus operator JorDann Crawford, a member of Transit (ATU) Local 1575. She and her co-workers spent last fall fighting layoffs across the 25 regional transit systems serving the Bay Area, after CARES Act funds started drying up.

"If I'm going to lose my job," Crawford said, "I'm going to go down fighting." Together, she and the others in a multi-union coalition got the layoffs postponed until 2021. And in December, after Congress approved $14 billion in new transit funding, the board rescinded the layoffs entirely.

Ian McCullough and his colleagues at the University of Akron weren't so lucky. Their University Professors (AAUP) local was in bargaining when the pandemic hit. The university invoked the union contract's "force majeure" clause, arguing that Covid-19 was so disastrous that it gave administrators the right to bypass seniority in determining layoffs.

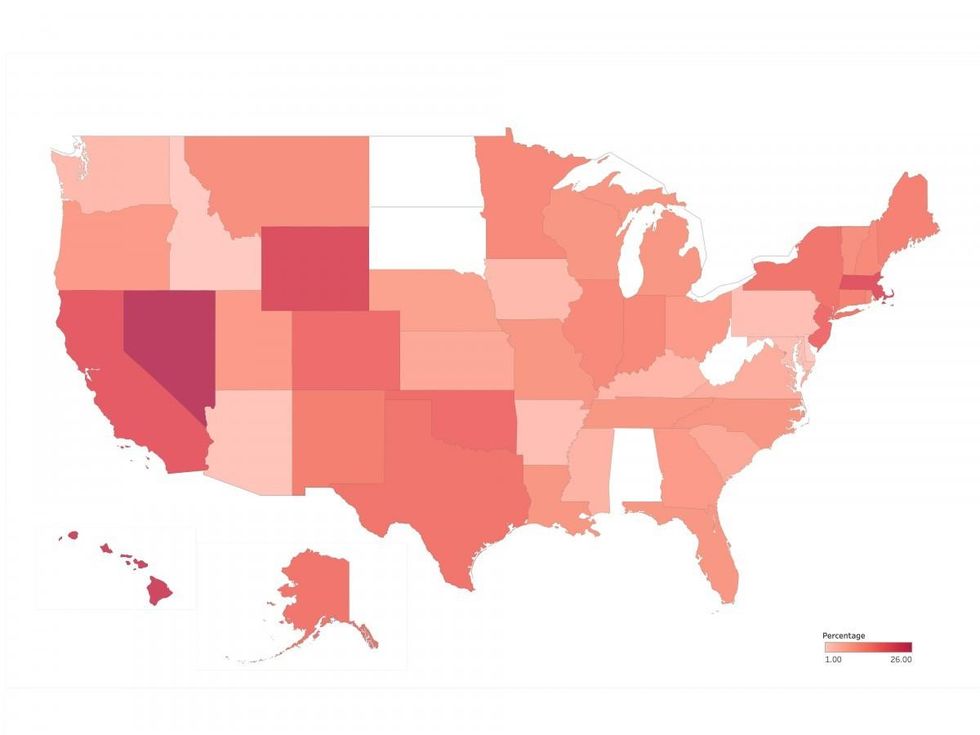

2021 Shortfalls as a Percentage of Pre-Covid Revenue Forecast

In July, the Board of Trustees voted to lay off a "Hit List" of 178 workers, including 96 of the 518 faculty and librarians in the bargaining unit. McCullough, a Physical Sciences librarian, helped organize a no vote on the university's final offer, which was narrowly rejected. The union filed a class-action grievance against the reductions in force, which affected about 70 workers after early retirements, but lost the arbitration in September.

This shock-and-awe approach to managing pandemic-induced budget shortfalls has been all too common in higher ed--but has also spread to cities like Dayton, Ohio, where lawmakers initially furloughed a quarter of the workforce.

After Ohio began reopening in May, most of Dayton's 480 furloughed workers were brought back. But faced with a big drop in tax revenue, the city offered cash payments for employees to retire or quit, and left 120 workers on furlough. It is now postponing its 2021 class for police and firefighters.

History Repeating Itself?

Even in places where unionized workers have managed to avoid job losses, it's come at a steep price. In New York City, for example, Covid created a $5 billion budget shortfall in this year's budget, and Mayor de Blasio told the municipal unions that they needed to find $1 billion in savings or face 22,000 layoffs, nearly 7% of the city's workforce.

In a flashback to the city's 1970s financial crisis, one by one unions reached a deal with the mayor to save jobs and keep the city solvent. The United Federation of Teachers postponed half of a $450 million retro payment that was due in October in exchange for no layoffs before July 2021. AFSCME District Council 37 agreed to postpone $164 million in contributions to the union's benefit fund for a similar commitment.

Meanwhile, early retirements and unfilled positions are hollowing out the workforce, eroding city services, and increasing the workload of everyone left.

Fortunately, the Biden administration seems determined to avoid the Obama-era mistake of being too timid with its first stimulus package. The American Rescue Plan provides three times more aid to state and local governments than the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act did.

It's a good thing too, because as many public workers remember, the biggest budget cuts from the Great Recession happened in 2010 and 2011, long after Wall Street had come roaring back and federal aid was a distant memory. Some cities, like Dayton, never really recovered from the financial meltdown before the pandemic hit.

Going on Offense

No matter how generous, the current stimulus is a one-time infusion into city and state coffers. That's why union activists around the country are focused on fixing our upside-down tax system and making corporations and the ultra-wealthy pay their fair share.

During the first 11 months of the pandemic, U.S. billionaires saw their wealth increase by 40%--a whopping $1.3 trillion. This has prompted a growing number of union activists to push for aggressive revenue strategies.

During the first 11 months of the pandemic, U.S. billionaires saw their wealth increase by 40%--a whopping $1.3 trillion--according to a report from the Institute for Policy Studies and Americans for Tax Fairness.

This has prompted a growing number of union activists to push for aggressive revenue strategies. Last summer, the New Jersey legislature passed a millionaires tax that could raise up to $450 million a year. The victory came after unions and progressive allies had failed on six previous attempts--which may provide some comfort to California labor activists, who suffered a heartbreaker in November. Prop 15, a ballot initiative that would have closed a corporate tax loophole and raised up to $12 billion for California's schools and services, failed by a slim margin.

Seattle activists were vindicated last July when their city council passed a first-ever tax on Amazon and other big businesses that will bring in more than $200 million each year.

Two years earlier, Amazon had forced the council to rescind a much more modest tax measure. But thanks to a grassroots campaign spearheaded by socialist Councilmember Kshama Sawant and anchored by hundreds of union and community activists, the city will now have money to create affordable housing and green jobs.

Even more ambitious efforts are already in the works. In New York state, a union-community coalition is pushing a package of six bills that would raise $50 billion. And in Connecticut, SEIU 1199 New England is anchoring a coalition pushing to raise $3 billion--targeting the state's lucrative financial services industry along with its 17 billionaires.

Big Dreams in Connecticut

The union, which represents 6,000 state employees in public health agencies, is pressing these demands at the bargaining table, along with the 15-union State Employee Bargaining Agent Coalition, representing 46,000 other state employees.

The revenue campaign is just one piece of a bigger vision. "Unions that do public service work have a responsibility to expand the scope of collective bargaining beyond wages and benefits, to talking about the quality of life," said 1199 New England President Rob Baril.

For the past year 1199 New England has also been working with community allies to develop a series of specific racial justice bargaining demands, including expansion of the state's mobile crisis service--so that mental health workers, not police, are the ones who respond to people suffering mental health crises. And since the state has decided to close a supermax prison, the union is pushing to redirect those funds away from the prison system and into improving re-entry services for the formerly incarcerated.

Public sector workers in Connecticut don't have the right to strike, so the union is gearing up for big civil disobedience actions to draw attention to these issues. It's also setting strike deadlines this spring for its 10,000 members in private sector nursing homes and group homes to further pressure the legislature and Democratic Governor Ned Lamont.

"Our biggest challenge is not dreaming big enough," said Baril. "Let's talk about the world that we deserve and fight like hell to get there, then let the chips fall where they may."