Then-President Donald Trump's call to widen libel laws to make it easier to sue media outlets for defamation was, at the time, seen as one of his many political theatrical stunts, throwing red meat to his voting base (New York Times, 1/10/18). Following his lead, his supporters had long referred to the press as "fake news," sometimes using the Nazi expression lugenpresse, meaning "lying press" (Time, 10/25/16).

Corporate media covered it, but dismissed the threat. The Los Angeles Times (9/8/18) said we shouldn't worry, because "changing our libel laws is easier said than done," and CNBC (1/10/18) reassured that "experts say there is very little Trump could actually change about how libel laws work."

But a dissenting opinion from the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia (Slate, 3/19/21) has breathed new legal life into the prospect of making it easier for political and corporate leaders to use defamation suits to stifle the press. The human rights group Global Witness had been sued by two Liberian officials it had accused of taking bribes from Exxon, but the court threw out the case, citing the landmark Supreme Court decision New York Times v. Sullivan, which held in 1964 that plaintiffs who are public figures must prove "actual malice" to win a libel suit.

Justice Laurence Silberman's dissent, however, is a sight to behold. He pontificates about an out-of-control liberal press and the anti-conservative bias of social media--standard Republican talking points--before ultimately declaring that Sullivan, which he insinuates is Communist-inspired ("a constitutional Brezhnev doctrine"), must be overturned.

It's easy to dismiss as someone using the winter of his judicial perch as the next best thing to a Fox News show, but Silberman is not a nobody. A Reagan appointee and Federalist Society member, Silberman has been accused of taking part of Ronald Reagan's "October Surprise" (Chicago Tribune, 8/18/89), an attempt to interfere in Iranian hostage negotiations to prevent President Jimmy Carter's re-election, and is infamous for overturning the conviction of Oliver North (New York Times, 7/21/90). He reportedly heaped on the attack against Anita Hill. He took up the Confederate Lost Cause last summer when he, as Slatereported, sent an email to colleagues "accusing Sen. Elizabeth Warren of seeking 'the desecration of Confederate graves,'" in response to her call for renaming "military bases that are named after Confederate officers." When a loyal soldato for the judicial right speaks, we should listen.

The idea of revisiting this precedent has been kicking around conservative circles for a while. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, the godfather of modern conservative legal philosophy, told the National Press Club (C-SPAN, 4/17/14; National Press Club, 4/21/14) that "the framers would have been appalled with the notion that they could be libeled with impunity," and that the justices who issued the ruling "were revising the Constitution." Justice Clarence Thomas suggested in 2019 that the decision and subsequent decisions based on it "were policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law," prompting the libertarian Reason (2/19/19) to say "it's true that reconsidering New York Times v. Sullivan could lead to opening up our libel laws," but that it "doesn't follow that it's a bad and wrong thing to do."

Legal scholar Richard Epstein has been critical of the decision since the 1980s, and told the podcast We the People (10/11/18), "The difficulty with the actual malice standard is it traces too much on what the defendants thought," underemphasizing the "harm to the plaintiff's reputation, which in many of these cases can be quite devastating." He added that the actual malice requirement "was a radical departure from all pre-existing cases on the subject, and to my mind a mistake." Epstein told FAIR that the decision lets the press off the hook: "Sullivan lets false statements go unredressed no matter how much they do," he said, adding that a media outlet's "reputation should take a hit when they mislead their readers."

The actual malice standard is meant to protect speech, and especially speech from the common person used against those with power. Without this protection, political and business leaders, with their bottomless legal war chests, can simply use the threat of litigation to throw a chilling shroud over journalists and political activists. On the 50th anniversary of the decision, a New York Times editorial (3/8/14) called the decision "the clearest and most forceful defense of press freedom in American history," because it "rejected virtually any attempt to squelch criticism of public officials--even if false -- as antithetical to 'the central meaning of the First Amendment.'"

Chad Bowman, the attorney for Global Witness in this DC circuit case, told FAIR that "New York Times v. Sullivan provides important 'breathing space' for lively discussion and debate on issues of public concern," and thus "is essential to a democracy." He added that we should

remember that the speech-protective legal standard is not limited to reporters at certain news organizations or members of a particular political party, but applies to all speakers.

That last part is key: Silberman was attacking the perceived partisanship of the press, but free speech protections are meant to apply across the political spectrum; if they're denied to one faction, they're effectively denied to everyone. And the First Amendment isn't just for journalists. Widening the application of defamation for powerful public figures will make it harder for the corporate press to cover state and corporate power, but will make it far more daunting for average people, who lack legal departments and libel insurance, to take part in public debate.

More than that, perceived partisan imbalance in the media isn't a reason to restrict free speech rights for everyone. Silberman thinks the press is too liberal. Readers of FAIR.org would more likely say the U.S. press is too deferential to corporate and government power, but the answer to fixing that isn't more legal restrictions on those media outlets, but the creation of more independent media.

And Silberman brings up the idea that social media networks have a bias in terms of controlling what kind of media can be taken down or approved. People of all political stripes do see a problem with the power these few ubiquitous companies have (FAIR.org, 1/15/21), but the answer, again, isn't to have the government dictate how these private entities regulate speech. If you want a social media network that doesn't reflect private interests, then you need one that is owned by the public, like the U.S. Postal Service.

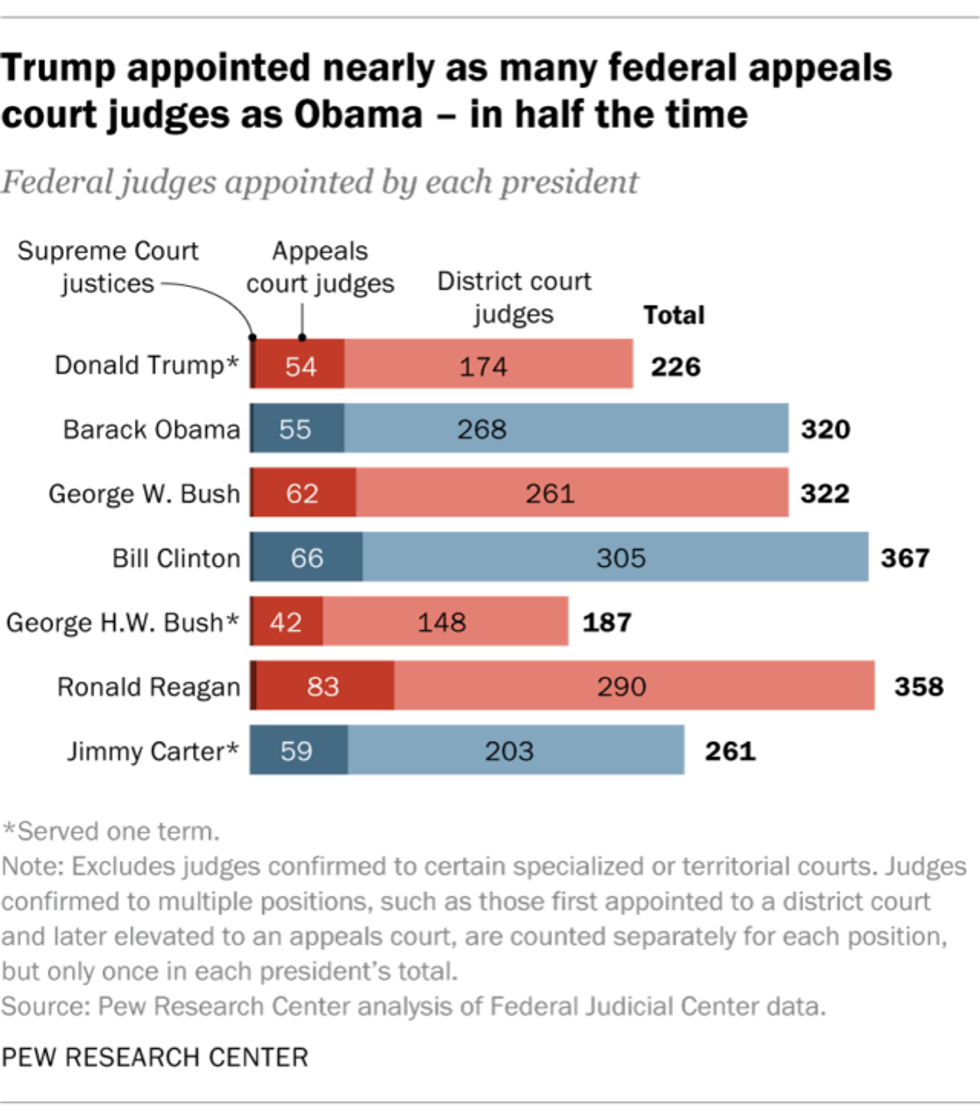

With key right-wing jurists now on record calling for the overturning of this landmark ruling for freedom of the press, that the courts should undo this cornerstone of free speech, it's worth considering the right's grip on the federal bench. Pew Research (1/13/21) notes that "Trump appointed 54 federal appellate judges in four years, one short of the 55 Obama appointed in twice as much time," and that "more than a quarter of currently active federal judges are now Trump appointees." It's not a stretch to assume that this army of judicial ideologues, put in power by an administration whose goal was to use the federal judiciary to curb democratic liberalism, are familiar with Epstein, Silberman, Thomas and Scalia's arguments regarding New York Times v. Sullivan.

Obviously, First Amendment advocates need to be ready to defend against litigation aimed at empowering corporate and government honchos who want to quash their critics in the press. But there needs to be offensive action, too, and there's perhaps a way to unite the left-wing FAIR.org reader and the right-wing Silberman apprentice.

We might agree, for different reasons, that mass media fall short in serving its public purpose, and that social media networks are too powerful. But we could, theoretically, agree that the solution is the encouragement of more speech, through policies that allow for more community radio projects, funding for more local media and, in the case of social media, breaking up their monopoly status.

The struggle to preserve free speech cannot just be a defense of a precedent from the Civil Rights Era. There must be a 21st century manifesto for more media and more speech.