Protesters picket outside Johnson & Johnson offices in Cape Town, South Africa during the Global Day Of Action For A People's Vaccine on March 11, 2021. (Photo: Brenton Geach/Gallo Images via Getty Images)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Protesters picket outside Johnson & Johnson offices in Cape Town, South Africa during the Global Day Of Action For A People's Vaccine on March 11, 2021. (Photo: Brenton Geach/Gallo Images via Getty Images)

In the race between infection and injection, injection has lost.

Public health experts estimate that approximately 70% of the world's 7.9 billion people must be fully vaccinated to end the COVID-19 pandemic. As of June 21, 2021, 10.04% of the global population had been fully vaccinated, nearly all of them in rich countries.

Only 0.9% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose.

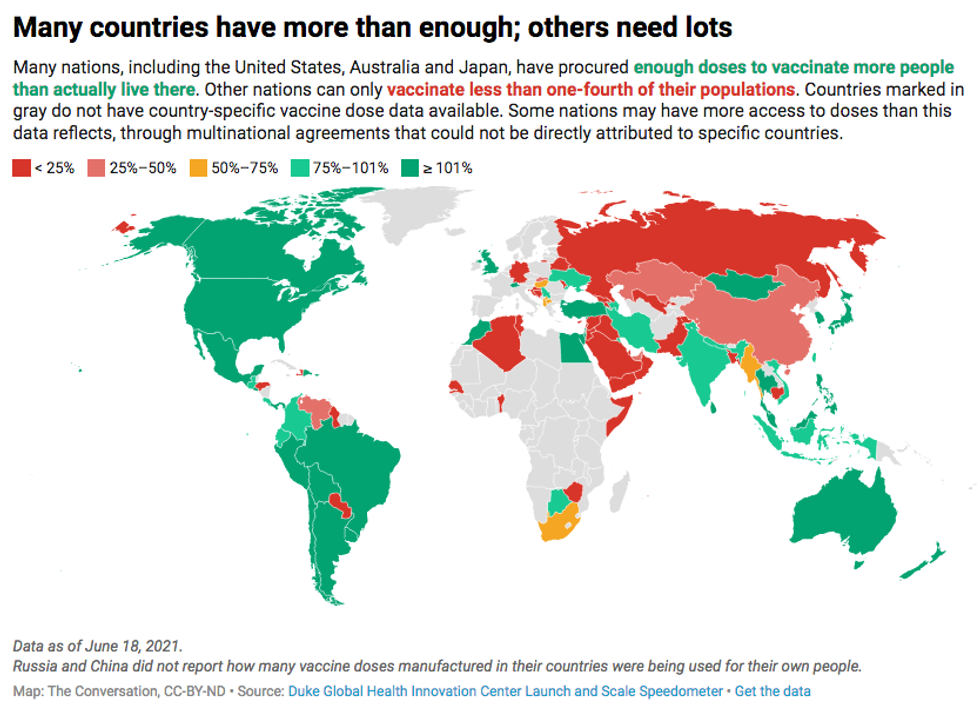

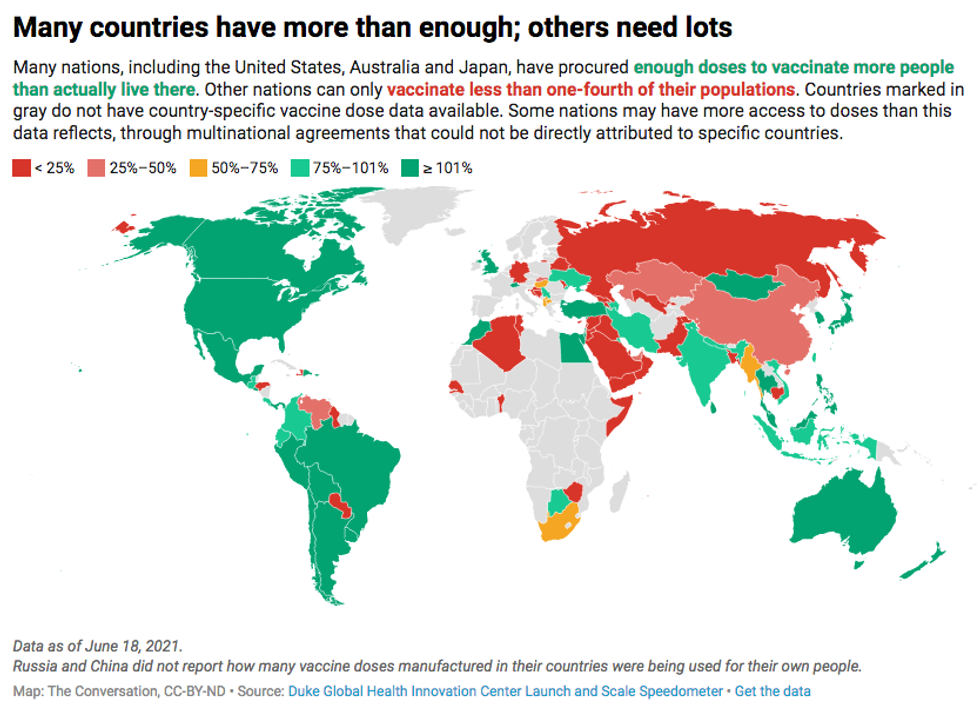

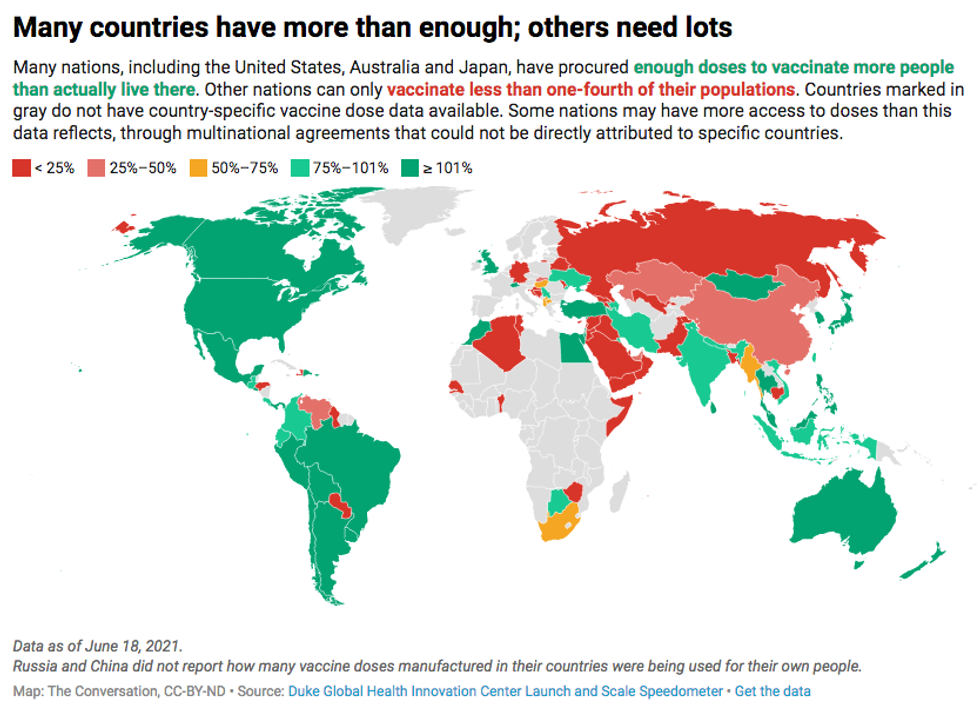

I am a scholar of global health who specializes in health care inequities. Using a data set on vaccine distribution compiled by the Global Health Innovation Center's Launch and Scale Speedometer at Duke University in the United States, I analyzed what the global vaccine access gap means for the world.

Supply is not the main reason some countries are able to vaccinate their populations while others experience severe disease outbreaks--distribution is.

Many rich countries pursued a strategy of overbuying COVID-19 vaccine doses in advance. My analyses demonstrate that the U.S., for example, has procured 1.2 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses, or 3.7 doses per person. Canada has ordered 381 million doses; every Canadian could be vaccinated five times over with the two doses needed.

Overall, countries representing just one-seventh of the world's population had reserved more than half of all vaccines available by June 2021. That has made it very difficult for the remaining countries to procure doses, either directly or through COVAX, the global initiative created to enable low- to middle-income countries equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines.

Benin, for example, has obtained about 203,000 doses of China's Sinovac vaccine--enough to fully vaccinate 1% of its population. Honduras, relying mainly on AstraZeneca, has procured approximately 1.4 million doses. That will fully vaccinate 7% of its population. In these "vaccine deserts," even front-line health workers aren't yet inoculated.

Haiti has received about 461,500 COVID-19 vaccine doses by donations and is grappling with a serious outbreak.

Even COVAX's goal--for lower-income countries to "receive enough doses to vaccinate up to 20% of their population"--would not get COVID-19 transmission under control in those places.

Last year, researchers at Northeastern University modeled two vaccine rollout strategies. Their numerical simulations found that 61% of deaths worldwide would have been averted if countries cooperated to implement an equitable global vaccine distribution plan, compared with only 33% if high-income countries got the vaccines first.

Put briefly, when countries cooperate, COVID-19 deaths drop by approximately in half.

Vaccine access is inequitable within countries, too--especially in countries where severe inequality already exists.

In Latin America, for example, a disproportionate number of the tiny minority of people who've been vaccinated are elites: political leaders, business tycoons and those with the means to travel abroad to get vaccinated. This entrenches wider health and social inequities.

The result, for now, is two separate and unequal societies in which only the wealthy are protected from a devastating disease that continues to ravage those who are not able to access the vaccine.

This is a familiar story from the HIV era.

In the 1990s, the development of effective antiretroviral drugs for HIV/AIDS saved millions of lives in high-income countries. However, about 90% of the global poor who were living with HIV had no access to these lifesaving drugs.

Concerned about undercutting their markets in high-income countries, the pharmaceutical companies that produced antiretrovirals, such as Burroughs Wellcome, adopted internationally consistent prices. Azidothymidine, the first drug to fight HIV, cost about US$8,000 a year - over $19,000 in today's dollars.

That effectively placed effective HIV/AIDS drugs out of reach for people in poor nations--including countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the epidemic's epicenter. By the year 2000, 22 million people in sub-Saharan Africa were living with HIV, and AIDS was the region's leading cause of death.

The crisis over inequitable access to AIDS treatment began dominating international news headlines, and the rich world's obligation to respond became too great to ignore.

"History will surely judge us harshly if we do not respond with all the energy and resources that we can bring to bear in the fight against HIV/AIDS," said South African President Nelson Mandela in 2004.

A 9-year-old girl in Johannesburg, South Africa, prays before taking her twice-daily HIV medications in 2002. (Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images)

Pharmaceutical companies began donating antiretrovirals to countries in need and allowing local businesses to manufacture generic versions, providing bulk, low-cost access for highly affected poor countries. New global institutions like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria were created to finance health programs in poor countries.

Pressured by grassroots activism, the United States and other high-income countries also spent billions of dollars to research, develop and distribute affordable HIV treatments worldwide.

It took over a decade after the development of antiretrovirals, and millions of unnecessary deaths, for rich countries to make those lifesaving medicines universally available.

Fifteen months into the current pandemic, wealthy, highly vaccinated countries are starting to assume some responsibility for boosting global vaccination rates.

Leaders of the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, European Union and Japan recently pledged to donate a total of 1 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses to poorer countries.

It is not yet clear how their plan to "vaccinate the world" by the end of 2022 will be implemented and whether recipient countries will receive enough doses to fully vaccinate enough people to control viral spread. And the late 2022 goal will not save people in the developing world who are dying of COVID-19 in record numbers now, from Brazil to India.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic shows that ending the coronavirus pandemic will require, first, prioritizing access to COVID-19 vaccines on the global political agenda. Then wealthy nations will need to work with other countries to build their vaccine manufacturing infrastructure, scaling up production worldwide.

Finally, poorer countries need more money to fund their public health systems and purchase vaccines. Wealthy countries and groups like the G-7 can provide that funding.

These actions benefit rich countries, too. As long as the world has unvaccinated populations, COVID-19 will continue to spread and mutate. Additional variants will emerge.

As a May 2021 UNICEF statement put it: "In our interdependent world no one is safe until everyone is safe."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

In the race between infection and injection, injection has lost.

Public health experts estimate that approximately 70% of the world's 7.9 billion people must be fully vaccinated to end the COVID-19 pandemic. As of June 21, 2021, 10.04% of the global population had been fully vaccinated, nearly all of them in rich countries.

Only 0.9% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose.

I am a scholar of global health who specializes in health care inequities. Using a data set on vaccine distribution compiled by the Global Health Innovation Center's Launch and Scale Speedometer at Duke University in the United States, I analyzed what the global vaccine access gap means for the world.

Supply is not the main reason some countries are able to vaccinate their populations while others experience severe disease outbreaks--distribution is.

Many rich countries pursued a strategy of overbuying COVID-19 vaccine doses in advance. My analyses demonstrate that the U.S., for example, has procured 1.2 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses, or 3.7 doses per person. Canada has ordered 381 million doses; every Canadian could be vaccinated five times over with the two doses needed.

Overall, countries representing just one-seventh of the world's population had reserved more than half of all vaccines available by June 2021. That has made it very difficult for the remaining countries to procure doses, either directly or through COVAX, the global initiative created to enable low- to middle-income countries equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines.

Benin, for example, has obtained about 203,000 doses of China's Sinovac vaccine--enough to fully vaccinate 1% of its population. Honduras, relying mainly on AstraZeneca, has procured approximately 1.4 million doses. That will fully vaccinate 7% of its population. In these "vaccine deserts," even front-line health workers aren't yet inoculated.

Haiti has received about 461,500 COVID-19 vaccine doses by donations and is grappling with a serious outbreak.

Even COVAX's goal--for lower-income countries to "receive enough doses to vaccinate up to 20% of their population"--would not get COVID-19 transmission under control in those places.

Last year, researchers at Northeastern University modeled two vaccine rollout strategies. Their numerical simulations found that 61% of deaths worldwide would have been averted if countries cooperated to implement an equitable global vaccine distribution plan, compared with only 33% if high-income countries got the vaccines first.

Put briefly, when countries cooperate, COVID-19 deaths drop by approximately in half.

Vaccine access is inequitable within countries, too--especially in countries where severe inequality already exists.

In Latin America, for example, a disproportionate number of the tiny minority of people who've been vaccinated are elites: political leaders, business tycoons and those with the means to travel abroad to get vaccinated. This entrenches wider health and social inequities.

The result, for now, is two separate and unequal societies in which only the wealthy are protected from a devastating disease that continues to ravage those who are not able to access the vaccine.

This is a familiar story from the HIV era.

In the 1990s, the development of effective antiretroviral drugs for HIV/AIDS saved millions of lives in high-income countries. However, about 90% of the global poor who were living with HIV had no access to these lifesaving drugs.

Concerned about undercutting their markets in high-income countries, the pharmaceutical companies that produced antiretrovirals, such as Burroughs Wellcome, adopted internationally consistent prices. Azidothymidine, the first drug to fight HIV, cost about US$8,000 a year - over $19,000 in today's dollars.

That effectively placed effective HIV/AIDS drugs out of reach for people in poor nations--including countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the epidemic's epicenter. By the year 2000, 22 million people in sub-Saharan Africa were living with HIV, and AIDS was the region's leading cause of death.

The crisis over inequitable access to AIDS treatment began dominating international news headlines, and the rich world's obligation to respond became too great to ignore.

"History will surely judge us harshly if we do not respond with all the energy and resources that we can bring to bear in the fight against HIV/AIDS," said South African President Nelson Mandela in 2004.

A 9-year-old girl in Johannesburg, South Africa, prays before taking her twice-daily HIV medications in 2002. (Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images)

Pharmaceutical companies began donating antiretrovirals to countries in need and allowing local businesses to manufacture generic versions, providing bulk, low-cost access for highly affected poor countries. New global institutions like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria were created to finance health programs in poor countries.

Pressured by grassroots activism, the United States and other high-income countries also spent billions of dollars to research, develop and distribute affordable HIV treatments worldwide.

It took over a decade after the development of antiretrovirals, and millions of unnecessary deaths, for rich countries to make those lifesaving medicines universally available.

Fifteen months into the current pandemic, wealthy, highly vaccinated countries are starting to assume some responsibility for boosting global vaccination rates.

Leaders of the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, European Union and Japan recently pledged to donate a total of 1 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses to poorer countries.

It is not yet clear how their plan to "vaccinate the world" by the end of 2022 will be implemented and whether recipient countries will receive enough doses to fully vaccinate enough people to control viral spread. And the late 2022 goal will not save people in the developing world who are dying of COVID-19 in record numbers now, from Brazil to India.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic shows that ending the coronavirus pandemic will require, first, prioritizing access to COVID-19 vaccines on the global political agenda. Then wealthy nations will need to work with other countries to build their vaccine manufacturing infrastructure, scaling up production worldwide.

Finally, poorer countries need more money to fund their public health systems and purchase vaccines. Wealthy countries and groups like the G-7 can provide that funding.

These actions benefit rich countries, too. As long as the world has unvaccinated populations, COVID-19 will continue to spread and mutate. Additional variants will emerge.

As a May 2021 UNICEF statement put it: "In our interdependent world no one is safe until everyone is safe."

In the race between infection and injection, injection has lost.

Public health experts estimate that approximately 70% of the world's 7.9 billion people must be fully vaccinated to end the COVID-19 pandemic. As of June 21, 2021, 10.04% of the global population had been fully vaccinated, nearly all of them in rich countries.

Only 0.9% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose.

I am a scholar of global health who specializes in health care inequities. Using a data set on vaccine distribution compiled by the Global Health Innovation Center's Launch and Scale Speedometer at Duke University in the United States, I analyzed what the global vaccine access gap means for the world.

Supply is not the main reason some countries are able to vaccinate their populations while others experience severe disease outbreaks--distribution is.

Many rich countries pursued a strategy of overbuying COVID-19 vaccine doses in advance. My analyses demonstrate that the U.S., for example, has procured 1.2 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses, or 3.7 doses per person. Canada has ordered 381 million doses; every Canadian could be vaccinated five times over with the two doses needed.

Overall, countries representing just one-seventh of the world's population had reserved more than half of all vaccines available by June 2021. That has made it very difficult for the remaining countries to procure doses, either directly or through COVAX, the global initiative created to enable low- to middle-income countries equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines.

Benin, for example, has obtained about 203,000 doses of China's Sinovac vaccine--enough to fully vaccinate 1% of its population. Honduras, relying mainly on AstraZeneca, has procured approximately 1.4 million doses. That will fully vaccinate 7% of its population. In these "vaccine deserts," even front-line health workers aren't yet inoculated.

Haiti has received about 461,500 COVID-19 vaccine doses by donations and is grappling with a serious outbreak.

Even COVAX's goal--for lower-income countries to "receive enough doses to vaccinate up to 20% of their population"--would not get COVID-19 transmission under control in those places.

Last year, researchers at Northeastern University modeled two vaccine rollout strategies. Their numerical simulations found that 61% of deaths worldwide would have been averted if countries cooperated to implement an equitable global vaccine distribution plan, compared with only 33% if high-income countries got the vaccines first.

Put briefly, when countries cooperate, COVID-19 deaths drop by approximately in half.

Vaccine access is inequitable within countries, too--especially in countries where severe inequality already exists.

In Latin America, for example, a disproportionate number of the tiny minority of people who've been vaccinated are elites: political leaders, business tycoons and those with the means to travel abroad to get vaccinated. This entrenches wider health and social inequities.

The result, for now, is two separate and unequal societies in which only the wealthy are protected from a devastating disease that continues to ravage those who are not able to access the vaccine.

This is a familiar story from the HIV era.

In the 1990s, the development of effective antiretroviral drugs for HIV/AIDS saved millions of lives in high-income countries. However, about 90% of the global poor who were living with HIV had no access to these lifesaving drugs.

Concerned about undercutting their markets in high-income countries, the pharmaceutical companies that produced antiretrovirals, such as Burroughs Wellcome, adopted internationally consistent prices. Azidothymidine, the first drug to fight HIV, cost about US$8,000 a year - over $19,000 in today's dollars.

That effectively placed effective HIV/AIDS drugs out of reach for people in poor nations--including countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the epidemic's epicenter. By the year 2000, 22 million people in sub-Saharan Africa were living with HIV, and AIDS was the region's leading cause of death.

The crisis over inequitable access to AIDS treatment began dominating international news headlines, and the rich world's obligation to respond became too great to ignore.

"History will surely judge us harshly if we do not respond with all the energy and resources that we can bring to bear in the fight against HIV/AIDS," said South African President Nelson Mandela in 2004.

A 9-year-old girl in Johannesburg, South Africa, prays before taking her twice-daily HIV medications in 2002. (Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images)

Pharmaceutical companies began donating antiretrovirals to countries in need and allowing local businesses to manufacture generic versions, providing bulk, low-cost access for highly affected poor countries. New global institutions like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria were created to finance health programs in poor countries.

Pressured by grassroots activism, the United States and other high-income countries also spent billions of dollars to research, develop and distribute affordable HIV treatments worldwide.

It took over a decade after the development of antiretrovirals, and millions of unnecessary deaths, for rich countries to make those lifesaving medicines universally available.

Fifteen months into the current pandemic, wealthy, highly vaccinated countries are starting to assume some responsibility for boosting global vaccination rates.

Leaders of the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, European Union and Japan recently pledged to donate a total of 1 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses to poorer countries.

It is not yet clear how their plan to "vaccinate the world" by the end of 2022 will be implemented and whether recipient countries will receive enough doses to fully vaccinate enough people to control viral spread. And the late 2022 goal will not save people in the developing world who are dying of COVID-19 in record numbers now, from Brazil to India.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic shows that ending the coronavirus pandemic will require, first, prioritizing access to COVID-19 vaccines on the global political agenda. Then wealthy nations will need to work with other countries to build their vaccine manufacturing infrastructure, scaling up production worldwide.

Finally, poorer countries need more money to fund their public health systems and purchase vaccines. Wealthy countries and groups like the G-7 can provide that funding.

These actions benefit rich countries, too. As long as the world has unvaccinated populations, COVID-19 will continue to spread and mutate. Additional variants will emerge.

As a May 2021 UNICEF statement put it: "In our interdependent world no one is safe until everyone is safe."