SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

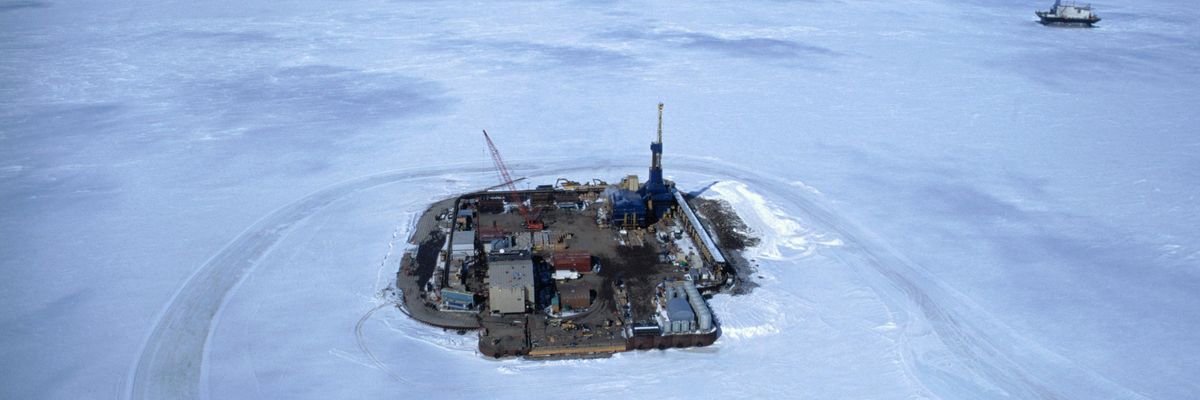

BP North Star oil station, North Slope, Alaska, USA. (Photo: Damian Gillie/Construction Photography/Avalon/Getty Images)

It just takes common sense to see that the climate change math of the Biden administration is not adding up: You cannot approve massive oil drilling projects if you want to swiftly reach net-zero emissions.

That is exactly what the administration did when it sided with ConocoPhillips in the company's bid to drill for more than a half billion barrels of oil in the National Petroleum Reserve (NPR) in the Alaskan Arctic, erecting infrastructure that will be in operation for 30 years or more. After spending $6 million in federal funds and generating more than 3,600 pages of environmental analysis, the Biden administration's brief, recently filed in federal district court, argues that the lease the Trump administration granted to ConocoPhillips is "valid"--including its impacts on the climate.

Given the dire threat we face, it cannot comport with any rationale for supporting ConocoPhillips.

Not surprisingly, the decision drew applause from ConocoPhillips Alaska President Erec Isaacson. The 23.4-million-acre reserve, on Alaska's central north coast, and under the control of the Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management, was created in 1923 in case the Navy needed emergency oil.

Nearly a century later, that need has been outstripped by the need to leave as much oil in the ground as possible. In an Earth Day fact sheet in April, the Biden administration said it is setting the nation on a firm path toward cutting emissions in half over the next nine years, a carbon-free power sector by 2035 and net zero emissions by 2050. "The United States is not waiting, the costs of delay are too great, and our nation is resolved to act now," the fact sheet said. "Climate change poses an existential threat."

Given the dire threat we face, it cannot comport with any rationale for supporting ConocoPhillips. The project would make a mockery of being on a firm path in cutting emissions when the government itself says the project might spew 260 million metric tons of global warming emissions into the atmosphere over the next 30 years, equivalent to the annual emissions from 63 coal-fired plants.

The drilling would also threaten extremely fragile ecosystems for some of the world's greatest concentrations of nesting and migrating wildlife. While less publicized than the 19.3-million-acre Arctic National Wildlife Refuge along the northeast coast run by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the NPR is home to a dazzling array of polar bears, seals, walruses, loons, shorebirds, caribou, and peregrine falcons.

Climate change poses such an existential threat that this spring the International Energy Agency--the intergovernmental energy analysis forum for members of the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation--said all nations must act now. With global carbon dioxide emissions rising again as many COVID-19 restrictions end, the IEA said 2021 is a "critical year at the start of a critical decade" to commit to a "total transformation" of energy. It warned that achieving net zero emissions "hinges on a singular, unwavering focus," adding that: "There is no need for investment in new fossil fuel supply."

The wavering by the Biden administration on extracting the nation from fossil fuel extraction threatens to neuter the many good things the administration is doing, such as suspending the Trump administration's leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, opposing the now-canceled Keystone XL pipeline, pausing new oil and gas drilling leases on federal lands (although that effort is now tangled in a court case), and bringing the United States back into the Paris climate accords.

Other actions and inactions are also concerning. Aside from upholding the Trump administration's permit for ConocoPhillips, the Biden White House whiffed on shutting down the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline until it could be fully reviewed. Particularly contentious to Indigenous tribes is how the pipeline, which carries oil from North Dakota to Illinois, goes under a reservoir of the Missouri River near the Standing Rock reservation. The administration has also taken no position so far on the proposed expansion of Enbridge's Line 3 pipeline, that would bring Canadian tar-sands oil through ecologically sensitive parts of Minnesota and tribal lands.

The complicated, partisan web of politics offers a probable reason why the Biden administration is not going all out to fight climate change from the start. The ConocoPhillips project is championed by Alaska Senators Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan, both of whom were among the few Republicans to vote to confirm Interior Secretary Deb Haaland. Murkowski is also one of the tiny handful of Republican senators who has been known to very occasionally vote with Democrats on major legislation.

Just as sticky on the Democratic side are politicians such as West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin. In a Senate split 50-50 along party lines, Manchin (along with Murkowski) already hampered the Biden administration's carbon mitigation efforts by nixing Elizabeth Klein, Biden's first choice to be deputy energy secretary, complaining that she wasn't friendly enough with the oil and gas industry.

Manchin, the chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, supported the replacement nominee, Tommy Beaudreau, who was approved by the committee for a Senate confirmation vote by an 18-1 margin. As a lawyer, Beaudreau has represented the development of offshore wind and the fossil fuel industry, leading Manchin to describe him as someone whom both sides of the aisle "can work with."

Concern about the Biden administration's record to date prompted several environmental groups wrote a June 10 letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland urging her and the Biden administration to halt new drilling permits and cancel any oil and gas leases that were unlawfully rushed through by the Trump administration.

While diplomatically praising the Biden administration's general climate leadership in a press release, the signatories to the letter were adamant about the need for more action now. One of them, Natasha Leger, executive director of the Citizens for a Healthy Community, said, "The Biden administration needs to stop the federal government's complicity in climate degradation by ending new oil and gas leasing and permitting on federal lands."

President Biden may be trying to avoid drawing a line in the sand, but it's looking likely that one may be forced upon him by his base. Back when he was vice president, the Obama White House, pushed an "all-of-the-above" energy strategy. Then-Vice President Biden presided during a period when rapid growth of fracked natural gas supplanted coal, which helped to slash overall global warming emissions in the United States. But those positive effects are now in the past; natural gas and its primary component, methane, are now major impediments to fighting climate change.

Even in 2014, then-Vice President Biden recognized that the time was coming for the nation to say no to any new fossil fuels. In a speech that year to a Goldman Sachs energy summit, he said, "What is the long play? To state the obvious, I'm not an investment banker, but I wouldn't go long on investments that lead to carbon pollution. I'd bid a little more on clean energy. There's a convergence around addressing climate change and carbon emissions, both here and abroad."

President Biden now has his chance to say no. The time for the long play is here and the opportunity won't last.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

It just takes common sense to see that the climate change math of the Biden administration is not adding up: You cannot approve massive oil drilling projects if you want to swiftly reach net-zero emissions.

That is exactly what the administration did when it sided with ConocoPhillips in the company's bid to drill for more than a half billion barrels of oil in the National Petroleum Reserve (NPR) in the Alaskan Arctic, erecting infrastructure that will be in operation for 30 years or more. After spending $6 million in federal funds and generating more than 3,600 pages of environmental analysis, the Biden administration's brief, recently filed in federal district court, argues that the lease the Trump administration granted to ConocoPhillips is "valid"--including its impacts on the climate.

Given the dire threat we face, it cannot comport with any rationale for supporting ConocoPhillips.

Not surprisingly, the decision drew applause from ConocoPhillips Alaska President Erec Isaacson. The 23.4-million-acre reserve, on Alaska's central north coast, and under the control of the Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management, was created in 1923 in case the Navy needed emergency oil.

Nearly a century later, that need has been outstripped by the need to leave as much oil in the ground as possible. In an Earth Day fact sheet in April, the Biden administration said it is setting the nation on a firm path toward cutting emissions in half over the next nine years, a carbon-free power sector by 2035 and net zero emissions by 2050. "The United States is not waiting, the costs of delay are too great, and our nation is resolved to act now," the fact sheet said. "Climate change poses an existential threat."

Given the dire threat we face, it cannot comport with any rationale for supporting ConocoPhillips. The project would make a mockery of being on a firm path in cutting emissions when the government itself says the project might spew 260 million metric tons of global warming emissions into the atmosphere over the next 30 years, equivalent to the annual emissions from 63 coal-fired plants.

The drilling would also threaten extremely fragile ecosystems for some of the world's greatest concentrations of nesting and migrating wildlife. While less publicized than the 19.3-million-acre Arctic National Wildlife Refuge along the northeast coast run by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the NPR is home to a dazzling array of polar bears, seals, walruses, loons, shorebirds, caribou, and peregrine falcons.

Climate change poses such an existential threat that this spring the International Energy Agency--the intergovernmental energy analysis forum for members of the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation--said all nations must act now. With global carbon dioxide emissions rising again as many COVID-19 restrictions end, the IEA said 2021 is a "critical year at the start of a critical decade" to commit to a "total transformation" of energy. It warned that achieving net zero emissions "hinges on a singular, unwavering focus," adding that: "There is no need for investment in new fossil fuel supply."

The wavering by the Biden administration on extracting the nation from fossil fuel extraction threatens to neuter the many good things the administration is doing, such as suspending the Trump administration's leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, opposing the now-canceled Keystone XL pipeline, pausing new oil and gas drilling leases on federal lands (although that effort is now tangled in a court case), and bringing the United States back into the Paris climate accords.

Other actions and inactions are also concerning. Aside from upholding the Trump administration's permit for ConocoPhillips, the Biden White House whiffed on shutting down the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline until it could be fully reviewed. Particularly contentious to Indigenous tribes is how the pipeline, which carries oil from North Dakota to Illinois, goes under a reservoir of the Missouri River near the Standing Rock reservation. The administration has also taken no position so far on the proposed expansion of Enbridge's Line 3 pipeline, that would bring Canadian tar-sands oil through ecologically sensitive parts of Minnesota and tribal lands.

The complicated, partisan web of politics offers a probable reason why the Biden administration is not going all out to fight climate change from the start. The ConocoPhillips project is championed by Alaska Senators Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan, both of whom were among the few Republicans to vote to confirm Interior Secretary Deb Haaland. Murkowski is also one of the tiny handful of Republican senators who has been known to very occasionally vote with Democrats on major legislation.

Just as sticky on the Democratic side are politicians such as West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin. In a Senate split 50-50 along party lines, Manchin (along with Murkowski) already hampered the Biden administration's carbon mitigation efforts by nixing Elizabeth Klein, Biden's first choice to be deputy energy secretary, complaining that she wasn't friendly enough with the oil and gas industry.

Manchin, the chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, supported the replacement nominee, Tommy Beaudreau, who was approved by the committee for a Senate confirmation vote by an 18-1 margin. As a lawyer, Beaudreau has represented the development of offshore wind and the fossil fuel industry, leading Manchin to describe him as someone whom both sides of the aisle "can work with."

Concern about the Biden administration's record to date prompted several environmental groups wrote a June 10 letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland urging her and the Biden administration to halt new drilling permits and cancel any oil and gas leases that were unlawfully rushed through by the Trump administration.

While diplomatically praising the Biden administration's general climate leadership in a press release, the signatories to the letter were adamant about the need for more action now. One of them, Natasha Leger, executive director of the Citizens for a Healthy Community, said, "The Biden administration needs to stop the federal government's complicity in climate degradation by ending new oil and gas leasing and permitting on federal lands."

President Biden may be trying to avoid drawing a line in the sand, but it's looking likely that one may be forced upon him by his base. Back when he was vice president, the Obama White House, pushed an "all-of-the-above" energy strategy. Then-Vice President Biden presided during a period when rapid growth of fracked natural gas supplanted coal, which helped to slash overall global warming emissions in the United States. But those positive effects are now in the past; natural gas and its primary component, methane, are now major impediments to fighting climate change.

Even in 2014, then-Vice President Biden recognized that the time was coming for the nation to say no to any new fossil fuels. In a speech that year to a Goldman Sachs energy summit, he said, "What is the long play? To state the obvious, I'm not an investment banker, but I wouldn't go long on investments that lead to carbon pollution. I'd bid a little more on clean energy. There's a convergence around addressing climate change and carbon emissions, both here and abroad."

President Biden now has his chance to say no. The time for the long play is here and the opportunity won't last.

It just takes common sense to see that the climate change math of the Biden administration is not adding up: You cannot approve massive oil drilling projects if you want to swiftly reach net-zero emissions.

That is exactly what the administration did when it sided with ConocoPhillips in the company's bid to drill for more than a half billion barrels of oil in the National Petroleum Reserve (NPR) in the Alaskan Arctic, erecting infrastructure that will be in operation for 30 years or more. After spending $6 million in federal funds and generating more than 3,600 pages of environmental analysis, the Biden administration's brief, recently filed in federal district court, argues that the lease the Trump administration granted to ConocoPhillips is "valid"--including its impacts on the climate.

Given the dire threat we face, it cannot comport with any rationale for supporting ConocoPhillips.

Not surprisingly, the decision drew applause from ConocoPhillips Alaska President Erec Isaacson. The 23.4-million-acre reserve, on Alaska's central north coast, and under the control of the Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management, was created in 1923 in case the Navy needed emergency oil.

Nearly a century later, that need has been outstripped by the need to leave as much oil in the ground as possible. In an Earth Day fact sheet in April, the Biden administration said it is setting the nation on a firm path toward cutting emissions in half over the next nine years, a carbon-free power sector by 2035 and net zero emissions by 2050. "The United States is not waiting, the costs of delay are too great, and our nation is resolved to act now," the fact sheet said. "Climate change poses an existential threat."

Given the dire threat we face, it cannot comport with any rationale for supporting ConocoPhillips. The project would make a mockery of being on a firm path in cutting emissions when the government itself says the project might spew 260 million metric tons of global warming emissions into the atmosphere over the next 30 years, equivalent to the annual emissions from 63 coal-fired plants.

The drilling would also threaten extremely fragile ecosystems for some of the world's greatest concentrations of nesting and migrating wildlife. While less publicized than the 19.3-million-acre Arctic National Wildlife Refuge along the northeast coast run by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the NPR is home to a dazzling array of polar bears, seals, walruses, loons, shorebirds, caribou, and peregrine falcons.

Climate change poses such an existential threat that this spring the International Energy Agency--the intergovernmental energy analysis forum for members of the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation--said all nations must act now. With global carbon dioxide emissions rising again as many COVID-19 restrictions end, the IEA said 2021 is a "critical year at the start of a critical decade" to commit to a "total transformation" of energy. It warned that achieving net zero emissions "hinges on a singular, unwavering focus," adding that: "There is no need for investment in new fossil fuel supply."

The wavering by the Biden administration on extracting the nation from fossil fuel extraction threatens to neuter the many good things the administration is doing, such as suspending the Trump administration's leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, opposing the now-canceled Keystone XL pipeline, pausing new oil and gas drilling leases on federal lands (although that effort is now tangled in a court case), and bringing the United States back into the Paris climate accords.

Other actions and inactions are also concerning. Aside from upholding the Trump administration's permit for ConocoPhillips, the Biden White House whiffed on shutting down the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline until it could be fully reviewed. Particularly contentious to Indigenous tribes is how the pipeline, which carries oil from North Dakota to Illinois, goes under a reservoir of the Missouri River near the Standing Rock reservation. The administration has also taken no position so far on the proposed expansion of Enbridge's Line 3 pipeline, that would bring Canadian tar-sands oil through ecologically sensitive parts of Minnesota and tribal lands.

The complicated, partisan web of politics offers a probable reason why the Biden administration is not going all out to fight climate change from the start. The ConocoPhillips project is championed by Alaska Senators Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan, both of whom were among the few Republicans to vote to confirm Interior Secretary Deb Haaland. Murkowski is also one of the tiny handful of Republican senators who has been known to very occasionally vote with Democrats on major legislation.

Just as sticky on the Democratic side are politicians such as West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin. In a Senate split 50-50 along party lines, Manchin (along with Murkowski) already hampered the Biden administration's carbon mitigation efforts by nixing Elizabeth Klein, Biden's first choice to be deputy energy secretary, complaining that she wasn't friendly enough with the oil and gas industry.

Manchin, the chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, supported the replacement nominee, Tommy Beaudreau, who was approved by the committee for a Senate confirmation vote by an 18-1 margin. As a lawyer, Beaudreau has represented the development of offshore wind and the fossil fuel industry, leading Manchin to describe him as someone whom both sides of the aisle "can work with."

Concern about the Biden administration's record to date prompted several environmental groups wrote a June 10 letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland urging her and the Biden administration to halt new drilling permits and cancel any oil and gas leases that were unlawfully rushed through by the Trump administration.

While diplomatically praising the Biden administration's general climate leadership in a press release, the signatories to the letter were adamant about the need for more action now. One of them, Natasha Leger, executive director of the Citizens for a Healthy Community, said, "The Biden administration needs to stop the federal government's complicity in climate degradation by ending new oil and gas leasing and permitting on federal lands."

President Biden may be trying to avoid drawing a line in the sand, but it's looking likely that one may be forced upon him by his base. Back when he was vice president, the Obama White House, pushed an "all-of-the-above" energy strategy. Then-Vice President Biden presided during a period when rapid growth of fracked natural gas supplanted coal, which helped to slash overall global warming emissions in the United States. But those positive effects are now in the past; natural gas and its primary component, methane, are now major impediments to fighting climate change.

Even in 2014, then-Vice President Biden recognized that the time was coming for the nation to say no to any new fossil fuels. In a speech that year to a Goldman Sachs energy summit, he said, "What is the long play? To state the obvious, I'm not an investment banker, but I wouldn't go long on investments that lead to carbon pollution. I'd bid a little more on clean energy. There's a convergence around addressing climate change and carbon emissions, both here and abroad."

President Biden now has his chance to say no. The time for the long play is here and the opportunity won't last.