According to a White House analysis (9/23/21), the country's 400 wealthiest families have an effective tax rate of just over 8%. At the New York Times (9/23/21), reporter Jim Tankersley was quick to cast doubt on the figure.

According to Tankersley's framing, the analysis "seeks to show a gap between the tax rate that everyday Americans face and what the richest owe on their vast holdings," and is "an attempt to bolster Mr. Biden's claims that billionaires are not paying what they actually should owe in federal taxes, and that the tax code rewards wealth, not work" (emphasis added). In other words, it's an analysis with a political agenda.

Dubious data point

This is in contrast to "most measures of tax rates," which "do not use the White House method of counting asset gains as annual income." The piece emphasizes how "unconventional" the White House analysis is, and that it's "well below what other analyses have found." (Note that these analyses don't "seek to show," but simply "find," thus enhancing their social science credibility.)

Tankersley points to one data point here:

The independent Tax Policy Center in Washington estimated this year that in 2015, the highest-earning 1,400 households in the country paid an average effective tax rate of about 24%, compared with an average rate of about 14% for all taxpayers.

First, that "most" measures don't count asset gains says more about how thoroughly the rich have rigged the tax code to exclude most of their income than it does about how one ought to measure income--or tax rates. The Tax Policy Center figure, for instance, only considers federal income tax, which ignores state and local income tax, as well as payroll, consumption and excise taxes.

Second, the "independent" Tax Policy Center should hardly be assumed to be agenda-free; according to its most recent annual report (2017) available online, the group's "Leadership Committee" includes representatives of major financial firms like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and the Carlyle Group, entities that have a direct stake in keeping gains in financial assets from being counted as income.

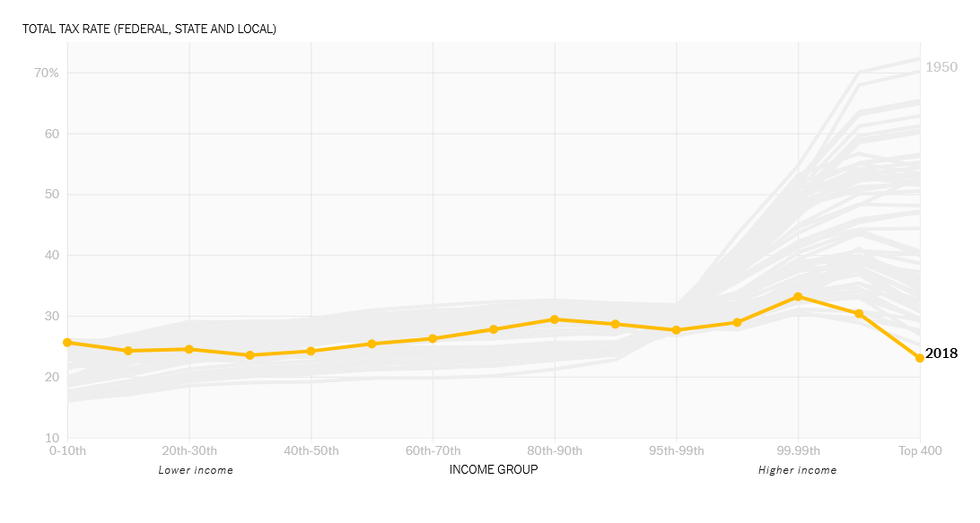

And third, it's crucial that the data from the Tax Policy Center comes from 2015, since that was before the 2017 Trump tax cuts slashed taxes even further for the ultra-rich. As New YorkTimes columnist David Leonhardt (10/6/19) pointed out in 2019, the tax cuts "helped push the tax rate on the 400 wealthiest households below the rates for almost everyone else" in 2018, to 23% for the wealthiest versus 28% for the average taxpayer.

Top tax rates have been pushed so far down over the last 70 years that the richest households now pay a lower percentage than any other income group (New York Times, 10/6/19).

Victory for the richest

It's a remarkable victory for the rich over the rest of us: The richest Americans had an effective tax rate of 70% in 1950 and 47% in 1980. Meanwhile, the average taxpayer has seen relatively little change in their effective tax rate over the same period.

That's all according to University of California/Berkeley economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman (Triumph of Justice, 2019), who were not using the "unconventional" White House method of dividing taxes paid by total asset gains. They were, however, using the White House method of looking at the top 400 as measured by wealth, rather than the top 1,400 as measured by adjusted gross income. They were also considering all taxes, including payroll tax (Social Security and Medicare), state income tax, and consumption and excise taxes.

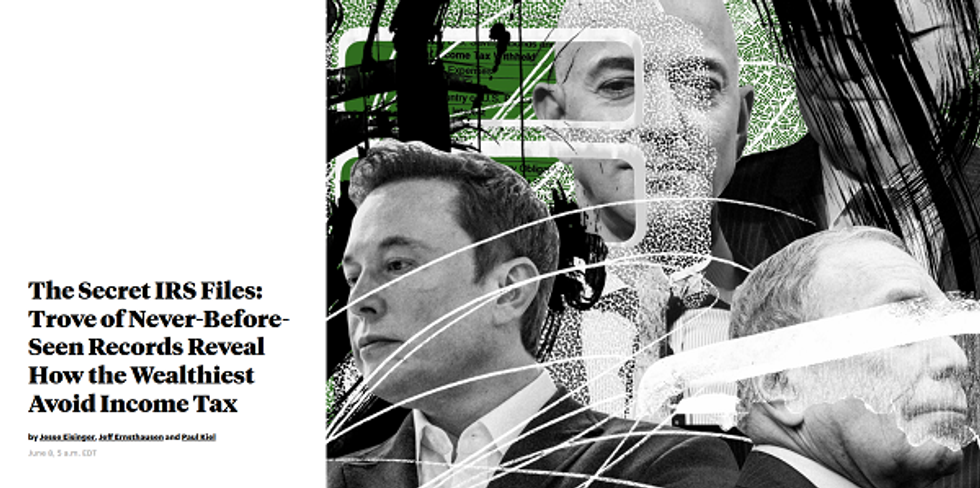

ProPublica (6/8/21) "compared how much in taxes the 25 richest Americans paid each year to how much Forbes estimated their wealth grew in that same time period"--an obvious precedent for the White House analysis that was overlooked by the New York Times.

If you want to look at what the very richest Americans pay in taxes, then the way Saez/Zucman and the White House do it is more accurate than the way the Tax Policy Center does it, because those 400 billionaires--worth a combined $3.2 trillion last year, up $240 billion from the year prior, as calculated annually by Forbes--are very often not those with the highest taxable income.

For instance, Warren Buffett, a perennial Forbes 400 member who currently ranks No. 4, voluntarily released his tax returns in 2015. His reported income ($11.6 million) didn't even put him in the top 14,000 earners. That year, Buffett paid about 16% of his reported income in taxes.

Buffett released his returns in response to Trump's attempt to deflect attention from his own refusal to release his returns; Buffett had nothing to hide, since his methods of avoiding taxes were perfectly legal.

As ProPublica (6/8/21) found in its recent bombshell report on leaked tax returns of the ultra-rich--yet another analysis using similar methods to the White House that went unacknowledged by Tankersley--Buffett is particularly good at tax avoidance: From 2014-18, while his wealth grew by over $24 billion, he managed to pay less than $24 million in taxes. It's an effective tax rate of 19% on reported income measured the "conventional" way, but a tax rate of just 0.1% on his actual gains. That's the lowest of any of the country's billionaires.

Mind-boggling methods

The ultra-rich have a myriad of mind-boggling ways of getting away with not paying taxes that the rest of us have to. Two that the Biden administration is pushing to eliminate relate to asset gains.

If someone sells a stock, any gains from the purchase price are taxed at a significantly lower rate than other income; the White House is seeking to end that preferential treatment for those earning above $1 million.

Further, if someone instead holds that stock until they die, and leaves it to an heir, those gains are not taxed. So billionaires like Buffett and Jeff Bezos can vastly increase their wealth, never pay taxes on most of it as long as they don't sell it, pass those assets to their children upon their death and--poof!--those billions are never subject to income tax. This dodge is called the stepped-up basis, and it's a major driver of the racial wealth gap.

Lawmakers impacted

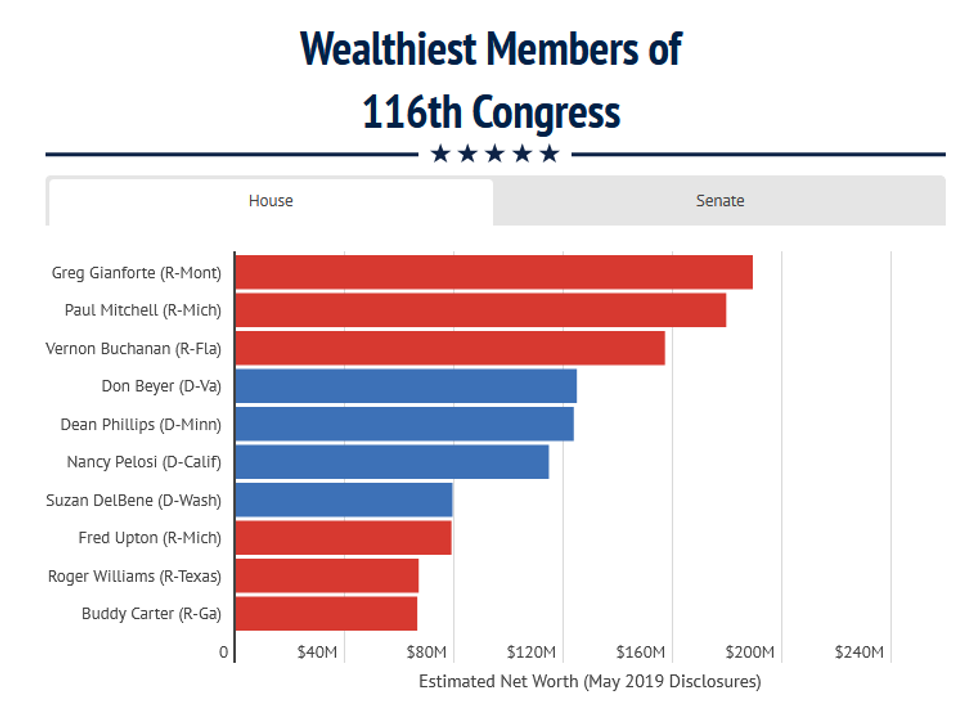

As Open Secrets (4/23/20) points out, many lawmakers have a direct interest in avoiding taxes on wealth.

Most people don't think the wealthy--or corporations--pay their fair share of taxes (Pew, 4/30/21). But their representatives aren't eager to fix the system. Tankersley mentioned at the end of his piece that congressional Democrats have "pushed back" on Biden's efforts to change both capital gains taxes and the stepped-up basis. He didn't mention how many Democrats would be directly negatively impacted by those fixes.

Given that the majority of members of the last Congress were millionaires (Open Secrets, 4/23/20), any children they have will greatly benefit from the stepped-up basis. And any member of Congress who holds stock and ever plans to sell any of it is impacted by increases in the capital gains tax. Not to mention all the wealthy donors funneling money into super PACs for most Congress members.

Fortunately for them, they've got the New York Times running interference.