SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

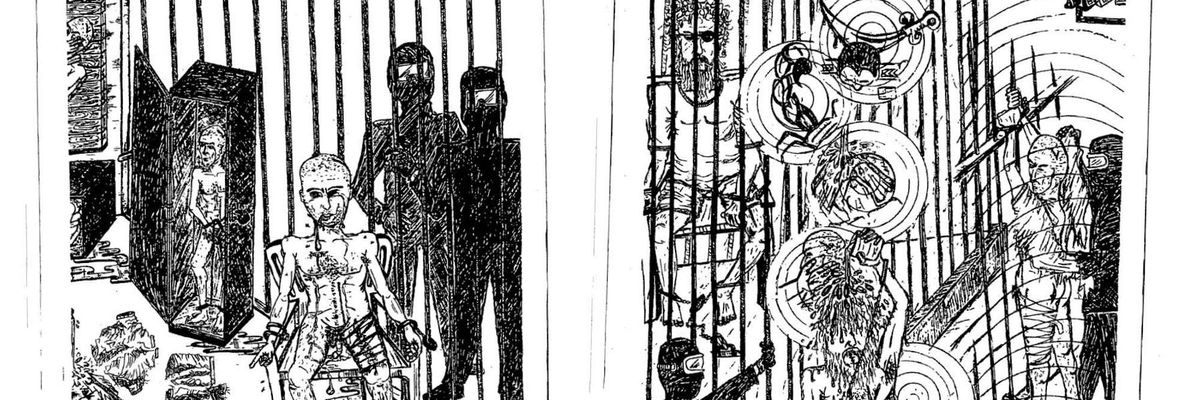

Abu Zubaydah's drawings, which were made while he was in U.S. custody. These are two of eight drawings released by the CIA. (Image: CIA/ProPublica)

One of the longest-held prisoners in the U.S. global war on terror is finally getting a day in court. Sort of. The prisoner, Abu Zubaydah, who has never been charged with a crime, has been waiting 14 years for a federal judge to rule on his habeas corpus petition that challenges the legality of his detention. But next week, the Supreme Court will hear arguments on a separate case: Zubaydah's request that he be permitted to take testimony from the two CIA contractors who oversaw his torture.

The European Court for Human Rights ruled in 2015 that it was "beyond a reasonable doubt" that Zubaydah had been held in Poland... Warsaw asked Washington for assistance. Their request went unanswered.

The Trump administration intervened to block public disclosure about how Zubaydah was treated while in U.S. custody, or even where he was held, and the Biden administration is continuing the fight. In its Supreme Court briefs, the administration has cited an array of arguments against allowing the two men to be deposed, citing everything from the state secrets privilege, which shields highly sensitive government information from being revealed in civil litigation, to the plot of the Oscar-winning thriller "Argo."

Zubaydah's case has reached the Supreme Court circuitously, beginning with an investigation in Poland five years ago into whether any of its government officials were complicit in Zubaydah's detention and torture. The United States has refused to cooperate with the Polish prosecutors, citing national security concerns.

The Polish investigators asked for help from Zubaydah's lawyer, who in turn sought to take the depositions of psychologists James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen. Paid more than $80 million, they were the principal architects of the CIA's "enhanced interrogation techniques" -- the agency's euphemism for waterboarding prisoners, slamming them against walls, forcing them into a coffin-sized box, depriving them of sleep for days at a time and other forms of torture. Zubaydah was the first prisoner on whom Mitchell and Jessen tested their techniques, according to a Senate Intelligence Committee report released in 2014.

After the CIA seized Zubaydah in Pakistan in March 2002 and secretly took him to a black site in Thailand, Bush administration officials asserted that he was al-Qaida's third-highest-ranking leader. The government has since acknowledged that he was not a senior terrorist leader and that he had no known connection to the 9/11 attacks. He had been in and out of Afghanistan and Pakistan for nearly a decade and had suffered a serious head injury while fighting against the Soviet-backed government. Intelligence officials concluded he was more of a facilitator, providing false passports, housing and other arrangements for men, some potential terrorists, who moved between the two countries.

"He wasn't hatching plots and giving orders," Robert Grenier, the CIA station chief in Islamabad when Zubaydah was being monitored and eventually seized, wrote in his book "88 Days to Kandahar." "I did not expect that he would know the time or place of the next attack." However, in Washington, CIA officials were convinced that Zubaydah knew about plans to attack the United States, and Mitchell was determined to extract the information, according to declassified documents.

After being waterboarded 83 times in Thailand, Zubaydah had still not revealed any "actionable intelligence," cables from Thailand to Langley reported. Later, interrogators would conclude he knew nothing about al-Qaida's plans.

He did, however, send FBI agents on futile investigations as he tried to end the torture. At one point, interrogators in Thailand asked Zubaydah a hypothetical question: If you were going to carry out an attack in the United States, where would you do it? The Statue of Liberty and the Brooklyn Bridge, Zubaydah answered. This led New York City to impose security measures "not seen since the first months after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks," The New York Times reported.

In December 2002, when journalists began asking questions about a black site in Thailand, it was shut down, and Zubaydah was secretly transferred to Poland.

For years, the Polish government denied the existence of a CIA detention site. But after the 2014 Senate Intelligence report and after the European Court for Human Rights ruled in 2015 that it was "beyond a reasonable doubt" that Zubaydah had been held in Poland, Polish prosecutors began their investigation. Invoking a mutual legal assistance treaty, which commits each country to support the other's criminal investigations, Warsaw asked Washington for assistance. Their request went unanswered.

Joseph Margulies, one of Zubaydah's American lawyers, realized that the Polish investigation offered an opportunity to make public at least some of what had been done to his client at the black sites and might lead to his release. Invoking a federal law that allows an interested party to gather evidence in support of a foreign investigation, he asked a court to compel the depositions of Mitchell and Jessen. The Trump administration immediately intervened. It asserted the state secrets privilege to block the depositions, contending that the testimony would formally confirm or deny that the CIA operated a clandestine detention center in Poland.

As the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a nonprofit organization in London, put it in a brief recently filed with the Supreme Court in support of Zubaydah, "Study after study, report after report, emerging from the CIA, DOJ and SSCI, along with flight record after flight record, flight invoice after invoice, have confirmed, in graphic and granular detail, what the world already knows: that the CIA had black sites in Thailand, Poland, Romania, Lithuania, Afghanistan and Guantanamo Bay."

Even the former Polish President Aleksander Kwasniewski has acknowledged that the CIA had set up a black site in his country. "Of course, everything took place with my knowledge," he told Poland's leading newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza, in 2012. "The President and the Prime Minister agreed to the intelligence co-operation with the Americans, because this was what was required by national interest."

None of this has slowed the U.S. government's efforts to avoid acknowledging what is now accepted fact. In their briefs, government lawyers argue that the Polish site, if it ever existed, remains a state secret because the federal government has never officially admitted to its existence. They contend that all those public reports and statements could be part of a CIA disinformation campaign. The lawyers cite as evidence the book and movie "Argo," which chronicles how the CIA rescued Americans hiding out in Iran by posing as a film crew. (As many commentators pointed out, the movie takes considerable liberties with the facts, adding, among other things, a chase through an airport that never occurred.)

The government's Supreme Court brief relies primarily on United States v. Reynolds, a 1953 case regarding the crash of an Air Force B-29 near Waycross, Georgia. When the families of three civilian engineers killed in the crash sought a copy of the accident report and witness statements, the Air Force refused to turn over the documents, asserting that they contained classified information about a secret mission. In a landmark decision, the Supreme Court upheld the government's claim and, for the first time, formally recognized the state secrets privilege.

Forty-seven years later, the Air Force declassified the documents. They contained no reference to a secret mission. "Instead, the report told a horror story of incompetence, bungling, and tragic error," Garry Wills wrote in The New York Review of Books.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

One of the longest-held prisoners in the U.S. global war on terror is finally getting a day in court. Sort of. The prisoner, Abu Zubaydah, who has never been charged with a crime, has been waiting 14 years for a federal judge to rule on his habeas corpus petition that challenges the legality of his detention. But next week, the Supreme Court will hear arguments on a separate case: Zubaydah's request that he be permitted to take testimony from the two CIA contractors who oversaw his torture.

The European Court for Human Rights ruled in 2015 that it was "beyond a reasonable doubt" that Zubaydah had been held in Poland... Warsaw asked Washington for assistance. Their request went unanswered.

The Trump administration intervened to block public disclosure about how Zubaydah was treated while in U.S. custody, or even where he was held, and the Biden administration is continuing the fight. In its Supreme Court briefs, the administration has cited an array of arguments against allowing the two men to be deposed, citing everything from the state secrets privilege, which shields highly sensitive government information from being revealed in civil litigation, to the plot of the Oscar-winning thriller "Argo."

Zubaydah's case has reached the Supreme Court circuitously, beginning with an investigation in Poland five years ago into whether any of its government officials were complicit in Zubaydah's detention and torture. The United States has refused to cooperate with the Polish prosecutors, citing national security concerns.

The Polish investigators asked for help from Zubaydah's lawyer, who in turn sought to take the depositions of psychologists James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen. Paid more than $80 million, they were the principal architects of the CIA's "enhanced interrogation techniques" -- the agency's euphemism for waterboarding prisoners, slamming them against walls, forcing them into a coffin-sized box, depriving them of sleep for days at a time and other forms of torture. Zubaydah was the first prisoner on whom Mitchell and Jessen tested their techniques, according to a Senate Intelligence Committee report released in 2014.

After the CIA seized Zubaydah in Pakistan in March 2002 and secretly took him to a black site in Thailand, Bush administration officials asserted that he was al-Qaida's third-highest-ranking leader. The government has since acknowledged that he was not a senior terrorist leader and that he had no known connection to the 9/11 attacks. He had been in and out of Afghanistan and Pakistan for nearly a decade and had suffered a serious head injury while fighting against the Soviet-backed government. Intelligence officials concluded he was more of a facilitator, providing false passports, housing and other arrangements for men, some potential terrorists, who moved between the two countries.

"He wasn't hatching plots and giving orders," Robert Grenier, the CIA station chief in Islamabad when Zubaydah was being monitored and eventually seized, wrote in his book "88 Days to Kandahar." "I did not expect that he would know the time or place of the next attack." However, in Washington, CIA officials were convinced that Zubaydah knew about plans to attack the United States, and Mitchell was determined to extract the information, according to declassified documents.

After being waterboarded 83 times in Thailand, Zubaydah had still not revealed any "actionable intelligence," cables from Thailand to Langley reported. Later, interrogators would conclude he knew nothing about al-Qaida's plans.

He did, however, send FBI agents on futile investigations as he tried to end the torture. At one point, interrogators in Thailand asked Zubaydah a hypothetical question: If you were going to carry out an attack in the United States, where would you do it? The Statue of Liberty and the Brooklyn Bridge, Zubaydah answered. This led New York City to impose security measures "not seen since the first months after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks," The New York Times reported.

In December 2002, when journalists began asking questions about a black site in Thailand, it was shut down, and Zubaydah was secretly transferred to Poland.

For years, the Polish government denied the existence of a CIA detention site. But after the 2014 Senate Intelligence report and after the European Court for Human Rights ruled in 2015 that it was "beyond a reasonable doubt" that Zubaydah had been held in Poland, Polish prosecutors began their investigation. Invoking a mutual legal assistance treaty, which commits each country to support the other's criminal investigations, Warsaw asked Washington for assistance. Their request went unanswered.

Joseph Margulies, one of Zubaydah's American lawyers, realized that the Polish investigation offered an opportunity to make public at least some of what had been done to his client at the black sites and might lead to his release. Invoking a federal law that allows an interested party to gather evidence in support of a foreign investigation, he asked a court to compel the depositions of Mitchell and Jessen. The Trump administration immediately intervened. It asserted the state secrets privilege to block the depositions, contending that the testimony would formally confirm or deny that the CIA operated a clandestine detention center in Poland.

As the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a nonprofit organization in London, put it in a brief recently filed with the Supreme Court in support of Zubaydah, "Study after study, report after report, emerging from the CIA, DOJ and SSCI, along with flight record after flight record, flight invoice after invoice, have confirmed, in graphic and granular detail, what the world already knows: that the CIA had black sites in Thailand, Poland, Romania, Lithuania, Afghanistan and Guantanamo Bay."

Even the former Polish President Aleksander Kwasniewski has acknowledged that the CIA had set up a black site in his country. "Of course, everything took place with my knowledge," he told Poland's leading newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza, in 2012. "The President and the Prime Minister agreed to the intelligence co-operation with the Americans, because this was what was required by national interest."

None of this has slowed the U.S. government's efforts to avoid acknowledging what is now accepted fact. In their briefs, government lawyers argue that the Polish site, if it ever existed, remains a state secret because the federal government has never officially admitted to its existence. They contend that all those public reports and statements could be part of a CIA disinformation campaign. The lawyers cite as evidence the book and movie "Argo," which chronicles how the CIA rescued Americans hiding out in Iran by posing as a film crew. (As many commentators pointed out, the movie takes considerable liberties with the facts, adding, among other things, a chase through an airport that never occurred.)

The government's Supreme Court brief relies primarily on United States v. Reynolds, a 1953 case regarding the crash of an Air Force B-29 near Waycross, Georgia. When the families of three civilian engineers killed in the crash sought a copy of the accident report and witness statements, the Air Force refused to turn over the documents, asserting that they contained classified information about a secret mission. In a landmark decision, the Supreme Court upheld the government's claim and, for the first time, formally recognized the state secrets privilege.

Forty-seven years later, the Air Force declassified the documents. They contained no reference to a secret mission. "Instead, the report told a horror story of incompetence, bungling, and tragic error," Garry Wills wrote in The New York Review of Books.

One of the longest-held prisoners in the U.S. global war on terror is finally getting a day in court. Sort of. The prisoner, Abu Zubaydah, who has never been charged with a crime, has been waiting 14 years for a federal judge to rule on his habeas corpus petition that challenges the legality of his detention. But next week, the Supreme Court will hear arguments on a separate case: Zubaydah's request that he be permitted to take testimony from the two CIA contractors who oversaw his torture.

The European Court for Human Rights ruled in 2015 that it was "beyond a reasonable doubt" that Zubaydah had been held in Poland... Warsaw asked Washington for assistance. Their request went unanswered.

The Trump administration intervened to block public disclosure about how Zubaydah was treated while in U.S. custody, or even where he was held, and the Biden administration is continuing the fight. In its Supreme Court briefs, the administration has cited an array of arguments against allowing the two men to be deposed, citing everything from the state secrets privilege, which shields highly sensitive government information from being revealed in civil litigation, to the plot of the Oscar-winning thriller "Argo."

Zubaydah's case has reached the Supreme Court circuitously, beginning with an investigation in Poland five years ago into whether any of its government officials were complicit in Zubaydah's detention and torture. The United States has refused to cooperate with the Polish prosecutors, citing national security concerns.

The Polish investigators asked for help from Zubaydah's lawyer, who in turn sought to take the depositions of psychologists James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen. Paid more than $80 million, they were the principal architects of the CIA's "enhanced interrogation techniques" -- the agency's euphemism for waterboarding prisoners, slamming them against walls, forcing them into a coffin-sized box, depriving them of sleep for days at a time and other forms of torture. Zubaydah was the first prisoner on whom Mitchell and Jessen tested their techniques, according to a Senate Intelligence Committee report released in 2014.

After the CIA seized Zubaydah in Pakistan in March 2002 and secretly took him to a black site in Thailand, Bush administration officials asserted that he was al-Qaida's third-highest-ranking leader. The government has since acknowledged that he was not a senior terrorist leader and that he had no known connection to the 9/11 attacks. He had been in and out of Afghanistan and Pakistan for nearly a decade and had suffered a serious head injury while fighting against the Soviet-backed government. Intelligence officials concluded he was more of a facilitator, providing false passports, housing and other arrangements for men, some potential terrorists, who moved between the two countries.

"He wasn't hatching plots and giving orders," Robert Grenier, the CIA station chief in Islamabad when Zubaydah was being monitored and eventually seized, wrote in his book "88 Days to Kandahar." "I did not expect that he would know the time or place of the next attack." However, in Washington, CIA officials were convinced that Zubaydah knew about plans to attack the United States, and Mitchell was determined to extract the information, according to declassified documents.

After being waterboarded 83 times in Thailand, Zubaydah had still not revealed any "actionable intelligence," cables from Thailand to Langley reported. Later, interrogators would conclude he knew nothing about al-Qaida's plans.

He did, however, send FBI agents on futile investigations as he tried to end the torture. At one point, interrogators in Thailand asked Zubaydah a hypothetical question: If you were going to carry out an attack in the United States, where would you do it? The Statue of Liberty and the Brooklyn Bridge, Zubaydah answered. This led New York City to impose security measures "not seen since the first months after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks," The New York Times reported.

In December 2002, when journalists began asking questions about a black site in Thailand, it was shut down, and Zubaydah was secretly transferred to Poland.

For years, the Polish government denied the existence of a CIA detention site. But after the 2014 Senate Intelligence report and after the European Court for Human Rights ruled in 2015 that it was "beyond a reasonable doubt" that Zubaydah had been held in Poland, Polish prosecutors began their investigation. Invoking a mutual legal assistance treaty, which commits each country to support the other's criminal investigations, Warsaw asked Washington for assistance. Their request went unanswered.

Joseph Margulies, one of Zubaydah's American lawyers, realized that the Polish investigation offered an opportunity to make public at least some of what had been done to his client at the black sites and might lead to his release. Invoking a federal law that allows an interested party to gather evidence in support of a foreign investigation, he asked a court to compel the depositions of Mitchell and Jessen. The Trump administration immediately intervened. It asserted the state secrets privilege to block the depositions, contending that the testimony would formally confirm or deny that the CIA operated a clandestine detention center in Poland.

As the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a nonprofit organization in London, put it in a brief recently filed with the Supreme Court in support of Zubaydah, "Study after study, report after report, emerging from the CIA, DOJ and SSCI, along with flight record after flight record, flight invoice after invoice, have confirmed, in graphic and granular detail, what the world already knows: that the CIA had black sites in Thailand, Poland, Romania, Lithuania, Afghanistan and Guantanamo Bay."

Even the former Polish President Aleksander Kwasniewski has acknowledged that the CIA had set up a black site in his country. "Of course, everything took place with my knowledge," he told Poland's leading newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza, in 2012. "The President and the Prime Minister agreed to the intelligence co-operation with the Americans, because this was what was required by national interest."

None of this has slowed the U.S. government's efforts to avoid acknowledging what is now accepted fact. In their briefs, government lawyers argue that the Polish site, if it ever existed, remains a state secret because the federal government has never officially admitted to its existence. They contend that all those public reports and statements could be part of a CIA disinformation campaign. The lawyers cite as evidence the book and movie "Argo," which chronicles how the CIA rescued Americans hiding out in Iran by posing as a film crew. (As many commentators pointed out, the movie takes considerable liberties with the facts, adding, among other things, a chase through an airport that never occurred.)

The government's Supreme Court brief relies primarily on United States v. Reynolds, a 1953 case regarding the crash of an Air Force B-29 near Waycross, Georgia. When the families of three civilian engineers killed in the crash sought a copy of the accident report and witness statements, the Air Force refused to turn over the documents, asserting that they contained classified information about a secret mission. In a landmark decision, the Supreme Court upheld the government's claim and, for the first time, formally recognized the state secrets privilege.

Forty-seven years later, the Air Force declassified the documents. They contained no reference to a secret mission. "Instead, the report told a horror story of incompetence, bungling, and tragic error," Garry Wills wrote in The New York Review of Books.