International negotiators are meeting in Glasgow, Scotland to develop solutions to the climate change threat. But one major obstacle to global sustainability will be largely absent from the discussions: the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) system.

This system gives transnational corporations the power to sue governments over actions--including policies to address climate change--that reduce the value of their foreign investments. Allowing corporations to continue to wield this power could undermine whatever agreements might be reached in Glasgow.

To effectively combat climate change, governments around the world will need the flexibility to pursue a wide range of actions--without the threat of provoking expensive corporate lawsuits.

How does this system work? Clauses in more than 2,600 Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) allow foreign investors to bypass domestic courts and sue sovereign states in international tribunals for millions--and even billions--of dollars.

The World Bank's International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) is the most commonly used of these arbitration tribunals, followed by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). Made up of highly paid, three-person panels of corporate lawyers, these tribunals should not be mistaken for courts of law. This privatized system has little regard for precedent, truth, or justice.

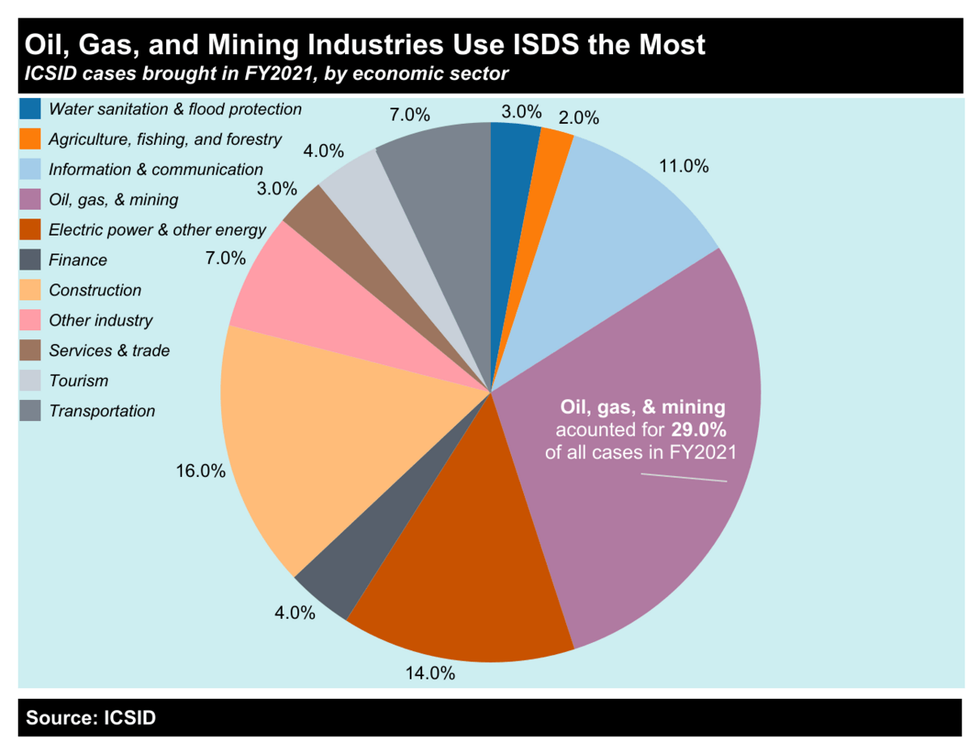

Companies in the highly lucrative natural resource extraction sector take greatest advantage of ISDS. Oil, gas, and mining companies have filed around 25 percent of all known claims to date, and 29 percent of all ICSID claims in fiscal year 2021.

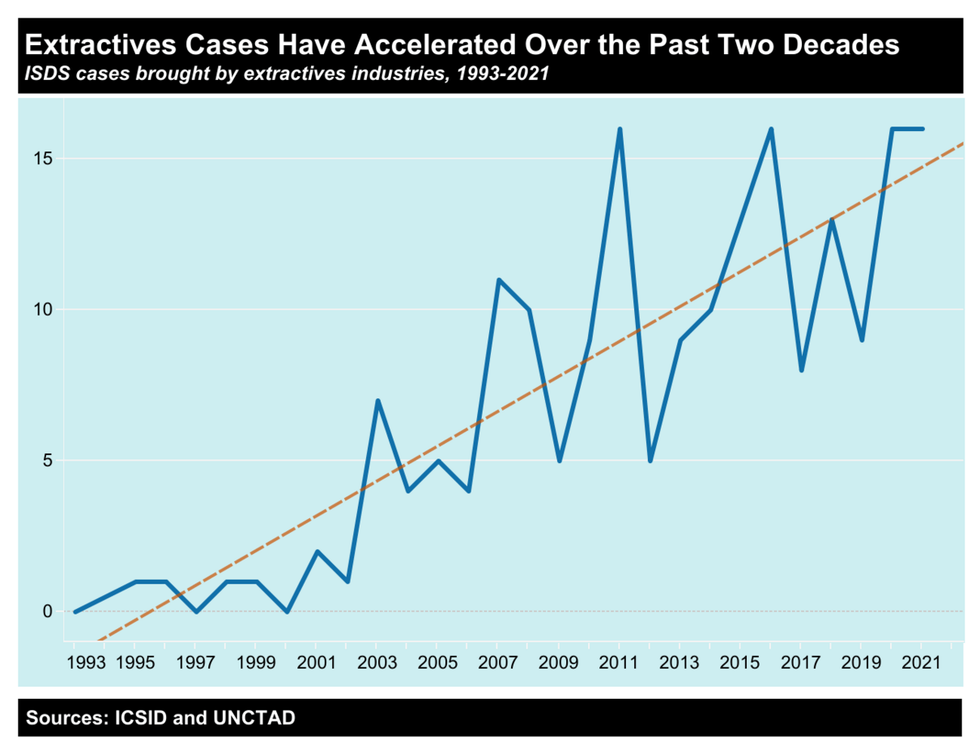

The growth of suits brought by extractive industries has been exponential. Since 1995, when an extractive industry brought their first case under an international agreement, they have brought claims demanding at least $195 billion and won awards totaling at least $73.2 billion. These figures are based on available data from ICSID and UNCTAD. Other arbitration tribunals do not publish information about cases or awards.

Extractives corporations not only use the ISDS system the most, they also receive the largest monetary awards. Out of the 14 known awards for more than $1 billion, 11 pertain to oil, gas and mining.

There are at least 82 known pending ISDS cases brought by extractive industries. Of the 42 where information is available, the companies are demanding a total of $99.1 billion ($71.1 billion by mining companies and $28.1 billion by oil and gas companies).

Notably there are 40 pending cases where the amounts being claimed are not available, so the figures above are only partial. But from the information available there are at least 14 pending cases for more than $1 billion, with ludicrous suits against Congo for $27 billion and Colombia for $16.5 billion topping the list. Another case in which a corporation is demanding $16 billion, TC v. USA, for the cancelation of the controversial Keystone pipeline by the Biden's administration, is not included in the table below because it has not yet been registered at ICSID. (Source: ICSID and UNCTAD)

In their lawsuits, corporations most often cite protections in FTAs and BITs against "indirect expropriation." This is interpreted to mean regulations and other government actions that reduce the value of an investment. Hence, corporations can sue governments over the enforcement of environmental, health, and other public interest laws or measures arising from democratic or judicial processes. While investment tribunals cannot force a government to repeal laws and regulations, time-consuming, costly litigation and the threat of massive awards for damages often put a "chilling effect" on responsible policy-making.

There has been some movement in recent years to roll back these excessive corporate powers. The European Court of Justice, for example, has ruled that European Union energy companies will not be able to use the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) to sue EU governments. The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement that replaced NAFTA eliminates ISDS between Canada and the United States.

But for the most part, international agreements that allow corporations headquartered in rich countries to continue to wield this weapon against development country governments remain in force, reinforcing neo-colonial North-South relations.

The imbalance of who uses the system the most is already very stark. Most extractive companies that have used ISDS are from countries in Western Europe or the United States, Canada, or Australia. By contrast, countries in the regions of the Global South are the most sued.

A majority of extractives-related ISDS cases have been brought by companies headquartered in just five countries. The United States alone is home to companies that have filed 53 out of the 194 total oil, mining, and gas cases.

The Institute for Policy Studies report Extraction Casino notes that for transnational extractive industries that pollute the planet and contribute to climate change, ISDS is "yet another opportunity to strike it rich through reckless, casino-style gambling, given the recourse they have to bring suits within a system in which the deck is heavily stacked in their favor, and produce a chilling effect on regulations and policies that address climate change."

To effectively combat climate change, governments around the world will need the flexibility to pursue a wide range of actions--without the threat of provoking expensive corporate lawsuits. The ISDS system should not stand in the way of responsible policies to address this existential global threat.

The elimination of the ISDS system should be on the table in Glasgow. At a minimum, negotiators should agree to independent audits of international investment treaties that include ISDS clauses, with meaningful public participation. On the basis of these audits, these agreements should either be cancelled or rewritten in terms that put people's rights and the environment first.