SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

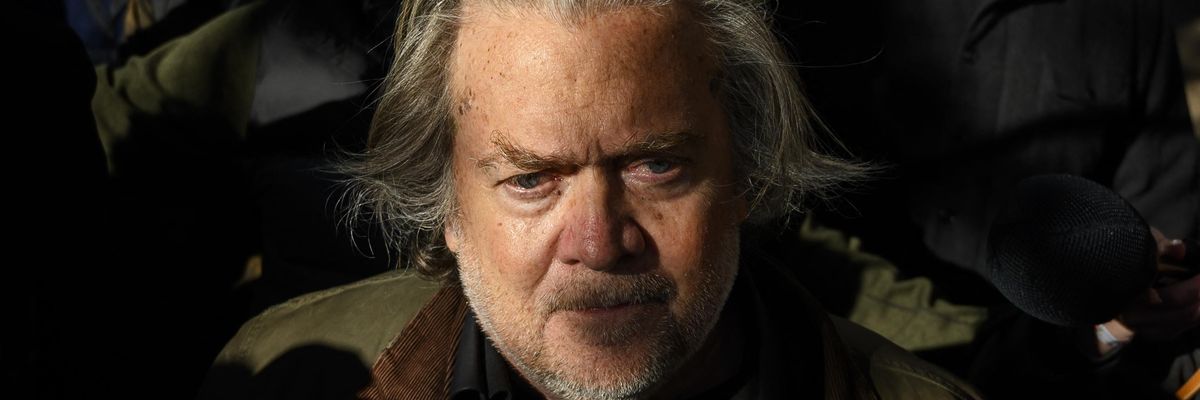

Former Trump Administration White House advisor Steve Bannon leaves after an appearance in the Federal District Court in Washington, DC on November 15, 2021. - A defiant Steve Bannon, former president Donald Trump's long-time advisor, turned himself into the FBI Monday to face charges of contempt of Congress after refusing to testify on the January 6 Capitol assault. (Photo: Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images)

Yale historian Timothy's Snyder'sBlack Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning was published in 2015. It was a book on a subject that had already received vast attention from historians, but it stood out for its novel thesis: it was traditional bureaucratic state structures which protected persons under their aegis. This applied even during the Holocaust. It was the destruction of the state apparatus or the stripping of persons' citizenship that made the worst horrors possible.

It received mostly positive reviews but some experts considered the thesis too pointed, and dismissed as far-fetched the final chapter's scenarios that major nations might react to future crises by repeating the horrors of the 1940's. Richard J. Evans, a respected authority on the period, wrote, "[Snyder's] speculations about possible Chinese or Russian wars of conquest driven by the need for resources are wild in the extreme."

Once you begin that deconstruction, where does it end?

But in both politics and history, six years are an eternity. Having endured a four-year sample of authoritarian government, a violent and nearly successful coup d'etat, and a pandemic that has engendered a global sense of intractable crisis, it is fitting to consider whether Snyder was an alarmist or his critics complacent.

Contrary to the common belief that highly organized and disciplined state institutions, extensively armed with laws, rules, and bureaucratic procedures, constitute the greatest threat to life and liberty (the belief of virtually every libertarian conservative since Friedrich Hayek in the 1940s), Snyder believes that it is precisely the breakdown - or deliberate smashing - of such structures that bring the most horrific results.

The Holocaust originated in Adolf Hitler's notion of creating a vast "living space" in Eastern Europe for German colonial settlement and the exploitation of resources like grain and oil. This entailed the annihilation of all Jews and the enslavement of much of the rest of the resident population. Regardless of prewar ideological theorizing, the horrific realization of it unfolded according to no detailed tactical plan other than the demolishing of the states existing there, the destruction of intermediary civil-society institutions, and stirring up local collaborationists, criminals and opportunists to engage in pogroms and denunciations.

The fact that there were no detailed orders from on high (other than general directives shrouded in euphemism, something that has fueled the Holocaust denial industry for decades) was highly significant. Groups like the SS didn't need a blueprint: they engaged in self-directed, "entrepreneurial" violence, seeing what provoked the local population to join in, what got results, and what didn't.

Snyder shows that where states were destroyed and institutions obliterated, the results were almost invariably lethal for the vulnerable, as in Poland and the Baltics. By contrast, in countries like Denmark, where the prewar state structure remained largely intact, almost all Jews survived. France, maintaining the semblance of a sovereign French state in the southern half, lay somewhere in the middle of the spectrum.

Even Hungary, which was becoming a charnel house for its Jewish inhabitants by 1944, saw thousands of Jews saved through the intervention of a state institution--in the person of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who issued passports giving them protection as Swedish subjects, and housed them in dozens of buildings he declared extraterritorial.

Timothy Snyder's message is clear: the stodgy institution of the traditional state, whose slow, cumbersome, and supposedly oppressive bureaucracy is the stuff of jokes, handwringing, and resentment, is in extremis the only thing between the lone individual and anyone stronger or better armed who wishes to kill him. The state, as it has evolved with its chanceries, ministries, departments, and courts, creates a skein of rules and procedures that can impede the unscrupulous and the murderous. Do away with it, and the result is likelier to be Somalia than the utopian fever-dreams of libertarians.

Am I drawing too grim a conclusion in thinking that former Donald Trump adviser (and admirer of European fascism) Steven Bannon's statement about "deconstructing the administrative state" leads in the cataclysmic direction Snyder describes rather than what the CATO Institute would have us believe? The Washington Posthas interpreted Bannon's phrase to mean "getting rid of the system of taxes, regulations and trade pacts that the president says have stymied economic growth and infringed upon U.S. sovereignty."

Once you begin that deconstruction, where does it end? People may be tempted to think, as with The Washington Post, that it involves slashing taxes and spending. Today's Republicans would also gladly get rid of food inspection, drug trials, consumer and worker safety codes, and pollution controls. That's bad enough for most of us, but it could also lead, as Snyder has said, to "a new kind of politics" predicated on the destruction of the state as upholder of law, normal parliamentary politics, and civilized social relations.

A key aspect of Nazi Germany was the creation of parallel or hybrid organizations like the SS, not a part of the normal state structure per se but acting in the state's name without being bound by the traditional rules of a civil service or the uniform code of an official military. Eventually, they began to supplant the state organs. In practice, totalitarian societies (like the USSR or Maoist China) typically develop such parallel or hybrid organizations, with party groups holding the real power as against the formal state structure.

In the last few years, we saw the beginnings of such structures in the Trump administration. Militias, Oath Keepers, self-appointed poll watchers, and impromptu insurrectionists comprised the leading edge of parallel organizations, not part of the state structure but obedient to the supreme leader and shielded by him from accountability. In some respects they were also hybrid organizations, given the number of police officers and military personnel identified in the January 6th assault on the seat of government.

We are starting to see "entrepreneurship in violence" and ominous threats that cause election officials and school administrators to quit. We note that members of Congress, federal officials in a co-equal branch of government, have been advised not to hold town meetings because it is too dangerous. Do these acts both delegitimize the state by showing its inability to maintain a monopoly on coercion, as well as provide do-it-yourself training in and psychological conditioning for potentially greater acts of violence in the future?

That is exactly how Nazi storm troopers paved the way for Hitler's assumption of power, by winning the streets through violent clashes and threats, by assassinating rival politicians, and by convincing large portions of the German public that the Weimar Republic was illegitimate because it couldn't maintain order.

We saw the beginnings of non-state entrepreneurship in areas other than street thuggery as well. While many presidents have had an informal kitchen cabinet, Trump literally had no governmental process for establishing policy. Instead, Fox News (i.e., Sean Hannity and his cohorts) acted both as a policy formulation shop and ministry of propaganda. Not being able to rely on the State Department to extort the government of Ukraine, Trump relied on personal hangers-on like Rudy Giuliani to tell the Ukrainians what was demanded of them.

Does the supreme leader's pardoning of obviously guilty and uncontrite persons for crimes committed on his behalf make a mockery of the rule of law, the foremost principle in a humane state? Does he issue a few ambiguous statements supporting lawless groups, allowing them to "work towards the Fuhrer" as in Charlottesville or on January 6th while maintaining a degree of deniability, just as Germany's leaders claimed they knew nothing at the Nuremberg tribunal?

Trump may have been to all appearances the laziest US president in history, spending as little time in the capital as he could get away with, preferring to lounge with his adoring cronies at Mar-a-Lago. Where have we seen this before?

Albert Speer's memoirs attest to frequent impromptu trips by Hitler and his retinue to his mountain aerie, the Berghof, to escape the paperwork in Berlin. His governmental administration was chaotic, and he frequently pitted subordinate structures or individuals against each other on the divide-and-rule principle (Army versus SS, Himmler versus Goring).

This was a management principle of Trump's throughout his career. In both cases, the leader is exalted above the mundane task of management: he issues broad directives - or hints - as to what he wants and followers use their initiative. Contrary to what we might think about tightly organized totalitarianism, the populist-charismatic dictatorship is a kind of "organized chaos" responding to the ever-changing whims of the supreme leader.

Hitler and his minions were motivated by the most fantastic conspiracy theories, and America is now saturated with outlandish beliefs that "explain" every aspect of life, from medicine to climate science to "elites," to minorities, to foreigners. We now have a sitting member of Congress, Marjorie Taylor Greene, who believes that Jewish space lasers caused the wildfires in California. To judge from their votes on conducting an investigation, a majority of her Republican colleagues think the January 6th assault on the very building in which they were assembled never actually happened.

There is method to the madness of these psychotic conspiracy theories, which are common to all authoritarian movements. In concert with the physical destruction of the traditional state, the theories are designed to deconstruct normal politics and render them absurd and impossible to sustain. In an atmosphere choked with lies and rumors, America becomes Russia, where "nothing is true and everything is possible." The zealots are kept at a fever pitch, while the sane citizens give up in despair and disgust, trying their best to maintain a decent private space away from public life.

Of course, Snyder's thesis is not applicable to every authoritarian government or to every breakdown of order. No historical comparison between different eras can be considered scientific proof that they are identical. But when points of correspondence pile up and behavioral patterns appear weirdly similar, warning bells should ring.

History is an open system, not subject to prediction in the manner of lunar eclipses or Halley's Comet. But it is fair to say that the recent toxic politics across the world, immensely exacerbated by a global pandemic taking five million lives, has delivered a shock at least as profound as the Great Depression that began in 1929. It is hardly alarmist speculation to wonder if the future consequences could be as dire.

If we consider the present world situation, things are dire enough. For years, Vladimir Putin has spoken of Ukraine as "not really a state" in the same manner as Hitler claimed that Poland had no right to a sovereign existence. The Russian leader put his belief into practice with the formal annexation of Crimea and the de facto incorporation of large areas of the Donbas. There are oil deposits off the shores of the former and industrial and mineral assets in the latter.

China has encouraged its ethnic Han minority to settle in Xinjiang and displace the Uyghurs living there. Meanwhile, Beijing has suppressed the local Uyghur culture, imprisoned a large percentage of them, and engaged in other acts that according to the United Nations would constitute genocide.

China also has unilaterally enlarged its territorial waters in the South China Sea by over one million square miles. It may serve both as an exclusive fishing area to ensure a protein supply (the Chinese government is ultra-sensitive to the nation's food security) as well as a secure zone for seabed mining to supply China's voracious industries.

Lest the United States moralize about other countries' misdeeds, Timothy Snyder reminds us of our own misadventure in aggression and state destruction. The 2003 invasion of Iraq was predicated on utterly smashing the Baathist state apparatus. The results were untold misery in the region, the rise of ISIS, and a blowback into US domestic politics that may well have helped fuel the rise of Trump and his gang.

One final irony of history: as was painfully obvious to many of us at the time, the Iraq invasion was enthusiastically supported by many American dispensationalist evangelicals on the theory that a war in the Middle East would bring on the second coming of Christ.

Snyder notes that the August 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact was met outside of Germany and the USSR with almost universal horror and foreboding - and correctly so, for it made the most terrible war in history inevitable. He says there was one curious exception: American dispensationalist evangelicals hailed the Hitler-Stalin pact, with all the destruction of people and states that it foretold, as a sign of the coming Armageddon that would trigger that second coming of Christ.

In 2021, dispensationalists remain among the staunchest supporters of Donald Trump. They thirst for his return to power as a secular enactment of Christ's return to earth. How many warnings do we need, and what will shake the complacency of those who now hold a tenuous grip on political power?

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Yale historian Timothy's Snyder'sBlack Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning was published in 2015. It was a book on a subject that had already received vast attention from historians, but it stood out for its novel thesis: it was traditional bureaucratic state structures which protected persons under their aegis. This applied even during the Holocaust. It was the destruction of the state apparatus or the stripping of persons' citizenship that made the worst horrors possible.

It received mostly positive reviews but some experts considered the thesis too pointed, and dismissed as far-fetched the final chapter's scenarios that major nations might react to future crises by repeating the horrors of the 1940's. Richard J. Evans, a respected authority on the period, wrote, "[Snyder's] speculations about possible Chinese or Russian wars of conquest driven by the need for resources are wild in the extreme."

Once you begin that deconstruction, where does it end?

But in both politics and history, six years are an eternity. Having endured a four-year sample of authoritarian government, a violent and nearly successful coup d'etat, and a pandemic that has engendered a global sense of intractable crisis, it is fitting to consider whether Snyder was an alarmist or his critics complacent.

Contrary to the common belief that highly organized and disciplined state institutions, extensively armed with laws, rules, and bureaucratic procedures, constitute the greatest threat to life and liberty (the belief of virtually every libertarian conservative since Friedrich Hayek in the 1940s), Snyder believes that it is precisely the breakdown - or deliberate smashing - of such structures that bring the most horrific results.

The Holocaust originated in Adolf Hitler's notion of creating a vast "living space" in Eastern Europe for German colonial settlement and the exploitation of resources like grain and oil. This entailed the annihilation of all Jews and the enslavement of much of the rest of the resident population. Regardless of prewar ideological theorizing, the horrific realization of it unfolded according to no detailed tactical plan other than the demolishing of the states existing there, the destruction of intermediary civil-society institutions, and stirring up local collaborationists, criminals and opportunists to engage in pogroms and denunciations.

The fact that there were no detailed orders from on high (other than general directives shrouded in euphemism, something that has fueled the Holocaust denial industry for decades) was highly significant. Groups like the SS didn't need a blueprint: they engaged in self-directed, "entrepreneurial" violence, seeing what provoked the local population to join in, what got results, and what didn't.

Snyder shows that where states were destroyed and institutions obliterated, the results were almost invariably lethal for the vulnerable, as in Poland and the Baltics. By contrast, in countries like Denmark, where the prewar state structure remained largely intact, almost all Jews survived. France, maintaining the semblance of a sovereign French state in the southern half, lay somewhere in the middle of the spectrum.

Even Hungary, which was becoming a charnel house for its Jewish inhabitants by 1944, saw thousands of Jews saved through the intervention of a state institution--in the person of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who issued passports giving them protection as Swedish subjects, and housed them in dozens of buildings he declared extraterritorial.

Timothy Snyder's message is clear: the stodgy institution of the traditional state, whose slow, cumbersome, and supposedly oppressive bureaucracy is the stuff of jokes, handwringing, and resentment, is in extremis the only thing between the lone individual and anyone stronger or better armed who wishes to kill him. The state, as it has evolved with its chanceries, ministries, departments, and courts, creates a skein of rules and procedures that can impede the unscrupulous and the murderous. Do away with it, and the result is likelier to be Somalia than the utopian fever-dreams of libertarians.

Am I drawing too grim a conclusion in thinking that former Donald Trump adviser (and admirer of European fascism) Steven Bannon's statement about "deconstructing the administrative state" leads in the cataclysmic direction Snyder describes rather than what the CATO Institute would have us believe? The Washington Posthas interpreted Bannon's phrase to mean "getting rid of the system of taxes, regulations and trade pacts that the president says have stymied economic growth and infringed upon U.S. sovereignty."

Once you begin that deconstruction, where does it end? People may be tempted to think, as with The Washington Post, that it involves slashing taxes and spending. Today's Republicans would also gladly get rid of food inspection, drug trials, consumer and worker safety codes, and pollution controls. That's bad enough for most of us, but it could also lead, as Snyder has said, to "a new kind of politics" predicated on the destruction of the state as upholder of law, normal parliamentary politics, and civilized social relations.

A key aspect of Nazi Germany was the creation of parallel or hybrid organizations like the SS, not a part of the normal state structure per se but acting in the state's name without being bound by the traditional rules of a civil service or the uniform code of an official military. Eventually, they began to supplant the state organs. In practice, totalitarian societies (like the USSR or Maoist China) typically develop such parallel or hybrid organizations, with party groups holding the real power as against the formal state structure.

In the last few years, we saw the beginnings of such structures in the Trump administration. Militias, Oath Keepers, self-appointed poll watchers, and impromptu insurrectionists comprised the leading edge of parallel organizations, not part of the state structure but obedient to the supreme leader and shielded by him from accountability. In some respects they were also hybrid organizations, given the number of police officers and military personnel identified in the January 6th assault on the seat of government.

We are starting to see "entrepreneurship in violence" and ominous threats that cause election officials and school administrators to quit. We note that members of Congress, federal officials in a co-equal branch of government, have been advised not to hold town meetings because it is too dangerous. Do these acts both delegitimize the state by showing its inability to maintain a monopoly on coercion, as well as provide do-it-yourself training in and psychological conditioning for potentially greater acts of violence in the future?

That is exactly how Nazi storm troopers paved the way for Hitler's assumption of power, by winning the streets through violent clashes and threats, by assassinating rival politicians, and by convincing large portions of the German public that the Weimar Republic was illegitimate because it couldn't maintain order.

We saw the beginnings of non-state entrepreneurship in areas other than street thuggery as well. While many presidents have had an informal kitchen cabinet, Trump literally had no governmental process for establishing policy. Instead, Fox News (i.e., Sean Hannity and his cohorts) acted both as a policy formulation shop and ministry of propaganda. Not being able to rely on the State Department to extort the government of Ukraine, Trump relied on personal hangers-on like Rudy Giuliani to tell the Ukrainians what was demanded of them.

Does the supreme leader's pardoning of obviously guilty and uncontrite persons for crimes committed on his behalf make a mockery of the rule of law, the foremost principle in a humane state? Does he issue a few ambiguous statements supporting lawless groups, allowing them to "work towards the Fuhrer" as in Charlottesville or on January 6th while maintaining a degree of deniability, just as Germany's leaders claimed they knew nothing at the Nuremberg tribunal?

Trump may have been to all appearances the laziest US president in history, spending as little time in the capital as he could get away with, preferring to lounge with his adoring cronies at Mar-a-Lago. Where have we seen this before?

Albert Speer's memoirs attest to frequent impromptu trips by Hitler and his retinue to his mountain aerie, the Berghof, to escape the paperwork in Berlin. His governmental administration was chaotic, and he frequently pitted subordinate structures or individuals against each other on the divide-and-rule principle (Army versus SS, Himmler versus Goring).

This was a management principle of Trump's throughout his career. In both cases, the leader is exalted above the mundane task of management: he issues broad directives - or hints - as to what he wants and followers use their initiative. Contrary to what we might think about tightly organized totalitarianism, the populist-charismatic dictatorship is a kind of "organized chaos" responding to the ever-changing whims of the supreme leader.

Hitler and his minions were motivated by the most fantastic conspiracy theories, and America is now saturated with outlandish beliefs that "explain" every aspect of life, from medicine to climate science to "elites," to minorities, to foreigners. We now have a sitting member of Congress, Marjorie Taylor Greene, who believes that Jewish space lasers caused the wildfires in California. To judge from their votes on conducting an investigation, a majority of her Republican colleagues think the January 6th assault on the very building in which they were assembled never actually happened.

There is method to the madness of these psychotic conspiracy theories, which are common to all authoritarian movements. In concert with the physical destruction of the traditional state, the theories are designed to deconstruct normal politics and render them absurd and impossible to sustain. In an atmosphere choked with lies and rumors, America becomes Russia, where "nothing is true and everything is possible." The zealots are kept at a fever pitch, while the sane citizens give up in despair and disgust, trying their best to maintain a decent private space away from public life.

Of course, Snyder's thesis is not applicable to every authoritarian government or to every breakdown of order. No historical comparison between different eras can be considered scientific proof that they are identical. But when points of correspondence pile up and behavioral patterns appear weirdly similar, warning bells should ring.

History is an open system, not subject to prediction in the manner of lunar eclipses or Halley's Comet. But it is fair to say that the recent toxic politics across the world, immensely exacerbated by a global pandemic taking five million lives, has delivered a shock at least as profound as the Great Depression that began in 1929. It is hardly alarmist speculation to wonder if the future consequences could be as dire.

If we consider the present world situation, things are dire enough. For years, Vladimir Putin has spoken of Ukraine as "not really a state" in the same manner as Hitler claimed that Poland had no right to a sovereign existence. The Russian leader put his belief into practice with the formal annexation of Crimea and the de facto incorporation of large areas of the Donbas. There are oil deposits off the shores of the former and industrial and mineral assets in the latter.

China has encouraged its ethnic Han minority to settle in Xinjiang and displace the Uyghurs living there. Meanwhile, Beijing has suppressed the local Uyghur culture, imprisoned a large percentage of them, and engaged in other acts that according to the United Nations would constitute genocide.

China also has unilaterally enlarged its territorial waters in the South China Sea by over one million square miles. It may serve both as an exclusive fishing area to ensure a protein supply (the Chinese government is ultra-sensitive to the nation's food security) as well as a secure zone for seabed mining to supply China's voracious industries.

Lest the United States moralize about other countries' misdeeds, Timothy Snyder reminds us of our own misadventure in aggression and state destruction. The 2003 invasion of Iraq was predicated on utterly smashing the Baathist state apparatus. The results were untold misery in the region, the rise of ISIS, and a blowback into US domestic politics that may well have helped fuel the rise of Trump and his gang.

One final irony of history: as was painfully obvious to many of us at the time, the Iraq invasion was enthusiastically supported by many American dispensationalist evangelicals on the theory that a war in the Middle East would bring on the second coming of Christ.

Snyder notes that the August 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact was met outside of Germany and the USSR with almost universal horror and foreboding - and correctly so, for it made the most terrible war in history inevitable. He says there was one curious exception: American dispensationalist evangelicals hailed the Hitler-Stalin pact, with all the destruction of people and states that it foretold, as a sign of the coming Armageddon that would trigger that second coming of Christ.

In 2021, dispensationalists remain among the staunchest supporters of Donald Trump. They thirst for his return to power as a secular enactment of Christ's return to earth. How many warnings do we need, and what will shake the complacency of those who now hold a tenuous grip on political power?

Yale historian Timothy's Snyder'sBlack Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning was published in 2015. It was a book on a subject that had already received vast attention from historians, but it stood out for its novel thesis: it was traditional bureaucratic state structures which protected persons under their aegis. This applied even during the Holocaust. It was the destruction of the state apparatus or the stripping of persons' citizenship that made the worst horrors possible.

It received mostly positive reviews but some experts considered the thesis too pointed, and dismissed as far-fetched the final chapter's scenarios that major nations might react to future crises by repeating the horrors of the 1940's. Richard J. Evans, a respected authority on the period, wrote, "[Snyder's] speculations about possible Chinese or Russian wars of conquest driven by the need for resources are wild in the extreme."

Once you begin that deconstruction, where does it end?

But in both politics and history, six years are an eternity. Having endured a four-year sample of authoritarian government, a violent and nearly successful coup d'etat, and a pandemic that has engendered a global sense of intractable crisis, it is fitting to consider whether Snyder was an alarmist or his critics complacent.

Contrary to the common belief that highly organized and disciplined state institutions, extensively armed with laws, rules, and bureaucratic procedures, constitute the greatest threat to life and liberty (the belief of virtually every libertarian conservative since Friedrich Hayek in the 1940s), Snyder believes that it is precisely the breakdown - or deliberate smashing - of such structures that bring the most horrific results.

The Holocaust originated in Adolf Hitler's notion of creating a vast "living space" in Eastern Europe for German colonial settlement and the exploitation of resources like grain and oil. This entailed the annihilation of all Jews and the enslavement of much of the rest of the resident population. Regardless of prewar ideological theorizing, the horrific realization of it unfolded according to no detailed tactical plan other than the demolishing of the states existing there, the destruction of intermediary civil-society institutions, and stirring up local collaborationists, criminals and opportunists to engage in pogroms and denunciations.

The fact that there were no detailed orders from on high (other than general directives shrouded in euphemism, something that has fueled the Holocaust denial industry for decades) was highly significant. Groups like the SS didn't need a blueprint: they engaged in self-directed, "entrepreneurial" violence, seeing what provoked the local population to join in, what got results, and what didn't.

Snyder shows that where states were destroyed and institutions obliterated, the results were almost invariably lethal for the vulnerable, as in Poland and the Baltics. By contrast, in countries like Denmark, where the prewar state structure remained largely intact, almost all Jews survived. France, maintaining the semblance of a sovereign French state in the southern half, lay somewhere in the middle of the spectrum.

Even Hungary, which was becoming a charnel house for its Jewish inhabitants by 1944, saw thousands of Jews saved through the intervention of a state institution--in the person of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who issued passports giving them protection as Swedish subjects, and housed them in dozens of buildings he declared extraterritorial.

Timothy Snyder's message is clear: the stodgy institution of the traditional state, whose slow, cumbersome, and supposedly oppressive bureaucracy is the stuff of jokes, handwringing, and resentment, is in extremis the only thing between the lone individual and anyone stronger or better armed who wishes to kill him. The state, as it has evolved with its chanceries, ministries, departments, and courts, creates a skein of rules and procedures that can impede the unscrupulous and the murderous. Do away with it, and the result is likelier to be Somalia than the utopian fever-dreams of libertarians.

Am I drawing too grim a conclusion in thinking that former Donald Trump adviser (and admirer of European fascism) Steven Bannon's statement about "deconstructing the administrative state" leads in the cataclysmic direction Snyder describes rather than what the CATO Institute would have us believe? The Washington Posthas interpreted Bannon's phrase to mean "getting rid of the system of taxes, regulations and trade pacts that the president says have stymied economic growth and infringed upon U.S. sovereignty."

Once you begin that deconstruction, where does it end? People may be tempted to think, as with The Washington Post, that it involves slashing taxes and spending. Today's Republicans would also gladly get rid of food inspection, drug trials, consumer and worker safety codes, and pollution controls. That's bad enough for most of us, but it could also lead, as Snyder has said, to "a new kind of politics" predicated on the destruction of the state as upholder of law, normal parliamentary politics, and civilized social relations.

A key aspect of Nazi Germany was the creation of parallel or hybrid organizations like the SS, not a part of the normal state structure per se but acting in the state's name without being bound by the traditional rules of a civil service or the uniform code of an official military. Eventually, they began to supplant the state organs. In practice, totalitarian societies (like the USSR or Maoist China) typically develop such parallel or hybrid organizations, with party groups holding the real power as against the formal state structure.

In the last few years, we saw the beginnings of such structures in the Trump administration. Militias, Oath Keepers, self-appointed poll watchers, and impromptu insurrectionists comprised the leading edge of parallel organizations, not part of the state structure but obedient to the supreme leader and shielded by him from accountability. In some respects they were also hybrid organizations, given the number of police officers and military personnel identified in the January 6th assault on the seat of government.

We are starting to see "entrepreneurship in violence" and ominous threats that cause election officials and school administrators to quit. We note that members of Congress, federal officials in a co-equal branch of government, have been advised not to hold town meetings because it is too dangerous. Do these acts both delegitimize the state by showing its inability to maintain a monopoly on coercion, as well as provide do-it-yourself training in and psychological conditioning for potentially greater acts of violence in the future?

That is exactly how Nazi storm troopers paved the way for Hitler's assumption of power, by winning the streets through violent clashes and threats, by assassinating rival politicians, and by convincing large portions of the German public that the Weimar Republic was illegitimate because it couldn't maintain order.

We saw the beginnings of non-state entrepreneurship in areas other than street thuggery as well. While many presidents have had an informal kitchen cabinet, Trump literally had no governmental process for establishing policy. Instead, Fox News (i.e., Sean Hannity and his cohorts) acted both as a policy formulation shop and ministry of propaganda. Not being able to rely on the State Department to extort the government of Ukraine, Trump relied on personal hangers-on like Rudy Giuliani to tell the Ukrainians what was demanded of them.

Does the supreme leader's pardoning of obviously guilty and uncontrite persons for crimes committed on his behalf make a mockery of the rule of law, the foremost principle in a humane state? Does he issue a few ambiguous statements supporting lawless groups, allowing them to "work towards the Fuhrer" as in Charlottesville or on January 6th while maintaining a degree of deniability, just as Germany's leaders claimed they knew nothing at the Nuremberg tribunal?

Trump may have been to all appearances the laziest US president in history, spending as little time in the capital as he could get away with, preferring to lounge with his adoring cronies at Mar-a-Lago. Where have we seen this before?

Albert Speer's memoirs attest to frequent impromptu trips by Hitler and his retinue to his mountain aerie, the Berghof, to escape the paperwork in Berlin. His governmental administration was chaotic, and he frequently pitted subordinate structures or individuals against each other on the divide-and-rule principle (Army versus SS, Himmler versus Goring).

This was a management principle of Trump's throughout his career. In both cases, the leader is exalted above the mundane task of management: he issues broad directives - or hints - as to what he wants and followers use their initiative. Contrary to what we might think about tightly organized totalitarianism, the populist-charismatic dictatorship is a kind of "organized chaos" responding to the ever-changing whims of the supreme leader.

Hitler and his minions were motivated by the most fantastic conspiracy theories, and America is now saturated with outlandish beliefs that "explain" every aspect of life, from medicine to climate science to "elites," to minorities, to foreigners. We now have a sitting member of Congress, Marjorie Taylor Greene, who believes that Jewish space lasers caused the wildfires in California. To judge from their votes on conducting an investigation, a majority of her Republican colleagues think the January 6th assault on the very building in which they were assembled never actually happened.

There is method to the madness of these psychotic conspiracy theories, which are common to all authoritarian movements. In concert with the physical destruction of the traditional state, the theories are designed to deconstruct normal politics and render them absurd and impossible to sustain. In an atmosphere choked with lies and rumors, America becomes Russia, where "nothing is true and everything is possible." The zealots are kept at a fever pitch, while the sane citizens give up in despair and disgust, trying their best to maintain a decent private space away from public life.

Of course, Snyder's thesis is not applicable to every authoritarian government or to every breakdown of order. No historical comparison between different eras can be considered scientific proof that they are identical. But when points of correspondence pile up and behavioral patterns appear weirdly similar, warning bells should ring.

History is an open system, not subject to prediction in the manner of lunar eclipses or Halley's Comet. But it is fair to say that the recent toxic politics across the world, immensely exacerbated by a global pandemic taking five million lives, has delivered a shock at least as profound as the Great Depression that began in 1929. It is hardly alarmist speculation to wonder if the future consequences could be as dire.

If we consider the present world situation, things are dire enough. For years, Vladimir Putin has spoken of Ukraine as "not really a state" in the same manner as Hitler claimed that Poland had no right to a sovereign existence. The Russian leader put his belief into practice with the formal annexation of Crimea and the de facto incorporation of large areas of the Donbas. There are oil deposits off the shores of the former and industrial and mineral assets in the latter.

China has encouraged its ethnic Han minority to settle in Xinjiang and displace the Uyghurs living there. Meanwhile, Beijing has suppressed the local Uyghur culture, imprisoned a large percentage of them, and engaged in other acts that according to the United Nations would constitute genocide.

China also has unilaterally enlarged its territorial waters in the South China Sea by over one million square miles. It may serve both as an exclusive fishing area to ensure a protein supply (the Chinese government is ultra-sensitive to the nation's food security) as well as a secure zone for seabed mining to supply China's voracious industries.

Lest the United States moralize about other countries' misdeeds, Timothy Snyder reminds us of our own misadventure in aggression and state destruction. The 2003 invasion of Iraq was predicated on utterly smashing the Baathist state apparatus. The results were untold misery in the region, the rise of ISIS, and a blowback into US domestic politics that may well have helped fuel the rise of Trump and his gang.

One final irony of history: as was painfully obvious to many of us at the time, the Iraq invasion was enthusiastically supported by many American dispensationalist evangelicals on the theory that a war in the Middle East would bring on the second coming of Christ.

Snyder notes that the August 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact was met outside of Germany and the USSR with almost universal horror and foreboding - and correctly so, for it made the most terrible war in history inevitable. He says there was one curious exception: American dispensationalist evangelicals hailed the Hitler-Stalin pact, with all the destruction of people and states that it foretold, as a sign of the coming Armageddon that would trigger that second coming of Christ.

In 2021, dispensationalists remain among the staunchest supporters of Donald Trump. They thirst for his return to power as a secular enactment of Christ's return to earth. How many warnings do we need, and what will shake the complacency of those who now hold a tenuous grip on political power?