SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Protesters move through restricted Blue Zone area of COP26 climate summit on November 12, 2021 in Glasgow, Scotland. As World Leaders meet to discuss climate change at the COP26 Summit, many climate action groups have taken to the streets to protest for real progress to be made by governments to reduce carbon emissions, clean up the oceans, reduce fossil fuel use and other issues relating to global heating. (Photo: Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images)

If it wasn't for the greenhouse effect, the Earth would be as cold and dead as the far side of the moon.

The pulses of energy released by the sun's gravity smashing together hydrogen nuclei and fusing them into helium atoms have to travel the same 150 million kilometres to get to both the Earth and the moon. They arrive at each as the same mix of ultraviolet, infrared and visible light. At both, they heat up rocks, which aren't so dissimilar, which absorb that energy and emit it as warm, infrared radiation, with luxurious, long wavelengths.

But from the moon, this warmth slips freely back into space. On Earth, it has to navigate an atmosphere.

Oxygen and nitrogen particles, which make up 99.03% of our air, are tiny things, even by molecular standards. Just as thickets of grass don't trip up ambling giraffes, these gases don't interfere with reflected heat waves, which can straddle as much as a millimetre. Nor, for that matter, does argon, which makes up another 0.93%.

But around 0.04% of Earth's atmosphere is CO2; 0.00018% is methane (CH4); 0.00006% is ozone (O3) and 0.00003% is nitrogen oxide (NO2). These molecules are all bigger and more complex. They can bend and stretch and twist in a number of directions. And so, like a spindly hedge, they catch infrared radiation reflected by the Earth and bounce it back towards the planet. They do it with such astonishing power that those tiny quantities ensure that Earth isn't a cold, hard rock like the dark side of the moon, where the average temperature is -153degC. We have a warm, breathing and bountiful planet.

The potency of these gases is what makes them dangerous. When humans first set foot on the moon, CO2 made up only 0.03% of our air. The concentration of methane in the atmosphere has more than doubled since preindustrial times. Over the past 800,000 years--more than twice as long as homo sapiens has existed--concentrations of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere rarely exceeded 280 parts per billion (ppb). With the development of industrial agriculture over the past century, they've increased to 331ppb.

In theory, world leaders have been in Glasgow over the past fortnight to negotiate how to reduce emissions of these astonishingly potent gases. In reality, most seemed more interested in building soft power and blaming someone else. But what they don't seem to understand is that however much human power they accrue, it will be nothing next to the might of CO2, CH4, NO2 and O3, with their firm, covalent bonds forming a tight blanket around the only home we've ever known.

I've followed the annual cycle of UN climate negotiations for most of my life. This year, the conference, COP26, came to my home country, Scotland. For the past two weeks, I've been surrounded by climate activists from across the planet, old friends and new, thinking and gossiping and analysing together. And despite the shortcomings of the official conference itself, I was struck by how remarkably positive they felt.

The final text agreed in Glasgow is a pitiful prayer, begging for the forgiveness of these celestial compounds. It expresses "alarm and concern", pointing passively at the burning building and suggesting someone do something. It "stresses the urgency of increased ambition and action". But it is neither ambitious nor details any sprightly action.

It "notes with serious concern that the current provision of climate finance for adaptation is insufficient to respond to worsening climate change impacts in developing countr[ies]," and "notes with regret" that the promise of rich countries "to mobilize jointly $100bn per year by 2020" to help poorer countries cope with the climate crisis "has not yet been met". I remember a landlord I had once noting that, with regret, he was increasing my rent.

It "recognizes that limiting global warming to 1.5degC by 2100 requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions" and "invites" governments "to consider further opportunities" to reduce emissions. It "calls upon" them to "accelerate efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies" as though this wasn't a document drafted by those very governments; as though phasing out all subsidies for fossil fuels wasn't what we needed to do a generation ago. What we must do in the coming years is stop burning them entirely.

There's not much reason to believe the governments that signed the COP26 draft will take action.

Funding for loss and damage done by climate change caused by the rich to the lives and infrastructure of the impoverished was blocked by the UK, EU and US. The Global Methane Pledge, an initiative announced by the EU and the US at the start of COP26, is largely about making leaky fossil fuel infrastructure more efficient--the lowest of low-hanging fruits. The pledge by some countries to end deforestation by 2030 has left many Indigenous activists who live in those forests with rolling eyes, and the new voluntary nationally determined contributions don't add up to enough to prevent 1.5degC of warming.

In any case, there's not much reason to believe the governments that signed the draft will take action. The world banned torture in 1987, but most states signed the convention, then ignored it.

None of this should surprise us. After all, the conference was built atop a crumbling neoliberal world order. Even its stated aim--to find ways to reach 'net zero' by the middle of the century--is dubious.

"This term is being used to cover up a multitude of sins. Because when people are talking about net zero, they're essentially talking about offsetting," said Nick Dearden, director of the non-governmental organisation, Global Justice Now, when chatting with me in a cafe on the Broomielaw, once the heart of Glasgow's shipbuilding district.

Of the conference's climate finance deal, which was agreed last Tuesday under the gavel of "rockstar central banker" and, if rumours are to be believed, wannabe Canadian prime minister Mark Carney, Dearden added: "A lot of this finance package is about net zero in that sense--offsetting emissions, which doesn't necessarily mean reducing your emissions at all."

It could mean increasing your emissions, while paying to 'offset' them with something else "which may or may not be useful," or even worse, offsetting them "with the vague notion that some as yet unidentified technology might help us to reduce these emissions," he said.

Perhaps most importantly, the 'net' in net zero often represents false accounting: you can't plant trees to make up for flights taken by your firm, because we need to both reforest the world and stop flying.

Any cynicism about carbon-trading and notions of 'net zero' is surely confirmed when you look at who is pushing them. The International Emissions Trading Association, which hosted a space at the core of COP26, is a representative body for many of the world's biggest polluters.

"The heart of it is that the government is obsessed with nudging the market," said Dearden. "And, of course, it isn't going to work. The market is going to be completely unable to deal with what's happening.

"Ultimately, you look at the global economy that we've created over the last 40 years, the neoliberal global economy--that's what's driving climate change. And no wonder, because the logic at the heart of that economy is that there is no right more important than the right to make profit.

"The whole economy is geared towards extremely short-term profit maximisation, no matter what the consequences are. And so what that essentially means is that you extract from workers, you extract from the Global South, you extract from the environment, you extract from future generations in order to make a profit today.

"Most of those issues around the global economy were not even on the agenda, not even talked about here at all. I think that goes to the heart of what the problem is. The governments, like the British government, that are really driving the process, want as much as possible to stay the same. They certainly don't want to interfere in rules that were put there in the first place to keep some countries rich, and some people rich and other countries poor.

"We have a global economy which hands monopoly power to massive corporations so they can extract rent from the rest of the world," he said. The World Trade Organization's 1995 Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (known as 'TRIPS') is one example of something that wasn't on the agenda at COP26 but should have been.

"The TRIPS agreement was created by the pharmaceutical industry so that they could exert monopoly power on the rest of the world and profiteer. That's been bad enough when it comes to vaccines and essential medicines. Imagine what that's going to be like when a handful of multinational corporations monopolise the green technologies that we need to run low carbon economies. We need to begin dismantling it, we need to put climate waivers in at least as a minimum, exactly like we're talking about with vaccines."

But these sorts of ideas, he added, are "not even mentioned by anybody ... It's just nowhere in the discussion".

For the British government, COP26 was a chance to take on a starring role in the soap opera of global politics. By that measure, the whole thing was a failure. The hosts won the 'carbon dinosaurs' award on the first day for making the conference what climate activist Greta Thunberg described as the "most excluding COP ever". The waits in lengthy outdoor queues, as winds swept up the River Clyde, were the talk of the first couple of days. As journalist George Monbiot pointed out, Boris Johnson fell asleep in the opening plenary then shot off in a private jet for dinner with a climate sceptic.

The only reason I can think of that the UK government chose Glasgow as a location was in the hope of upstaging Nicola Sturgeon on her own territory, and in that, it clearly failed. Scotland's first minister looked like the true host in her home city. Without a seat at the table, she stood on the stage. This weekend, a Scottish National Party (SNP) activist delivered a leaflet to every house on my street: "Scotland helped lead the world into the industrial age. Now, we're proud to help lead the world into the net-zero age."

If the SNP can rely on its vast membership to deliver its message, then the Tories have to fall back on the official media, which, in the UK, has largely divided into two categories: those that have declared the whole thing a success and those that blame India and China for its failure.

"By focusing only on coal and not including oil and gas, this text would disproportionately impact certain developing countries like China and India. India said in negotiations that all fossil fuels must be phased down, in an equitable manner. This is quite a reasonable response that is supported by a broad coalition of civil society groups which, earlier at COP26, released a report about how this might be done. A globally equitable fossil fuel phase-out is essential for the just, feminist and green transitions that countries need to make.

"But the United States framed this as India trying to block text on fossil fuels ... Knowing that many will not examine the claims critically, the United States is publicly claiming credit for getting fossil fuel language into the text while painting developing countries as the blockers. Meanwhile, of course, the Biden administration refuses to shut down new fossil fuel infrastructure at home."

The biggest change in the economics of fossil fuels over the past decade is that Barack Obama's fracking revolution in the US transformed the world's biggest oil consumer into its biggest producer. And while headlines accurately emphasised that coal is a particularly filthy fuel, they largely ignored how polluting America's new fracking habit is. A NASA study in 2018 found that the process of smashing up the ground to access hard-to-reach reserves often leads to vast leakages of natural gas--and has delivered a surge in methane emissions since 2006.

As Blutus Mbambi, a young climate activist from Zambia, said to me this week, "it is disappointing that only coal was mentioned at the COP26. This gives a free pass to the rich countries who have been extracting and polluting for over a century to continue producing oil and gas."

In this context, it's not surprising that China and India--the world's largest coal producers--wanted a more general phasing out of fossil fuels, whereas the US, which is the world's biggest oil producer, wanted to focus firmly on coal.

Much of the coverage has also separated this last-minute argument in the conference's overtime from ongoing discussions about climate finance. A vast portion of Britain's wealth comes from its plunder of India--and to a lesser extent, China--over centuries. Yet the UK, along with other wealthy countries, is still failing to meet promised funding to help formerly colonised countries like India meet the challenge of the climate crisis. China is, in many ways, taking more actual action to slash its emissions than most Western countries. In this context, attempts by the Western press to blame these countries for the failure of Johnson's COP26 need to be seen as the propaganda they are.

Despite all of that, COP26 filled me with hope. Because politics doesn't happen at big glitzy conferences. It happens in every home and workplace in the world. COPs aren't the wind that drives climate action, they are anemometers helping us measure what's happening everywhere. And it feels to me like the gusts are blowing the right way.

I was six when the UN's 'Earth Summit' took place in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992 and I still had a childlike understanding of environmental breakdown--that is, one not yet warped under the weight of capitalist realism. Though my main memory is my sister's snazzy 'save the rainforest' pencil case.

Even then, it seemed obvious that destroying the life system on which we all depend was a bad idea.

I was 12 when the Kyoto Protocol, an international agreement that called for industrialised nations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, was signed. I still remember my dad, a lifelong subscriber to the New Scientist, trying to explain his mixed emotions: it was something, but not enough.

By the time I was on the overnight coach to Copenhagen for COP15 in 2009, I was a hardened climate activist. While some had puffed the conference up into 'Hopenhagen', the members of our People & Planet student activist network had spent hours at a gathering in Leeds debating our response and concluded that the risk of pinning hope on a balloon is that it's likely to blow up in your face.

Perhaps the global climate movement would have got stuck in the sticky mess of the financial crisis without the comedown from the disappointment of COP15, but the inflation and then popping of that bubble of hope was certainly a part of the disaster, and it's hard not to feel like a decade of climate activism was lost.

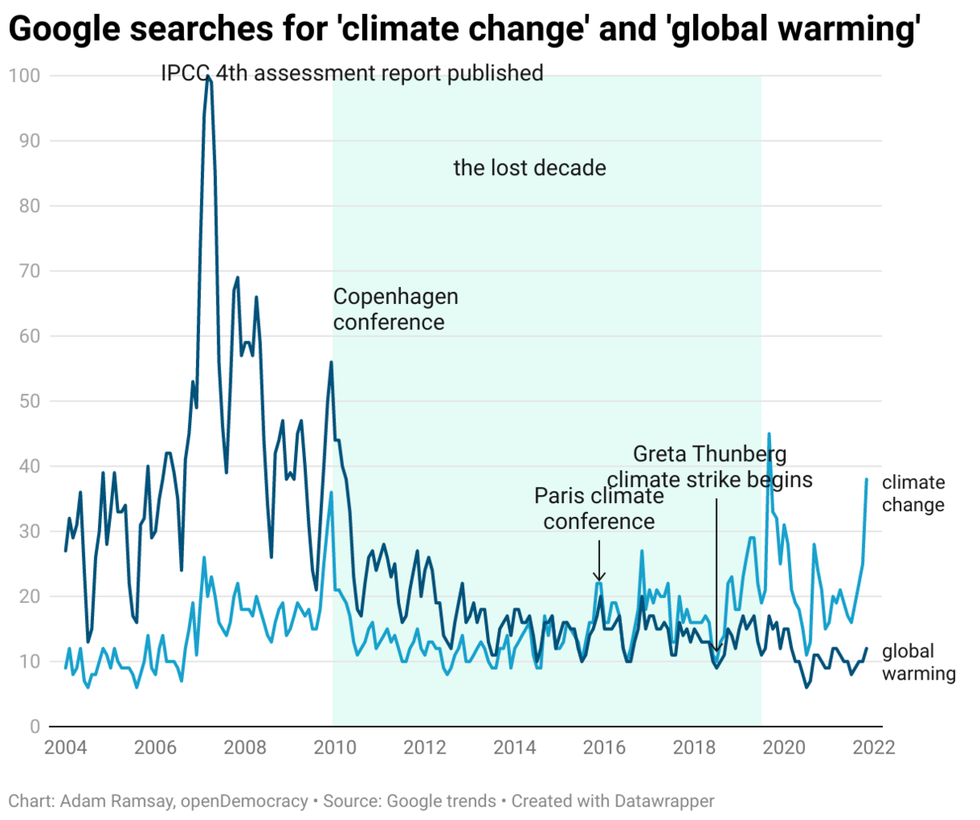

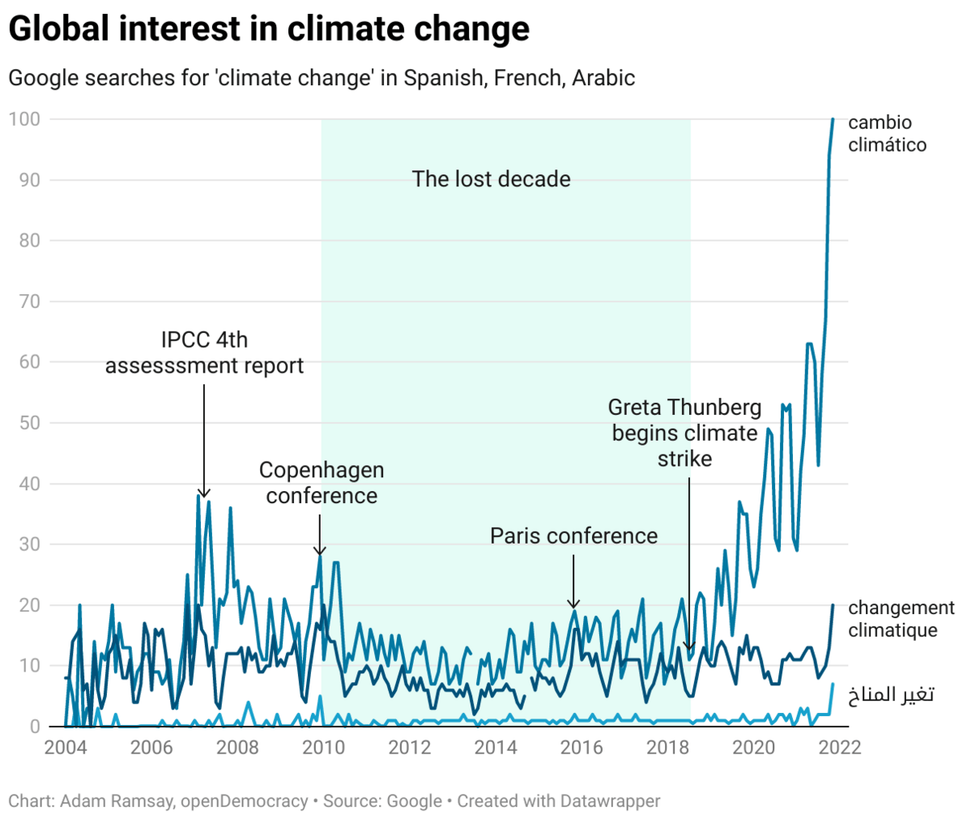

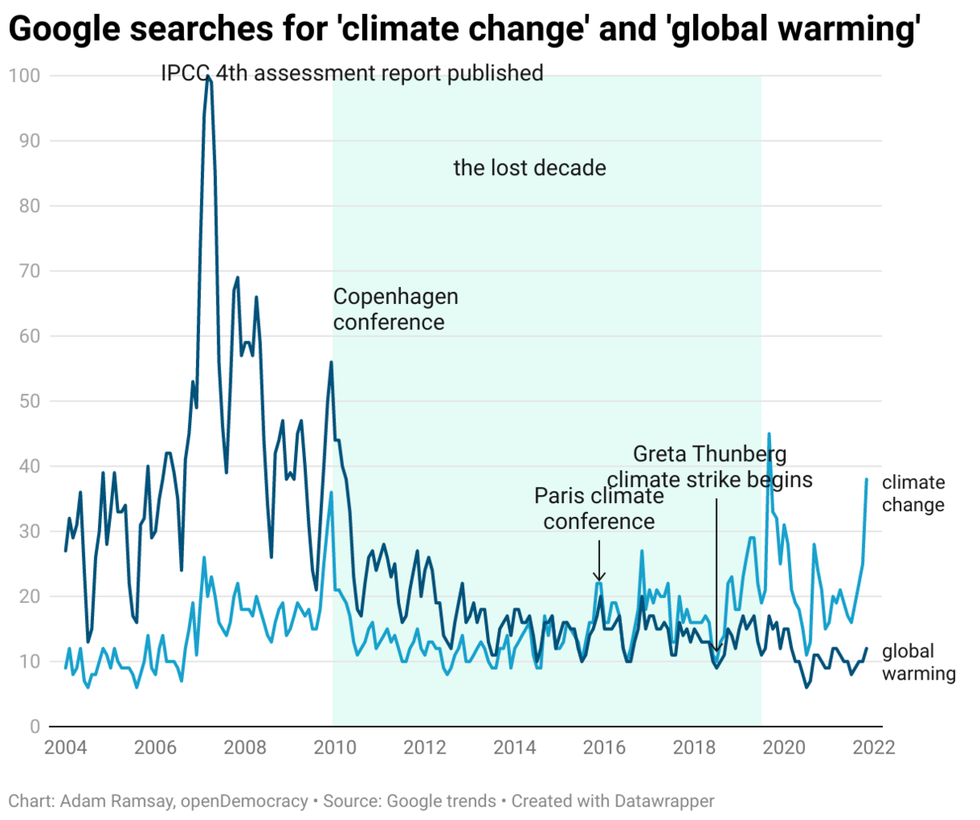

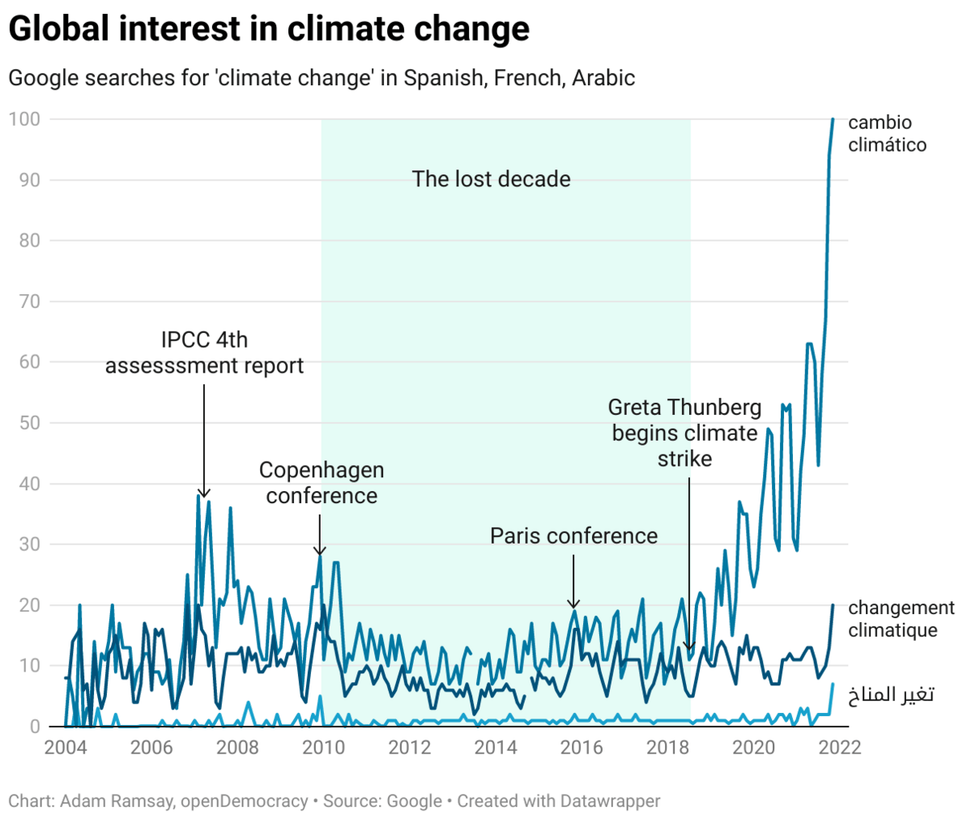

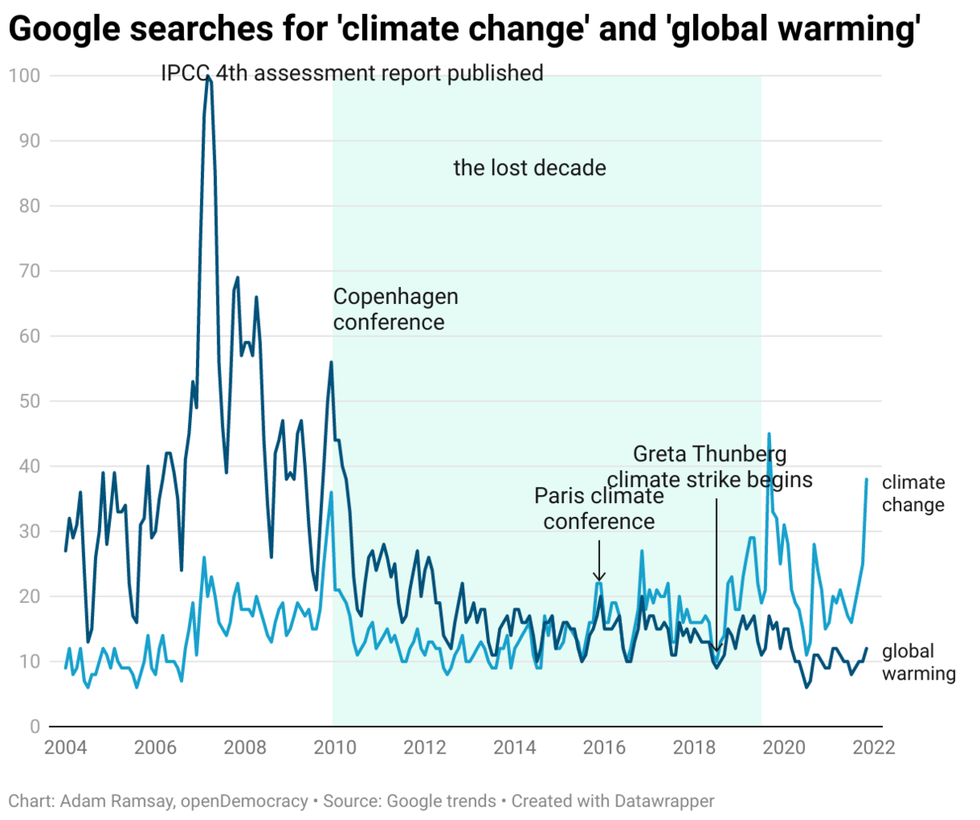

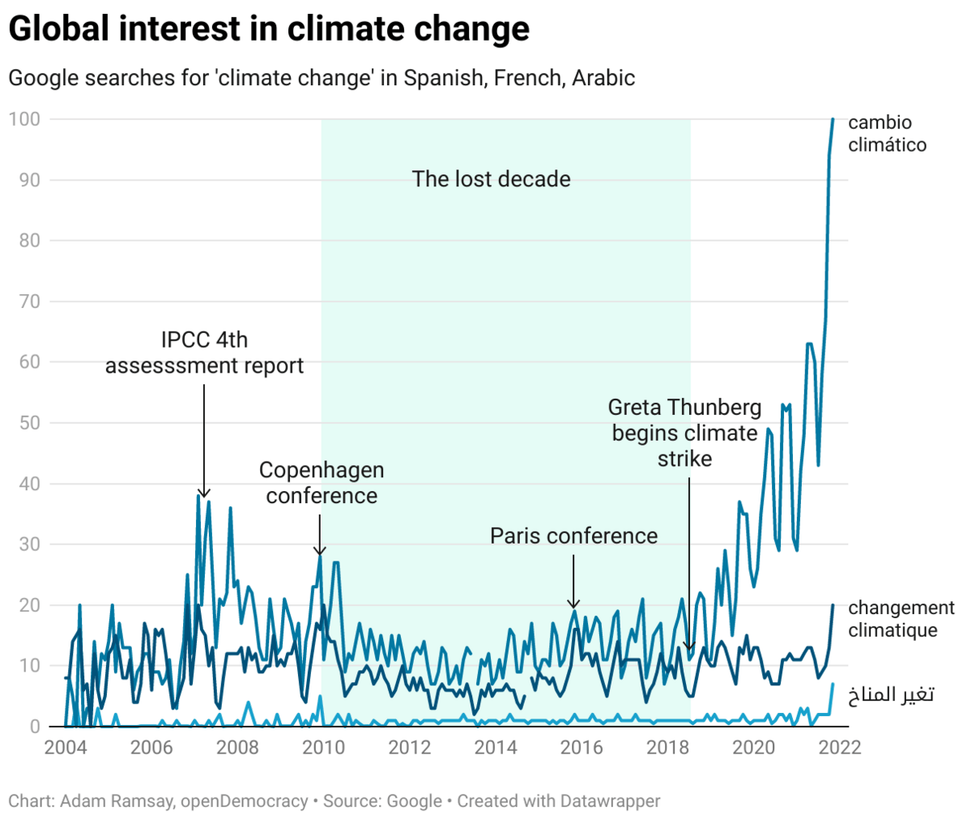

The graphs below show global Google searches for 'climate change' and 'global warming', followed by those for the equivalent terms in Spanish, French and Arabic.

Organisers had spent a year building for the conference, in the hope of giving the global climate-justice movement momentum and capturing the world's attention. But a series of coordinated terror attacks in the city shortly before the conference led the French government to declare a state of emergency.

As Alice Swift, a climate activist who teaches a course in environmental politics at Manchester University, said to me over lunch at my flat in Edinburgh on Friday: "The gendarmerie were decked in full armour with, like, guns and shit."

Many of the protests were cancelled and the global surge in attention never came. Although the pledges made did firm up the world's acceptance of the facts of climate science, the sense that politicians had everything under control, that they would keep the world below 1.5oC of warming, compounded the lack of urgency. Global attention to, and organising around, climate change remained dissipated, though groups of dedicated activists worked hard to grow the global climate movement. What's now clear is that they ensured that it came back better.

Glasgow was very different.

Ende Gelande activists occupying a coal mine in 2016. | Ende Gelande Copyright: 350.org/Tim Wagner

Ende Gelande activists occupying a coal mine in 2016. | Ende Gelande Copyright: 350.org/Tim Wagner"In the dead of night [in August 2017], we spent hours getting to the edge of the Hambach coal mine," Swift told me. "And then we locked ourselves onto the coal conveyor belt, but not before I'd turned what I thought was the off button off."

I first met Alice more than a decade ago, when I was a staff member with People & Planet and she was one of the leading activists in our Birmingham University group. Since then, she's become a key organiser of the Ende Gelande network, which takes direct action occupying coal mines in Germany and increasingly acts as a hub for climate change direct-action groups across Europe.

"We got onto the conveyor belt, and then, not long afterwards, there was this big siren, this big, flashing light. And quickly, the conveyor belt started to go again. And then it was very rapid, and we were just sat on top of the conveyor belt, initially with our legs hanging over. And then we just looked at each other, we didn't even need to say a word, we whipped our legs up as the conveyor belt started going again.

"And in that moment, it was like being faced with my own mortality. I could die here, but also, I'm totally OK with that. I know that there might be friends and family not okay with that decision. But I'd have tried my best."

Ende Gelande, which means 'here and no further', has been active since 2015, attracting thousands of people from across Europe to its mass actions against German coal, many of whom have gone on to set up groups in their home countries, including Czechia, Italy and the Netherlands.

After a week of driving around Scotland supporting activists who have been arrested during the climate conference, Alice told me that she was "feeling really positive about the COP".

"Before I was a radical environmentalist," she said, "I was a nice, good, well-behaved, bourgeois, liberal environmentalist doing my bit and, you know, doing petitions and speaking to the Tory councillors of Rutland County Council as a good girl should."

There are a shitload of people prepared to get out on the streets--more than ever. It seems to be getting more radical.

Most people in power, she said, "genuinely believe that if we just educated people enough, then each person took on green lifestylism and did their little bit, then we'd be able to make change--or if they got this particular policy through or managed to do X, Y and Z, then things could be sorted out".

"They do genuinely believe that there can be a green capitalism. Lord knows if there can be a green capitalism and [if] the choice is between a green capitalism and an ecocidal fossil fuel capitalism, then I would choose the former. I just don't believe that [it exists]."

For her, "climate change has not happened out of nowhere", it's a direct consequence of the capitalist system.

And, as she sees it, the climate movement has gone on a similar journey to her.

For COP26, she said, "the coalition, from the off, was mobilising in a clearly anti-capitalist and intersectional way. And it wasn't just what they were saying in the run-up, but then what actually happened in practice, during the last two weeks in Glasgow.

At the huge demonstration on Saturday 6 November--when an estimated 100,000 people marched through the streets of Glasgow demanding action on climate change--"there were loads of trade union people, there were people saying 'housing justice is climate justice', 'migrant justice is climate justice', 'racial justice is climate justice', and making that really clear and overt," Swift said. "There were Indigenous people, there were people from the Global South, and their voices were platformed--hopefully not in a way that fetishised them too much, but with true solidarity."

In Germany, the radicalism of the Ende Gelande movement, along with the youth climate strikes and the violent impacts of climate change itself, has driven climate change to the top of the political agenda--overtaking COVID as a concern among voters in the months before the recent election.

If Swift is right, then that's going to increasingly be the case elsewhere in the world. "There are a shitload of people that are prepared to get out on the streets--more than I've ever seen. It just seems to be getting more radical. And necessarily so. Frontline voices are being elevated. Being able to have that presence, it's really important."

Julius Ng'oma, a climate activist from Malawi who's organising communities against oil drilling there, agrees. "There was great momentum, collaborations right from the pre-COPs to the COP," he told me.

"I hope the movement can be sustained beyond COP26. The Global North and South collaborations were good.

"We have also seen the largest mobilisation of movements during the first weekend of the COP which was indeed a great thing. I think it can be sustained as long as we don't backtrack on highlighting the common issues."

I met Teofilo Kukush Pati and Galois Flores Pizango outside the Wilson Street Pantry, a short walk from Glasgow Queen Street station. Pizango and I spoke for an hour--helped by his interpreter--about autonomy and social movements, and hunting birds with a blowpipe, and music, and how their once nomadic existence in the remotest corner of the Peruvian Amazon had been ended by the introduction of borders with Ecuador, and about balsa wood, and deforestation, and oil.

Pizango is the vice-president of the Wampis people, who for thousands of years have defended their two valleys in the Amazon from all kinds of incursions. Pati is their Pamuk--their president.

"The only way to defend our territories is to declare ourselves autonomous. The state should respect that," Pizango said.

"Based on our ancestral knowledge, since the times of our ancestors, we have cared for and protected our territory in the best way."

According to the vice-president, the Wampis territory is covered by "more than 1.3 million hectares of tropical rainforest and annually absorbs more than 57 million metric tonnes of carbon equivalent".

But under this land lies carbon in another form. Over the past few years, "there's been a series of [oil] companies that have come in and tried to drill. And they've all been driven off by the local people."

To do this, they've led protests on their land and travelled to major cities in Chile and the Netherlands to protest against oil extraction. They've drawn up careful environmental-impact assessments, which they've presented to the government, showing how oil firms are going to damage the area--and in 2015, they declared themselves autonomous, electing the government that my new friends currently lead.

In recent years, they said, the Peruvian government has gradually begun to accept their legitimacy, including coordinating its pandemic response with them.

While they don't seek independence--they told me that setting up their own state would be "complicated and dangerous"--they are increasingly behaving like their own government. And, while at COP26, they launched a 71-page climate strategy.

For them, the trip to Glasgow was a success. "COP26 has been a space in which to raise the voice of the Wampis Nation so that the world may know about the work we do to care for our territory, which should be recognised and supported by climate funds since our forests [extract] the carbon dioxide which the big companies generate to make themselves rich," Pizango said.

The Wampis people weren't the only autonomous Indigenous government to make themselves heard at COP26.

If the Amazon is the biggest rainforest in the world, then New Guinea is the third largest. For thousands of years, the Indigenous peoples of the island--now divided into Papua New Guinea and West Papua--have lived sustainably in this remarkable ecosystem, which has the greatest plant diversity of any island on earth.

But while Papua New Guinea is an independent country, West Papua is a colony of Indonesia and a victim of vast extractive forces. At an event in a marquee on the bank of the Clyde, I spoke to Benny Wenda, the interim president of the provisional government (in exile) of West Papua. His country has the world's largest gold reserves.

"Indonesia illegally occupied and illegally colonised West Papua. We're facing two crises: firstly, genocide and, secondly, ecocide," he said.

In response to the latter, he has launched what his interim government is calling a 'Green State Vision', which would make 'ecocide' a serious criminal offence, restore guardianship of natural resources to Indigenous authorities, combining Western democratic norms with local Papuan systems, and 'serve notice' on all extraction companies, including oil, gas, mining, logging and palm oil, requiring them to adhere to international environmental standards or cease operations.

These examples may seem like small details of the broader geopolitics of climate breakdown and biodiversity collapse. But though Indigenous peoples comprise only 5% of the world's population, their territories make up around a quarter of the planet and include around 80% of the planet's biodiversity.

"The only way to defend our territories is to declare ourselves autonomous."--Galois Flores Pizango, vice-president of the Indigenous Wampis people

In North America, a recent report found that Indigenous resistance--often civil disobedience--has stopped or delayed greenhouse gas pollution equivalent to at least a quarter of annual US and Canadian emissions. As openDemocracy reported last week, the Inuit government of Greenland recently banned drilling for oil and gas.

"We're just starting really and making contacts, including here at COP26, with other Indigenous nations, to strengthen coordination with them," Pizango said.

For decades, Western environmentalists sidelined and ignored Indigenous peoples, often calling for ecosystems to be 'saved' without any acknowledgement that people have lived sustainably in these places for tens or hundreds of thousands of years. Not only is this approach racist, and a sort of eco-colonialism, it is also a deep strategic failure. This is a failure to understand that the most important allies in protecting the world's lungs and stopping the carbon in its rocks from being mined will be the people who have managed to do this despite the onslaught of capitalism and imperialism for half a millennium.

At this climate conference, the main march was led by an Indigenous bloc. There was more recognition among activists of the realities of the imperialist context in which we exist and organise, which means a greater chance of genuinely uniting the vast majority of the world behind the need for climate action.

Perhaps what was most striking about COP26 wasn't the paucity of the detail, but the fact that pretty much every national leader clearly felt they had to say the right thing. Throughout the conference, I had the Independent newspaper's Facebook page push articles at me sponsored by the Saudi Green Initiative. I'm meant to believe that Mohammed

Bin Salman, who was last month called a psychopath by one of his own former intelligence officers, has taken a sudden interest in the future of humanity. Even Brazil's fascist president, Jair Bolsonaro, has had to pretend he's against deforestation now.

This isn't because these people have suddenly become great humanitarians, nor because they are actually going to do any of the things they say. In the case of Brazil--and Narendra Modi's India and Xi Jinping's China--the apparent change of direction on climate change is partly because domestic political pressure has grown. In different ways in each place, climate activists have organised and shifted the political agenda. It's also partly because these governments are starting to see the cost of the climate crisis on their own terrain.

It's also because progressives have transformed US climate politics. Climate activists who threw their weight behind Bernie Sanders have extracted serious demands from the Biden administration before lending it their energy and organising skills. And so, countries that want to cosy up to the White House now know they have to talk the talk on climate change.

COPs aren't the wind driving climate action, they are anemometers helping us measure that action.

We can and should be cynical about this talk. But we should also see that it's a sign of the growing power of the climate movement: even its strongest enemies have started to steal its language.

That means these enemies are weak. Which means real change is possible.

As Dearden said to me: "After Glasgow, the climate justice movement dominates the discourse on climate change. Like it or not, world leaders have to pay at least lip service to the idea that climate change needs massive changes to our neo-colonial global economy. That's a huge change from Paris, where we still had to argue with climate deniers.

"Of course, we shouldn't underestimate the task ahead or overestimate the time we've got. But I actually leave Glasgow more hopeful than I went--the movement is bigger and more radical than it ever has been. And that's the only way we'll get the massive change we need."

Political change doesn't come from conferences of senior politicians. It is hewn by the opposing forces of power politics that meet every time humans gather. Serious action on climate change will be secured by strong, organised and radical social movements, which demand that the way we organise human society must change. What COP26 showed us is that the climate justice movement is stronger, better organised, and more radical than ever, and that the new generation of young climate activists is tougher, stronger, better organised and a thousand times more numerous than we were at their age. And with this newfound power, the movement can change the world.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

If it wasn't for the greenhouse effect, the Earth would be as cold and dead as the far side of the moon.

The pulses of energy released by the sun's gravity smashing together hydrogen nuclei and fusing them into helium atoms have to travel the same 150 million kilometres to get to both the Earth and the moon. They arrive at each as the same mix of ultraviolet, infrared and visible light. At both, they heat up rocks, which aren't so dissimilar, which absorb that energy and emit it as warm, infrared radiation, with luxurious, long wavelengths.

But from the moon, this warmth slips freely back into space. On Earth, it has to navigate an atmosphere.

Oxygen and nitrogen particles, which make up 99.03% of our air, are tiny things, even by molecular standards. Just as thickets of grass don't trip up ambling giraffes, these gases don't interfere with reflected heat waves, which can straddle as much as a millimetre. Nor, for that matter, does argon, which makes up another 0.93%.

But around 0.04% of Earth's atmosphere is CO2; 0.00018% is methane (CH4); 0.00006% is ozone (O3) and 0.00003% is nitrogen oxide (NO2). These molecules are all bigger and more complex. They can bend and stretch and twist in a number of directions. And so, like a spindly hedge, they catch infrared radiation reflected by the Earth and bounce it back towards the planet. They do it with such astonishing power that those tiny quantities ensure that Earth isn't a cold, hard rock like the dark side of the moon, where the average temperature is -153degC. We have a warm, breathing and bountiful planet.

The potency of these gases is what makes them dangerous. When humans first set foot on the moon, CO2 made up only 0.03% of our air. The concentration of methane in the atmosphere has more than doubled since preindustrial times. Over the past 800,000 years--more than twice as long as homo sapiens has existed--concentrations of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere rarely exceeded 280 parts per billion (ppb). With the development of industrial agriculture over the past century, they've increased to 331ppb.

In theory, world leaders have been in Glasgow over the past fortnight to negotiate how to reduce emissions of these astonishingly potent gases. In reality, most seemed more interested in building soft power and blaming someone else. But what they don't seem to understand is that however much human power they accrue, it will be nothing next to the might of CO2, CH4, NO2 and O3, with their firm, covalent bonds forming a tight blanket around the only home we've ever known.

I've followed the annual cycle of UN climate negotiations for most of my life. This year, the conference, COP26, came to my home country, Scotland. For the past two weeks, I've been surrounded by climate activists from across the planet, old friends and new, thinking and gossiping and analysing together. And despite the shortcomings of the official conference itself, I was struck by how remarkably positive they felt.

The final text agreed in Glasgow is a pitiful prayer, begging for the forgiveness of these celestial compounds. It expresses "alarm and concern", pointing passively at the burning building and suggesting someone do something. It "stresses the urgency of increased ambition and action". But it is neither ambitious nor details any sprightly action.

It "notes with serious concern that the current provision of climate finance for adaptation is insufficient to respond to worsening climate change impacts in developing countr[ies]," and "notes with regret" that the promise of rich countries "to mobilize jointly $100bn per year by 2020" to help poorer countries cope with the climate crisis "has not yet been met". I remember a landlord I had once noting that, with regret, he was increasing my rent.

It "recognizes that limiting global warming to 1.5degC by 2100 requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions" and "invites" governments "to consider further opportunities" to reduce emissions. It "calls upon" them to "accelerate efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies" as though this wasn't a document drafted by those very governments; as though phasing out all subsidies for fossil fuels wasn't what we needed to do a generation ago. What we must do in the coming years is stop burning them entirely.

There's not much reason to believe the governments that signed the COP26 draft will take action.

Funding for loss and damage done by climate change caused by the rich to the lives and infrastructure of the impoverished was blocked by the UK, EU and US. The Global Methane Pledge, an initiative announced by the EU and the US at the start of COP26, is largely about making leaky fossil fuel infrastructure more efficient--the lowest of low-hanging fruits. The pledge by some countries to end deforestation by 2030 has left many Indigenous activists who live in those forests with rolling eyes, and the new voluntary nationally determined contributions don't add up to enough to prevent 1.5degC of warming.

In any case, there's not much reason to believe the governments that signed the draft will take action. The world banned torture in 1987, but most states signed the convention, then ignored it.

None of this should surprise us. After all, the conference was built atop a crumbling neoliberal world order. Even its stated aim--to find ways to reach 'net zero' by the middle of the century--is dubious.

"This term is being used to cover up a multitude of sins. Because when people are talking about net zero, they're essentially talking about offsetting," said Nick Dearden, director of the non-governmental organisation, Global Justice Now, when chatting with me in a cafe on the Broomielaw, once the heart of Glasgow's shipbuilding district.

Of the conference's climate finance deal, which was agreed last Tuesday under the gavel of "rockstar central banker" and, if rumours are to be believed, wannabe Canadian prime minister Mark Carney, Dearden added: "A lot of this finance package is about net zero in that sense--offsetting emissions, which doesn't necessarily mean reducing your emissions at all."

It could mean increasing your emissions, while paying to 'offset' them with something else "which may or may not be useful," or even worse, offsetting them "with the vague notion that some as yet unidentified technology might help us to reduce these emissions," he said.

Perhaps most importantly, the 'net' in net zero often represents false accounting: you can't plant trees to make up for flights taken by your firm, because we need to both reforest the world and stop flying.

Any cynicism about carbon-trading and notions of 'net zero' is surely confirmed when you look at who is pushing them. The International Emissions Trading Association, which hosted a space at the core of COP26, is a representative body for many of the world's biggest polluters.

"The heart of it is that the government is obsessed with nudging the market," said Dearden. "And, of course, it isn't going to work. The market is going to be completely unable to deal with what's happening.

"Ultimately, you look at the global economy that we've created over the last 40 years, the neoliberal global economy--that's what's driving climate change. And no wonder, because the logic at the heart of that economy is that there is no right more important than the right to make profit.

"The whole economy is geared towards extremely short-term profit maximisation, no matter what the consequences are. And so what that essentially means is that you extract from workers, you extract from the Global South, you extract from the environment, you extract from future generations in order to make a profit today.

"Most of those issues around the global economy were not even on the agenda, not even talked about here at all. I think that goes to the heart of what the problem is. The governments, like the British government, that are really driving the process, want as much as possible to stay the same. They certainly don't want to interfere in rules that were put there in the first place to keep some countries rich, and some people rich and other countries poor.

"We have a global economy which hands monopoly power to massive corporations so they can extract rent from the rest of the world," he said. The World Trade Organization's 1995 Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (known as 'TRIPS') is one example of something that wasn't on the agenda at COP26 but should have been.

"The TRIPS agreement was created by the pharmaceutical industry so that they could exert monopoly power on the rest of the world and profiteer. That's been bad enough when it comes to vaccines and essential medicines. Imagine what that's going to be like when a handful of multinational corporations monopolise the green technologies that we need to run low carbon economies. We need to begin dismantling it, we need to put climate waivers in at least as a minimum, exactly like we're talking about with vaccines."

But these sorts of ideas, he added, are "not even mentioned by anybody ... It's just nowhere in the discussion".

For the British government, COP26 was a chance to take on a starring role in the soap opera of global politics. By that measure, the whole thing was a failure. The hosts won the 'carbon dinosaurs' award on the first day for making the conference what climate activist Greta Thunberg described as the "most excluding COP ever". The waits in lengthy outdoor queues, as winds swept up the River Clyde, were the talk of the first couple of days. As journalist George Monbiot pointed out, Boris Johnson fell asleep in the opening plenary then shot off in a private jet for dinner with a climate sceptic.

The only reason I can think of that the UK government chose Glasgow as a location was in the hope of upstaging Nicola Sturgeon on her own territory, and in that, it clearly failed. Scotland's first minister looked like the true host in her home city. Without a seat at the table, she stood on the stage. This weekend, a Scottish National Party (SNP) activist delivered a leaflet to every house on my street: "Scotland helped lead the world into the industrial age. Now, we're proud to help lead the world into the net-zero age."

If the SNP can rely on its vast membership to deliver its message, then the Tories have to fall back on the official media, which, in the UK, has largely divided into two categories: those that have declared the whole thing a success and those that blame India and China for its failure.

"By focusing only on coal and not including oil and gas, this text would disproportionately impact certain developing countries like China and India. India said in negotiations that all fossil fuels must be phased down, in an equitable manner. This is quite a reasonable response that is supported by a broad coalition of civil society groups which, earlier at COP26, released a report about how this might be done. A globally equitable fossil fuel phase-out is essential for the just, feminist and green transitions that countries need to make.

"But the United States framed this as India trying to block text on fossil fuels ... Knowing that many will not examine the claims critically, the United States is publicly claiming credit for getting fossil fuel language into the text while painting developing countries as the blockers. Meanwhile, of course, the Biden administration refuses to shut down new fossil fuel infrastructure at home."

The biggest change in the economics of fossil fuels over the past decade is that Barack Obama's fracking revolution in the US transformed the world's biggest oil consumer into its biggest producer. And while headlines accurately emphasised that coal is a particularly filthy fuel, they largely ignored how polluting America's new fracking habit is. A NASA study in 2018 found that the process of smashing up the ground to access hard-to-reach reserves often leads to vast leakages of natural gas--and has delivered a surge in methane emissions since 2006.

As Blutus Mbambi, a young climate activist from Zambia, said to me this week, "it is disappointing that only coal was mentioned at the COP26. This gives a free pass to the rich countries who have been extracting and polluting for over a century to continue producing oil and gas."

In this context, it's not surprising that China and India--the world's largest coal producers--wanted a more general phasing out of fossil fuels, whereas the US, which is the world's biggest oil producer, wanted to focus firmly on coal.

Much of the coverage has also separated this last-minute argument in the conference's overtime from ongoing discussions about climate finance. A vast portion of Britain's wealth comes from its plunder of India--and to a lesser extent, China--over centuries. Yet the UK, along with other wealthy countries, is still failing to meet promised funding to help formerly colonised countries like India meet the challenge of the climate crisis. China is, in many ways, taking more actual action to slash its emissions than most Western countries. In this context, attempts by the Western press to blame these countries for the failure of Johnson's COP26 need to be seen as the propaganda they are.

Despite all of that, COP26 filled me with hope. Because politics doesn't happen at big glitzy conferences. It happens in every home and workplace in the world. COPs aren't the wind that drives climate action, they are anemometers helping us measure what's happening everywhere. And it feels to me like the gusts are blowing the right way.

I was six when the UN's 'Earth Summit' took place in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992 and I still had a childlike understanding of environmental breakdown--that is, one not yet warped under the weight of capitalist realism. Though my main memory is my sister's snazzy 'save the rainforest' pencil case.

Even then, it seemed obvious that destroying the life system on which we all depend was a bad idea.

I was 12 when the Kyoto Protocol, an international agreement that called for industrialised nations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, was signed. I still remember my dad, a lifelong subscriber to the New Scientist, trying to explain his mixed emotions: it was something, but not enough.

By the time I was on the overnight coach to Copenhagen for COP15 in 2009, I was a hardened climate activist. While some had puffed the conference up into 'Hopenhagen', the members of our People & Planet student activist network had spent hours at a gathering in Leeds debating our response and concluded that the risk of pinning hope on a balloon is that it's likely to blow up in your face.

Perhaps the global climate movement would have got stuck in the sticky mess of the financial crisis without the comedown from the disappointment of COP15, but the inflation and then popping of that bubble of hope was certainly a part of the disaster, and it's hard not to feel like a decade of climate activism was lost.

The graphs below show global Google searches for 'climate change' and 'global warming', followed by those for the equivalent terms in Spanish, French and Arabic.

Organisers had spent a year building for the conference, in the hope of giving the global climate-justice movement momentum and capturing the world's attention. But a series of coordinated terror attacks in the city shortly before the conference led the French government to declare a state of emergency.

As Alice Swift, a climate activist who teaches a course in environmental politics at Manchester University, said to me over lunch at my flat in Edinburgh on Friday: "The gendarmerie were decked in full armour with, like, guns and shit."

Many of the protests were cancelled and the global surge in attention never came. Although the pledges made did firm up the world's acceptance of the facts of climate science, the sense that politicians had everything under control, that they would keep the world below 1.5oC of warming, compounded the lack of urgency. Global attention to, and organising around, climate change remained dissipated, though groups of dedicated activists worked hard to grow the global climate movement. What's now clear is that they ensured that it came back better.

Glasgow was very different.

Ende Gelande activists occupying a coal mine in 2016. | Ende Gelande Copyright: 350.org/Tim Wagner

Ende Gelande activists occupying a coal mine in 2016. | Ende Gelande Copyright: 350.org/Tim Wagner"In the dead of night [in August 2017], we spent hours getting to the edge of the Hambach coal mine," Swift told me. "And then we locked ourselves onto the coal conveyor belt, but not before I'd turned what I thought was the off button off."

I first met Alice more than a decade ago, when I was a staff member with People & Planet and she was one of the leading activists in our Birmingham University group. Since then, she's become a key organiser of the Ende Gelande network, which takes direct action occupying coal mines in Germany and increasingly acts as a hub for climate change direct-action groups across Europe.

"We got onto the conveyor belt, and then, not long afterwards, there was this big siren, this big, flashing light. And quickly, the conveyor belt started to go again. And then it was very rapid, and we were just sat on top of the conveyor belt, initially with our legs hanging over. And then we just looked at each other, we didn't even need to say a word, we whipped our legs up as the conveyor belt started going again.

"And in that moment, it was like being faced with my own mortality. I could die here, but also, I'm totally OK with that. I know that there might be friends and family not okay with that decision. But I'd have tried my best."

Ende Gelande, which means 'here and no further', has been active since 2015, attracting thousands of people from across Europe to its mass actions against German coal, many of whom have gone on to set up groups in their home countries, including Czechia, Italy and the Netherlands.

After a week of driving around Scotland supporting activists who have been arrested during the climate conference, Alice told me that she was "feeling really positive about the COP".

"Before I was a radical environmentalist," she said, "I was a nice, good, well-behaved, bourgeois, liberal environmentalist doing my bit and, you know, doing petitions and speaking to the Tory councillors of Rutland County Council as a good girl should."

There are a shitload of people prepared to get out on the streets--more than ever. It seems to be getting more radical.

Most people in power, she said, "genuinely believe that if we just educated people enough, then each person took on green lifestylism and did their little bit, then we'd be able to make change--or if they got this particular policy through or managed to do X, Y and Z, then things could be sorted out".

"They do genuinely believe that there can be a green capitalism. Lord knows if there can be a green capitalism and [if] the choice is between a green capitalism and an ecocidal fossil fuel capitalism, then I would choose the former. I just don't believe that [it exists]."

For her, "climate change has not happened out of nowhere", it's a direct consequence of the capitalist system.

And, as she sees it, the climate movement has gone on a similar journey to her.

For COP26, she said, "the coalition, from the off, was mobilising in a clearly anti-capitalist and intersectional way. And it wasn't just what they were saying in the run-up, but then what actually happened in practice, during the last two weeks in Glasgow.

At the huge demonstration on Saturday 6 November--when an estimated 100,000 people marched through the streets of Glasgow demanding action on climate change--"there were loads of trade union people, there were people saying 'housing justice is climate justice', 'migrant justice is climate justice', 'racial justice is climate justice', and making that really clear and overt," Swift said. "There were Indigenous people, there were people from the Global South, and their voices were platformed--hopefully not in a way that fetishised them too much, but with true solidarity."

In Germany, the radicalism of the Ende Gelande movement, along with the youth climate strikes and the violent impacts of climate change itself, has driven climate change to the top of the political agenda--overtaking COVID as a concern among voters in the months before the recent election.

If Swift is right, then that's going to increasingly be the case elsewhere in the world. "There are a shitload of people that are prepared to get out on the streets--more than I've ever seen. It just seems to be getting more radical. And necessarily so. Frontline voices are being elevated. Being able to have that presence, it's really important."

Julius Ng'oma, a climate activist from Malawi who's organising communities against oil drilling there, agrees. "There was great momentum, collaborations right from the pre-COPs to the COP," he told me.

"I hope the movement can be sustained beyond COP26. The Global North and South collaborations were good.

"We have also seen the largest mobilisation of movements during the first weekend of the COP which was indeed a great thing. I think it can be sustained as long as we don't backtrack on highlighting the common issues."

I met Teofilo Kukush Pati and Galois Flores Pizango outside the Wilson Street Pantry, a short walk from Glasgow Queen Street station. Pizango and I spoke for an hour--helped by his interpreter--about autonomy and social movements, and hunting birds with a blowpipe, and music, and how their once nomadic existence in the remotest corner of the Peruvian Amazon had been ended by the introduction of borders with Ecuador, and about balsa wood, and deforestation, and oil.

Pizango is the vice-president of the Wampis people, who for thousands of years have defended their two valleys in the Amazon from all kinds of incursions. Pati is their Pamuk--their president.

"The only way to defend our territories is to declare ourselves autonomous. The state should respect that," Pizango said.

"Based on our ancestral knowledge, since the times of our ancestors, we have cared for and protected our territory in the best way."

According to the vice-president, the Wampis territory is covered by "more than 1.3 million hectares of tropical rainforest and annually absorbs more than 57 million metric tonnes of carbon equivalent".

But under this land lies carbon in another form. Over the past few years, "there's been a series of [oil] companies that have come in and tried to drill. And they've all been driven off by the local people."

To do this, they've led protests on their land and travelled to major cities in Chile and the Netherlands to protest against oil extraction. They've drawn up careful environmental-impact assessments, which they've presented to the government, showing how oil firms are going to damage the area--and in 2015, they declared themselves autonomous, electing the government that my new friends currently lead.

In recent years, they said, the Peruvian government has gradually begun to accept their legitimacy, including coordinating its pandemic response with them.

While they don't seek independence--they told me that setting up their own state would be "complicated and dangerous"--they are increasingly behaving like their own government. And, while at COP26, they launched a 71-page climate strategy.

For them, the trip to Glasgow was a success. "COP26 has been a space in which to raise the voice of the Wampis Nation so that the world may know about the work we do to care for our territory, which should be recognised and supported by climate funds since our forests [extract] the carbon dioxide which the big companies generate to make themselves rich," Pizango said.

The Wampis people weren't the only autonomous Indigenous government to make themselves heard at COP26.

If the Amazon is the biggest rainforest in the world, then New Guinea is the third largest. For thousands of years, the Indigenous peoples of the island--now divided into Papua New Guinea and West Papua--have lived sustainably in this remarkable ecosystem, which has the greatest plant diversity of any island on earth.

But while Papua New Guinea is an independent country, West Papua is a colony of Indonesia and a victim of vast extractive forces. At an event in a marquee on the bank of the Clyde, I spoke to Benny Wenda, the interim president of the provisional government (in exile) of West Papua. His country has the world's largest gold reserves.

"Indonesia illegally occupied and illegally colonised West Papua. We're facing two crises: firstly, genocide and, secondly, ecocide," he said.

In response to the latter, he has launched what his interim government is calling a 'Green State Vision', which would make 'ecocide' a serious criminal offence, restore guardianship of natural resources to Indigenous authorities, combining Western democratic norms with local Papuan systems, and 'serve notice' on all extraction companies, including oil, gas, mining, logging and palm oil, requiring them to adhere to international environmental standards or cease operations.

These examples may seem like small details of the broader geopolitics of climate breakdown and biodiversity collapse. But though Indigenous peoples comprise only 5% of the world's population, their territories make up around a quarter of the planet and include around 80% of the planet's biodiversity.

"The only way to defend our territories is to declare ourselves autonomous."--Galois Flores Pizango, vice-president of the Indigenous Wampis people

In North America, a recent report found that Indigenous resistance--often civil disobedience--has stopped or delayed greenhouse gas pollution equivalent to at least a quarter of annual US and Canadian emissions. As openDemocracy reported last week, the Inuit government of Greenland recently banned drilling for oil and gas.

"We're just starting really and making contacts, including here at COP26, with other Indigenous nations, to strengthen coordination with them," Pizango said.

For decades, Western environmentalists sidelined and ignored Indigenous peoples, often calling for ecosystems to be 'saved' without any acknowledgement that people have lived sustainably in these places for tens or hundreds of thousands of years. Not only is this approach racist, and a sort of eco-colonialism, it is also a deep strategic failure. This is a failure to understand that the most important allies in protecting the world's lungs and stopping the carbon in its rocks from being mined will be the people who have managed to do this despite the onslaught of capitalism and imperialism for half a millennium.

At this climate conference, the main march was led by an Indigenous bloc. There was more recognition among activists of the realities of the imperialist context in which we exist and organise, which means a greater chance of genuinely uniting the vast majority of the world behind the need for climate action.

Perhaps what was most striking about COP26 wasn't the paucity of the detail, but the fact that pretty much every national leader clearly felt they had to say the right thing. Throughout the conference, I had the Independent newspaper's Facebook page push articles at me sponsored by the Saudi Green Initiative. I'm meant to believe that Mohammed

Bin Salman, who was last month called a psychopath by one of his own former intelligence officers, has taken a sudden interest in the future of humanity. Even Brazil's fascist president, Jair Bolsonaro, has had to pretend he's against deforestation now.

This isn't because these people have suddenly become great humanitarians, nor because they are actually going to do any of the things they say. In the case of Brazil--and Narendra Modi's India and Xi Jinping's China--the apparent change of direction on climate change is partly because domestic political pressure has grown. In different ways in each place, climate activists have organised and shifted the political agenda. It's also partly because these governments are starting to see the cost of the climate crisis on their own terrain.

It's also because progressives have transformed US climate politics. Climate activists who threw their weight behind Bernie Sanders have extracted serious demands from the Biden administration before lending it their energy and organising skills. And so, countries that want to cosy up to the White House now know they have to talk the talk on climate change.

COPs aren't the wind driving climate action, they are anemometers helping us measure that action.

We can and should be cynical about this talk. But we should also see that it's a sign of the growing power of the climate movement: even its strongest enemies have started to steal its language.

That means these enemies are weak. Which means real change is possible.

As Dearden said to me: "After Glasgow, the climate justice movement dominates the discourse on climate change. Like it or not, world leaders have to pay at least lip service to the idea that climate change needs massive changes to our neo-colonial global economy. That's a huge change from Paris, where we still had to argue with climate deniers.

"Of course, we shouldn't underestimate the task ahead or overestimate the time we've got. But I actually leave Glasgow more hopeful than I went--the movement is bigger and more radical than it ever has been. And that's the only way we'll get the massive change we need."

Political change doesn't come from conferences of senior politicians. It is hewn by the opposing forces of power politics that meet every time humans gather. Serious action on climate change will be secured by strong, organised and radical social movements, which demand that the way we organise human society must change. What COP26 showed us is that the climate justice movement is stronger, better organised, and more radical than ever, and that the new generation of young climate activists is tougher, stronger, better organised and a thousand times more numerous than we were at their age. And with this newfound power, the movement can change the world.

If it wasn't for the greenhouse effect, the Earth would be as cold and dead as the far side of the moon.

The pulses of energy released by the sun's gravity smashing together hydrogen nuclei and fusing them into helium atoms have to travel the same 150 million kilometres to get to both the Earth and the moon. They arrive at each as the same mix of ultraviolet, infrared and visible light. At both, they heat up rocks, which aren't so dissimilar, which absorb that energy and emit it as warm, infrared radiation, with luxurious, long wavelengths.

But from the moon, this warmth slips freely back into space. On Earth, it has to navigate an atmosphere.

Oxygen and nitrogen particles, which make up 99.03% of our air, are tiny things, even by molecular standards. Just as thickets of grass don't trip up ambling giraffes, these gases don't interfere with reflected heat waves, which can straddle as much as a millimetre. Nor, for that matter, does argon, which makes up another 0.93%.

But around 0.04% of Earth's atmosphere is CO2; 0.00018% is methane (CH4); 0.00006% is ozone (O3) and 0.00003% is nitrogen oxide (NO2). These molecules are all bigger and more complex. They can bend and stretch and twist in a number of directions. And so, like a spindly hedge, they catch infrared radiation reflected by the Earth and bounce it back towards the planet. They do it with such astonishing power that those tiny quantities ensure that Earth isn't a cold, hard rock like the dark side of the moon, where the average temperature is -153degC. We have a warm, breathing and bountiful planet.

The potency of these gases is what makes them dangerous. When humans first set foot on the moon, CO2 made up only 0.03% of our air. The concentration of methane in the atmosphere has more than doubled since preindustrial times. Over the past 800,000 years--more than twice as long as homo sapiens has existed--concentrations of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere rarely exceeded 280 parts per billion (ppb). With the development of industrial agriculture over the past century, they've increased to 331ppb.

In theory, world leaders have been in Glasgow over the past fortnight to negotiate how to reduce emissions of these astonishingly potent gases. In reality, most seemed more interested in building soft power and blaming someone else. But what they don't seem to understand is that however much human power they accrue, it will be nothing next to the might of CO2, CH4, NO2 and O3, with their firm, covalent bonds forming a tight blanket around the only home we've ever known.

I've followed the annual cycle of UN climate negotiations for most of my life. This year, the conference, COP26, came to my home country, Scotland. For the past two weeks, I've been surrounded by climate activists from across the planet, old friends and new, thinking and gossiping and analysing together. And despite the shortcomings of the official conference itself, I was struck by how remarkably positive they felt.

The final text agreed in Glasgow is a pitiful prayer, begging for the forgiveness of these celestial compounds. It expresses "alarm and concern", pointing passively at the burning building and suggesting someone do something. It "stresses the urgency of increased ambition and action". But it is neither ambitious nor details any sprightly action.

It "notes with serious concern that the current provision of climate finance for adaptation is insufficient to respond to worsening climate change impacts in developing countr[ies]," and "notes with regret" that the promise of rich countries "to mobilize jointly $100bn per year by 2020" to help poorer countries cope with the climate crisis "has not yet been met". I remember a landlord I had once noting that, with regret, he was increasing my rent.

It "recognizes that limiting global warming to 1.5degC by 2100 requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions" and "invites" governments "to consider further opportunities" to reduce emissions. It "calls upon" them to "accelerate efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies" as though this wasn't a document drafted by those very governments; as though phasing out all subsidies for fossil fuels wasn't what we needed to do a generation ago. What we must do in the coming years is stop burning them entirely.

There's not much reason to believe the governments that signed the COP26 draft will take action.

Funding for loss and damage done by climate change caused by the rich to the lives and infrastructure of the impoverished was blocked by the UK, EU and US. The Global Methane Pledge, an initiative announced by the EU and the US at the start of COP26, is largely about making leaky fossil fuel infrastructure more efficient--the lowest of low-hanging fruits. The pledge by some countries to end deforestation by 2030 has left many Indigenous activists who live in those forests with rolling eyes, and the new voluntary nationally determined contributions don't add up to enough to prevent 1.5degC of warming.

In any case, there's not much reason to believe the governments that signed the draft will take action. The world banned torture in 1987, but most states signed the convention, then ignored it.

None of this should surprise us. After all, the conference was built atop a crumbling neoliberal world order. Even its stated aim--to find ways to reach 'net zero' by the middle of the century--is dubious.

"This term is being used to cover up a multitude of sins. Because when people are talking about net zero, they're essentially talking about offsetting," said Nick Dearden, director of the non-governmental organisation, Global Justice Now, when chatting with me in a cafe on the Broomielaw, once the heart of Glasgow's shipbuilding district.

Of the conference's climate finance deal, which was agreed last Tuesday under the gavel of "rockstar central banker" and, if rumours are to be believed, wannabe Canadian prime minister Mark Carney, Dearden added: "A lot of this finance package is about net zero in that sense--offsetting emissions, which doesn't necessarily mean reducing your emissions at all."

It could mean increasing your emissions, while paying to 'offset' them with something else "which may or may not be useful," or even worse, offsetting them "with the vague notion that some as yet unidentified technology might help us to reduce these emissions," he said.

Perhaps most importantly, the 'net' in net zero often represents false accounting: you can't plant trees to make up for flights taken by your firm, because we need to both reforest the world and stop flying.

Any cynicism about carbon-trading and notions of 'net zero' is surely confirmed when you look at who is pushing them. The International Emissions Trading Association, which hosted a space at the core of COP26, is a representative body for many of the world's biggest polluters.

"The heart of it is that the government is obsessed with nudging the market," said Dearden. "And, of course, it isn't going to work. The market is going to be completely unable to deal with what's happening.

"Ultimately, you look at the global economy that we've created over the last 40 years, the neoliberal global economy--that's what's driving climate change. And no wonder, because the logic at the heart of that economy is that there is no right more important than the right to make profit.

"The whole economy is geared towards extremely short-term profit maximisation, no matter what the consequences are. And so what that essentially means is that you extract from workers, you extract from the Global South, you extract from the environment, you extract from future generations in order to make a profit today.

"Most of those issues around the global economy were not even on the agenda, not even talked about here at all. I think that goes to the heart of what the problem is. The governments, like the British government, that are really driving the process, want as much as possible to stay the same. They certainly don't want to interfere in rules that were put there in the first place to keep some countries rich, and some people rich and other countries poor.

"We have a global economy which hands monopoly power to massive corporations so they can extract rent from the rest of the world," he said. The World Trade Organization's 1995 Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (known as 'TRIPS') is one example of something that wasn't on the agenda at COP26 but should have been.

"The TRIPS agreement was created by the pharmaceutical industry so that they could exert monopoly power on the rest of the world and profiteer. That's been bad enough when it comes to vaccines and essential medicines. Imagine what that's going to be like when a handful of multinational corporations monopolise the green technologies that we need to run low carbon economies. We need to begin dismantling it, we need to put climate waivers in at least as a minimum, exactly like we're talking about with vaccines."

But these sorts of ideas, he added, are "not even mentioned by anybody ... It's just nowhere in the discussion".

For the British government, COP26 was a chance to take on a starring role in the soap opera of global politics. By that measure, the whole thing was a failure. The hosts won the 'carbon dinosaurs' award on the first day for making the conference what climate activist Greta Thunberg described as the "most excluding COP ever". The waits in lengthy outdoor queues, as winds swept up the River Clyde, were the talk of the first couple of days. As journalist George Monbiot pointed out, Boris Johnson fell asleep in the opening plenary then shot off in a private jet for dinner with a climate sceptic.

The only reason I can think of that the UK government chose Glasgow as a location was in the hope of upstaging Nicola Sturgeon on her own territory, and in that, it clearly failed. Scotland's first minister looked like the true host in her home city. Without a seat at the table, she stood on the stage. This weekend, a Scottish National Party (SNP) activist delivered a leaflet to every house on my street: "Scotland helped lead the world into the industrial age. Now, we're proud to help lead the world into the net-zero age."

If the SNP can rely on its vast membership to deliver its message, then the Tories have to fall back on the official media, which, in the UK, has largely divided into two categories: those that have declared the whole thing a success and those that blame India and China for its failure.

"By focusing only on coal and not including oil and gas, this text would disproportionately impact certain developing countries like China and India. India said in negotiations that all fossil fuels must be phased down, in an equitable manner. This is quite a reasonable response that is supported by a broad coalition of civil society groups which, earlier at COP26, released a report about how this might be done. A globally equitable fossil fuel phase-out is essential for the just, feminist and green transitions that countries need to make.

"But the United States framed this as India trying to block text on fossil fuels ... Knowing that many will not examine the claims critically, the United States is publicly claiming credit for getting fossil fuel language into the text while painting developing countries as the blockers. Meanwhile, of course, the Biden administration refuses to shut down new fossil fuel infrastructure at home."

The biggest change in the economics of fossil fuels over the past decade is that Barack Obama's fracking revolution in the US transformed the world's biggest oil consumer into its biggest producer. And while headlines accurately emphasised that coal is a particularly filthy fuel, they largely ignored how polluting America's new fracking habit is. A NASA study in 2018 found that the process of smashing up the ground to access hard-to-reach reserves often leads to vast leakages of natural gas--and has delivered a surge in methane emissions since 2006.

As Blutus Mbambi, a young climate activist from Zambia, said to me this week, "it is disappointing that only coal was mentioned at the COP26. This gives a free pass to the rich countries who have been extracting and polluting for over a century to continue producing oil and gas."

In this context, it's not surprising that China and India--the world's largest coal producers--wanted a more general phasing out of fossil fuels, whereas the US, which is the world's biggest oil producer, wanted to focus firmly on coal.

Much of the coverage has also separated this last-minute argument in the conference's overtime from ongoing discussions about climate finance. A vast portion of Britain's wealth comes from its plunder of India--and to a lesser extent, China--over centuries. Yet the UK, along with other wealthy countries, is still failing to meet promised funding to help formerly colonised countries like India meet the challenge of the climate crisis. China is, in many ways, taking more actual action to slash its emissions than most Western countries. In this context, attempts by the Western press to blame these countries for the failure of Johnson's COP26 need to be seen as the propaganda they are.

Despite all of that, COP26 filled me with hope. Because politics doesn't happen at big glitzy conferences. It happens in every home and workplace in the world. COPs aren't the wind that drives climate action, they are anemometers helping us measure what's happening everywhere. And it feels to me like the gusts are blowing the right way.

I was six when the UN's 'Earth Summit' took place in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992 and I still had a childlike understanding of environmental breakdown--that is, one not yet warped under the weight of capitalist realism. Though my main memory is my sister's snazzy 'save the rainforest' pencil case.

Even then, it seemed obvious that destroying the life system on which we all depend was a bad idea.

I was 12 when the Kyoto Protocol, an international agreement that called for industrialised nations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, was signed. I still remember my dad, a lifelong subscriber to the New Scientist, trying to explain his mixed emotions: it was something, but not enough.

By the time I was on the overnight coach to Copenhagen for COP15 in 2009, I was a hardened climate activist. While some had puffed the conference up into 'Hopenhagen', the members of our People & Planet student activist network had spent hours at a gathering in Leeds debating our response and concluded that the risk of pinning hope on a balloon is that it's likely to blow up in your face.

Perhaps the global climate movement would have got stuck in the sticky mess of the financial crisis without the comedown from the disappointment of COP15, but the inflation and then popping of that bubble of hope was certainly a part of the disaster, and it's hard not to feel like a decade of climate activism was lost.

The graphs below show global Google searches for 'climate change' and 'global warming', followed by those for the equivalent terms in Spanish, French and Arabic.

Organisers had spent a year building for the conference, in the hope of giving the global climate-justice movement momentum and capturing the world's attention. But a series of coordinated terror attacks in the city shortly before the conference led the French government to declare a state of emergency.

As Alice Swift, a climate activist who teaches a course in environmental politics at Manchester University, said to me over lunch at my flat in Edinburgh on Friday: "The gendarmerie were decked in full armour with, like, guns and shit."