SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

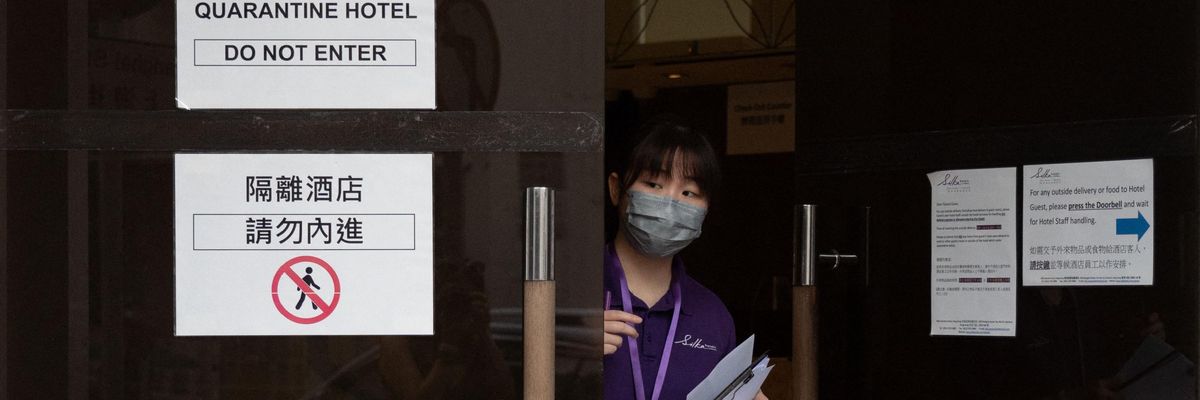

On October 30, 2021, a staff member walks out from a Covid-19 quarantine hotel in Hong Kong. Hong Kong's decision to descend deeper into international coronavirus isolation as rivals reopen is causing consternation among managers at multinationals who see no end to a zero-Covid strategy imposed by a leadership beholden to Beijing. (Photo: Bertha Wang / AFP via Getty Images)

As the new Omicron variant of Covid-19 threatens to eviscerate the false sense of security that political elites in many rich countries have felt since vaccines were rolled out at the beginning of the year, critics of China's zero-Covid strategy may want to carefully reflect on why they have been so quick to dismiss Beijing's stringent containment measures.

Covid-19 has always been more than a public health crisis. It is an economic and political crisis; an environmental and social crisis; a crisis of information and a crisis of trust.

An opinion piece published in the Financial Times earlier this month took aim at Beijing's approach to stamping out the virus, calling it a "global concern." At the end of October, the New York Times published an article warning China's zero-Covid strategy risks isolating the country, both diplomatically and economically. Around the same time, the Guardian published a similar story while CNN also reported on how China is being left behind as its regional neighbors "learn to live" with the virus. Similar sentiments have been echoed across the corporate media, from Time and the Washington Post to the Economist and ABC.

Many of these reports share the assumption that we've already seen the worst of the pandemic, and that Beijing's strong-arm approach to governance means it is unable to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances. But this is way off the mark. Covid-19 has always been more than a public health crisis. It is an economic and political crisis; an environmental and social crisis; a crisis of information and a crisis of trust. In other words, it is a crisis that goes to the heart of the global system, holding up a mirror to individual societies and peeling away all the old pretenses. Big Pharma's monopoly on vaccines mean the risk of new variants emerging and causing havoc could continue well into the future, according to the WHO, as an intellectual property regime backed by the likes of the UK and Germany perpetuates structural health inequalities rooted in much longer histories of imperialism and dependency. Economic inequalities mean shutdowns of the type favored by European governments have always been a pipe dream in the underdeveloped world, where restrictions on work and travel have proven especially deadly. The wealth of the super-rich has spiked since the beginning of the pandemic, but hundreds of millions across the world have been plunged into new and dangerous forms of poverty, overturning even the most basic and rudimentary gains in global development. Such precarity can only increase desperation, pushing vulnerable individuals and groups back into work even as the virus mutates and takes on potentially more dangerous forms.

Instead of being viewed as an inefficient outcome of authoritarian rule, perhaps China's zero-Covid strategy should then be seen for what it is: a highly effective, if often ham-fisted, response to what so far is the biggest global crisis of the 21st-century. New research by mathematicians at Peking University warns a loosening of restrictions in China could unleash upwards of 600,000 infections a day, overloading the healthcare system. Earlier this month, Zhong Nanshan, the country's leading respiratory disease expert, warned of the costs of ending its zero-Covid policy. Gao Fu, the head of the Chinese CDC, has also called for the strategy to be maintained. When the highly popular virologist Zhang Wenhong suggested China needs to learn to "live with the virus" back in August, the state-media backlash reflected not only the depth of feeling within the Chinese leadership but also very real insecurities about the potentially catastrophic consequences of adopting alternative approaches to epidemic control.

What many of the critics of Beijing's zero-Covid strategy ignore are the tremendous regional and urban/rural inequalities that structure reform-era Chinese society. Simplistic narratives of the country's historic rise have been internalized both inside and outside the country, reflected across political divides in the West: the right pushing "China threat" narratives, as certain segments of the left fantasize about how China's growing superpower status promises a better future for all. The glittering skylines of Beijing, Shenzhen and Shanghai tend to muddle and confuse, proving effective antidotes at concealing the country's stark socio-economic differences. While the urban middle-class in coastal centers have access to genuinely world-class hospitals, villagers are sometimes denied even rudimentary healthcare. Many rural migrants go without due to a hukou system that reduces hundreds of millions to effective second-class citizenship in the places they live and work. In a study of nearly 350 cities conducted last year, researchers found 98 had no top-class hospitals, whereas 93 had only one. In comparison, Beijing and Guangzhou each had more than 50. Scrape beneath the surface still, and the numbers are even more staggering. A report by the WHO from a few years ago shows how China's public health spending per capita was around half that of Algeria and Brazil and nearly one-third that of Panama, with the figures starker still when compared to those of advanced economies.

When the opinion pages of the Financial Times accuse Beijing of damaging international business by sticking to its zero-Covid strategy, they speak to and for global capitalist interests.

Few are more aware of the tremendous dislocations and inequities in China's domestic economy caused by four-decades of integrating into the global capitalist economy than China's political elite. Last year, Premier Li Keqiang publicly acknowledged that 600-million Chinese people remain poor. Since Hu Jintao and Wen Jiaobao came to power in 2003, genuine efforts have been made to rebalance growth and reduce rural/urban inequalities after the early decades of reform saw a general collapse in rural welfare and unprecedented levels of social unrest. As part of efforts to modernize rural areas by building a "new socialist countryside," the Hu-Wen government abolished agricultural taxes, expanded health insurance, increased educational services for rural children and introduced new forms of social welfare targeted at alleviating poverty. Similar policies have continued in the era of Xi Jinping, as Beijing announced an end to "extreme poverty"last year. The relaxing of some hukou restrictions, the revival of the Mao-era slogan "common prosperity"and the announcement of China's new "principle contradiction"in 2017--"between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people's ever-growing needs for a better life"--must also be understood within this context.

Yet so too must China's approach to Covid-19. Beijing's capacity to mobilize the entire apparatus of the state to stamp out sporadic outbreaks is arguably the system's greatest strength. But as Chuan have brilliantly articulated, it also responds to a fundamental weakness. When the opinion pages of the Financial Times accuse Beijing of damaging international business by sticking to its zero-Covid strategy, they speak to and for global capitalist interests. Lacking sensitivity to the uneven nature of Chinese development, the potential human catastrophe that Chinese researchers warn of does not feature in their calculations. To combat such hubris, the left must remain sensitive to the distortions and injustices of forty years of reform. This is not to deny the country's remarkable socio-economic achievements. But for millions of Chinese people still struggling to live a decent life, it is to say that if livelihoods are to continue improving, it will be because of, not in spite of, Beijing's relentless effort to eliminate infections whenever and wherever they arise.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As the new Omicron variant of Covid-19 threatens to eviscerate the false sense of security that political elites in many rich countries have felt since vaccines were rolled out at the beginning of the year, critics of China's zero-Covid strategy may want to carefully reflect on why they have been so quick to dismiss Beijing's stringent containment measures.

Covid-19 has always been more than a public health crisis. It is an economic and political crisis; an environmental and social crisis; a crisis of information and a crisis of trust.

An opinion piece published in the Financial Times earlier this month took aim at Beijing's approach to stamping out the virus, calling it a "global concern." At the end of October, the New York Times published an article warning China's zero-Covid strategy risks isolating the country, both diplomatically and economically. Around the same time, the Guardian published a similar story while CNN also reported on how China is being left behind as its regional neighbors "learn to live" with the virus. Similar sentiments have been echoed across the corporate media, from Time and the Washington Post to the Economist and ABC.

Many of these reports share the assumption that we've already seen the worst of the pandemic, and that Beijing's strong-arm approach to governance means it is unable to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances. But this is way off the mark. Covid-19 has always been more than a public health crisis. It is an economic and political crisis; an environmental and social crisis; a crisis of information and a crisis of trust. In other words, it is a crisis that goes to the heart of the global system, holding up a mirror to individual societies and peeling away all the old pretenses. Big Pharma's monopoly on vaccines mean the risk of new variants emerging and causing havoc could continue well into the future, according to the WHO, as an intellectual property regime backed by the likes of the UK and Germany perpetuates structural health inequalities rooted in much longer histories of imperialism and dependency. Economic inequalities mean shutdowns of the type favored by European governments have always been a pipe dream in the underdeveloped world, where restrictions on work and travel have proven especially deadly. The wealth of the super-rich has spiked since the beginning of the pandemic, but hundreds of millions across the world have been plunged into new and dangerous forms of poverty, overturning even the most basic and rudimentary gains in global development. Such precarity can only increase desperation, pushing vulnerable individuals and groups back into work even as the virus mutates and takes on potentially more dangerous forms.

Instead of being viewed as an inefficient outcome of authoritarian rule, perhaps China's zero-Covid strategy should then be seen for what it is: a highly effective, if often ham-fisted, response to what so far is the biggest global crisis of the 21st-century. New research by mathematicians at Peking University warns a loosening of restrictions in China could unleash upwards of 600,000 infections a day, overloading the healthcare system. Earlier this month, Zhong Nanshan, the country's leading respiratory disease expert, warned of the costs of ending its zero-Covid policy. Gao Fu, the head of the Chinese CDC, has also called for the strategy to be maintained. When the highly popular virologist Zhang Wenhong suggested China needs to learn to "live with the virus" back in August, the state-media backlash reflected not only the depth of feeling within the Chinese leadership but also very real insecurities about the potentially catastrophic consequences of adopting alternative approaches to epidemic control.

What many of the critics of Beijing's zero-Covid strategy ignore are the tremendous regional and urban/rural inequalities that structure reform-era Chinese society. Simplistic narratives of the country's historic rise have been internalized both inside and outside the country, reflected across political divides in the West: the right pushing "China threat" narratives, as certain segments of the left fantasize about how China's growing superpower status promises a better future for all. The glittering skylines of Beijing, Shenzhen and Shanghai tend to muddle and confuse, proving effective antidotes at concealing the country's stark socio-economic differences. While the urban middle-class in coastal centers have access to genuinely world-class hospitals, villagers are sometimes denied even rudimentary healthcare. Many rural migrants go without due to a hukou system that reduces hundreds of millions to effective second-class citizenship in the places they live and work. In a study of nearly 350 cities conducted last year, researchers found 98 had no top-class hospitals, whereas 93 had only one. In comparison, Beijing and Guangzhou each had more than 50. Scrape beneath the surface still, and the numbers are even more staggering. A report by the WHO from a few years ago shows how China's public health spending per capita was around half that of Algeria and Brazil and nearly one-third that of Panama, with the figures starker still when compared to those of advanced economies.

When the opinion pages of the Financial Times accuse Beijing of damaging international business by sticking to its zero-Covid strategy, they speak to and for global capitalist interests.

Few are more aware of the tremendous dislocations and inequities in China's domestic economy caused by four-decades of integrating into the global capitalist economy than China's political elite. Last year, Premier Li Keqiang publicly acknowledged that 600-million Chinese people remain poor. Since Hu Jintao and Wen Jiaobao came to power in 2003, genuine efforts have been made to rebalance growth and reduce rural/urban inequalities after the early decades of reform saw a general collapse in rural welfare and unprecedented levels of social unrest. As part of efforts to modernize rural areas by building a "new socialist countryside," the Hu-Wen government abolished agricultural taxes, expanded health insurance, increased educational services for rural children and introduced new forms of social welfare targeted at alleviating poverty. Similar policies have continued in the era of Xi Jinping, as Beijing announced an end to "extreme poverty"last year. The relaxing of some hukou restrictions, the revival of the Mao-era slogan "common prosperity"and the announcement of China's new "principle contradiction"in 2017--"between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people's ever-growing needs for a better life"--must also be understood within this context.

Yet so too must China's approach to Covid-19. Beijing's capacity to mobilize the entire apparatus of the state to stamp out sporadic outbreaks is arguably the system's greatest strength. But as Chuan have brilliantly articulated, it also responds to a fundamental weakness. When the opinion pages of the Financial Times accuse Beijing of damaging international business by sticking to its zero-Covid strategy, they speak to and for global capitalist interests. Lacking sensitivity to the uneven nature of Chinese development, the potential human catastrophe that Chinese researchers warn of does not feature in their calculations. To combat such hubris, the left must remain sensitive to the distortions and injustices of forty years of reform. This is not to deny the country's remarkable socio-economic achievements. But for millions of Chinese people still struggling to live a decent life, it is to say that if livelihoods are to continue improving, it will be because of, not in spite of, Beijing's relentless effort to eliminate infections whenever and wherever they arise.

As the new Omicron variant of Covid-19 threatens to eviscerate the false sense of security that political elites in many rich countries have felt since vaccines were rolled out at the beginning of the year, critics of China's zero-Covid strategy may want to carefully reflect on why they have been so quick to dismiss Beijing's stringent containment measures.

Covid-19 has always been more than a public health crisis. It is an economic and political crisis; an environmental and social crisis; a crisis of information and a crisis of trust.

An opinion piece published in the Financial Times earlier this month took aim at Beijing's approach to stamping out the virus, calling it a "global concern." At the end of October, the New York Times published an article warning China's zero-Covid strategy risks isolating the country, both diplomatically and economically. Around the same time, the Guardian published a similar story while CNN also reported on how China is being left behind as its regional neighbors "learn to live" with the virus. Similar sentiments have been echoed across the corporate media, from Time and the Washington Post to the Economist and ABC.

Many of these reports share the assumption that we've already seen the worst of the pandemic, and that Beijing's strong-arm approach to governance means it is unable to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances. But this is way off the mark. Covid-19 has always been more than a public health crisis. It is an economic and political crisis; an environmental and social crisis; a crisis of information and a crisis of trust. In other words, it is a crisis that goes to the heart of the global system, holding up a mirror to individual societies and peeling away all the old pretenses. Big Pharma's monopoly on vaccines mean the risk of new variants emerging and causing havoc could continue well into the future, according to the WHO, as an intellectual property regime backed by the likes of the UK and Germany perpetuates structural health inequalities rooted in much longer histories of imperialism and dependency. Economic inequalities mean shutdowns of the type favored by European governments have always been a pipe dream in the underdeveloped world, where restrictions on work and travel have proven especially deadly. The wealth of the super-rich has spiked since the beginning of the pandemic, but hundreds of millions across the world have been plunged into new and dangerous forms of poverty, overturning even the most basic and rudimentary gains in global development. Such precarity can only increase desperation, pushing vulnerable individuals and groups back into work even as the virus mutates and takes on potentially more dangerous forms.

Instead of being viewed as an inefficient outcome of authoritarian rule, perhaps China's zero-Covid strategy should then be seen for what it is: a highly effective, if often ham-fisted, response to what so far is the biggest global crisis of the 21st-century. New research by mathematicians at Peking University warns a loosening of restrictions in China could unleash upwards of 600,000 infections a day, overloading the healthcare system. Earlier this month, Zhong Nanshan, the country's leading respiratory disease expert, warned of the costs of ending its zero-Covid policy. Gao Fu, the head of the Chinese CDC, has also called for the strategy to be maintained. When the highly popular virologist Zhang Wenhong suggested China needs to learn to "live with the virus" back in August, the state-media backlash reflected not only the depth of feeling within the Chinese leadership but also very real insecurities about the potentially catastrophic consequences of adopting alternative approaches to epidemic control.

What many of the critics of Beijing's zero-Covid strategy ignore are the tremendous regional and urban/rural inequalities that structure reform-era Chinese society. Simplistic narratives of the country's historic rise have been internalized both inside and outside the country, reflected across political divides in the West: the right pushing "China threat" narratives, as certain segments of the left fantasize about how China's growing superpower status promises a better future for all. The glittering skylines of Beijing, Shenzhen and Shanghai tend to muddle and confuse, proving effective antidotes at concealing the country's stark socio-economic differences. While the urban middle-class in coastal centers have access to genuinely world-class hospitals, villagers are sometimes denied even rudimentary healthcare. Many rural migrants go without due to a hukou system that reduces hundreds of millions to effective second-class citizenship in the places they live and work. In a study of nearly 350 cities conducted last year, researchers found 98 had no top-class hospitals, whereas 93 had only one. In comparison, Beijing and Guangzhou each had more than 50. Scrape beneath the surface still, and the numbers are even more staggering. A report by the WHO from a few years ago shows how China's public health spending per capita was around half that of Algeria and Brazil and nearly one-third that of Panama, with the figures starker still when compared to those of advanced economies.

When the opinion pages of the Financial Times accuse Beijing of damaging international business by sticking to its zero-Covid strategy, they speak to and for global capitalist interests.

Few are more aware of the tremendous dislocations and inequities in China's domestic economy caused by four-decades of integrating into the global capitalist economy than China's political elite. Last year, Premier Li Keqiang publicly acknowledged that 600-million Chinese people remain poor. Since Hu Jintao and Wen Jiaobao came to power in 2003, genuine efforts have been made to rebalance growth and reduce rural/urban inequalities after the early decades of reform saw a general collapse in rural welfare and unprecedented levels of social unrest. As part of efforts to modernize rural areas by building a "new socialist countryside," the Hu-Wen government abolished agricultural taxes, expanded health insurance, increased educational services for rural children and introduced new forms of social welfare targeted at alleviating poverty. Similar policies have continued in the era of Xi Jinping, as Beijing announced an end to "extreme poverty"last year. The relaxing of some hukou restrictions, the revival of the Mao-era slogan "common prosperity"and the announcement of China's new "principle contradiction"in 2017--"between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people's ever-growing needs for a better life"--must also be understood within this context.

Yet so too must China's approach to Covid-19. Beijing's capacity to mobilize the entire apparatus of the state to stamp out sporadic outbreaks is arguably the system's greatest strength. But as Chuan have brilliantly articulated, it also responds to a fundamental weakness. When the opinion pages of the Financial Times accuse Beijing of damaging international business by sticking to its zero-Covid strategy, they speak to and for global capitalist interests. Lacking sensitivity to the uneven nature of Chinese development, the potential human catastrophe that Chinese researchers warn of does not feature in their calculations. To combat such hubris, the left must remain sensitive to the distortions and injustices of forty years of reform. This is not to deny the country's remarkable socio-economic achievements. But for millions of Chinese people still struggling to live a decent life, it is to say that if livelihoods are to continue improving, it will be because of, not in spite of, Beijing's relentless effort to eliminate infections whenever and wherever they arise.