SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

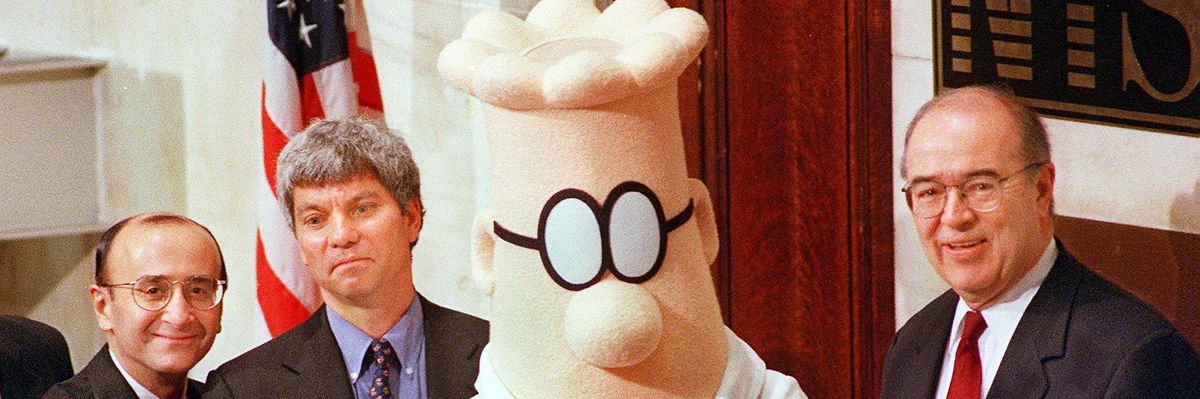

Dilbert, the comic strip character struggling to make his way up the corporate ladder, is joined by William Burleigh (R), President and Chief Executive Officer of the E.W. Scripps Company, Douglas Stern (2nd from L), Pres. and CEO of United Media, and Richard Grasso (L), Chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, to ring the opening bell as part of the activities to promote the launch of Dilbert's new television show on January 25, 1999. (Photo: Henny Ray Abrams/AFP via Getty Images)

To the delight of some and the dismay of others, the socialist idea continues to slowly, if very belatedly, make its way throughout the channels of American culture. Of particular recent note was its appearance in Dilbert, the daily comic strip send-up of the foibles of corporate office life. Of course, since it is the office's peripatetic do-nothing Wally who has experienced a socialist awakening, we get the lazy man's take on the subject. Still, the simple fact of "socialism" making it to the "funny pages" of the nation's remaining newspapers--has to qualify as some kind of news in itself.

They're finding that young voters associate socialism with words like workers, public, equal, and fair, while they link capitalism with terms such as exploitative, unfair, and the rich.

While the strip does hold great appeal for some critics of capitalism, few would look for political guidance from its creator, Scott Adams, who once announced a (temporary) switch in support from Donald Trump to Hillary Clinton because, "Where I live, in California, it is not safe to be seen as supportive of anything Trump says or does." But he certainly broke new ground when Wally one day announced, "I decided to become more of a socialist." The strip's coffee drinking shirker went on to explain to co-worker Alice that his conversion meant that, "With any luck, I'll benefit from your hard work without adding any value myself." When she replies that his viewpoint "feels immoral," Wally advises her to "Get back to work," because "I have bills to pay.

The political intervention would prove brief. The next day, Wally tells Dilbert that, "As a newly minted socialist, I look down on your capitalist ways," and asks him, "Why can't you be more generous and caring, like me?" to which the busy-at-work Dilbert replies, "Shouldn't you be working?" With this, Wally raises his ever present coffee mug and closes the second, and thus far final day of this excursion into political economy, replying that "It's optional under my system."

The mug-is-half -full take on all this might be to greet this casual humorous reference as a modest benchmark of socialism's increased acceptance in mainstream culture; the half-empty view might be to dismiss it as just another distorted, belittling reference. Either way, there's probably little point in over thinking the significance of a few panels in a comic strip. Perhaps more relevant, though, is the degree to which Dilbert's treatment wasn't notably less sophisticated than what else you'll encounter in American mass media--including in the ostensibly serious news.

There, the range of opinion on socialism generally runs from those who don't want to see socialism here, like President Joe Biden saying that "Communism is a failed system, a universally failed system. And I don't see socialism as a very useful substitute," to those who think it actually arrived here some time ago, like Alabama Republican Rep. Mo Brooks responding to a bomb threat evacuating several Capitol Hill buildings by empathizing with "citizenry anger directed at dictatorial Socialism."

And no disrespect to Scott Adams's work intended, but the fact is that some of what these real life guys have to say on the topic is way funnier than anything in Dilbert. High on this year's you-can't-make-this-stuff-up list of commenters on socialism had to be NY Rep. Elise Stefanik. Stefanik, who recently replaced Liz Chaney as third-ranking House Republican, greeted July 30th's 50-year anniversary of Medicare and Medicaid with a tweet celebrating "the critical role these programs have played to protect the healthcare of millions of families," while warning that "to safeguard our future, we must reject Socialist healthcare schemes."

Of course, anyone who knows anything about American history--which perhaps unfairly excludes Stefanik--knows that, at the time, her Republican forbears widely and famously denounced these very programs as another step down the slippery slope toward--yes--socialism. And "Not only socialism," warned then-Nebraska Sen. Carl Curtis, "it is brazen socialism." The prior year's Republican presidential candidate, Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, had already warned where this sort of thing could go if left unchecked: "Having given our pensioners their medical care in kind," he asked, "why not food baskets, why not public housing accommodations, why not vacation resorts, why not a ration of cigarettes for those who smoke and of beer for those who drink?" (Which, other than the cigarettes, does sound like a far better government spending program than the then-ongoing Vietnam war and the still-ongoing Middle East wars that have subsequently sucked up so much of the nation's resources.)

But again in the interest of fairness, it must be noted that the ranks of those appearing to be unclear on the concept is not confined to the political right. We have the example of New York Times columnist Paul Krugman taking Bernie Sanders to task during his 2020 presidential campaign for claiming that he was a socialist--when he actually wasn't! To quote: "Bernie Sanders isn't actually a socialist in any normal sense of the term" because he "doesn't want to nationalize our major industries and replace markets with central planning." (Krugman's consternation stemmed from the fact that Sanders was at the time the front-running presidential candidate and the Nobel Prize-winning economist feared that "his misleading self-description will be a gift to the Trump campaign.

Now, when Krugman consults his Webster's, that's no doubt pretty much the definition he finds. And you can find even stricter ones: Yahoo News has it that "In socialist economies, a central body--the government--owns and controls the society's assets, firms and resources, and distributes them to the population as it sees fit." But what's changed from these writers' school days is that the socialist idea has now actually entered into the flow of contemporary politics, in no small part due to Sanders's espousal of "democratic socialism" that resulted in millions of Americans hearing the idea pitched in their living rooms during the 2016 presidential debates--and a significant number of them liking it. And when an idea catches wind there will inevitably be a lot more opinions about what it means--and how to go about turning it into reality--than you're going to find in a dictionary entry.

If Krugman looked, he could no doubt find active socialist organizations that are generally in tune with the definitions he goes by. But a quick survey of politically active individuals favorably inclined toward the idea would likely show him a much broader range of thinking. Some might say that the move toward socialism they'd consider most necessary was the extension of our democratic rights into the workplace, combined with greater workers' control and/or ownership of corporations. Others would possibly focus their socialist vision more toward dramatically narrowing the nation's overall disparity in income and/or wealth. Still others might focus on broadly expanding the social services available to all--universal health insurance, a commitment to full employment, social housing, etc.

A common thread we would likely find coursing through all of their thinking, however, is a conviction that the current corporate-profit-driven economic system has not been, and will never be up to the twenty-first century challenge of maintaining the country and the planet in equitable and sustainable directions. That, along with a conviction that the present system must somehow be transcended. Such an overall diffusion of vision may be quite frustrating to the journalist seeking clear, crisp dictionary definitions before their deadline, but the fact is that when it comes to matters of politics, it those who do, who define.

For better or worse, much of this definition occurs in the mass media where even those favorably inclined often display a tendency to defensively bat questions on socialism back at questioners they consider adversarially inclined. The most familiar of this sort of response might be some variant of Dr. Martin Luther King's remark that the inequality of American society meant that, "We have socialism for the rich and rugged free-enterprise capitalism for the poor." Or maybe the internet meme, "Why, when Jesus talks about feeding the poor, it's Christianity but when a politician does it, it's Socialism?" Surprisingly, even President Harry S. Truman hit that note more than seventy-five years ago in response to critics of his proposal for universal health insurance: "Socialism is their name for almost anything that helps all the people."

Today, some might somewhat logically expect that, with a smattering of actually-existing socialist politicians now holding office, they will do the job for us. But really, even they can only do a small piece of what needs to be done. When Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, et al go about their legislative and advocacy business, their principal task will always be to attempt to nudge the American ship of state in a somewhat more just and democratic direction. They were not elected to be theorists; they were not elected primarily to paint a vision of the future. So far as their contribution to any discussions defining the long term meaning of socialism, their role mostly lies in setting an example, sort of "socialism is as socialists do." Which is to say, their proposals and their causes will be generally seen as pieces of an overall effort to equalize and democratize American society along the various lines described above.

The core of socialism is simply the extension of our political democracy into public control of the economy--by methods that may be appropriate to a set of varying, evolving circumstances.

The fact is, that for the rank and file socialist, in the end there ain't no one else going to do it for us. It's up to you and me to decide what it means to be a socialist in 21st century America and to define and fill in the visions of "socialism in its many shadings," as one writer has so well put it. And, frustrating as it may be to Doctor Krugman, much of this work will be a matter of nuance--of connotation, not denotation, if you will.

A recent U.K. survey of young voters (conducted by a right-wing think tank) concluded that "'Millennial Socialism' is not just a social media hype" and "not just a passing fad which ended with Jeremy Corbyn's resignation." (Corbyn is a British Labour Party leader who played a role somewhat similar to Sanders's.) The source of this pessimism on the right? Their finding that young voters associate socialism with words like workers, public, equal, and fair, while they link capitalism with terms such as exploitative, unfair, and the rich. Well, they got that right--and that half of the battle is every bit as important as having just the right socialism elevator pitch.

But before I get off the elevator, I should probably share my own personal shading, which is that the core of socialism is simply the extension of our political democracy into public control of the economy--by methods that may be appropriate to a set of varying, evolving circumstances. Nationalization, decentralized public control, workers control, worker ownership all may have their roles. And how will we know socialism when we see it? When it is no longer corporate capital primarily determining America's overall economic course, but democratically controlled institutions--with all the controversy that democracy can bring with it.

A final note. There are those who will say this is all well and good, but why risk misunderstanding by calling it "socialism"? Why not just promote universal health insurance, demilitarization of the economy, and all of the other things the political left generally advocates, without bringing in any bigger concepts? Why not take the Elizabeth Warren approach rather than the Bernie Sanders approach? I'll answer that question with a question: Which one started a movement? The democratic socialist or the one claiming to be capitalist to the bone? Vision matters.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

To the delight of some and the dismay of others, the socialist idea continues to slowly, if very belatedly, make its way throughout the channels of American culture. Of particular recent note was its appearance in Dilbert, the daily comic strip send-up of the foibles of corporate office life. Of course, since it is the office's peripatetic do-nothing Wally who has experienced a socialist awakening, we get the lazy man's take on the subject. Still, the simple fact of "socialism" making it to the "funny pages" of the nation's remaining newspapers--has to qualify as some kind of news in itself.

They're finding that young voters associate socialism with words like workers, public, equal, and fair, while they link capitalism with terms such as exploitative, unfair, and the rich.

While the strip does hold great appeal for some critics of capitalism, few would look for political guidance from its creator, Scott Adams, who once announced a (temporary) switch in support from Donald Trump to Hillary Clinton because, "Where I live, in California, it is not safe to be seen as supportive of anything Trump says or does." But he certainly broke new ground when Wally one day announced, "I decided to become more of a socialist." The strip's coffee drinking shirker went on to explain to co-worker Alice that his conversion meant that, "With any luck, I'll benefit from your hard work without adding any value myself." When she replies that his viewpoint "feels immoral," Wally advises her to "Get back to work," because "I have bills to pay.

The political intervention would prove brief. The next day, Wally tells Dilbert that, "As a newly minted socialist, I look down on your capitalist ways," and asks him, "Why can't you be more generous and caring, like me?" to which the busy-at-work Dilbert replies, "Shouldn't you be working?" With this, Wally raises his ever present coffee mug and closes the second, and thus far final day of this excursion into political economy, replying that "It's optional under my system."

The mug-is-half -full take on all this might be to greet this casual humorous reference as a modest benchmark of socialism's increased acceptance in mainstream culture; the half-empty view might be to dismiss it as just another distorted, belittling reference. Either way, there's probably little point in over thinking the significance of a few panels in a comic strip. Perhaps more relevant, though, is the degree to which Dilbert's treatment wasn't notably less sophisticated than what else you'll encounter in American mass media--including in the ostensibly serious news.

There, the range of opinion on socialism generally runs from those who don't want to see socialism here, like President Joe Biden saying that "Communism is a failed system, a universally failed system. And I don't see socialism as a very useful substitute," to those who think it actually arrived here some time ago, like Alabama Republican Rep. Mo Brooks responding to a bomb threat evacuating several Capitol Hill buildings by empathizing with "citizenry anger directed at dictatorial Socialism."

And no disrespect to Scott Adams's work intended, but the fact is that some of what these real life guys have to say on the topic is way funnier than anything in Dilbert. High on this year's you-can't-make-this-stuff-up list of commenters on socialism had to be NY Rep. Elise Stefanik. Stefanik, who recently replaced Liz Chaney as third-ranking House Republican, greeted July 30th's 50-year anniversary of Medicare and Medicaid with a tweet celebrating "the critical role these programs have played to protect the healthcare of millions of families," while warning that "to safeguard our future, we must reject Socialist healthcare schemes."

Of course, anyone who knows anything about American history--which perhaps unfairly excludes Stefanik--knows that, at the time, her Republican forbears widely and famously denounced these very programs as another step down the slippery slope toward--yes--socialism. And "Not only socialism," warned then-Nebraska Sen. Carl Curtis, "it is brazen socialism." The prior year's Republican presidential candidate, Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, had already warned where this sort of thing could go if left unchecked: "Having given our pensioners their medical care in kind," he asked, "why not food baskets, why not public housing accommodations, why not vacation resorts, why not a ration of cigarettes for those who smoke and of beer for those who drink?" (Which, other than the cigarettes, does sound like a far better government spending program than the then-ongoing Vietnam war and the still-ongoing Middle East wars that have subsequently sucked up so much of the nation's resources.)

But again in the interest of fairness, it must be noted that the ranks of those appearing to be unclear on the concept is not confined to the political right. We have the example of New York Times columnist Paul Krugman taking Bernie Sanders to task during his 2020 presidential campaign for claiming that he was a socialist--when he actually wasn't! To quote: "Bernie Sanders isn't actually a socialist in any normal sense of the term" because he "doesn't want to nationalize our major industries and replace markets with central planning." (Krugman's consternation stemmed from the fact that Sanders was at the time the front-running presidential candidate and the Nobel Prize-winning economist feared that "his misleading self-description will be a gift to the Trump campaign.

Now, when Krugman consults his Webster's, that's no doubt pretty much the definition he finds. And you can find even stricter ones: Yahoo News has it that "In socialist economies, a central body--the government--owns and controls the society's assets, firms and resources, and distributes them to the population as it sees fit." But what's changed from these writers' school days is that the socialist idea has now actually entered into the flow of contemporary politics, in no small part due to Sanders's espousal of "democratic socialism" that resulted in millions of Americans hearing the idea pitched in their living rooms during the 2016 presidential debates--and a significant number of them liking it. And when an idea catches wind there will inevitably be a lot more opinions about what it means--and how to go about turning it into reality--than you're going to find in a dictionary entry.

If Krugman looked, he could no doubt find active socialist organizations that are generally in tune with the definitions he goes by. But a quick survey of politically active individuals favorably inclined toward the idea would likely show him a much broader range of thinking. Some might say that the move toward socialism they'd consider most necessary was the extension of our democratic rights into the workplace, combined with greater workers' control and/or ownership of corporations. Others would possibly focus their socialist vision more toward dramatically narrowing the nation's overall disparity in income and/or wealth. Still others might focus on broadly expanding the social services available to all--universal health insurance, a commitment to full employment, social housing, etc.

A common thread we would likely find coursing through all of their thinking, however, is a conviction that the current corporate-profit-driven economic system has not been, and will never be up to the twenty-first century challenge of maintaining the country and the planet in equitable and sustainable directions. That, along with a conviction that the present system must somehow be transcended. Such an overall diffusion of vision may be quite frustrating to the journalist seeking clear, crisp dictionary definitions before their deadline, but the fact is that when it comes to matters of politics, it those who do, who define.

For better or worse, much of this definition occurs in the mass media where even those favorably inclined often display a tendency to defensively bat questions on socialism back at questioners they consider adversarially inclined. The most familiar of this sort of response might be some variant of Dr. Martin Luther King's remark that the inequality of American society meant that, "We have socialism for the rich and rugged free-enterprise capitalism for the poor." Or maybe the internet meme, "Why, when Jesus talks about feeding the poor, it's Christianity but when a politician does it, it's Socialism?" Surprisingly, even President Harry S. Truman hit that note more than seventy-five years ago in response to critics of his proposal for universal health insurance: "Socialism is their name for almost anything that helps all the people."

Today, some might somewhat logically expect that, with a smattering of actually-existing socialist politicians now holding office, they will do the job for us. But really, even they can only do a small piece of what needs to be done. When Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, et al go about their legislative and advocacy business, their principal task will always be to attempt to nudge the American ship of state in a somewhat more just and democratic direction. They were not elected to be theorists; they were not elected primarily to paint a vision of the future. So far as their contribution to any discussions defining the long term meaning of socialism, their role mostly lies in setting an example, sort of "socialism is as socialists do." Which is to say, their proposals and their causes will be generally seen as pieces of an overall effort to equalize and democratize American society along the various lines described above.

The core of socialism is simply the extension of our political democracy into public control of the economy--by methods that may be appropriate to a set of varying, evolving circumstances.

The fact is, that for the rank and file socialist, in the end there ain't no one else going to do it for us. It's up to you and me to decide what it means to be a socialist in 21st century America and to define and fill in the visions of "socialism in its many shadings," as one writer has so well put it. And, frustrating as it may be to Doctor Krugman, much of this work will be a matter of nuance--of connotation, not denotation, if you will.

A recent U.K. survey of young voters (conducted by a right-wing think tank) concluded that "'Millennial Socialism' is not just a social media hype" and "not just a passing fad which ended with Jeremy Corbyn's resignation." (Corbyn is a British Labour Party leader who played a role somewhat similar to Sanders's.) The source of this pessimism on the right? Their finding that young voters associate socialism with words like workers, public, equal, and fair, while they link capitalism with terms such as exploitative, unfair, and the rich. Well, they got that right--and that half of the battle is every bit as important as having just the right socialism elevator pitch.

But before I get off the elevator, I should probably share my own personal shading, which is that the core of socialism is simply the extension of our political democracy into public control of the economy--by methods that may be appropriate to a set of varying, evolving circumstances. Nationalization, decentralized public control, workers control, worker ownership all may have their roles. And how will we know socialism when we see it? When it is no longer corporate capital primarily determining America's overall economic course, but democratically controlled institutions--with all the controversy that democracy can bring with it.

A final note. There are those who will say this is all well and good, but why risk misunderstanding by calling it "socialism"? Why not just promote universal health insurance, demilitarization of the economy, and all of the other things the political left generally advocates, without bringing in any bigger concepts? Why not take the Elizabeth Warren approach rather than the Bernie Sanders approach? I'll answer that question with a question: Which one started a movement? The democratic socialist or the one claiming to be capitalist to the bone? Vision matters.

To the delight of some and the dismay of others, the socialist idea continues to slowly, if very belatedly, make its way throughout the channels of American culture. Of particular recent note was its appearance in Dilbert, the daily comic strip send-up of the foibles of corporate office life. Of course, since it is the office's peripatetic do-nothing Wally who has experienced a socialist awakening, we get the lazy man's take on the subject. Still, the simple fact of "socialism" making it to the "funny pages" of the nation's remaining newspapers--has to qualify as some kind of news in itself.

They're finding that young voters associate socialism with words like workers, public, equal, and fair, while they link capitalism with terms such as exploitative, unfair, and the rich.

While the strip does hold great appeal for some critics of capitalism, few would look for political guidance from its creator, Scott Adams, who once announced a (temporary) switch in support from Donald Trump to Hillary Clinton because, "Where I live, in California, it is not safe to be seen as supportive of anything Trump says or does." But he certainly broke new ground when Wally one day announced, "I decided to become more of a socialist." The strip's coffee drinking shirker went on to explain to co-worker Alice that his conversion meant that, "With any luck, I'll benefit from your hard work without adding any value myself." When she replies that his viewpoint "feels immoral," Wally advises her to "Get back to work," because "I have bills to pay.

The political intervention would prove brief. The next day, Wally tells Dilbert that, "As a newly minted socialist, I look down on your capitalist ways," and asks him, "Why can't you be more generous and caring, like me?" to which the busy-at-work Dilbert replies, "Shouldn't you be working?" With this, Wally raises his ever present coffee mug and closes the second, and thus far final day of this excursion into political economy, replying that "It's optional under my system."

The mug-is-half -full take on all this might be to greet this casual humorous reference as a modest benchmark of socialism's increased acceptance in mainstream culture; the half-empty view might be to dismiss it as just another distorted, belittling reference. Either way, there's probably little point in over thinking the significance of a few panels in a comic strip. Perhaps more relevant, though, is the degree to which Dilbert's treatment wasn't notably less sophisticated than what else you'll encounter in American mass media--including in the ostensibly serious news.

There, the range of opinion on socialism generally runs from those who don't want to see socialism here, like President Joe Biden saying that "Communism is a failed system, a universally failed system. And I don't see socialism as a very useful substitute," to those who think it actually arrived here some time ago, like Alabama Republican Rep. Mo Brooks responding to a bomb threat evacuating several Capitol Hill buildings by empathizing with "citizenry anger directed at dictatorial Socialism."

And no disrespect to Scott Adams's work intended, but the fact is that some of what these real life guys have to say on the topic is way funnier than anything in Dilbert. High on this year's you-can't-make-this-stuff-up list of commenters on socialism had to be NY Rep. Elise Stefanik. Stefanik, who recently replaced Liz Chaney as third-ranking House Republican, greeted July 30th's 50-year anniversary of Medicare and Medicaid with a tweet celebrating "the critical role these programs have played to protect the healthcare of millions of families," while warning that "to safeguard our future, we must reject Socialist healthcare schemes."

Of course, anyone who knows anything about American history--which perhaps unfairly excludes Stefanik--knows that, at the time, her Republican forbears widely and famously denounced these very programs as another step down the slippery slope toward--yes--socialism. And "Not only socialism," warned then-Nebraska Sen. Carl Curtis, "it is brazen socialism." The prior year's Republican presidential candidate, Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, had already warned where this sort of thing could go if left unchecked: "Having given our pensioners their medical care in kind," he asked, "why not food baskets, why not public housing accommodations, why not vacation resorts, why not a ration of cigarettes for those who smoke and of beer for those who drink?" (Which, other than the cigarettes, does sound like a far better government spending program than the then-ongoing Vietnam war and the still-ongoing Middle East wars that have subsequently sucked up so much of the nation's resources.)

But again in the interest of fairness, it must be noted that the ranks of those appearing to be unclear on the concept is not confined to the political right. We have the example of New York Times columnist Paul Krugman taking Bernie Sanders to task during his 2020 presidential campaign for claiming that he was a socialist--when he actually wasn't! To quote: "Bernie Sanders isn't actually a socialist in any normal sense of the term" because he "doesn't want to nationalize our major industries and replace markets with central planning." (Krugman's consternation stemmed from the fact that Sanders was at the time the front-running presidential candidate and the Nobel Prize-winning economist feared that "his misleading self-description will be a gift to the Trump campaign.

Now, when Krugman consults his Webster's, that's no doubt pretty much the definition he finds. And you can find even stricter ones: Yahoo News has it that "In socialist economies, a central body--the government--owns and controls the society's assets, firms and resources, and distributes them to the population as it sees fit." But what's changed from these writers' school days is that the socialist idea has now actually entered into the flow of contemporary politics, in no small part due to Sanders's espousal of "democratic socialism" that resulted in millions of Americans hearing the idea pitched in their living rooms during the 2016 presidential debates--and a significant number of them liking it. And when an idea catches wind there will inevitably be a lot more opinions about what it means--and how to go about turning it into reality--than you're going to find in a dictionary entry.

If Krugman looked, he could no doubt find active socialist organizations that are generally in tune with the definitions he goes by. But a quick survey of politically active individuals favorably inclined toward the idea would likely show him a much broader range of thinking. Some might say that the move toward socialism they'd consider most necessary was the extension of our democratic rights into the workplace, combined with greater workers' control and/or ownership of corporations. Others would possibly focus their socialist vision more toward dramatically narrowing the nation's overall disparity in income and/or wealth. Still others might focus on broadly expanding the social services available to all--universal health insurance, a commitment to full employment, social housing, etc.

A common thread we would likely find coursing through all of their thinking, however, is a conviction that the current corporate-profit-driven economic system has not been, and will never be up to the twenty-first century challenge of maintaining the country and the planet in equitable and sustainable directions. That, along with a conviction that the present system must somehow be transcended. Such an overall diffusion of vision may be quite frustrating to the journalist seeking clear, crisp dictionary definitions before their deadline, but the fact is that when it comes to matters of politics, it those who do, who define.

For better or worse, much of this definition occurs in the mass media where even those favorably inclined often display a tendency to defensively bat questions on socialism back at questioners they consider adversarially inclined. The most familiar of this sort of response might be some variant of Dr. Martin Luther King's remark that the inequality of American society meant that, "We have socialism for the rich and rugged free-enterprise capitalism for the poor." Or maybe the internet meme, "Why, when Jesus talks about feeding the poor, it's Christianity but when a politician does it, it's Socialism?" Surprisingly, even President Harry S. Truman hit that note more than seventy-five years ago in response to critics of his proposal for universal health insurance: "Socialism is their name for almost anything that helps all the people."

Today, some might somewhat logically expect that, with a smattering of actually-existing socialist politicians now holding office, they will do the job for us. But really, even they can only do a small piece of what needs to be done. When Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, et al go about their legislative and advocacy business, their principal task will always be to attempt to nudge the American ship of state in a somewhat more just and democratic direction. They were not elected to be theorists; they were not elected primarily to paint a vision of the future. So far as their contribution to any discussions defining the long term meaning of socialism, their role mostly lies in setting an example, sort of "socialism is as socialists do." Which is to say, their proposals and their causes will be generally seen as pieces of an overall effort to equalize and democratize American society along the various lines described above.

The core of socialism is simply the extension of our political democracy into public control of the economy--by methods that may be appropriate to a set of varying, evolving circumstances.

The fact is, that for the rank and file socialist, in the end there ain't no one else going to do it for us. It's up to you and me to decide what it means to be a socialist in 21st century America and to define and fill in the visions of "socialism in its many shadings," as one writer has so well put it. And, frustrating as it may be to Doctor Krugman, much of this work will be a matter of nuance--of connotation, not denotation, if you will.

A recent U.K. survey of young voters (conducted by a right-wing think tank) concluded that "'Millennial Socialism' is not just a social media hype" and "not just a passing fad which ended with Jeremy Corbyn's resignation." (Corbyn is a British Labour Party leader who played a role somewhat similar to Sanders's.) The source of this pessimism on the right? Their finding that young voters associate socialism with words like workers, public, equal, and fair, while they link capitalism with terms such as exploitative, unfair, and the rich. Well, they got that right--and that half of the battle is every bit as important as having just the right socialism elevator pitch.

But before I get off the elevator, I should probably share my own personal shading, which is that the core of socialism is simply the extension of our political democracy into public control of the economy--by methods that may be appropriate to a set of varying, evolving circumstances. Nationalization, decentralized public control, workers control, worker ownership all may have their roles. And how will we know socialism when we see it? When it is no longer corporate capital primarily determining America's overall economic course, but democratically controlled institutions--with all the controversy that democracy can bring with it.

A final note. There are those who will say this is all well and good, but why risk misunderstanding by calling it "socialism"? Why not just promote universal health insurance, demilitarization of the economy, and all of the other things the political left generally advocates, without bringing in any bigger concepts? Why not take the Elizabeth Warren approach rather than the Bernie Sanders approach? I'll answer that question with a question: Which one started a movement? The democratic socialist or the one claiming to be capitalist to the bone? Vision matters.