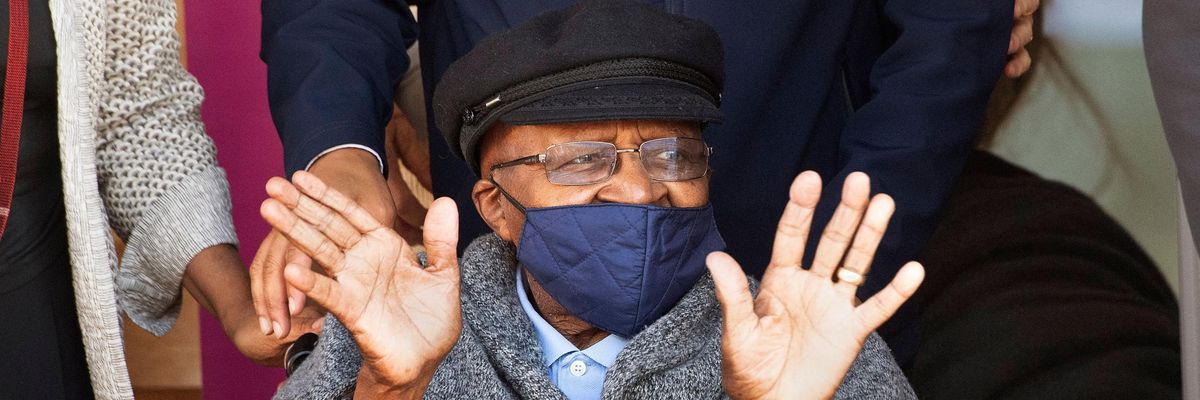

Archbishop Desmond Tutu died the day after Christmas at the age of 90. The Nobel Peace laureate was a leader in the movement to overthrow apartheid, South Africa's brutal system of racial segregation. After that historic victory and the election of Nelson Mandela as South Africa's first Black president in 1994, Tutu led the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, pursuing restorative justice rather than retribution. After that, Tutu continued demonstrating and speaking out around the world for justice, peace, women's equality, gay rights, in solidarity with Palestinians, and more.

Tutu continued demonstrating and speaking out around the world for justice, peace, women's equality, gay rights, in solidarity with Palestinians, and more.

Born in South Africa in 1931, Tutu grew up under racist laws imposed over centuries of colonialism. In 1948, the hardline white supremacist National Party swept the elections and instituted apartheid. As a college student in the early 1950s, Tutu met Nelson Mandela. They wouldn't meet again for close to 40 years, until after Mandela served 27 years in prison.

Tutu became an Anglican priest, and rapidly rose in the clergy. He took charge of the South African Council of Churches, transforming it into a major human rights organization. He mobilized domestic and international opposition to apartheid, including an international economic boycott of South Africa.

Testifying before the U.S. Congress in 1984, Tutu denounced the Reagan administration:

"Apartheid is as evil, as immoral, as un-Christian, in my view, as Nazism. And in my view, the Reagan administration's support and collaboration with it is equally immoral, evil and totally un-Christian."

Later that year he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

"Governments don't always represent their people," Tutu said at the 2001 World Conference against Racism in Durban, South Africa, reflecting on the importance of grassroots action in the United States in overcoming Reagan's support for the apartheid regime. "We tried to persuade the Reagan White House to impose sanctions against South Africa. And the Reagan White House was firmly set against that. We appealed over their heads, to the people. And they were fantastic. The response was that the moral climate in the United States changed. And they did not just pass the anti-apartheid legislation, they mustered a presidential veto override."

Tutu was referring to Reagan's veto of The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, which had passed both houses of Congress with overwhelming support. The Republican-controlled Senate overrode Reagan's veto by a vote of 78-21.

"Apartheid's rulers bit the dust, as all oppressors have done always, for this is a moral universe," Tutu said in 2007 in a speech at Boston's Old South Church. "Right and wrong matter. It cannot happen that evil, injustice and oppression can have the last word. No, ultimately goodness, justice, freedom--these will prevail."

Archbishop Tutu gave the Boston speech not long after St. Thomas University in Minneapolis/St. Paul rescinded an invitation to speak because of his unwavering solidarity with Palestinians. Facing a public backlash, the Catholic university then reversed its own decision and issued Tutu an apology and a re-invitation. He elaborated on Israel/Palestine in 2008, appearing on the Democracy Now! news hour. He described a visit to the region, during which Israel prevented him from entering Gaza:

"For me, coming from South Africa and looking at the checkpoints and the arrogance of those young soldiers--it reminds me of the kind of experiences that we underwent. I was Bishop of Johannesburg and would be driving with my wife from town to Soweto, where we lived, and we'd have a roadblock, and the fact of our having to have passes allowing us to move freely in the land of our birth. And now you have that extraordinary structure--the wall."

Tutu "selflessly fought the evils of racism during the most terrible days of apartheid," Nelson Mandela wrote of Desmond Tutu in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom. Mandela went on, describing their reunion following his release from prison: "When I greeted Archbishop Tutu, I enveloped him in a great hug; here was a man who inspired an entire nation with his words and his courage, who had revived the people's hope during the darkest of times."

We find ourselves again in dark times, with authoritarianism on the rise, widening economic inequality, vaccine apartheid in the midst of a pandemic and the worsening climate emergency. Speaking to youth activists outside the United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen, Denmark in 2009, Tutu said, "For those who think that the rich are going to escape--hahaha!--we either swim or sink together." Unleashing his signature squeal of laughter, Tutu's principled resistance was suffused with expressions of joy and compassion. "We have one world, and we want to leave a beautiful world for this beautiful, wonderful young generation. We, the oldies, want to leave you a beautiful world. It is a matter of morality. It is a question of justice."